The Submorphemic Structure of Amharic: Toward a Phonosemantic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ling 230/503: Articulatory Phonetics and Transcription English Vowels

Ling 230/503: Articulatory Phonetics and Transcription Broad vs. narrow transcription. A narrow transcription is one in which the transcriber records much phonetic detail without attention to the way in which the sounds of the language form a system. A broad transcription omits those details of a narrow transcription which the transcriber feels are not worth recording. Normally these details will be aspects of the speech event which are: (1) predictable or (2) would not differentiate two token utterances of the same type in the judgment of speakers or (3) are presumed not to figure in the systematic phonology of the language. IPA vs. American transcription There are two commonly used systems of phonetic transcription, the International Phonetics Association or IPA system and the American system. In many cases these systems overlap, but in certain cases there are important distinctions. Students need to learn both systems and have to be flexible about the use of symbols. English Vowels Short vowels /ɪ ɛ æ ʊ ʌ ɝ/ ‘pit’ pɪt ‘put’ pʊt ‘pet’ pɛt ‘putt’ pʌt ‘pat’ pæt ‘pert’ pɝt (or pr̩t) Long vowels /i(ː), u(ː), ɑ(ː), ɔ(ː)/ ‘beat’ biːt (or bit) ‘boot’ buːt (or but) ‘(ro)bot’ bɑːt (or bɑt) ‘bought’ bɔːt (or bɔt) Diphthongs /eɪ, aɪ, aʊ, oʊ, ɔɪ, ju(ː)/ ‘bait’ beɪt ‘boat’ boʊt ‘bite’ bɑɪt (or baɪt) ‘bout’ bɑʊt (or baʊt) ‘Boyd’ bɔɪd (or boɪd) ‘cute’ kjuːt (or kjut) The property of length, denoted by [ː], can be predicted based on the quality of the vowel. For this reason it is quite common to omit the length mark [ː]. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns 1 INTRODUCTION This study addresses the systematic relations in language between mean- ing and surface expression.1 (The word ``surface'' throughout this chapter simply indicates overt linguistic forms, not any derivational theory.) Our approach to this has several aspects. First, we assume we can isolate ele- ments separately within the domain of meaning and within the domain of surface expression. These are semantic elements like `Motion', `Path', `Figure', `Ground', `Manner', and `Cause', and surface elements like verb, adposition, subordinate clause, and what we will characterize as satellite. Second, we examine which semantic elements are expressed by which surface elements. This relationship is largely not one-to-one. A combina- tion of semantic elements can be expressed by a single surface element, or a single semantic element by a combination of surface elements. Or again, semantic elements of di¨erent types can be expressed by the same type of surface element, as well as the same type by several di¨erent ones. We ®nd here a range of universal principles and typological patterns as well as forms of diachronic category shift or maintenance across the typological patterns. We do not look at every case of semantic-to-surface association, but only at ones that constitute a pervasive pattern, either within a language or across languages. Our particular concern is to understand how such patterns compare across languages. That is, for a particular semantic domain, we ask if languages exhibit a wide variety of patterns, a com- paratively small number of patterns (a typology), or a single pattern (a universal). -

The Origin of the IPA Schwa

The origin of the IPA schwa Asher Laufer The Phonetics Laboratory, Hebrew Language Department, The Hebrew University, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem 91905, Israel [email protected] ABSTRACT We will refer here to those two kinds of schwa as "the linguistic schwa", to distinguish them from what The symbol ⟨ə⟩ in the International Phonetic Alphabet we call " the Hebrew schwa". was given the special name "Schwa". In fact, phoneticians use this term to denote two different meanings: A precise and specific physiological 2. HISTORY OF THE "SCHWA" definition - "a mid-central vowel" - or a variable The word "schwa" was borrowed from the vocabulary reduced non-defined centralized vowel. of the Hebrew grammar, which has been in use since The word "schwa" was borrowed from the Hebrew the 10th century. The Tiberian Masorah scholars grammar vocabulary, and has been in use since the th added various diacritics to the Hebrew letters to 10 century. The Tiberian Masorah scholars added, denote vowel signs and cantillation (musical marks). already in the late first millennium CE, various Actually, we can consider these scholars as diacritics to the Hebrew letters, to denote vowel signs phoneticians who invented a writing system to and cantillation (musical marks). Practically, we can represent their Hebrew pronunciation. Already in the consider them as phoneticians who invented a writing 10th century the Tiberian grammarians used this pronounced [ʃva] in Modern) שְׁ וָא system to represent pronunciation. They used the term Hebrew term ʃwa] and graphically marked it with a special Hebrew), and graphically marked it by two vertical] שְׁ וָא sign (two vertical dots beneath a letter [ ְׁ ]). -

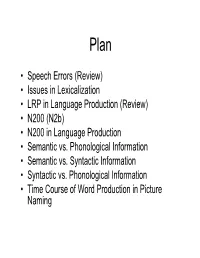

• Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic Vs

Plan • Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic vs. Phonological Information • Semantic vs. Syntactic Information • Syntactic vs. Phonological Information • Time Course of Word Production in Picture Naming Eech Sperrors • What can we learn from these things? • Anticipation Errors – a reading list Æ a leading list • Exchange Errors – fill the pool Æ fool the pill • Phonological, lexical, syntactic • Speech is planned in advance – Distance of exchange, anticipation errors suggestive of how far in advance we “plan” Word Substitutions & Word Blends • Semantic Substitutions • Lexicon is organized – That’s a horse of another color semantically AND Æ …a horse of another race phonologically • Phonological Substitutions • Word selection must happen – White Anglo-Saxon Protestant after the grammatical class of Æ …prostitute the target has been • Semantic Blends determined – Edited/annotated Æ editated – Nouns substitute for nouns; verbs for verbs • Phonological Blends – Substitutions don’t result in – Gin and tonic Æ gin and topic ungrammatical sentences • Double Blends – Arrested and prosecuted Æ arrested and persecuted Word Stem & Affix Morphemes •A New Yorker Æ A New Yorkan (American) • Seem to occur prior to lexical insertion • Morphological rules of word formation engaged during speech production Stranding Errors • Nouns & Verbs exchange, but inflectional and derivational morphemes rarely do – Rather, they are stranded • I don’t know that I’d -

153 Natasha Abner (University of Michigan)

Natasha Abner (University of Michigan) LSA40 Carlo Geraci (Ecole Normale Supérieure) Justine Mertz (University of Paris 7, Denis Diderot) Jessica Lettieri (Università degli studi di Torino) Shi Yu (Ecole Normale Supérieure) A handy approach to sign language relatedness We use coded phonetic features and quantitative methods to probe potential historical relationships among 24 sign languages. Lisa Abney (Northwestern State University of Louisiana) ANS16 Naming practices in alcohol and drug recovery centers, adult daycares, and nursing homes/retirement facilities: A continuation of research The construction of drug and alcohol treatment centers, adult daycare centers, and retirement facilities has increased dramatically in the United States in the last thirty years. In this research, eleven categories of names for drug/alcohol treatment facilities have been identified while eight categories have been identified for adult daycare centers. Ten categories have become apparent for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These naming choices function as euphemisms in many cases, and in others, names reference morphemes which are perceived to reference a higher social class than competitor names. Rafael Abramovitz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) P8 Itai Bassi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Relativized Anaphor Agreement Effect The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) is a generalization that anaphors do not trigger phi-agreement covarying with their binders (Rizzi 1990 et. seq.) Based on evidence from Koryak (Chukotko-Kamchan) anaphors, we argue that the AAE should be weakened and be stated as a generalization about person agreement only. We propose a theory of the weakened AAE, which combines a modification of Preminger (2019)'s AnaphP-encapsulation proposal as well as converging evidence from work on the internal syntax of pronouns (Harbour 2016, van Urk 2018). -

Lexicalization After Grammaticalization in the Development of Slovak Adjectives Ending In

Lexicalization after grammaticalization in the development of Slovak adjectives ending in -lý originating from l-participles Gabriela Múcsková, Comenius University and Slovak Academy of Sciences The paper deals with the development and current state of the Slovak participial forms, especially the participles with the formant -l- (the so-called l-participles) in the context of grammaticalization and lexicalization as complex and gradual changes. The analysis focuses on the group of “adjectives ending in -lý” as a result of “verb-to-adjective” lexicalization of former l-participles, which was conditioned by preceding grammaticalization of other members of the same participial paradigm. The group of lexemes identified in current Slovak descriptive grammatical and lexicographical works as “adjectives ending in -lý” is highly variable and includes a set of units of hybrid nature reflecting the overlapping of verbal and adjectival grammatical meanings and dynamic and static semantic components. Moreover, the group is rather limited, has irregular structural and derivational properties and is semantically rich, with extensive semantic derivation and polysemy. The characteristics of these units suggest a higher degree of their adjectivization, but the variability of the units reflects the different phases and degrees of this change, which was also influenced by language-planning factors in the Slovak historical context. Reconstruction of the phases of the adjectivization process, gradual decategorization and desemanticization, and reanalysis to a new structural and semantic class can serve as a contribution to more general questions about the nature of language change and its explanation. Keywords: participle, lexicalization, adjectivization, grammaticalization, lexicography 1. Introduction Linguistic descriptions of grammatical, word-formation and lexical structures are abstract reflexive constructs establishing boundaries between structural levels, parts of speech, categories and paradigms inside the language. -

Space in Languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O'meara

Space in languages in Mexico and Central America Carolyn O’Meara, Gabriela Pérez Báez, Alyson Eggleston, Jürgen Bohnemeyer 1. Introduction This chapter presents an overview of the properties of spatial representations in languages of the region. The analyses presented here are based on data from 47 languages belonging to ten Deleted: on literature covering language families in addition to literature on language isolates. Overall, these languages are located primarily in Mexico, covering the Mesoamerican Sprachbundi, but also extending north to include languages such as the isolate Seri and several Uto-Aztecan languages, and south to include Sumu-Mayangna, a Misumalpan language of Nicaragua. Table 1 provides a list of the Deleted: The literature consulted includes a mix of languages analyzed for this chapter. descriptive grammars as well as studies dedicated to spatial language and cognition and, when possible and relevant, primary data collected by the authors. Table 1 provides a Table 1. Languages examined in this chapter1 Family / Stock Relevant sub-branches Language Mayan Yucatecan Yucatecan- Yucatec Lacandon Mopan-Itzá Mopan Greater Cholan Yokot’an (Chontal de Tabasco) Tseltalan Tseltalan Tseltal Zinacantán Tsotsil Q’anjob’alan- Q’anjob’alan Q’anjob’al Chujean Jacaltec Otomanguean Otopame- Otomí Eastern Highland Otomí Chinantecan Ixtenco Otomí San Ildefonso Tultepec Otomí Tilapa Otomí Chinantec Palantla Chinantec 1 In most cases, we have reproduced the language name as used in the studies that we cite. However, we diverge from this practice in a few cases. One such case would be one in which we know firsthand what the preferred language name is among members of the language community. -

Speaking Words

Speaking Words: Contributions of cognitive neuropsychological research Brenda Rapp and Matthew Goldrick 1 Abstract We review the significant cognitive neuropsychological contributions to our understanding of spoken word production that were made during the period of 1984 to 2004- since the founding of the journal Cognitive Neuropsychology. We then go on to identify and discuss a set of outstanding questions and challenges that face future cognitive neuropsychological researchers in this domain. We conclude that the last twenty years have been a testament to the vitality and productiveness of this approach in the domain of spoken word production and that it is essential that we continue to strive for the broader integration of cognitive neuropsychological evidence into cognitive science, psychology, linguistics and neuroscience. 2 INTRODUCTION The founding of Cognitive Neuropsychology in 1984 marked the recognition and “institutionalization” of a set of ideas that had been crystallizing for a number of years. These ideas formed the basis of the cognitive neuropsychological approach and, thus, have largely defined the journal over the past twenty years (Caramazza, 1984, 1986; Ellis, 1985, 1987; Marin, Saffran, & Schwartz, 1976; Marshall, 1986; Saffran, 1982; Shallice, 1979; Schwartz, 1984). Chief among them was an understanding of the fundamental limitations of syndromes or clinical categories as the vehicle for characterizing patterns of impairment. This was complemented by the realization that the appropriate and productive unit of analysis was the performance of the individual neurologically injured individual. Critical also was the more explicit formulation of the relationship between neuropsychology and cognitive psychology (Caramazza, 1986). The increasing application of theories of normal psychological processing to the analysis of deficits allowed neuropsychological evidence to provide significant constraints on theory development within cognitive psychology. -

THE ICONICITY of CONSONANTS in ACTION WORDS by XINJIA PENG

THE ICONICITY OF CONSONANTS IN ACTION WORDS by XINJIA PENG A THESIS Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Xinjia Peng Title: The Iconicity of Consonants in Action Words This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Chairperson Kaori Idemaru Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Xinjia Peng iii THESIS ABSTRACT Xinjia Peng Master of Arts The Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures June 2013 Title: The Iconicity of Consonants in Action Words Saurssure argues that the relationship between form and meaning in language is arbitrary, but sound symbolism theory argues that there are forms in language that can develop non-arbitrary association with meanings. This thesis proposes that there is a sound symbolic association between consonants and action words. To be more specific, a stop sound is likely to be associated with the action of percussion and a continuant sound with continuing movements. Evidence for such an association was found through three empirical studies. The findings of two experiments revealed that such an association is motivated by the gestures when pronouncing the consonants and by their phonetic features. -

The Semantics of Word Formation and Lexicalization

The Semantics of Word Formation and Lexicalisation In the study of word formation, the focus has often been on generating The Semantics of the form. In this book, the semantic aspect of the formation of new words is central. It is viewed from the perspectives of word formation rules and of lexicalization. Word Formation and Each chapter concentrates on a specific question about a theoretical concept or a word formation process in a particular language and adopts a theoretical framework that is appropriate to the study of this question. From general theoretical concepts of productivity and lexicalization, Lexicalization the focus moves to terminology, compounding and derivation. The theoretical frameworks that are used include Jackendoff’s Conceptual Structure, Langacker’s Cognitive Grammar, Lieber’s lexical semantic approach to word formation, Pustejovsky’s Generative Lexicon, Beard’s Lexeme-Morpheme-Base Morphology and the onomasiological approach to terminology and word formation. An extensive introduction gives a historical overview of the study of the semantics of word formation and lexicalization, explaining how the different theoretical frameworks used in the contributions relate to each other. Edited by This innovative approach to word formation and lexicalization is essential reading for scholars and advanced students in linguistics. Pius ten Hacken, formerly of Swansea University, is now Professor of Pius ten Hacken and Claire Thomas Translationswissenschaft at the Leopold-Franzens Universität, Innsbruck. Claire Thomas has recently -

Organised Phonology Data

id11101609 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ára OPD Risto Sarsa W Version 3.0, 3 December 2001 Organised Phonology Data ára Language [TCI] W Western Province Linguistic Classification (according to Wurm): Tonda Sub-Family, Morehead and Upper Maro Rivers Family, Trans-Fly Stock, Trans-New Guinea Phylum. Note: In the Tonda Sub-Family there is a dialect chain situation. Therefore, it is difficult ára language (as defined by to establish precise language boundaries. The W ’s Upper Peremka (Rouku) Language the present writer) comprises Wurm and, in part, Tonda Language Population estimate: 800 ékwa, Tékwa, Réku, Wámnefér, Ufaruwa Major Villages: Y Linguistic work done by: S.A. Wurm; SIL Data checked by: Risto Sarsa, March 2001 Data is based on 7 years of fieldwork. PHONEMIC AND ORTHOGRAPHIC INVENTORY (In parentheses: only in loan words) z ŋ ŋɡ۽ɑ æ (b) (d) e ə f (ɡ) i k (l) m mb n nd? nG / < a á (b) (d) e é f (g) i,y k (l) m mb n nd,nt nj, nts ng nḡ < A Á (B) (D) E É F (G) I,Y K (L) M Mb N Nd Nj Ng Nḡ / s u ʉ w j۽o ʌ œ (p) r s t? ð W o ó ô (p) r s t th ts u,w ú w y > O Ó Ô (P) R S T Th Ts U,W Ú W Y > Page 1 of 12 File: Wara (Convert'd)2 ára OPD Risto Sarsa W Version 3.0, 3 December 2001 CONSONANTS Simple Consonants Bilab LabDen Dent Alv PsAl Retr Pala Velr Uvlr Phar Glot Plosive W ݽ k Nasal m n ŋ Trill r Fricat f ð s j Approx Complex Consonants mb (prenasalised voiced bilabial stop) nd? (prenasalised voiced dental stop) ŋɡ (prenasalised voiced velar stop) (s (voiceless alveolar grooved affricate۽W (z (prenasalised voiced alveolar grooved affricate۽nG w (voiced labio-velar approximant) The phonemes / b / , / d / , / g / , / l / and / p / only occur in loan words.