The Use of Entheogens in the Vajrayana Tradition: a Brief Summary of Preliminary Findings Together with a Partial Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Malleability of Yoga: a Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 25 Article 4 November 2012 The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jain, Andrea R. (2012) "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 25, Article 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Jain: The Malleability of Yoga The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis FOR over three thousand years, people have yoga is Hindu. This assumption reflects an attached divergent meanings and functions to understanding of yoga as a homogenous system yoga. Its history has been characterized by that remains unchanged by its shifting spatial moments of continuity, but also by divergence and temporal contexts. It also depends on and change. This applies as much to pre- notions of Hindu authenticity, origins, and colonial yoga systems as to modern ones. All of even ownership. Both Hindu and Christian this evidences yoga’s malleability (literally, the opponents add that the majority of capacity to be bent into new shapes without contemporary yogis fail to recognize that yoga breaking) in the hands of human beings.1 is Hindu.3 Yet, today, a movement that assumes a Suspicious of decontextualized vision of yoga as a static, homogenous system understandings of yoga and, consequently, the rapidly gains momentum. -

Unbalanced Flows in the Subtle Body: Tibetan Understandings of Psychiatric Illness and How to Deal with It

Journal of Religion and Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00774-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Unbalanced Flows in the Subtle Body: Tibetan Understandings of Psychiatric Illness and How to Deal With It Geofrey Samuel1,2 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Much of what Western medicine classifes as psychiatric illness is understood by Tibetan thought as associated with imbalance of rlung (wind, breath). Rlung has a dual origin in Indian thought, combining elements from Ayurvedic medicine and Tantric Buddhism. Tibetan theories of rlung seem to correspond in signifcant ways with Western concepts of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and Western medi- cine too has associated psychiatric issues with ANS problems. But what is involved in relating Tibetan ideas of rlung to Western ideas of the emotions and the ANS? The article presents elements of the two systems and then explores similarities and diferences between them. It asks whether the similarities could be the basis for a productive encounter between Tibetan and Western modes of understanding and treating psychiatric illness. What could Western psychiatry learn from Tibetan approaches in this area? Keywords Psychiatric illness · Tibet · Buddhism · Tantra · Subtle body · Autonomic nervous system Introduction As Susannah Deane’s article in this collection explains (Deane, this issue), much of the domain of psychiatric illness in biomedicine is understood in Tibetan medicine in terms of disorders in an internal process known as rlung (pronounced ‘loong’), sometimes translated as ‘wind.’ In this article, I examine the use of rlung as an explanation for psychiatric illness and ask how it might relate to biomedical and neuroscientifc modes of explanation for psychiatric disorders. -

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Living Landscapes

Introduction Yoga and Landscapes This book explores the practice of Yoga in regard to a systematic technique of performing concentration on the five elements. It examines some ideas that also concerned the pre-Socratic philosophers of Greece. Just as Thales mused about water and Heraclitus extolled the power of fire, Indian thinkers, theologians, and liturgists reflected on how the elements interweave with one another and within the human body to create the raw material for the experience of life. In a real and metaphorical sense, according to Indian thought, we live in landscapes and landscapes live in us. For more than 3,500 years, India has identified earth, water, fire, air, and space as the foundational building blocks of external reality. Starting with literary praise of these elements in the Vedas, by the time of the Buddha, the Upaniṣads, and early Jainism, this acknowledgment had grown into a systematic reflection. This book examines both the descriptions of the elements and the very technical training tools that emerged so that human beings might develop regard and consideration for them. Hindus, Buddhists, and Jain Yogis explore the human-earth relationship each in their own way. For Hindus, nature emerges as a theme in the Vedas, the Upaniṣads, the Yoga literature, the epics, and the Purāṇas. The Yogis develop a mental discipline of sustained interiorization, known as pañca mahābhūta dhāraṇā (concentration on the five great elements) and as bhūta śuddhi (purification of the elements). The Buddha himself also taught a sequential meditation on the five elements. The Jains developed their own unique reflections on nature, finding life in particles of earth, water, fire, and air. -

Under Memberships

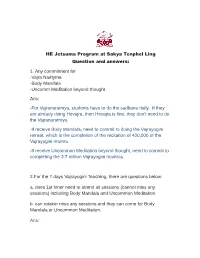

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature 4 1. Buddhist Tantric Literature Lama Anagarik Govinda wrote: “the word ‘Tantrd is related to the concept of weaving and its derivatives (thread, web, fabric, etc.), hinting at the interwovenness of things and actions, the interdependence of all that exists, the continuity in the interaction of cause and effect, as well as in spiritual and'traditional development, which like a thread weaves its way through the fabric of history and of individual lives. The scriptures which in Buddhism go under the name of Tantra (Tib.: rgyud) are invariably of a mystic nature, i.e., trying to establish the inner relationship of things: the parallelism of microcosm and macrocosm, mind and universe, ritual and reality, the world of matter and the world of the spirit.”99 Scholars like N.N. Bhattacharyya and also Pranabananda Jash, regard Tantra as a religious system or science (Sastra) dealing with the means (sadhana) of attaining success (siddhi) in secular or religious efforts.100 N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions that “Tantra came to mean the essentials of any religious system and, subsequently, special doctrines and rituals found only in certain forms of various religious systems. This change in the meaning, significance, and character of the word ‘Tantra' is quite striking and is likely to reveal many hitherto unnoticed elements that have characterised the social fabric of India through the ages.”101 It is must be noted that the Tantrika tradition is not the work of a day, it has a long history behind it. Creation, maintenance and dissolution, 99 Lama Anagarika Govinda, Foundations of Tibetan Myticism (Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1969), p.93. -

Chinese and Tibetan Tantric Buddhism

THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM THE ISRAEL INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES International Research Conference of the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (IIAS) and the Israel Science Foundation with additional support from the Louis Freiberg Center for East Asian Studies and the Confucius Institute, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem CHINESE AND TIBETAN TANTRIC BUDDHISM June 16-18, 2014 All lectures will take place at the Feldman Building, on the Edmond J. Safra, Givat Ram Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Organizers: Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University) Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University) PROGRAM Monday, June 16 9:30 Gathering 10:00 Greetings: Michal Linial (Director, IIAS) 10:30-12:00 ESOTERIC BUDDHISM AND CHINESE RELIGION Robert H. Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) Esoteric Buddhist Influence on the Emergence of Chan in Eighth Century China Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University & IIAS) The Tantric Origins of the Horse King: Hayagrīva and the Chinese Horse Cult Vincent Durand-Dastès (INALCO, Centre d’études chinoises, Equipe ASIEs, Paris) Esoteric Buddhism, Violence and Salvation in Ming-Qing Vernacular Novels 12:00-13:30 Lunch break 13:30-15:00 TIBETAN TANTRIC SCRIPTURES Jacob P. Dalton (University of California, Berkeley) Observations on the Ārya-tattvasaṃgraha-sādhanopāyikā and Its Commentary from Dunhuang Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem & IIAS) Conflicting Positions over the Interpretation of the Body Maṇḍala Jampa Samten (Central University for Tibetan Studies, Varanasi & IIAS) The Secret Signs (Chommaka) -

Self-Initiation Text

The Quick Path to Great Bliss: The Uncommon Sadhana of Venerable Vajrayogini Naro Khechari Together with the Self-Initiation Ritual, The Mandala Rite, Banquet of Great Bliss Arranged Simply and Clearly for the Sake of Easy Verbal Recitation Even if you have received [a highest yoga tantra] initiation and the blessing [initiation] of Vajrayogini, if you have not received the profound instructions on the two stages, refrain from reading this. With great respect, I prostrate to the feet of the guru, inseparable from Venerable Vajrayogini. With your great compassion, please care for me. A. Prepara@on Yogas 1, 2, and 3 To start, perform the first yoga of sleeping, the second yoga of waking, and the third yoga of tas@ng nectar. 4. Yoga of Immeasurables Sit with the physical essen@als [of the seven-fold posture] and recite: Dün gyi nam khar la ma khor lo dom pa yab yum la tsa gyü kyi la ma yi dam chhog sum ka dö sung mäi tshog kyi kor nä zhug par gyur In the space before me are Guru Chakrasamvara father and mother, encircled by the assemblies of root and lineage gurus, yidams, the Three Jewels, Dharma protectors, and guardians. Taking Refuge Imagine yourself and all sen@ent beings going for refuge: Dag dang dro wa nam khäi tha dang nyam päi sem chän tham chä dü di nä zung te ji si jang chhub nying po la chhi kyi bar du I and all living beings, equaling the limits of space, from now unAl reaching the essence of enlightenment, Päl dän la ma dam pa nam la kyab su chhi o Go for refuge to the glorious holy gurus; Dzog päi sang gyä chom dän dä nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the complete buddha bhagavans; Dam päi chhö nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the holy Dharma; Phag päi gen dün nam la kyab su chhi o (3x) We go for refuge to the arya Sangha. -

The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century Geoffrey Samuel Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87351-2 - The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century Geoffrey Samuel Frontmatter More information THE ORIGINS OF YOGA AND TANTRA Yoga, Tantra and other forms of Asian meditation are practised in modernised forms throughout the world today, but most introduc- tions to Hinduism or Buddhism tell only part of the story of how they developed. This book is an interpretation of the history of Indic reli- gions up to around 1200 CE, with particular focus on the development of yogic and Tantric traditions. It assesses how much we really know about this period, and asks what sense we can make of the evolution of yogic and Tantric practices, which were to become such central and important features of the Indic religious scene. Its originality lies in seeking to understand these traditions in terms of the total social and religious context of South Asian society during this period, includ- ing the religious practices of the general population with their close engagement with family, gender, economic life and other pragmatic concerns. geoffrey samuel is Professorial Fellow at the School of Reli- gious and Theological Studies at Cardiff University. His publications include Mind, Body and Culture: Anthropology and the Biological Inter- face (2006). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87351-2 - The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century Geoffrey Samuel Frontmatter More information THE ORIGINS OF YOGA AND TANTRA -

The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, Or All Three?

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 4-20-2020 The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three? Kathryn Heislup Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Heislup, Kathryn, "The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three?" (2020). Student Research Submissions. 325. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/325 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Subtle Body: Religious, Spiritual, Health-Related, or All Three? A Look Into the Subtle Physiology of Traditional and Modern Forms of Yoga Kathryn E. Heislup RELG 401: Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Major in Religion University of Mary Washington April 20, 2020 2 Notions of subtle body systems have migrated and changed throughout India and Tibet over many years with much controversy; the movement of these ideas to the West follows a similar controversial path, and these developments in both Asia and the West exemplify how one cannot identify a singular, legitimate, “subtle body”. Asserting that there is only one legitimate teaching, practice, and system of the subtle body is problematic and inappropriate. The subtle body refers to assumed energy points within the human body that cannot be viewed by the naked eye, but is believed by several traditions to be part of our physical existence. Indo-Tibetan notions of a subtle body do include many references to similar ideas when it comes to this type of physiology, but there has never been one sole agreement on a legitimate identification or intended use. -

A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia

Spencer Ames 2/19/19 A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia The Khmer kingdom (12th – 13th century): King Jayavarman VII and his Wife Indradevi. I first encountered the ruins of Cambodia’s ancient kingdoms on a family trip many years ago. My brother and I were climbing through thick vines and over giant tree roots entwining ancient carved stones. There were Buddha images throughout the intricately carved ruins, most of them decapitated or worn down to being almost unrecognizable by time and the overgrown jungle. I was a Buddhist myself and these ruins spoke to me at a deep level. My little bit of research at that time into these amazing ruins hinted that the Mahayana and Vajrayana were once practiced there. Twelve years passed and I found myself about to move to Cambodia for a year, and my initial curiosity was sparked again. While living there I dove into whatever research I could find on ancient and modern Buddhism in Cambodia and discovered a surprising link to my own Drikung Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist lineage. In the 12-13th century in Cambodia, and perhaps up to a few centuries before that, the Heruka tantras of Hevajra and Chakrasamvara made their way to the Khmer kingdom in Cambodia. There is little information that has survived to the present from these Vajrayana lineages, due to the secret nature of the teachings, and later to a nearly complete suppression and destruction of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism by successive Hinayana, Hindu and Communist rulers. The small amount of information we do know primarily comes to us from the time of King Jayavarman VII (1125–1218 AD) who is generally considered Cambodia’s most famous and powerful king. -

Readingsample

Contributions to Tibetan Studies 6 Hevajra and Lam’bras Literature of India and Tibet as Seen Through the Eyes of A-mes-zhabs Bearbeitet von Jan-Ulrich Sobisch 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. ca. 264 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 89500 652 4 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 616 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Buddhismus > Tibetischer Buddhismus Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. General introduction to the transmission of the Hevajra teachings In the following, I would like to provide an introduction to this study of the Hevajra teachings (and subsequent to that to the Path with Its Fruit teachings) that is accessible to both those who do read the Tibetan language and those who do not. I have therefore abstained in these two introductory chapters from using the regular Wylie transliteration of Tibetan names, and I have translated an abbreviated form of all titles of Tibetan works mentioned. I am sure that all names, which I have rendered here in an approximate phonetic transliteration, will be easily recognizable to the expert. To ensure, furthermore, the expert’s recognition of the translated titles of works, I have added the Tibetan abbreviated form of titles in Wylie transcription in brackets. For all bibliographical references, please refer to the main part of the book.