Toward a Unity Oj Performance and Musicology Rosalyn Tureck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firlngllne Copyright University

rights other a All infringement. makes resale. for user a copyright not If for are liable material. be Copies may 94305-6010 user copyrighted prohibited. CA of is that use, New FIRlnGLlne This Transcripts 29205 HOST GUESTS FIRING Stanford, SUBJECT fair distribution of is reproductions York 8031799-3449 : a and further transcript LINE excess University, : other videocassettes : City in or and is , March "IS WILLIAM Stanford produced material. ROSALYN of reprints purposes a re GOOD this FIRING available for photocopies of 31, of Archives, and 1999, additional MUSIC through copies) re-use and Copyright F. LINE TURECK making directed BUCKLEY, any and Producers the Library program purposes; GOING telecast 1999 before handwritten by Inc and governs o FIRING WARREN rporated Institution owner SCHUYLER #2833/1200, UNDER?" JR. later educational Code) (including fo LINE and Hoover r on Television, U.S. copyright public University. 17, STEIBEL. the Jr. Director, taped CHAPIN reproduction 2700 (Title from television or Cypress Stanford contact at non-commercial, States HBO Street, permission photocopy Leland stations United private, a Columbia, Studios the for the obtain information, of is uses of to . SC later laws further in or material Trustees advised For of for, this are of copyright ©Board reserved. Users Use The request © Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. MR. BUCKLEY: Every few years Firing Line touches down on the question, Is classical music dying? We are lucky enough this time around to have got in to discuss the question two persons who have spoken to us before on the subject. One is perhaps the most distinguished pianist alive, the second, the senior man of music in New York City. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

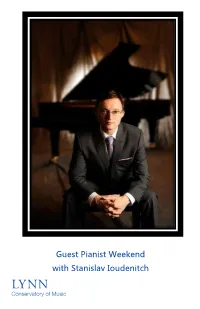

2016-2017 Master Class-Stanislav Ioudenitch

Guest Pianist Weekend with Stanislav Ioudenitch Pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch In Recital Saturday, Dec. 3 7:30 p.m. Count and Countess de Hoernle International Center Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall PROGRAM Spanish Rhapsody Franz Liszt Partita No. 2 in C minor JS Bach Sinfonia Allemande Courante Sarabande Rondeaux Capriccio Moment Musicaux Franz Schubert No. 3 Allegro moderato in F minor No. 4 Moderato in C-sharp minor Sonata No. 2 (1913 edition) Sergei Rachmaninoff Allegro agitato Non allegro Allegro molto Artist Biography STANISLAV IOUDENITCH has garnered notable successes in music competitions including the Gold Medal at the XI Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001. The Van Cliburn Competition launched a career that has taken Ioudenitch around the world for appearances with major venues, including Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, Fort the Moscow Conservatoire, Mariinsky Concert Hall, the Great Hall of the St Petersburg Philharmonic, the Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi in Milan, the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, the Oriental Art Center in Shanghai and appeared at major festivals including the International Piano Festival in the United States and the Ruhr Music Festival in Germany among others. Ioudenitch has collaborated with a wide range of international conductors including James Conlon, Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, Asher Fisch, Vladimir Spivakov, Günther Herbig, Pavel Kogan, James DePreist, Michael Stern, Stefan Sanderling, Carl St. Clair and Justus Frantz, and with such orchestras as the National Symphony in Washington DC, the Munich Philharmonic, Mariinsky Orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic, the National Philharmonic of Russia, the Fort Worth Symphony and the Kansas City Symphony among others. He has also performed with the Takács, Prazák and Borromeo String Quartets and is a founding member of the Park Piano Trio. -

Bach's Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations - A survey of the piano recordings by Ralph Moore Let me say right away that while I am well aware that Bach specified on the title page that these variations are for harpsichord, I much prefer them played on the modern piano in what is technically a transcription and venture to suggest that Bach would have loved the sonorities and flexibility of the modern instrument, even though it inevitably involves essentially faking the changes of register available on a double manual harpsichord. I hardly seem to be alone in this, in that, just as every great cellist wants to engage with the Cello Suites, so almost every great pianist seems to want to record his or her interpretation of the Goldbergs for posterity and the public appetite for recordings and performances on the pianoforte seems undiminished. I have accordingly confined this survey to that category; doubtless more authentic accounts on an original instrument have great merit but they lie beyond my scope, knowledge and experience; I have neither the acquaintance with, nor appreciation for, harpsichord versions to attempt a meaningful conspectus of them; nor, indeed, do I have the recording on my shelves and leave that task to a better-qualified reviewer. Here, however, is a good collective survey of the harpsichord recordings from The Classic Review aimed at the average punter like me. In common with many a devotee of this miraculous music, my own first encounter with it was via the second Glenn Gould recording when, many years ago, a cultivated girlfriend introduced me to it; it was love at first hearing (assisted, perhaps by my attachment to said lady, but that’s another story…). -

Rosalyn Tureck Appointed Professor of Music

Rosalyn Tureck appointed Professor of Music May 17, 1966 Rosalyn Tureck, famed concert pianist and harpsichordist, has accepted appointment as Professor of Music at the University of California, San Diego it has been announced by University President Clark Kerr and San Diego Chancellor John S. Galbraith. Miss Tureck, one of the two or three outstanding proponents of baroque music in the world today, will join the faculty on July 1. She will teach in the newly formed Department of Music at Muir College, the second of 12 colleges planned for the UCSD campus. Muir College will accept its first students in the fall of 1967. In the meantime, Miss Tureck and the other members of the Muir College faculty will be engaged in the development of curriculum as well as teaching classes in the fine arts at Revelle College. Rosalyn Tureck is internationally acclaimed as "the greatest scholar and interpreter of Bach in the world today". She was born in Chicago where, at the age of 14, she was urged to specialize in Bach by her teacher, Jan Chiapusso. A year later she gave two all-Bach recitals in Chicago, and the following year, at the age of 16, won a full scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music in New York. She graduated cum laude with Life Fellowship from Juilliard in 1935 and immediately began a series of concert tours through the United States and Canada. Since 1947 her tours have been international taking her to England, Europe, Israel, South America and South Africa. In 1956, Miss Tureck began to conduct concerto and orchestral performances of Bach with the Collegium Musicum in Copenhagen. -

Why the Theremin Fell by the Wayside a Case Study in the Evolution of Paradigms in Music

Why the Theremin Fell By the Wayside A case study in the evolution of paradigms in music By: John Waymouth Sufficiency Course Sequence: Course Number Course Title Term HI1332 Introduction to the History of Technology A00 MU1611 Fundamentals of Music I A01 MU1612 Fundamentals of Music II B01 MU3611 Computer Techniques in Music C02 MU3612 Computers and Synthesizers in Music D02 Presented to: Professor Frederic Bianchi Department of Humanities and Arts Term B, 2004 Project FB-MU09 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of The Humanities and Arts Sufficiency Program Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester, Massachusetts Abstract The theremin was the first major electronic musical instrument. Play- ers cause the theremin to produce sound without contact at all by ma- nipulating electromagnetic fields with their hands. This unique design often sparks interest in those that learn about it, but despite this fact, the theremin has remained in relative obscurity since its invention. This paper discusses the history of the theremin and explains why it failed to gain widespread adoption, drawing on research in the growing field of memetics. i Contents 1 The Theremin 1 2 Background 2 2.1 The Invention ............................. 2 2.2 Clara Rockmore ........................... 4 2.3 Termen Returns to Russia ...................... 5 2.4 The Mid-Century ........................... 6 2.5 The Present Day ........................... 7 3 Why the Theremin Failed to Thrive 7 3.1 Interface Problems .......................... 8 3.2 Instruction .............................. 11 3.3 A Series of Unfortunate Events ................... 11 3.4 Memetics ............................... 12 3.4.1 Universal Darwinism ..................... 12 3.4.2 Techniques Memes Use .................... 14 3.4.3 Instrument Interfaces as Memes .............. -

Annotated Bibliography of Sources on the History of Piano Pedagogy Compiled by Members of the NCKP Historical Perspectives Committee

Annotated Bibliography of Sources on the History of Piano Pedagogy Compiled by Members of the NCKP Historical Perspectives Committee Connie Arrau Sturm (CAS) – Committee Chairman Debra Brubaker Burns (DBB) Anita Jackson (AJ) General historical surveys Boardman, Roger Crager. “A History of Theories of Teaching Piano Technic.” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1954. Boardman investigated how theories of teaching piano technique changed from 1753 to 1953. He classified the theories into three categories - finger technique, use of the arm, and weight/relaxation. Within each category of theories, he not only analyzed how the body was used and how it interacted with the instrument, but also discussed how these techniques were taught. Boardman’s comparisons among theories helped pinpoint when important changes occurred, revealing the special contributions of each pedagogue. Boardman concluded that concepts of piano technique evolved from use of fingers only, to the coordination of the entire body (highlighting the importance of the brain). He also noted the strong influence of environmental factors (e.g., changes in the instrument, changes in the repertoire, and inspiration of great performers of the day) on the development of theories of teaching piano technique. (CAS) Bomberger, E. Douglas, Martha Dennis Burns, James Parakilas, Judith Tick, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Mark Tucker. “The Piano Lesson” In Piano Roles: Three Hundred Years of Life with the Piano. James Parakilas, 133-179. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1999. This chapter chronicled how teaching piano and studying piano have changed over the centuries. The authors described the evolution of piano study from eighteenth-century daily lessons, where students practiced in the presence of the piano teacher, to nineteenth-century weekly lessons that required long hours of daily practice in between. -

“Goldberg Variations”—Glenn Gould (1955) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Tim Page (Guest Post)*

“Goldberg Variations”—Glenn Gould (1955) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Tim Page (guest post)* Glenn Gould Original label Original album In hindsight, one can almost believe that Glenn Gould had it all planned out--the unknown 22-year old Canadian pianist would come to America, astound the critics, win what would turn out to be a life-long record contract on the basis of a single concert, choose an austere and (then) rarely-heard work for his first album, turn that into a smash success, make himself world famous, and change the course of Bach interpretation forever. Foreseen or not, that’s pretty much what happened. Gould’s American debut--at the Phillips Gallery in Washington, DC, on January 2, 1955--elicited a rapturous response from the late Paul Hume, then the music critic for the “Washington Post”: Few pianists play the piano so beautifully, so lovingly, so musicianly in manner and with such regard for its real nature and its enormous literature…Glenn Gould is a pianist with rare gifts for the world. It must not long delay hearing and according him the honor and audience he deserves. We know of no pianist anything like him of any age. On the basis of a single performance, David Oppenheim, the director of Columbia Masterworks (now SONY Classical) signed Gould to an exclusive contract--and it was decided that the pianist's first recording would be the “Goldberg Variations.” It was an audacious choice for many reasons, and it is not surprising that some executives at Columbia felt a certain apprehension about launching a new artist in such esoteric repertory. -

Presented in Honor of the Centenary of Paul Mellon's Birth and Perfo

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 3:00 pm on weekdays. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. The Billy Rose Foundation Concerts National Gallery of Art Music Department Presented in honor of the National Gallery of Art centenary of Paul Mellon’s birth and Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw performed on the Ailsa Mellon Bruce Steinway Washington, DC Mailing address 2000b South Club Drive May 2, 9, 16, 23, and 30, and June 6, 2007 Landover, md 20785 Wednesday Afternoons, 12:10 pm www.nga.gov East Building Auditorium Admission free cover: Paul Stevenson Oles, 1971, National Gallery of Art Archives Introduction As the National Gallery celebrates the centenary of the birth of Paul Mellon (1907-1999), his generosity and that of the entire Mellon family, including Paul’s wife, Bunny, and his beloved sister, Ailsa Mellon Bruce (1901-1969), will be remembered. In 1940 Mrs. Mellon Bruce established the Avalon Foundation, which, among other things, funds the Gallery’s Andrew W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. In 1946 she designated funds for the Gallery’s purchase of American art and later made possible the acquisition of many old master works. Both she and her brother contributed large gifts to finance construction of the East Building, but Mrs. Mellon Bruce did not live to see its groundbreaking. Fler bequest to the Gallery included an endow ment fund and her own exquisite collection of small paintings by the French impressionists. -

The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World

The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World Reiko ISHII Key Words: Olga Samaroff, piano pedagogy, pianist, teaching philosophy 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the study This study examines the life and accomplishments of Olga Samaroff, one of the most famous and influential American musicians during the first half of the twentieth century, and discusses her contributions to music education and the musical world. Samaroff was an international concert pianist and a wife of the conductor Leopold Stokowski as well as a successful piano teacher and writer. This research begins with her biography, describes her pedagogical method and teaching philosophy, and then, discusses how her unique teaching method and high standards of musicianship influenced and contributed to culture and society in the U.S. 1.2 Significance of the study To date, research concerning Olga Samaroff is limited even though she made distinguished contributions to the classical music scene. Samaroff is a legendary but almost forgotten pianist of the early 1900’s who was overshadowed by Leopold Stokowski, her second husband as well as renowned conductor. Especially outside of the U.S., she is relatively unknown to most people and there is no publication available on Samaroff in Japan. In general, traditional piano teaching method is that student should follow what teacher says and imitate his or her teachers’ performance. Samaroff’s teaching method and philosophy were completely opposite from the traditional one. There were two purposes of her piano teaching, musical independence and human development of piano students. -

Pianist Paula Biedma at New York's Turtle Bay Music School

MUSIC Pianist Paula Biedma at New NEW YORK York's Turtle Bay Music School Fri, June 01, 2018 7:00 pm Venue Em Lee Concert Hall, Turtle Bay Music School, 244 E 52nd St, New York, NY 10022 View map Admission Free, RSVP at [email protected] More information Turtle Bay Music School Credits Organized by the Turtle Bay Music School with the collaboration of the Biedma presents a piano solo program featuring works by L. New York State Council on the Arts. V. Beethoven and P. I. Tchaikovsky at the Artist Series Supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department Concerts at Turtle Bay Music School. of Culture The Turtle Bay Music School (TBMS) organizes every year the Artist Series Concerts where the school’s faculty performs. Among the faculty, Spanish pianist Paula Biedma presents a program of piano solo music featuring works by L.V. Beethoven and P.I. Tchaikovsky. ABOUT PAULA BIEDMA Paula Biedma Fierro, a classical pianist from Madrid based in New York City, has performed as a soloist and with chamber groups in many different cities throughout Europe and America. She has appeared in venues such as the Brooklyn Museum (NYC), Auditorio del Palacio de Cibeles and Teatro Alcalá, Madrid (Spain), Real Coliseo Carlos III, El Escorial (Spain), Casa Da Música, Óbidos (Portugal), and Fundación Gilverto Alzate Avedaño, Bogotá, (Colombia). Biedma studied with teachers Anatoli Pouvznov and Nino Kereselidze in her hometown, Madrid. She graduated with honors from Conservatorio Superior de Música Padre Antonio Soler in San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Madrid). -

TRUE SISTERS: the Book Is a Translation from the Pioneers of a New Jewish Identity, 1843-1914

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 37, No. 1, Winter 2013 Revised from earlier print edition chicago jewish historical societ y chicago jewish history Talks, Tours, Art Exhibitions, Movies, Mah Jongg—Let’s Go! Ellen Weinberg Dreyfus has Save the Date! been the rabbi of B’nai Yehuda Beth Sholom in Leo Melamed Speaks Homewood, Illinois, since the congregation was on “Financial Markets founded in 1998 with the merger of Temple B’nai in Chicago and Jews” Yehuda and Congregation Beth Sholom. Sunday, May 19 Rabbi Dreyfus is past The CJHS open meeting on Sunday, May 19 will be president of the Central held at Emanuel Congregation, 5959 North Sheridan Conference of American Road, Chicago. The program begins at 2:00 p.m. Rabbis, the organization of Continued on page 14 nearly 2,000 Reform rabbis in North America and around the world. She is past president of the Chicago Board of Rabbis, the first woman to hold this office. Save the Date! Rabbi Ellen Dreyfus Speaks on “Women in the Rabbinate –Chicago” Sunday, April 14 The next open meeting of the Chicago Jewish Historical Society will be held on Sunday, April 14, 2:00 p.m., at Temple Beth Israel, 3601 West Dempster Street, Skokie. The featured lecture by Rabbi Dreyfus will be preceded by a brief ceremony. Four young playwrights —students or recent graduates of Chicago universities and colleges—will receive the Society’s Emerging Talent Awards for their one-act plays that received staged readings at the Chicago History Museum in connection with the “Shalom Chicago” exhibition.