Aspirin and Ticlopidine for Prevention of Recurrent Stroke in Black Patients a Randomized Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticlopidine in Its Prodrug Form Is a Selective Inhibitor of Human Ntpdase1

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Mediators of Inflammation Volume 2014, Article ID 547480, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/547480 Research Article Ticlopidine in Its Prodrug Form Is a Selective Inhibitor of Human NTPDase1 Joanna Lecka,1,2 Michel Fausther,1,2 Beat Künzli,3 and Jean Sévigny1,2 1 Departement´ de Microbiologie-Infectiologie et d’Immunologie, FacultedeM´ edecine,´ UniversiteLaval,Qu´ ebec,´ QC, Canada G1V 0A6 2 Centre de Recherche du CHU de Quebec,´ 2705 Boulevard Laurier, Local T1-49, Quebec,´ QC, Canada G1V 4G2 3 Department of Surgery, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technische Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ 81675 Munich, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to Jean Sevigny;´ [email protected] Received 12 May 2014; Accepted 21 July 2014; Published 11 August 2014 Academic Editor: Mireia Mart´ın-Satue´ Copyright © 2014 Joanna Lecka et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (NTPDase1), like other ectonucleotidases, controls extracellular nucleotide levels and consequently their (patho)physiological responses such as in thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Selective NTPDase1 inhibitors would therefore be very useful. We previously observed that ticlopidine in its prodrug form, which does not affect P2 receptor activity, inhibited the recombinant form of human NTPDase1 ( =14M). Here we tested whether ticlopidine can be used as a selective inhibitor of NTPDase1. We confirmed that ticlopidine inhibits NTPDase1 in different forms and in different assays. The ADPase activity of intact HUVEC as well as of COS-7 cells transfected with human NTPDase1 was strongly inhibited by 100 M ticlopidine, 99 and 86%, respectively. -

Effects of Remote Ischemic Pre-Conditioning on Neurologic

Effects of Remote Ischemic Pre-Conditioning on Neurologic Complications in Adult Ischemic Moyamoya Disease Patients Undergoing Encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis(RIME) —— A Prospective, Multi-center, Randomized Controlled Trial —— Study Protocol Neurosurgical Principal Investigator Yuanli Zhao Professor of Neurosurgery Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Peking University International Hospital, Peking University, Beijing Rong Wang Professor of Neurosurgery Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Peking University International Hospital, Peking University, Beijing Xun Ye Professor of Neurosurgery Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Peking University International Hospital, Peking University, Beijing August 20, 2019 1. Protocol Synopsis Effects of Remote Ischemic Pre-Conditioning on Neurologic Complications in Adult Ischemic Moyamoya Title Disease Patients Undergoing Encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis Acronym RIME • To evaluate the safety of remote ischemic preconditioning in adult ischemic MMD patients undergoing indirect revascularization; Objectives • To evaluate the clinical benefit of remote ischemic preconditioning in adults with ischemic MMD who underwent indirect revascularization. This study was a multi-center, prospective, randomized, controlled trial of randomized (1:1) adult ischemic MMD patients undergoing indirect revascularization into two groups: 1. RIPC group Remote limb ischemic preconditioning (RIPC) is consisted of five 5-min cycles of bilateral arm -

Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Executive Agency for Health and Consumers Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play 24 January 2012 Final Report Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Acknowledgements Matrix Insight Ltd would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this research. We are especially grateful to the following institutions for their support throughout the study: the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) including their national member associations in Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland and the United Kingdom; the European Medical Association (EMANET); the Observatoire Social Européen (OSE); and The Netherlands Institute for Health Service Research (NIVEL). For questions about the report, please contact Dr Gabriele Birnberg ([email protected] ). Matrix Insight | 24 January 2012 2 Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Executive Summary This study has been carried out in the context of Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross- border healthcare (CBHC). The CBHC Directive stipulates that the European Commission shall adopt measures to facilitate the recognition of prescriptions issued in another Member State (Article 11). At the time of submission of this report, the European Commission was preparing an impact assessment with regards to these measures, designed to help implement Article 11. -

A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, Pka, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Comparative Study of Molecular Structure, pKa, Lipophilicity, Solubility, Absorption and Polar Surface Area of Some Antiplatelet Drugs Milan Remko 1,*, Anna Remková 2 and Ria Broer 3 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Comenius University in Bratislava, Odbojarov 10, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Slovak Medical University, Limbová 12, SK–833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 3 Department of Theoretical Chemistry, Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-2-5011-7291 Academic Editor: Michael Henein Received: 18 February 2016; Accepted: 11 March 2016; Published: 19 March 2016 Abstract: Theoretical chemistry methods have been used to study the molecular properties of antiplatelet agents (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel, elinogrel, ticagrelor and cangrelor) and several thiol-containing active metabolites. The geometries and energies of most stable conformers of these drugs have been computed at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of density functional theory. Computed dissociation constants show that the active metabolites of prodrugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel) and drugs elinogrel and cangrelor are completely ionized at pH 7.4. Both ticagrelor and its active metabolite are present at pH = 7.4 in neutral undissociated form. The thienopyridine prodrugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel and prasugrel are lipophilic and insoluble in water. Their lipophilicity is very high (about 2.5–3.5 logP values). The polar surface area, with regard to the structurally-heterogeneous character of these antiplatelet drugs, is from very large interval of values of 3–255 Å2. -

Preventive Medication Program

PREVENTIVE MEDICATION PROGRAM Generics and Preferred Brands Drug List Starting July 1, 2021 Preventive medications are used to prevent certain conditions from developing, or to prevent a condition from coming back. These conditions include, but are not limited to, asthma, depression, diabetes, heart attack, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, osteoporosis, prenatal nutrient deficiency and stroke. About this drug list. Your cost-share for preventive generic and This is a list of the most commonly prescribed generic preferred brand medications. and preferred brand medications that are part of Not all plans offer the same cost-share for their Cigna’s preventive medication program as of July preventive medication program. For example, some 1, 2021.1,2 This drug list is updated often so it isn’t a plans may require you to pay a copay, coinsurance complete list of medications. Also, your specific plan’s and/or deductible for preventive generic and preferred preventive medication program may not include all brand medications; other plans may not. of these medications and/or conditions. Log in to the Log into the myCigna App or myCigna.com and use myCigna® App or myCigna.com, or check your plan the Price a Medication tool to see how much your materials, to see all of the medications included in your medication may cost you at the different pharmacies in plan’s preventive medication program and how much your plan’s network.3 they cost. Here’s some helpful information about this drug list: › Medications are listed alphabetically by condition. › Brand-name medications are capitalized and generic medications are lowercase. -

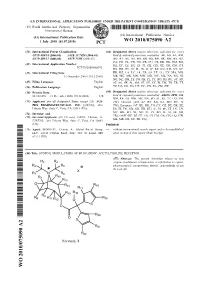

Wo 2010/075090 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 July 2010 (01.07.2010) WO 2010/075090 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 409/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/7028 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 409/12 (2006.01) A61P 11/06 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2009/068073 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 15 December 2009 (15.12.2009) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (26) Publication Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/122,478 15 December 2008 (15.12.2008) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AUS- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, PEX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Preventive Generic Drugs Listing

2017 PREVENTIVE DRUG LIST Preventive medications are used for the prevention of conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, asthma, osteoporosis, heart attack, stroke and prenatal nutrient deficiency. You may not have to pay a copay, a coinsurance (the percentage you pay after you meet your deductible) and/or a deductible (the amount you pay before your plan starts to pay) for preventive medications. Please check your plan’s prescription drug list and This list is subject to change and may not include all plan documents to understand how your plan covers preventive medications that your plan covers. Please preventive medications. You can refer to myCigna.com refer to your plan’s prescription drug list for a complete for a complete and up-to-date drug listing for your plan. and up-to-date drug listing. You can also use the Prescription Drug Price Quote tool on myCigna.com to view and compare drug prices. The following is a list of generic and brand-name If you have questions preventive medications, arranged by type of condition. Please call the toll-free number on the back of Talk with your doctor when choosing the preventive your Cigna ID card. We’re here to help. medication that is right for you. Also talk with your doctor about available generic preventive medications (listed as uncapitalized medications and/or in parentheses). Generic medications have the same active ingredients, dosage form, quality and strength, as their brand-name counterparts and may provide additional savings for you. Offered by: Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company, or their affiliates. -

Hydrophilic Polymer Embolism: Implications for Manufacturing, Regulation, and Postmarket Surveillance of Coated Intravascular Medical Devices

Clinical and Translational Science Institute Centers 3-19-2018 Hydrophilic Polymer Embolism: Implications for Manufacturing, Regulation, and Postmarket Surveillance of Coated Intravascular Medical Devices Rashi I. Mehta West Virginia University Rupal I. Mehta University of Rochester Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Digital Commons Citation Mehta, Rashi I. and Mehta, Rupal I., "Hydrophilic Polymer Embolism: Implications for Manufacturing, Regulation, and Postmarket Surveillance of Coated Intravascular Medical Devices" (2018). Clinical and Translational Science Institute. 926. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi/926 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centers at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Clinical and Translational Science Institute by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Patient Manuscript Author Saf. Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2019 September 19. Hydrophilic Polymer Embolism: Implications for Manufacturing, Regulation, and Postmarket Surveillance of Coated Intravascular Medical Devices Rashi I. Mehta, MD1 and Rupal I. Mehta, MD2,3,4,5,* 1West Virginia University, Department of Radiology 2University of Rochester Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 3Department of Neuroscience 4Center for Neurotherapeutics Discovery (CND) 5Center for Translational Neuromedicine (CTN) Abstract Hydrophilic polymers are ubiquitously applied as surface coatings on catheters and intravascular medical technologies. Recent clinical literature has heightened awareness on the complication of hydrophilic polymer embolism (HPE), the phenomenon wherein polymer coating layers separate from catheter and device surfaces, and may be affiliated with a range of unanticipated adverse reactions. -

MEDICINE to TREAT: HEART DISEASES Antiplatelet Agents Aspirin Dipyridamole Clopidogrel Ticlopidine 1. What Are These Medicines U

PATIENT INFORMATION LEAFLET MEDICINE TO TREAT: HEART DISEASES Antiplatelet Agents Aspirin Dipyridamole Clopidogrel Ticlopidine 1. What are these medicines used for? Medicine Purpose of medicine Brand Names This medicine makes blood less sticky to reduce the chance of blood forming Aspirin Cardiprin® clots which will lead to stroke or heart Disprin® attack. This medicine makes the blood less Dipyridamole sticky to reduce the chance of stroke. It Persantin® is used together with aspirin. These medicines make your blood less Clopidogrel (Plavix®) Clopidogrel sticky to reduce chance of stroke or Ticlopidine (Ticlid®), Ticlopidine heart attack. They can be used alone or together with aspirin. 2. How should I take the medicines? • Do not stop taking your medicines without checking with your doctors. • If you miss a dose, take the missed dose as soon as you remember. If it is almost time for your next dose, take only the usual dose. Do not double your dose or use extra medicine to make up for the missed dose. • You should take your medicine after a meal to prevent stomach upset. • How you take aspirin depends on the brand and type of aspirin the doctor gives you: o For tablets which can be chewed: Take with food or glass of water or milk These tablets may be chewed or swallowed whole The solution may also be used as a gargle. Please check with your pharmacist on how to use it as a gargle. o For tablets which enteric coated: Enteric coated forms of aspirin reduce stomach upset that is caused by the medicine Take with a glass of water after food. -

Clinical Update

Atualização Clínica Antiagregantes Plaquetários na Prevenção Primária e Secundária de Eventos Aterotrombóticos Platelet Antiaggregants in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Atherothrombotic Events Marcos Vinícius Ferreira Silva1, Luci Maria SantAna Dusse1, Lauro Mello Vieira, Maria das Graças Carvalho1 Departamento de Análises Clínicas e Toxicológicas, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais1, Belo Horizonte, MG – Brasil Resumo prevenção primária e secundária de tais eventos. Os fatores A aterotrombose e suas complicações correspondem, de risco associados ao desenvolvimento desses eventos hoje, à principal causa de mortalidade no mundo todo, estão intimamente associados à exacerbação da ativação e sua incidência encontra-se em franca expansão. plaquetária que, por sua vez, favorece a formação de As plaquetas desempenham um papel essencial na agregados plaquetários e geração de trombina, resultando patogênese dos eventos aterotrombóticos, justificando a em trombos ricos em plaquetas (trombos brancos). Dessa utilização dos antiagregantes plaquetários na prevenção forma, o uso de antiagregantes plaquetários tem sido dos mesmos. Desse modo, é essencial que se conheça o benéfico na prevenção primária e secundária de eventos perfil de eficácia e segurança desses fármacos em prevenção mediados por trombos. primária e secundária de eventos aterotrombóticos. Dentro As características dos principais antiagregantes plaquetários desse contexto, a presente revisão foi realizada com o utilizados na prática clínica e em fase de estudos estão objetivo de descrever e sintetizar os resultados dos principais descritos na Tabela 13-9, e as proteínas de membrana com as ensaios, envolvendo a utilização de antiagregantes nos dois quais eles interagem e as vias metabólicas nas quais atuam níveis de prevenção, e avaliando a eficácia e os principais são ilustrados Figura 110. -

Order in Council 1243/1995

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL Order in Council No. 12 4 3 , Approved and Ordered OCT 121995 Lieutenant Governor Executive Council Chambers, Victoria On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that Order in Council 1039 made August 17, 1995, is rescinded. 2. The Drug Schedules made by regulation of the Council of the College of Pharmacists of British Columbia, as set out in the attached resolution dated September 6, 1995, are hereby approved. (----, c" g/J1"----c- 4- Minister of Heal fandand Minister Responsible for Seniors Presidin Member of the Executive Council (This pan is for adnwustratlye purposes only and is not part of the Order) Authority under which Order Is made: Act and section:- Pharmacists, Pharmacy Operations and Drug Scheduling Act, section 59(2)(1), 62 Other (specify): - Uppodukoic1enact N6145; Resolution of the Council of the College of Pharmacists of British Columbia ("the Council"), made by teleconference at Vancouver, British Columbia, the 6th day of September 1995. RESOLVED THAT: In accordance with the authority established in Section 62 of the Pharmacists, Pharmacy Operations and Drug Scheduling Act of British Columbia, S.B.C. Chapter 62, the Council makes the Drug Schedules by regulation as set out in the attached schedule, subject to the approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council. Certified a true copy Linda J. Lytle, Phr.) Registrar DRUG SCHEDULES to the Pharmacists, Pharmacy Operations and Drug Scheduling Act of British Columbia The Drug Schedules have been printed in an alphabetical format to simplify the process of locating each individual drug entry and determining its status in British Columbia. -

RESEARCH PROTOCOL Role of CYP2B6 Polymorphisms In

RESEARCH PROTOCOL Role of CYP2B6 polymorphisms in ketamine metabolism and clearance Evan D. Kharasch, M.D., Ph.D. Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Professor of Anesthesiology Director, Division of Clinical and Translational Research Washington University School of Medicine Department of Anesthesiology 660 S. Euclid Ave., Campus Box 8054 St. Louis, Mo. 63110 Voice: (314) 362-8796 Fax: (314) 747-3371 E-mail: [email protected] Original Version: July 9, 2013 2 1. SYNOPSIS Study Title Role of CYP2B6 polymorphisms in ketamine metabolism and clearance Objective To determine the effects of cytochrome P4502B6 (CYP2B6) genetic variants on ketamine metabolism and clearance Study Design Single-center, open label, single-session study to evaluate ketamine pharmaco- kinetics in subjects with known CYP2B6 genotype Study Period Planned enrollment duration: Approximately 3 months. Planned study duration: 1 day per subject Number of Patients Approximately 40 healthy volunteers identified by CYP2B6 genotyping by HRPO-approved screening Inclusion and Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria a) 18-50 yr old b) CYP2B6*1/*1, CYP2B6*1/*6 or CYP2B6*6/*6 genotype c) Good general health with no remarkable medical conditions d) BMI < 33 e) Provide informed consent Exclusion Criteria a) Known history of liver or kidney disease b) Use of prescription or non-prescription medications, herbals, foods or chemicals known to be metabolized by or affecting CYP2B6 c) Females who are pregnant or nursing d) Known history of drug or alcohol addiction (prior or present addiction or treatment for addiction) e) Direct physical access to and routine handling of addicting drugs in the regular course of duty (a routine exclusion from studies of drugs with addiction potential) Study Medication Subjects will be studied on one occasion at Washington University in St.