Interpreting François Couperin's Pièces De Clavecin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8002-Cedille-On-The-Move-Booklet.Pdf

INTRODUCTION 1 JOHN ADAMS (b. 1946) I. Relaxed Groove from Road Movies (4:37) Cedille Records is devoted to promoting the finest musicians in and from Chicago by re- Jennifer Koh, violin leasing their efforts on high quality recordings. Our recording ideas come from the artists themselves, which is why we have such a widely varied catalog of innovatively programmed Reiko Uchida, piano recordings. From In 2004, Cedille released a sampler CD of calming compositions titled Serenely Cedille (Ce- String Poetic — dille Records CDR 8001). Now, five years later, we present a disc of high-energy selections st from our catalog, ideal for keeping you “on the move,” whether walking, running, biking, American Works: A 21 Century Perspective driving, exercising, or just enjoying the music’s rhythmic drive. The tracks run the gamut CDR 90000 103 from a Vivaldi flute concerto, to symphonic works by late-Classical era composers from Bohemia (Krommer and Voříšek), to (later) 19th century concertos and chamber works, to seven selections by contemporary or very recent composers. All feature propulsive rhyth- mic energy designed to keep the music (and you) moving forward. This is the piece that inspired the idea for this sampler CD. About it, the iconic American I hope you enjoy this disc, and that it inspires you to want to learn more about and hear composer writes, “Road Movies is travel music, music that is comfortably settled in a pulse more from the wonderful Chicago artists represented on this CD. Toward that end, the track groove and passes through harmonic and textural regions as one would pass through a listing in this booklet includes a short statement about each selection and its respective landscape on a car trip.” Although titled, “Relaxed Grove,” the opening movement conveys disc. -

Firlngllne Copyright University

rights other a All infringement. makes resale. for user a copyright not If for are liable material. be Copies may 94305-6010 user copyrighted prohibited. CA of is that use, New FIRlnGLlne This Transcripts 29205 HOST GUESTS FIRING Stanford, SUBJECT fair distribution of is reproductions York 8031799-3449 : a and further transcript LINE excess University, : other videocassettes : City in or and is , March "IS WILLIAM Stanford produced material. ROSALYN of reprints purposes a re GOOD this FIRING available for photocopies of 31, of Archives, and 1999, additional MUSIC through copies) re-use and Copyright F. LINE TURECK making directed BUCKLEY, any and Producers the Library program purposes; GOING telecast 1999 before handwritten by Inc and governs o FIRING WARREN rporated Institution owner SCHUYLER #2833/1200, UNDER?" JR. later educational Code) (including fo LINE and Hoover r on Television, U.S. copyright public University. 17, STEIBEL. the Jr. Director, taped CHAPIN reproduction 2700 (Title from television or Cypress Stanford contact at non-commercial, States HBO Street, permission photocopy Leland stations United private, a Columbia, Studios the for the obtain information, of is uses of to . SC later laws further in or material Trustees advised For of for, this are of copyright ©Board reserved. Users Use The request © Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. MR. BUCKLEY: Every few years Firing Line touches down on the question, Is classical music dying? We are lucky enough this time around to have got in to discuss the question two persons who have spoken to us before on the subject. One is perhaps the most distinguished pianist alive, the second, the senior man of music in New York City. -

Salon Musical Au Xviiie Siècle

Journées européennes du patrimoine Salon musical au XVIIIe siècle À l’écoute d’un mystérieux manuscrit de clavecin Samedi 14 septembre 2013 à 18h15 Archives des Yvelines Sommaire Programme p. 3 Le manuscrit p. 4 Les compositeurs p. 8 Un salon musical au XVIIIe siècle p. 10 Marie Vallin p. 11 Informations pratiques p.12 Concert donné à l’occasion des Journées européennes du patrimoine avec le concours du Conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Versailles et du Musée de la Toile de Jouy Conception et rédaction : Céline PAGNAC et Marie VALLIN - Conception graphique : Mathilde LAINEZ Ill. couverture, crédits : Archives des Yvelines Programme Jacques Duphly (1715-1789) La De Vatre La Félix La Lanza Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Pièce sans titre [Allegro] Allegro Anonyme L’orageuse Jean-Baptiste Barrière (1707-1747) Grave-Prestissimo, Allegro, Aria Domenico Alberti (v. 1710-1740) Allegro moderato (1er mouvement de la Sonate II) Anonyme Le réveil matin Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745) La Mandoline : M. Vallin 3 Crédit photo Le manuscrit Un document atypique May (avec violon), Menuet. Mais aux Archives d’autres pièces françaises sont aussi présentes : La Mandoline ux Archives des Yvelines se d’Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745), trouve, classé sous la cote A Les Ciclopes [sic] et la Pantomime 1F207, un recueil manuscrit de de Pigmalion [sic] du célèbre pièces de clavecin. Il suscite de Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764). nombreuses interrogations quant L’Italie est aussi représentée, avec à sa provenance, sa datation, au moins 5 sonates de Domenico son propriétaire. Il semble difficile Scarlatti (1685-1757), une sonate de remonter à ses origines : il n’est de Domenico Alberti (v. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

ARIANE GRAY HUBERT Concert Pianist, Singer & Composer Www

ARIANE GRAY HUBERT Concert Pianist, Singer & Composer www.arianegrayhubert.com A concert pianist, singer and composer, Ariane Gray Hubert is a much acclaimed and innovative artist in several fields. Over the years, she has delighted audiences and critics all over the world with her performances, be it a piano solo recital, a piano-vocal world music program or with various music ensembles. In her orchestral works, she blends both eastern and western music traditions in a unique manner—an absolutely visionary approach. Born in Paris with a French-American double nationality, the artist started her musical journey at the age of four. She was largely influenced by her American mother, Tamara Gray, and her great- aunt, who received her training from Alfred Cortot in Switzerland. The classical training Ariane Gray Hubert received is fascinating and ranged from the renowned Russian, Austrian and French piano traditions to the rich, oral music of the east. The distinctive characteristics of this French-American artist combine playing and singing together in expressive scales, her unique improvisation, powerful rhythmical ideas and inspiration from ancient musical traditions. In the west, the artist performs for major international festivals as well as for many productions in opera and dance. She played for Radio France, Musée d’Orsay, Opera Bastille & Garnier, the Vatican, the UNESCO, the European Delegation in India on the occasion of the 50 years of the EU Treaty, the French Alliances abroad (Austria, Germany, Italy, Baltic countries, India) and for various South American festivals. In 2010, in collaboration with various festivals abroad, she played “La Note Bleue” at the closing ceremony of the Festival “Bonjour India” to commemorate the bicentenary birth anniversary of F. -

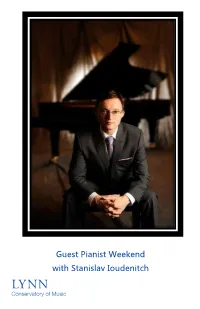

2016-2017 Master Class-Stanislav Ioudenitch

Guest Pianist Weekend with Stanislav Ioudenitch Pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch In Recital Saturday, Dec. 3 7:30 p.m. Count and Countess de Hoernle International Center Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall PROGRAM Spanish Rhapsody Franz Liszt Partita No. 2 in C minor JS Bach Sinfonia Allemande Courante Sarabande Rondeaux Capriccio Moment Musicaux Franz Schubert No. 3 Allegro moderato in F minor No. 4 Moderato in C-sharp minor Sonata No. 2 (1913 edition) Sergei Rachmaninoff Allegro agitato Non allegro Allegro molto Artist Biography STANISLAV IOUDENITCH has garnered notable successes in music competitions including the Gold Medal at the XI Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001. The Van Cliburn Competition launched a career that has taken Ioudenitch around the world for appearances with major venues, including Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, Fort the Moscow Conservatoire, Mariinsky Concert Hall, the Great Hall of the St Petersburg Philharmonic, the Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi in Milan, the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, the Oriental Art Center in Shanghai and appeared at major festivals including the International Piano Festival in the United States and the Ruhr Music Festival in Germany among others. Ioudenitch has collaborated with a wide range of international conductors including James Conlon, Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, Asher Fisch, Vladimir Spivakov, Günther Herbig, Pavel Kogan, James DePreist, Michael Stern, Stefan Sanderling, Carl St. Clair and Justus Frantz, and with such orchestras as the National Symphony in Washington DC, the Munich Philharmonic, Mariinsky Orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic, the National Philharmonic of Russia, the Fort Worth Symphony and the Kansas City Symphony among others. He has also performed with the Takács, Prazák and Borromeo String Quartets and is a founding member of the Park Piano Trio. -

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments and Its Intended Performance by Norah Drewett and the Hart House String Quartet

91 Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments and its intended performance by Norah Drewett and the Hart House String Quartet Marc-AndrC Roberge Abstract This article attempts to reconstruct the history of what was to be the first per- formance of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Quintet for Piano and Four Stringed Instruments (1919-20), which was scheduled to be given on 29 November 1925 at Aeolian Hall in New York by the pianist Norah Drewett and the University of Toronto's Hart House String Quartet as part of a concert sponsored by Edgard Varese's International Composers' Guild. The performance never took place for reasons that are not entirely clear but have to do mostly with the work's difficul- ties. The article also provides an introduction to the work itself, which Sorabji dedicated to his friend, the composer Philip Heseltine. Most people who have heard of Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988), the Parsi composer and pianist active who lived as a recluse in England for most of his career, know that performances of his often massive and extremely difficult works have been extremely rare as a result of a so-called ban.l The thirteen scores that Sorabji published between 1921 and 1931 contain the following warning: "All rights including that of performance, reserved for all countries by the composer." The score of his 248-page Opus clavicembalisticum (1929-30), his longest and most often cited work, contains the additional admonition: "Public performance prohibited unless by express consent of the composer." Various statements in letters make it possible to say that, in the late thirties, Sorabji had decided to turn down all requests for public performance either by himself or by others. -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF THE MAJOR PIANO WORKS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF By ANGELA GLOVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Angela Glover defended on April 8, 2003. ___________________________________ Professor James Streem Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Professor Janice Harsanyi Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Carolyn Bridger Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Thomas Wright Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….............................................. iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. MORCEAUX DE FANTAISIE, OP.3…………………………………………….. 3 2. MOMENTS MUSICAUX, OP.16……………………………………………….... 10 3. PRELUDES……………………………………………………………………….. 17 4. ETUDES-TABLEAUX…………………………………………………………… 36 5. SONATAS………………………………………………………………………… 51 6. VARIATIONS…………………………………………………………………….. 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………. -

Bach's Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations - A survey of the piano recordings by Ralph Moore Let me say right away that while I am well aware that Bach specified on the title page that these variations are for harpsichord, I much prefer them played on the modern piano in what is technically a transcription and venture to suggest that Bach would have loved the sonorities and flexibility of the modern instrument, even though it inevitably involves essentially faking the changes of register available on a double manual harpsichord. I hardly seem to be alone in this, in that, just as every great cellist wants to engage with the Cello Suites, so almost every great pianist seems to want to record his or her interpretation of the Goldbergs for posterity and the public appetite for recordings and performances on the pianoforte seems undiminished. I have accordingly confined this survey to that category; doubtless more authentic accounts on an original instrument have great merit but they lie beyond my scope, knowledge and experience; I have neither the acquaintance with, nor appreciation for, harpsichord versions to attempt a meaningful conspectus of them; nor, indeed, do I have the recording on my shelves and leave that task to a better-qualified reviewer. Here, however, is a good collective survey of the harpsichord recordings from The Classic Review aimed at the average punter like me. In common with many a devotee of this miraculous music, my own first encounter with it was via the second Glenn Gould recording when, many years ago, a cultivated girlfriend introduced me to it; it was love at first hearing (assisted, perhaps by my attachment to said lady, but that’s another story…). -

Du Clavecin À La Harpe

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS–SORBONNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE V « CONCEPTS ET LANGAGES » Patrimoines et langages musicaux CONSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUPÉRIEUR DE MUSIQUE ET DE DANSE DE PARIS THÈSE Pour l’obtention du grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ PARIS-SORBONNE Discipline / Spécialité : Musique Recherche et Pratique Présentée et soutenue par : Constance Luzzati Le 20 novembre 2014 Du clavecin à la harpe Transcription du répertoire français du XVIIIe siècle Sous la direction de : Madame Raphaëlle Legrand, professeur à l’université de Paris IV – Sorbonne Monsieur Kenneth Weiss, claveciniste, chef d’orchestre, professeur au CNSMDP JURY : Madame Violaine Anger, maître de conférence habilité à diriger des recherches à l’Université d’Evry-Val-d’Essonne Monsieur Jean-Pierre Bartoli, professeur à l’Université Paris IV – Sorbonne Monsieur Philippe Brandeis, directeur des études musicales et de la recherche au CNSMDP Madame Raphaëlle Legrand, professeur à l’Université Paris IV – Sorbonne Madame Isabelle Moretti, harpiste, professeur au CNSMDP Monsieur Bertrand Porot, professeur à l’Université de Reims Monsieur Kenneth Weiss, claveciniste, chef d’orchestre, professeur au CNSMDP 1 2 Le répertoire original pour harpe est relativement restreint. Deux voies permettent de concourir à son accroissement : la création contemporaine d’une part, et la transcription d’autre part. La présente étude interroge le rapport entre les habitus anciens et une pratique actuelle de transcription, depuis le répertoire de clavecin français du XVIIIe siècle vers la harpe. La transcription est ici considérée comme une pratique non notée qui relève de l’interprétation, et qui partage avec celle-ci, comme avec la traduction, des problématiques fondamentales en apparence antinomiques : esprit et lettre, idiomatisme et fidélité. -

Rosalyn Tureck Appointed Professor of Music

Rosalyn Tureck appointed Professor of Music May 17, 1966 Rosalyn Tureck, famed concert pianist and harpsichordist, has accepted appointment as Professor of Music at the University of California, San Diego it has been announced by University President Clark Kerr and San Diego Chancellor John S. Galbraith. Miss Tureck, one of the two or three outstanding proponents of baroque music in the world today, will join the faculty on July 1. She will teach in the newly formed Department of Music at Muir College, the second of 12 colleges planned for the UCSD campus. Muir College will accept its first students in the fall of 1967. In the meantime, Miss Tureck and the other members of the Muir College faculty will be engaged in the development of curriculum as well as teaching classes in the fine arts at Revelle College. Rosalyn Tureck is internationally acclaimed as "the greatest scholar and interpreter of Bach in the world today". She was born in Chicago where, at the age of 14, she was urged to specialize in Bach by her teacher, Jan Chiapusso. A year later she gave two all-Bach recitals in Chicago, and the following year, at the age of 16, won a full scholarship to the Juilliard School of Music in New York. She graduated cum laude with Life Fellowship from Juilliard in 1935 and immediately began a series of concert tours through the United States and Canada. Since 1947 her tours have been international taking her to England, Europe, Israel, South America and South Africa. In 1956, Miss Tureck began to conduct concerto and orchestral performances of Bach with the Collegium Musicum in Copenhagen. -

Why the Theremin Fell by the Wayside a Case Study in the Evolution of Paradigms in Music

Why the Theremin Fell By the Wayside A case study in the evolution of paradigms in music By: John Waymouth Sufficiency Course Sequence: Course Number Course Title Term HI1332 Introduction to the History of Technology A00 MU1611 Fundamentals of Music I A01 MU1612 Fundamentals of Music II B01 MU3611 Computer Techniques in Music C02 MU3612 Computers and Synthesizers in Music D02 Presented to: Professor Frederic Bianchi Department of Humanities and Arts Term B, 2004 Project FB-MU09 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of The Humanities and Arts Sufficiency Program Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester, Massachusetts Abstract The theremin was the first major electronic musical instrument. Play- ers cause the theremin to produce sound without contact at all by ma- nipulating electromagnetic fields with their hands. This unique design often sparks interest in those that learn about it, but despite this fact, the theremin has remained in relative obscurity since its invention. This paper discusses the history of the theremin and explains why it failed to gain widespread adoption, drawing on research in the growing field of memetics. i Contents 1 The Theremin 1 2 Background 2 2.1 The Invention ............................. 2 2.2 Clara Rockmore ........................... 4 2.3 Termen Returns to Russia ...................... 5 2.4 The Mid-Century ........................... 6 2.5 The Present Day ........................... 7 3 Why the Theremin Failed to Thrive 7 3.1 Interface Problems .......................... 8 3.2 Instruction .............................. 11 3.3 A Series of Unfortunate Events ................... 11 3.4 Memetics ............................... 12 3.4.1 Universal Darwinism ..................... 12 3.4.2 Techniques Memes Use .................... 14 3.4.3 Instrument Interfaces as Memes ..............