Unit ~'India:Physical Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bharati Volume 4

SARASVATI Bharati Volume 4 Gold bead; Early Dynastic necklace from the Royal Cemetery; now in the Leeds collection y #/me raed?sI %/-e A/hm! #N/m! Atu?vm! , iv/Èaim?Sy r]it/ e/dm! -ar?t jn?m! . (Vis'va_mitra Ga_thina) RV 3.053.12 I have made Indra glorified by these two, heaven and earth, and this prayer of Vis'va_mitra protects the race of Bharata. [Made Indra glorified: indram atus.t.avam-- the verb is the third preterite of the casual, I have caused to be praised; it may mean: I praise Indra, abiding between heaven and earth, i.e. in va_kdevi Sarasvati the firmament]. Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Babasaheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti Bangalore 2003 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com SARASVATI: Bharati by S. Kalyanaraman Copyright Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Publisher: Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Bangalore Price: (India) Rs. 500 ; (Other countries) US $50 . Copies can be obtained from: S. Kalyanaraman, 3 Temple Avenue, Srinagar Colony, Chennai, Tamilnadu 600015, India email: [email protected] Tel. + 91 44 22350557; Fax 24996380 Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Yadava Smriti, 55 First Main Road, Seshadripuram, Bangalore 560020, India Tel. + 91 80 6655238 Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, Annapurna, 528 C Saniwar Peth, Pune 411030 Tel. +91 020 4490939 Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Kalyanaraman, Srinivasan. Sarasvati/ S. Kalyanaraman Includes bibliographical references and index 1.River Sarasvati. 2. Indian Civilization. 3. R.gveda Printed in India at K. Joshi and Co., 1745/2 Sadashivpeth, Near Bikardas Maruti Temple, Pune 411030, Bharat ISBN 81-901126-4-0 FIRST PUBLISHED: 2003 2 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com About the Author Dr. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

The Vakatakas

CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS or THE VAKATAKAS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS OF THE VAKATAKAS EDITED BY Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, M.A., D.Litt* Hony Piofessor of Ancient Indian History & Culture University of Nagpur GOVERNMENT EPIGRAPHIST FOR INDIA OOTACAMUND 1963 Price: Rs. 40-00 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA PLATES PWNTED By THE MRECTOR; LETTERPRESS P WNTED AT THE JQB PREFACE after the of the publication Inscriptions of the Kalachun-Chedi Era (Corpus Inscrip- tionum Vol in I SOON Indicarum, IV) 1955, thought of preparing a corpus of the inscriptions of the Vakatakas for the Vakataka was the most in , dynasty glorious one the ancient history of where I the best Vidarbha, have spent part of my life, and I had already edited or re-edited more than half the its number of records I soon completed the work and was thinking of it getting published, when Shri A Ghosh, Director General of Archaeology, who then happened to be in Nagpur, came to know of it He offered to publish it as Volume V of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Series I was veiy glad to avail myself of the offer and submitted to the work the Archaeological Department in 1957 It was soon approved. The order for it was to the Press Ltd on the printing given Job (Private) , Kanpur, 7th 1958 to various July, Owing difficulties, the work of printing went on very slowly I am glad to find that it is now nearing completion the course of this I During work have received help from several persons, for which I have to record here my grateful thanks For the chapter on Architecture, Sculpture and I found Painting G Yazdam's Ajanta very useful I am grateful to the Department of of Archaeology, Government Andhra Pradesh, for permission to reproduce some plates from that work Dr B Ch Chhabra, Joint Director General of Archaeology, went through and my typescript made some important suggestions The Government Epigraphist for India rendered the necessary help in the preparation of the Skeleton Plates Shri V P. -

An Epigraphical Study

urushottama - Jagannath, the Lord of the period, when god Vishnu was conceived as a Universe, the supreme god has been member of the solar family. Pworshipped in various names / forms, from In Odisha the earliest epigraphic time to time with different mode of doctrine and evidences of Vaishnavism is traced in copper plate rituals. The literary and epigraphic sources throw records of Mathara dynasty who ruled over considerable light on the origin of this cult. Kalinga about 4th/5th century A.D. shortly after The religious life of Odisha has been the Samudragupta military expedition to south. dominated by the Cult of Purushottama - The Mathara established independent rule over Jagannath. The Jagannath is regarded as Daru Kalinga, during their rule Vaishnavism advanced Brahma. Among the many rituals of the god, into Kalinga where it enjoyed royal patronage. Nabakalebara is one of the important ceremonies, The Ningondi grant of Prabhanjanavarman which involves a total replacement of the deities mentioned that he was the devout worshipper at through the new ones. The supreme god of the the feet of Bhagavat Narayanasvami. Similarly in Puri is originally a tribal deity. The different rituals the Andhavaram grant of Anantasaktivarman, who is described as the Lord of Kalinga and a devout Nabakalebara and the Evolution of Purushottama Cult : An Epigraphical Study Dr. Bharati Pal of the Nabakalebara ceremony are the finest worshipper at the feet of god Narayana whose examples of the superimposition of the chest was embraced kamala nilaya Lakshmi. Brahmanism Hinduism on a cult which was purely Again Chandavarman and Nandaprabhan- tribal origin. -

Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early Time to 8Th-12Th Century C.E)

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper-XII Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early time to 8th-12th Century C.E) By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 CONTENT SOCIO- POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF ANCIENT INDIA (EARLY TIME TO 8th-12th CENTURIES C.E) Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Political Condition. 1. The emergence of Rajput: Pratiharas, Art and Architecture. 02-14 2. The Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta: Their role in history, 15-27 Contribution to art and culture. 3. The Pala of Bengal- Polity, Economy and Social conditions. 28-47 Unit-II Other political dynasties of early medieval India. 1. The Somavamsis of Odisha. 48-64 2. Cholas Empire: Local Self Government, Art and Architecture. 65-82 3. Features of Indian Village System, Society, Economy, Art and 83-99 learning in South India. Unit-III. Indian Society in early Medieval Age. 1. Social stratification: Proliferation of castes, Status of women, 100-112 Matrilineal System, Aryanisation of hinterland region. 2. Religion-Bhakti Movements, Saivism, Vaishnavism, Tantricism, 113-128 Islam. 3. Development of Art and Architecture: Evolution of Temple Architecture- Major regional Schools, Sculpture, Bronzes and 129-145 Paintings. Unit-IV. Indian Economy in early medieval age. 1. General review of the economic life: Agrarian and Urban 146-161 Economy. 2. Indian Feudalism: Characteristic, Nature and features. 162-180 Significance. 3. Trade and commerce- Maritime Activities, Spread of Indian 181-199 Culture abroad, Cultural Interaction. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is pleasure to be able to complete this compilation work. containing various aspects of Ancient Indian History. This material is prepared with an objective to familiarize the students of M.A History, DDCE Utkal University on the various aspcets of India’s ancient past. -

The Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa

THE DESCRlPTrON OF JAMBTJ-DVIPA. 275 Canto LIV. The description of Jamhu-dvvpa, Mdrkandeya tells KraushtuM further the size of the earth, and irta order and dimensions of the seven continents and their oceans—He describes Jamhu-dvtpa, the countries in it, and Meru and the other mountains ; and mentions various local facts. Kraustuki spoke. 1 How many are the continents, and how many the oceans, and how many are' the mountains, O brahman ? And how many are the countries, and what are their rivers, Muni ? 2 And the size of the great objects of nature,* and the Lok^- loka mountain-range ; the circumference, and the size and 3 the course of the moon and the sun also—^tell me all this at length, great Muni. Markandeya spoke. 4 The earth is fifty times ten million yojanasf broad in every direction,^ O brahman. I tell thee of its entire consti- 5 tution, hearken thereto. The dvipas which I have mentioned to thee, began with Jambu-dvipa and ended with Pushkara- dvipa, illustrious brahman ; listen further to their dimen- 6 sions. Now each dvipa is twice the size of the dvipa which precedes it in this order, Jambu, and Plaksha, S^almala, Ku^a, 7 Kraunc'a and S'aka, and the Pushkara-dvipa, They are completely surrounded by oceans of salt water, sugar-cane juice, wine, ghee, curdled milk, and milk, which increase double and double, compared with each preceding one. 8 I will tell thee of the constitution of Jambu-dvfpa ; hearken to me. It is a hundred thousand yojanas in breadth and length, 9 it being of a circular shape. -

Geomorphic Conditions, Archaeological - Architectural Heritage Structures and Conservation of Ancient Hindu Malhar Mud Fort Chattisgarh, India

ISSN: 2455-2631 © July 2021 IJSDR | Volume 6 Issue 7 GEOLOGIC- GEOMORPHIC CONDITIONS, ARCHAEOLOGICAL - ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE STRUCTURES AND CONSERVATION OF ANCIENT HINDU MALHAR MUD FORT CHATTISGARH, INDIA Dr. HD.DIWAN*, Dr. S.S. BHADAURIA**, Dr. PRAVEEN KADWE***, Dr. D.SANYAL**** *Alumni, Department of Applied Geology, Deptt. Of Civil Engineering, NIT, Raipur, C.G., India **Head, Department of Geology, Govt. NPG College of Science Raipur, C.G. ***Head, Department of Defense Studies, Govt. NPG College of Science Raipur, C.G. ****Head, Department of Architecture, NIT, Raipur, C.G., India Abstract: The ancient trade route from Kausambi to the South - Eastern Sea Side i.e. Jagganath Puri, Odisha were followed via Bharhut, Bandhavgarh, Amarkantak of M.P. and Kharod, Malhar, Sirpur in C.G. The Malhar is located in Bilaspur district, CG towards South East, about 32 km. distance and lies in geographical Latitude North 21°55' and East longitude 82°20’ in Masturi Tahsil. Under Natural Heritages, the environment of Malhar is surrounded by three rivers, Arpa in the West, Lilagar in the East Shivnath in the South. The landscape shows undulating plains (250 m AMSL) with gentle slope towards lowlying, river drainage channels, due to presence of Sedimentary Horizontal Bedded (SHB) rock Formations of Chhattisgarh (Protereozoic) Supergroup. The excavations at Malhar by Archaealogical Survey of India (ASI) designated as ASI code - NCT - 17, and Archaeology Deptt. of C.G. State, considered continuous inhabitation, ancient civilization from Ancient period to Medieval period in Indian History. The ancient fort - Ramparts in Kosala Village and Ferry Potnar, still exists at present, indicates its antiquity to Pre-Mauryan reign period (600 BC). -

Myth of One Hindu Religion Exploded' by Hadwa Dom Was Published By

Myth of One Hindu Religion by Dr. Hadwa Dom `Myth of One Hindu Religion Exploded' by Hadwa Dom was published by Sudrastan Books, Jabalpur, 1999 free from Copyright. It was thence reprinted in Dalitstan Journal, Volume 1, Issue 2 (Oct. 1999) and has been archived in the Ambedkar Library. It is available for free public distribution as per the Ambedkar Library Public Licence: `You may freely distribute this work, as long as you do not make money from it and clearly state the internet location of Ambedkar Library, http://www.dalitstan.org/books/, where you obtained it.' Source: http://www.dalitstan.org/books/mohr/index.html Copied from: http://web.archive.org/web/20020417023203/www.dalitstan.org/books/ mohr/index.html 1 Chapter 1 Myth of One Hindu Religion Exploded by Hadwa Dom I was born and brought up in what would be termed a `semi-Hinduised' background in what is now south Bihar. My caste is that of the Doms, classified as a `Scheduled Caste' by the Indian Constitution. From my school days in my native Bihar I was taught that my religion was `Hinduism', and that all Indians, except for a few renegade Muslims, Christians and Sikhs, accepted without question the leadership of Brahmins and venerated the Vedas. That Rama was `our' god, who destroyed the `evil demon' Ravan, all our languages were merely `degraded forms' of Sanskrit, and `Indian is One Hindu Nation' came to be fundamental beliefs of mine. These were only some of the nice myths that the Brahmins and Aryan Vaishnavas, the followers of the 6 astika schools of Brahmanism, were telling us. -

A Short History of Creation

A HISTORY OF CREATION FOR THE FIRST TIME READER by N.KRISHNASWAMY LORD BRAHMA, THE CREATOR OF ALL CREATION A VIDYA VRIKSHAH PUBLICATION LIST OF CONTENTS Dedication & Acknowledgements Foreword Preface Chapter – 1 : Vyasa the Editor Chapter – 2 : Brahma the - Creator Chapter - 3 : Vishnu the Preserver Chapter – 4 : Shiva – The Transformer Chapter – 5 : Devi – The Mother Chapter – 6 : Puranjana – the Perfect Myth Chapter - 7 : Itihasa – I : Vedic Indian History Chapter - 8 : Itihasa – II : Vedic World History Chapter – 9 : Itihasa – III : Ramayana/Mahabharata Chapter – 10 : Itihasa – IV : Puranic Indian History Chapter – 11 : Itihasa – V : Modern Version of Puranic History Chapter – 12 : Whither History ? Annexure – 1 : The Time Scale of Creation Annexure – 2 : Puranic Geneology of Solar Dynasty Leading to Buddha of the Ikshvaku Dynasty Annexure – 3 : Paper published by Kota Venkatachelam Annexure – 4 : Ashoka’s Edicts : Some Intriguing Facts --------------------------------------- DEDICATION TO A VOICE OF TRUTH SHRI KOTA VENKATACHALAM taking the name Sri Avyananda Bharati Swamy after entering Sanyasa, and assuming the role of the Peethapati of the Sri Sri Abhinava Virupakha Peetham A MODERN SCHOLAR WHO FOLLOWED IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF OUR ANCIENT SAGES TO PRESERVE THE SANCTITY OF THE VEDAS AND PURANAS, PROTECT THE INTEGRITY OF INDIAN CULTURE AND ENSURE THAT INDIAN HISTORY SHALL REST ON TRUTH -------------------------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is published under the auspices of Vidya Vrikshah, Chennai, a no-profit social service organization devoted to the spread of literacy and education, covering ancient and modern knowledge, and specially serve the socially and physically disabled poor of India, specially the blind. This book, like all our other publications, is not priced and is available as an e-book for free download from its website www.vidyavrikshah.org. -

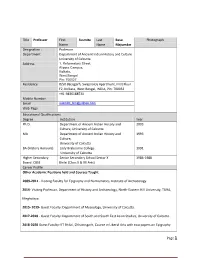

Page 1 Title Professor First Name Susmita Last Name Basu Majumdar Photograph Designation

Title Professor First Susmita Last Basu Photograph Name Name Majumdar Designation : Professor Department Department of Ancient Indian History and Culture University of Calcutta Address 1, Reformatory Street, Alipore Campus, Kolkata, West Bengal Pin: 700027 Residence 8/50 Bijoygarh, Swapnaloy Apartment, First Floor F2, Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA, Pin: 700032 +91-9836188531 Mobile Number Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. Department of Ancient Indian History and 2003 Culture, University of Calcutta MA Department of Ancient Indian History and 1993 Culture, University of Calcutta BA (History Honours) Lady Brabourne College 1991 University of Calcutta Higher Secondary Senior Secondary School Sector X 1986-1988 Board: CBSE Bhilai (Class X & XII Arts) Career Profile Other Academic Positions held and Courses Taught 2009-2011 - Visiting Faculty for Epigraphy and Numismatics, Institute of Archaeology. 2014- Visiting Professor, Department of History and Archaeology, North-Eastern Hill University, TURA, Meghalaya. 2015- 2019- Guest Faculty: Department of Museology, University of Calcutta. 2017-2018 - Guest Faculty: Department of South and South East Asian Studies, University of Calcutta. 2018-2020 Guest Faculty: IIT Bhilai, Chhattisgarh, Course in Liberal Arts with two papers on Epigraphy Page 1 and Numismatics and History Medicine and Surgery. Members of Prestigious Academic Institutions and Positions held 2018-2020: Member of the Executive Committee and General Committee of the Centre for -

Culture Heritage History and Historiography in Dandakaranya (BC to 1250AD)– Vol

DYNASTY HISTORY OF UNITED KORAPUT (B.C. to 1250AD) DAS KORNEL First published 2017 @ Das Kornel 2017 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. ISBN 978-93-5288-893-1 Published by Das Kornel, 2017 [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: +91 9437411576 Coverpage by Arjun Ojha Dedicated to Prof.N.K.Sahu, the eminent Historian of Odisha who contributed immensely to the knowledge of local History in Western Odisha and Emperor Kharavela Dr. Das Kornel Dr. Das Kornel was born in a Punjabi family at Jeypore (Koraput district) in Odisha State of India on 18th August 1948. His family came down during 1870 from Amritsar to Jeypore, then was under the Agency area of Visakahpatam in Madras Presidency and Jeypore as a State ruled by the Suryavamsi family; they have few documents since 1892. Dr.Kornel is a qualified Veterinarian with specialization in Animal Genetics and exercised his profession uptill 1999.He had an excellent accademic carrier and had earned Honours to his degree and 3 University Goldmedals and several prizes. He worked with Government of India in various positions since 1971 and took Voluntry retirement from the post of Director, CCBF in 1999.He was instrumental in establishing Indo-Australian Sheep Breeding Project, Hissar and Central Cattle (Jersey) Breeding Farm, Sunabeda, Government of India. He had established Frozen Semen Bank and Embryo Transfer Laboratory in CCBF, Sunabeda. He has worked with DANIDA as Danida Advisor for 10 long years and was the Programmee Coordinator (IC- SDC) Indo-Swiss Natural Resource Management Programme, Odisha for 4 years. -

Odradesa in the Inscriptions

Orissa Review * April - 2008 Odradesa in the Inscriptions Bharati Pal Orissa was famous as Kalinga, Kosala, Utkala As mentioned in the Pasupati inscription the and Odradesa during ancient days. This part of invasion of Odra along with Gauda by the country which at present is known to us as Harshavarman the king of Kamarupa, came as a Orissa, derive its name from Odra of ancient blessing for Odra. The conquest of Odra (Utkala) times.The great Sanskrit epics like the by the Assamese king resulted in the Mahabharata and Ramayan and Pali literature amalgamation of small kingdoms into a larger repeatedly mention Oddaka or Odra respectively, political unit and the destruction of warring tribes. while the Greeks speaks of Orates, which can be Odra and Utkala emerged as a full-fledged state equated with Sanskrit Odra. The Matsya Purana under the suzerainty of Harshavarman who speaks of the Odra as people inhabiting the probably appointed Kshemankara to rule over it Vindhyan mountain range. as his vassal. The earliest epigraphic evidence to The Pasupati Temple Inscription of Nepal Odradesa is found from the Soro copper plate describe that Jayadeva the king of Nepal married grant of Somadutta.The charter records the grant to Rajyamati who possessed virtues befitting her of a village called Adayara situated in Sareph- race, the noble descendant of Bhagadutta's royal ahara Vishaya in Uttar-Toshali which again line and daughter of Sri Harshavarman, lord of formed a part of the Odra Vishaya in favour of Gauda, Odra, Kalinga, Kosala and other land, Arungasvamin, Dhruvamitrasvamin and others of who crushed the heads of hostile kings with club the Vatsya gotra and the Vajasaneya Charana.