Globalisation, Hybridisation and the Finnishness of the Finnish Tango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tango Suomessa

108 KÄRJÄ & ÅBERG (toim.) - Tango Suomessa (toim.) - Tango & ÅBERG KÄRJÄ Tangomusiikki ilmiöineen on keskeinen osa suomalaista musiikkikulttuuria. Suomeen tango rantautui jo vuonna 1913, mutta varsinaiseen roihuun tango ilmiönä leimahti 1950- ja 1960-luvuilla. Suomalainen tango on leimautunut perinnekulttuuriksi, joka ei ole kuollut, vaikka sitä ajoittain onkin oltu valmiita hautaamaan: tuoreus on sen vahvuus. TANGO Tässä kirjassa joukko musiikintutkijoita lähestyy tangoa Suomessa useista näkökulmista: historiallisesta, kulttuuri- SUOMESSA sesta, musiikkianalyyttisestä, taloudellisesta ja paikallises- ANTTI-VILLE KÄRJÄ & KAI ÅBERG (TOIM.) ta. Näin kirja pyrkii luomaan kokonaisvaltaista kuvaa suomalaisesta tangokulttuurista ja sen sidoksista suomalai- suuteen. Kirja on ensimmäinen kokonaisvaltainen esitys aiheesta ja tarjoaa pohjan uusille ajatuksille sekä tangosta että Suomesta. Kirja on tarkoitettu kaikille suomalaisesta tangosta kiinnostuneille alan harrastajille ja ammattilaisille. ISBN 978-951-39-4673-9 9 789513 946739 NYKYKULTTUURIN TUTKIMUSKESKUKSEN JULKAISUJA 108 TANGO SUOMESSA NYKYKULTTUURIN TUTKIMUSKESKUKSEN JULKAISUJA 108 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO 2012 Copyright © tekijät ja Nykykulttuurin tutkimuskeskus Urpo Kovala (vastaava toimittaja, Jyväskylän yliopisto) Pekka Hassinen (toimitussihteeri, Jyväskylän yliopisto) Tuuli Lähdesmäki (toimitussihteeri, Jyväskylän yliopisto) Eoin Devereux (University of Limerick, Irlanti) Irma Hirsjärvi (Jyväskylän yliopisto) Kimmo Jokinen (Jyväskylän yliopisto) Anu Kantola (Helsingin yliopisto) Sanna -

Karaokelista Löytyy Aina Netistä : Laula.Se/2400 - Sivu 1 Jiipeen Karaoke

JIIPEEN KARAOKE Kappale Versio Levy Koodi 0 DVD KAPPALE ESITTAJA DVD 1000113 101 TAPAA OLLA VAPAA MAJ KARMA PR0 3427125 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT MEL 1002877 1963 15 VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS MEL 1004384 1972 ANSSI KELA MEL 1002889 2080-LUVULLA SANNI SAT 1315126 247 MIKKO SALMI MEL 1002952 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE MEL 1003839 A BIG HUNK OF LOVE ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315155 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315156 A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315157 A MESS OF BLUES ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315158 AALLOKKO KUTSUU GEORG MALMSTEN FIN 1295128 AAMU ANSSI KELA FIN 1294910 AAMU ANSSI KELA MEL 1003803 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG MEL 1003711 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG F12 1000218 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA F3 1000666 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA MEL 1002920 AAMU TOI ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN MEL 1003396 AAMU TOI ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN F8 1000821 AAMUKUUTEEN JENNA MEL 1003734 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN MEL 1002164 AAMUN KOI ESKO RAHKONEN TAT 1314228 AAMUN KOI ESKO RAHKONEN TAT 3402815 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA MEL 1003093 AAMUTÄHDEN AIKAAN EINI KOK 1315108 AAMUYHDEKSÄLTÄ POPULUKSEEN KAITA ISÄRI SEPPÄLÄ SK0 3425666 AAMUYÖ 101 MEL 1003856 AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI MEL 1314472 AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI SSK 3403162 AAMUÖISEEN SATEESEEN - EARLY MORNING RAIN... PAAVO JA ZEPHYR MEL 1002453 AAVEJUNA WILLIAM AJR KORWENKOSKI KAK 1311997 AAVEKAUPUNKI NIKO AHVONEN MEL 1002883 AAVERATSASTAJAT DANNY F20 1000482 AAVERATSASTAJAT JOHNNY CASH DANNY MEL 1003114 AAVERATSUT WILLIAM AJR KORWENKOSKI KAK 1314526 ADDICTED TO YOU LAURA VOUTILAINEN FIN 1294996 TULOSTETTU : 25.2.2020. AJANTASAINEN KARAOKELISTA LÖYTYY AINA NETISTÄ : LAULA.SE/2400 - SIVU 1 JIIPEEN KARAOKE ADIOS AMIGO LEA LAVEN FIN 1295197 ADIOS ROSARIO DINGO MEL 1314110 AFRIKKA SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI MEL 3403246 AHMAT TULEVAT HAPPORADIO PR0 3427126 AIGEIANMEREN LAULU PAULA KOIVUNIEMI MEL 1003642 AIGEIANMEREN LAULU TRAD. -

(Can't Start) Giving You up / Kylie Minogue

(BARRY) ISLANDS IN THE STREAM / COMIC RELIEF (305089) (CAN’T START) GIVING YOU UP / KYLIE MINOGUE (304339) 0 DVD KAPPALE / ESITTAJA (113) 1, 2 STEP / CIARA FEAT. MISSY ELLIOTT (304349) 10,000 NIGHTS / ALPHABEAT (311419) 100 PROCENT / LOTTA ENGBERG (7407) 12 APINAA / NYLON BEAT (1471) 12 APINAA / NYLON BEAT (2877) 17 FOREVER / METRO STATION (305144) 17 ÅR / VERONICA MAGGIO (7402) 1963 15 VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN / LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS (4384) 1972 / ANSSI KELA (2889) 1972 / ANSSI KELA (1496) 1985 / BOWLING FOR SOUP (304247) 2080-LUVULLA / SANNI (315126) 21 GUNS / GREEN DAY (305142) 21 QUESTIONS / 50 CENT FEAT.NATE DOGG (303986) 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN / GREEN DAY (305218) 22 / LILY ALLEN (305154) 247 / MIKKO SALMI (2952) 26AAMUYÖ / MERJA RASKI (314472) 3 (THREE) / BRITNEY SPEARS (305192) 3 WORDS / CHERYL COLE FEAT. WILL.I.AM (305222) 5 YEARS TIME / NOAH AND THE WHALE (304951) 50/50 / LEMAR (304084) 506 IKKUNAA / MILJOONASADE (3839) 7 MILAKLIV / MARTIN STENMARCK (314143) 7 THINGS / MILEY CYRUS (305021) 7 WAYS / ABS (311329) A BIG HUNK OF LOVE / ELVIS PRESLEY (315155) A FOOL SUCH AS I / ELVIS PRESLEY (315156) A HEADY TALE / THE FRATELLIS (305040) A LITTLE BIT / ROSIE RIBBONS (303893) A LITTLE BIT OF ACTION / NADIA (304287) A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION / ELVIS PRESLEY (315157) A MESS OF BLUES / ELVIS PRESLEY (315158) A-PUNK / VAMPIRE WEEKEND (305020) AAMU / ANSSI KELA (1833) AAMU / PEPE VILBERG (3711) AAMU / ANSSI KELA (3803) AAMU AIRISTOLLA / OLAVI VIRTA (2920) AAMU TOI ILTA VEI / JAMPPA TUOMINEN (3396) AAMUKUUTEEN / JENNA (3734) AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN / LEA LAVEN (2164) AAMUN KUISKAUS / STELLA (3093) AAMUTÄHDEN AIKAAN / EINI (315108) AAMUYÖ / 101 (3856) AAMUÖISEEN SATEESEEN-EARLY MORNING RAIN / PAAVO JA ZEPHYR (2453) AAVEKAUPUNKI / NIKO AHVONEN (2883) AAVERATSASTAJAT / JOHNNY CASH DANNY (3114) ABOUT A GIRL / SUGABABES (311432) ACAPELLA / KELIS (305293) ACAPULCO / ELVIS PRESLEY (312288) ADDICTED / ENRIQUE IGLESIAS (304086) ADIOS ROSARIO / DINGO (314110) AFRODISIAC / BRANDY (304253) AFTER YOU’RE GONE / ONE TRUE VOICE (303902) AFTERMATH / R.E.M. -

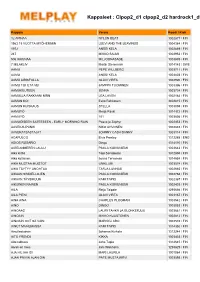

Clpop2 D1 Clpop2 D2 Hardrock1 D1 Hardrock1

Kappaleet : Clpop2_d1 clpop2_d2 hardrock1_d1 hardrock1_d2 kids_d1 kids_d2 mel_ladyoke2 mel01 mel02 mel03 mel04 mel05 mel06 mel07 mel08 mel09 mel10 mel11 mel12 mel13 mel14 mel15 mel16 mel17 mel18 mel19 mel20 mel21 mel22 mel23 mel24 mel25 mel26 mel27 mel28 mel29 mel30 mel31 mel32 mel33 mel34 mel35 mel36 mel37 mel38 mel39 mel40 mel41 mel42 mel43 mel44 mel45 mel46 mel47 mel48 mel49 mel50 mel51 mel52 mel53 mel53_2 Mel54 Mel54_a Mel54_b mel55 mel56 mel57 mel58 mel59 mel60 mel61 mel62 mel63 mel65 mel66 melclpop3_d1 melclpop3_d2 melElvis melfrank melganes melgospel meljoulu MelLadyoke melolaxtra melrockxtra melsixties melsvensk meltango sat01 sat02 sat03 sat04 sat05 sat06 sat07 sat08 sat09 sat10 sat11 sat12 sat13 tatsia14 tatsia16 tatsia23 tatsia24 tatsia5 tatsia9 valssi_a Kappale Versio Koodi / Kieli 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT 1002877 / FIN 1963 15 VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS 1004384 / FIN 1972 ANSSI KELA 1002889 / FIN 247 MIKKO SALMI 1002952 / FIN 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE 1003839 / FIN 7 MILAKLIV Martin Stenmarck 1314143 / SWE AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 1003711 / FIN AAMU ANSSI KELA 1003803 / FIN AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 1002920 / FIN AAMU TOI ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 1003396 / FIN AAMUKUUTEEN JENNA 1003734 / FIN AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 1002164 / FIN AAMUN KOI Esko Rahkonen 3402815 / FIN AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 1003093 / FIN AAMUYÖ Merja Raski 1314472 / FIN AAMUYÖ 101 1003856 / FIN AAMUÖISEEN SATEESEEN - EARLY MORNING RAIN Paavo ja Zephyr 1002453 / FIN AAVEKAUPUNKI NIKO AHVONEN 1002883 / FIN AAVERATSASTAJAT JOHNNY CASH DANNY 1003114 -

Käytä Ctrl+F Näppäintä Kappaleen Hakemiseen Listaltakappaleetkappaleet

Käytä Ctrl+F näppäintä kappaleen hakemiseen listaltakappaleetkappaleet KAPPALE ESITTÄJÄ CD Nr ALPPIMAAN ORAVAT KATRI HELENA LLP 1 ANNOIT MULLE MUISTON TARJA YLITALO LP 1 APUS KATRI HELENA LLP 1 ARKIHUOLESI KAIKKI HEITÄ LEE KIND JLP 1 BELLA CARA KIRSI RANTA LP 1 BELONGING TO NO ONE LOVEX NCD 1 BRAZIL FOXTET CD 1 DIFFERENT LIGHT LOVEX NCD 1 ELÄMÄNI PARHAINTA AIKAA MARKUS LP 1 END OF THE WORLD LOVEX NCD 1 END OF THE WORLD (OUTRO) LOVEX NCD 1 FELIZ NAVIDAD TRIO SALUDO JLP 1 HEINILLÄ HÄRKIEN KAUKALON TAPSA HEINONEN JLP 1 HIRMUHURJA SAMBATANSSI KATRI HELENA LLP 1 HYVÄSTI SELVÄ PÄIVÄ ARTO VIRTA LP 1 IF SHE'S NEAR LOVEX NCD 1 JOS VIELÄ OOT VAPAA FOXTET CD 1 JOULUN KELLOT MAIJA HAPUOJA JLP 1 JOULUPUKKI JOULUPUKKI PIRITTA JA LAPSIKUORO JLP 1 JOULUPUU ON RAKENNETTU LAPSIKUORO JLP 1 JOULUYÖ JUHLAYÖ TRIO SALUDO JLP 1 JUOKSE POROSEIN PIRITTA JLP 1 KAKARAKESTIT KATRI HELENA LLP 1 KERRO ETTÄ PALAAN ARTO NUOTIO LP 1 KESÄ LINNUT JA LAPSET KATRI HELENA LLP 1 KESÄINEN VALSSI FOXTET CD 1 KILIMANDZARO FOXTET CD 1 KILISEE KILISEE KULKUSET PIRITTA JA LAPSIKUORO JLP 1 KOSKA MEILLÄ ON JOULU PIRITTA JA LAPSIKUORO JLP 1 KREIKKALAINEN TANSSI FOXTET CD 1 KUKA ON TUO MIES MATTI JA TEPPO LP 1 KULKIJA FOXTET CD 1 KULKUSET RAUNI PEKKALA JLP 1 Käytä Ctrl+F näppäintä kappaleen hakemiseen listaltakappaleetkappaleet KUN JOULU ON MAIJA HAPUOJA JLP 1 KUNINGASKOOBRA KATRI HELENA LLP 1 LOVE AND LUST LOVEX NCD 1 LUOTAN SYDÄMEN ÄÄNEEN PIRJO SUOJANEN LP 1 LÄHTÖHETKI MATTI JA TEPPO LP 1 MATKAA TEEN FOXTET CD 1 MEREN RANNALLA FOXTET CD 1 MERKILLISTÄ KATRI HELENA LLP 1 MONTA MONTA -

KARAOKE on Demand

KARAOKE on demand Mood Media Finland Oy Äyritie 8 D, 01510 Vantaa, FINLAND Vaihde: 010 666 2230 Helpdesk: 010 666 2233 fi.all@ moodmedia.com www.moodmedia .fi FIN=FINNKARAOKE POW=POWER KARAOKE HEA=HEAVYKARAOKE Suomalaiset TÄH=KARAOKETÄHTI KSF=KSF FES=KARAOKE FESTIVAL KAPPALE ARTISTI ID TOIM 0010 APULANTA 700001 KSF 008 (HALLAA) APULANTA 700002 KSF 1972 ANSSI KELA 700003 POW 2080-LUVULLA SANNI 702735 FIN 5 LAISKAA AURINGOSSA PIENET MIEHET 702954 FIN 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE 702707 FIN A VOICE IN THE DARK TACERE 702514 HEA AALLOKKO KUTSUU GEORG MALMSTEN 700004 FIN AAMU ANSSI KELA 700005 FIN AAMU ANSSI KELA 701943 TÄH AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 700006 FIN AAMU PEPE WILLBERG 701944 TÄH AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA 700007 FIN AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 700008 FIN AAMU TOI, ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN 701945 TÄH AAMUISIN ZEN CAFE 701946 TÄH AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN 701947 TÄH AAMULLA VARHAIN KANSANLAULU 701948 TÄH AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA 700009 POW AAMUUN ON HETKI AIKAA CHARLES PLOGMAN 700010 POW AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI 701949 TÄH AAVA EDEA 701950 TÄH AAVERATSASTAJAT DANNY 700011 FIN ADDICTED TO YOU LAURA VOUTILAINEN 700012 FIN ADIOS AMIGO LEA LAVEN 700013 FIN AFRIKKA, SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI 700014 POW AI AI AI JA VOI VOI VOI IRWIN GOODMAN 702920 FIN AI AI JUSSI TUIJA MARIA 700015 POW AIKA NÄYTTÄÄ JUKKA KUOPPAMÄKI 700016 FIN AIKAAN SINIKELLOJEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700017 FIN AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700018 FIN AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 700019 POW AIKUINEN NAINEN PAULA KOIVUNIEMI 701951 TÄH AILA REIJO TAIPALE 700020 FIN AINA -

Foreign Issues: the National and International in 1960S Finnish Popular Music Discourse

journal of interdisciplinary music studies spring 2007, volume 1, issue 1, art. #071103, pp. 51-62 Foreign Issues: The National and International in 1960s Finnish Popular Music Discourse Harici Meseleler: 1960’lardaki Fin Popüler Müzik Söyleminde Ulusal ve Uluslararası Janne Mäkelä Renvall Institute for Area and Cultural Studies, University of Helsinki Abstract. The 1950s and early 1960s are often Özet. 1950’ler ve 1960’ların baı, çounlukla, understood as a golden era of popular music in Finlandiya’da popüler müziin altın çaı Finland. Forms of light entertainment music olarak düünülür. Listelere egemen olan hafif that dominated the charts have been consid- elence müzii yerel ve ulusal kimlikleri yo- ered as cultural expressions deeply reflecting un biçimde yansıtan kültürel ifadeler olarak local and national identities. At the same time, deerlendirilmitir. Aynı zamanda rock’n’roll, new styles invaded Finland, such as Latin tartımları, talyan elence müzii ve rock’n’roll, Latin rhythms, Italian entertain- sonraki dönemlerde de belirli düzeyde pop ve ment music and somewhat later pop and rock, rock gibi yeni biçemler müzik üretimini et- influencing music production and indicating a kileyip ülke dıı müzik biçem ve kültürlerine new kind of mass appeal for non-domestic karı yeni tür bir kitlesel talebin göstergesi music styles and cultures. Instead of retelling olarak Finlandiya’yı istila etmitir. Bu makale, the triumph of Finnish light entertainment son yirmi yıl boyunca Finli müzik tarihçi- music, iskelmä (schlager), or mapping the lerinin tipik olarak yaptıı gibi Fin hafif foreign influences - tasks that have been typi- elence müzii iskelma’nın (schlager) zafe- cal of Finnish music historians during the past rinin yeniden anlatılması ya da yabancı etki- twenty years - this paper deals with how the lerin bir haritasının çıkarılmasından ziyade notions of national and international were ulusal ve uluslararası nosyonlarının popüler construed in popular music and the discussions müzik ve onu çevreleyen tartımalarda nasıl surrounding it. -

FAZERIN MUSIIKKIKAUPPA Asfalttikukka Ja Emma

FAZER FAZERIN MUSIIKKIKAUPPA Konrad Georg Fazerin vuonna 1897 Helsinkiin perustama Fazerin Musiikkikauppa tuli mu- kaan äänilevyalalle vuonna 1910. Se oli silloin jo menestyvä musiikkiliike, jolla oli haaraliikkeitä muualla maassa. Tärkeimpiä artikkeleita olivat soittimet ja nuotit, mutta gramofonit ja äänilevyt olivat kiinnostava uusi tuote. Englantilaisella Gramophone-yhtiöllä oli ollut Suomessa edustus jo vuodesta 1903, mutta yhtiö oli tyytymätön entisen agenttinsa tuloksiin, ja edustus siirrettiin Fazerille. (Seuraavassa puhumme yksinkertaisuuden vuoksi Fazerista, kun tarkoitamme Fazerin Musiikkikauppaa. Sitä ei tietenkään pidä sekoittaa Fazerin makeistehtaaseen, jonka perustaja oli Karl Fazer, Konradin veli. Sekaannuksen välttämiseksi alalla toimineet ihmiset puhuivat aika- naan ”Musiikki-Fazerista” ja ”Karamelli-Fazerista”). Fazerin ensimmäinen äänilevytähti oli J. Alfred Tanner, joka oli juuri tehnyt läpimurron helsinkiläisessä revyyteatterissa. Fazer ja Gramophone hallitsivatkin ennen ensimmäistä maa- ilmansotaa lähes totaalisesti Suomen pieniä markkinoita, mutta sitten suomalaisten levyjen tuotanto katkesi lähes kymmeneksi vuodeksi. Nuorella tasavallalla oli muutakin mietittävää. Asfalttikukka ja Emma Vuonna 1925 olot olivat vakiintuneet jo niin paljon, että Fazer saattoi jälleen lähettää taiteilijoita levyttämään ulkomaille. Yhteystyökumppani oli edelleen Gramophone, mutta levymerkiksi oli muuttunut His Master’s Voice. Levymyynti kääntyi todella nousuun vasta vuon- na 1929, jolloin äänilevyjen tuontitulleja alennettiin. Suurimpana -

Sing Music Karaoke - Kappalejärjestys

Sing Music Karaoke - kappalejärjestys Kappale Versio Levy Koodi 12 APINAA NYLON BEAT MEL 1002877 1963 15 VUOTTA MYÖHEMMIN LEEVI AND THE LEAVINGS MEL 1004384 1972 ANSSI KELA MEL 1002889 2080-LUVULLA SANNI SAT 1315126 247 MIKKO SALMI MEL 1002952 506 IKKUNAA MILJOONASADE MEL 1003839 7 MILAKLIV MARTIN STENMARCK MEL 1314143 9 TO 5 DOLLY PARTON PCK 1004740 A BIG HUNK OF LOVE ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315155 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS PCK 1004671 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315156 A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315157 A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION ELVIS PRESLEY PCK 1007088 A MESS OF BLUES ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1315158 A MOMENT LIKE THIS4.28 LEONA LEWIS PCK 1007331 A VIEW TO A KILL DURAN DURAN PCK 1004829 AAMU ANSSI KELA MEL 1003803 AAMU PEPE WILLBERG MEL 1003711 AAMU AIRISTOLLA OLAVI VIRTA MEL 1002920 AAMU TOI ILTA VEI JAMPPA TUOMINEN MEL 1003396 AAMUKUUTEEN JENNA MEL 1003734 AAMULLA RAKKAANI NÄIN LEA LAVEN MEL 1002164 AAMULLA VARHAIN TRAD. KAS 3403344 AAMUN KOI ESKO RAHKONEN TAT 1314228 AAMUN KOI ESKO RAHKONEN TAT 3402815 AAMUN KUISKAUS STELLA MEL 1003093 AAMUYHDEKSÄLTÄ POPULUKSEEN KAITA ISÄRI SEPPÄLÄ SK0 3425666 AAMUYÖ 101 MEL 1003856 AAMUYÖ MERJA RASKI MEL 1314472 AAMUÖISEEN SATEESEEN - EARLY MORNINGPAAVO RAIN JA ZEPHYR MEL 1002453 AAVEKAUPUNKI NIKO AHVONEN MEL 1002883 AAVERATSASTAJAT JOHNNY CASH DANNY MEL 1003114 ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS DAVID BOWIE PCK 1004662 ACAPULCO ELVIS PRESLEY MEL 1312288 ADIOS ROSARIO DINGO MEL 1314110 AFRIKKA SARVIKUONOJEN MAA EPPU NORMAALI MEL 3403246 AFTER ALL CHER AND PETER CETERA PCK 1007062 AH MARIA ITALIAN -

El Motivo Revisited; Sä Et Kyyneltä Nää; Loca Bohemia; and Tango Desirée Were Recorded at Kulosaari Church, Helsinki, Finland on August 8, 2012

Acknowledgments E l M o t i v o El Choclo; El Marne; and all the phonies go mad with joy; Nocturna; Trois tangos en marge; Tengo miedo; and el jefe were recorded at P a b l o o r t i z | a nssi Karttunen The Banff Center, Canada, February 21-22, 2011. Recording engineer: Cain McCormack Recording producer: Hazel Burns Nostalgias; El Marne; Sateen tango; En Cada Verso; El Motivo revisited; Sä et kyyneltä nää; Loca Bohemia; and Tango Desirée were recorded at Kulosaari Church, Helsinki, Finland on August 8, 2012. Recording engineer: Matti Heinonen (Pro Audile) Editing: Anssi Karttunen All works by Pablo Ortiz are published by Argofelipix. Arrangements by Pablo Ortiz and Anssi Karttunen are available direct from the arrangers. Cover Image: Helsinki 1973 © Pentti Sammallahti Artist photos: Zebra Trio: © Kaija Saariaho, cellists: © Hanno Karttunen www.albanyrecords.com TROY1421 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 Z e b r a T r i o albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd a n s s i K a r tt unen Timo-Vei kk o V a l V e J u s s i s e p p ä n e n tel: 01539 824008 © 2013 albany records made in the usa ddd c e l l o s waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. El Motivo There are two versions of Eduardo Arolas’s El Marne on this CD. In the first one, for It all started in 2000 in Davis, California, when Pablo Ortiz played me a recording of String Trio, I was inspired by a recording by Ciriaco Ortiz and a little also by Horacio improvisations by Aníbal Troilo and Astor Piazzolla on Volver and El Motivo. -

Täynnä Tapahtumia Teeming with Events

LA-MA 14.-16.9. BLUE MAN GROUP TAMPERE-TALO TÄYNNÄ TAPAHTUMIA SYKSYLLÄ 2019 TAMPERE HALL IS TEEMING WITH EVENTS IN AUTUMN 2019 LIIKUTU JA RIEMASTU LET TAMPERE HALL MOVE ELÄMYSTEN TALOSSA AND ENTHRALL YOU Tampere-talo jatkaa huimaa tahtiaan ja marssittaa Tampere Hall continues to offer premium events in the saleihinsa toinen toistaan makeampia, suurempia, spring, filling its venue with the sweetest, grandest and ikimuistoisempia ja toisaalta intiimimpiä ja herkimpiä most memorable events in town, without forgetting tapahtumia. Laajalla skaalalla riemua, liikutusta the more intimate small-scale performances. A wide ja elämyksiä tarjoavat useat kansainväliset ja array of joy, emotion and experiences, brought to you kotimaiset tähdet, taiteenalojen rajoja ylittävä by the brightest Finnish and international stars, cross- monikerroksellinen kulttuuri ja huimat iskelmä-, pop-, disciplinary and multi-layered cultural performances, the rock- ja klassikkohelmet unohtamatta valtoimenaan gems of Finnish schlager, pop, rock and classics with a kukkivaa huumoria! healthy amount of humour. Ovet ovat auki – kutsumme sinut osaksi taloamme! The doors are open, come on in and enjoy the show! JOKO SINULLE TULEE ALREADY SUBSCRIBED TO TAMPERE-TALON UUTISKIRJE? TAMPERE HALL'S NEWSLETTER? Uutiskirjeen tilaajana saat tietoa konserteista ja Our newsletter gives you first-hand information tapahtumista ensimmäisenä sekä alennuksia, on upcoming concerts, events campaigns, etuja ja tarjouksia. benefits and offers. Tilaa täältä: TAMPERE-TALO.FI Subscribe here: TAMPERE-TALO.FI SEURAA MEITÄ SOMESSA FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA Sukella tunnelmalliseen ja Dive into the atmosphere and events tapahtumarikkaaseen Tampere-taloon of Tampere Hall on Facebook, Twitter, Facebookissa, Instagramissa, Twitterissä ja Instagram and LinkedIn. LinkedInissä. @TAMPEREHALL @TAMPERETALO Tähdellä merkityissä tilaisuuksissa ovat voimassa Tampere-talon Loyal customer benefits are available kanta-asiakasedut. -

Cash Box—September 3, 1960 5 1 the Cash Box Best Selling Monaural & Stereo Albums

VOLUME XXI-NUMBER 51 SEPTEMBER 3. 1960 While listening to a playback of his latest release, Roy Orbison coincidentally strikes a lonely pose that ties in well with his current smash single “Only The Lonely.” The Monument songster, who had shown great promise with many of his past recordings, made his first move on the charts with “Uptown” earlier in the year. Now “Only The Lonely” has established him as one of the leading newcom- ers on wax. Orbison is a twin threat, writing as well as recording hit songs. He penned “Only The Lonely” and is co-author of his latest single “Blue Angel” which has just been released with “Today’s Teardrops” as the coupling. Monument Rec- ords is distributed through the London Record Company. BURTON MANAGEMENT INC The Cash Box—September 3, 1960 5 1 The Cash Box Best Selling Monaural & Stereo Albums COMPILED BY The Cash Box FROM LEADING RETAIL OUTLETS ' .::lllllllllllllllllllllilllll ; Tllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllillllllllllililllillllllllllli MONRURRL • Also available in Stereo Also available in EP STEREO Pos. Last Pov Lost Pos. Lobt Pos. Lost > Week Week Week Week STRING ALONG 2 JACKIE SINGS THE STRING ALONG 2 THE BUTTON DOWN MIND -^e e A1 1 Kingston Trio (Capitol T 1407; 26 BLUES 21 Kingston Trio (Capitol 5T-1407) 26 OF BOB NEWHART 25 ST 1407 *;^,3/407; Jackie Wilson Bob Newhart (Brunsvrick BL-S40SS; BL 7-54055; (Warner Bros. WS 1379) e THE BUTTON DOWN 0 PERSUASIVE PERCUSSION 1 BEN HUR 23 L Terry Snyder (Command S-800) 2 MIND OF BOB e FAITHFULLY 27 27 Sound Track 1 Johnny Mathis (Columbia NEWHART (MGM lEI; ISEI) 27 CS 8219) (Warner Bros.