Fall 2018, Volume 37.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix B NEPA Process

APPENDIX B SUMMARY OF NEPA PROCESS FOR WMRNP WEST MOJAVE (WEMO) ROUTE NETWORK PROJECT SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Appendix B Summary of NEPA Process for WMRNP B.1 Notice of Intent The impact analyses are based on the Applicant’s description of their proposed Project, and that description includes, for some The planning process was initiated by a Notice of Intent (NOI) to prepare a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Plan Amendment to the 2006 WEMO Plan that was published in the Federal Register on September 13, 2011, and clarified on May 2, 2013. The clarified NOI served as notification of the intent to prepare an EIS as required in 40 CFR 1501.7, as well as of potential amendment to the CDCA Plan. The NOI served to indicate the planning- level vs non-planning level decisions, and to clarify that the plan amendment would be an EIS- level amendment, and requested comments on relevant issues, National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) (16 U.S.C. 470(f) concerns, and initial planning criteria for the plan amendment. The NOI indicated that the Proposed Plan Amendment and SEIS would consider the following: Amend the Motorized-Vehicle Access (MVA) Element of the CDCA Plan to modify the language regarding the process for designating routes in the West Mojave Planning Area; Reconsider other MVA Element land-use-planning level guidance for the West Mojave Planning Area; Revisit the route designation process for the West Mojave Planning Area; Clarify the West Mojave Planning Area inventory for route designation and analysis; Establish a route network in the Planning Area consistent with current guidance and new information; Adopt travel management areas (TMAs) to facilitate implementation of the West Mojave route network; Provide or modify network-wide and TMA-specific activity-plan level minimization, mitigation, and other implementation strategies for the West Mojave Planning Area; and Respond to specific issues related to the US District Court WEMO Summary Judgment and Remedy Orders. -

WMRNP Final SEIS LUPA Appendix B NEPA Process

APPENDIX B SUMMARY OF NEPA PROCESS FOR WMRNP WEST MOJAVE (WEMO) ROUTE NETWORK PROJECT SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Appendix B Summary of NEPA Process for WMRNP B.1 Notice of Intent The impact analyses are based on the Applicant’s description of their proposed Project, and that description includes, for some The planning process was initiated by a Notice of Intent (NOI) to prepare a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Plan Amendment to the 2006 WEMO Plan that was published in the Federal Register on September 13, 2011, and clarified on May 2, 2013. The clarified NOI served as notification of the intent to prepare an EIS as required in 40 CFR 1501.7, as well as of potential amendment to the CDCA Plan. The NOI served to indicate the planning- level vs non-planning level decisions, and to clarify that the plan amendment would be an EIS- level amendment, and requested comments on relevant issues, National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) (16 U.S.C. 470(f) concerns, and initial planning criteria for the plan amendment. The NOI indicated that the Proposed Plan Amendment and SEIS would consider the following: Amend the Motorized-Vehicle Access (MVA) Element of the CDCA Plan to modify the language regarding the process for designating routes in the West Mojave Planning Area; Reconsider other MVA Element land-use-planning level guidance for the West Mojave Planning Area; Revisit the route designation process for the West Mojave Planning Area; Clarify the West Mojave Planning Area inventory for route designation and analysis; Establish a route network in the Planning Area consistent with current guidance and new information; Adopt travel management areas (TMAs) to facilitate implementation of the West Mojave route network; Provide or modify network-wide and TMA-specific activity-plan level minimization, mitigation, and other implementation strategies for the West Mojave Planning Area; and Respond to specific issues related to the US District Court WEMO Summary Judgment and Remedy Orders. -

Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS – Appendix L

El Paso/ Rands Special Recreation Management Area (SRMA) RMA/RECREATION MANAGEMENT ZONE (RMZ) OBJECTIVE(S) DECISIONS Background: The El Paso Rands SRMA consists of 3 separate Recreation Management Zones (RMZ’s) - El Paso Mountains, Rand Mountains Management Area, and Desert Tortoise Research Natural Area. These separate areas provide multiple use recreation opportunities that stretch from the northern side of California City, heading north up through the Desert Tortoise Natural Area, connecting through Rand Mountains Management Area, and ending up on the southern boundary of Inyokern California. From east to west, the El Paso Rands SRMA is sandwiched between State Highway 14 and U.S. Highway 395. These paved highways provide several ways to access these areas with multiple routes waiting for users to experience all its glorious landscapes and attractions. Recreational enthusiasts from Southern and Central California especially flock to this area each year between the months of October and May to take a trip back in time to explore the left over remnants of a society’s addiction to gold in 1895. One of the main attractions today is the “living” ghost town of Ransburg. It is known as the living ghost town due to the fact that some of the businesses are still open with a small population living in their houses that were built back in its prime. Friends and family that recreate and camp in the local area navigate to Randsburg for lunch while touring the rest of the RMZ’s. On the major holiday weekends approximately 2000 users with their off-highway vehicle are dispersed over the town visiting the open businesses and bringing in revenue to the historic town. -

East Kern Visions Burro Schmidt’S Tunnel: a Study in Perseverance by CHERYL MCDONALD Other Side of the Mountains

Spotlight: Whiskey Flat and the Kern River area EEaasstt KKeeJanrurarynn 2015 VViissiioonnss Furnace Creek getaway Bakersfield Condors hockey Burro Schmidt’s tunnel EEaasstt KKeeJanrurarynn 2015 VViissiioonnss Publisher John Watkins Inside this issue Editor Burro Schmidt’s Tunnel .....................3 Whiskey Flat Days events ...............10 Aaron Crutchfield Bakersfield Condors ..........................4 California City 50th anniversary ......11 Tierra Del Sol Golf Course ................5 Furnace Creek ..................................12 Advertising Director Paula McKay Whiskey Flat Days .............................7 Movie extra casting agency .............13 Ewings on the Kern ...........................9 Upcoming theater productions .......15 Advertising Sales Rodney Preul Barbara Schultheiss On tthe cover:: The Kern Riiver,, by Wiikiimeddiiaa CCoommmmonnss uusseer Rasttrojjo Writers Cheryl McDonald Ryan Kuhn Joyce Grant Aaron Crutchfield Jessica Weston Adam Robertson For this issue, we take a look at the major festival that is Whiskey Flat Days in Kernville. We also feature restaurant Ewing’s on the Kern, a local institution that recently reopened. 2 JAnuAry 2015 EASt KErn VISIonS Burro Schmidt’s tunnel: A study in perseverance BY CHERYL MCDONALD other side of the mountains. Unfortu - For the Daily Independent nately, it took him 32 years to complete the tunnel, and by then there were faster I was flipping through the channels forms of transportation. However, dig - the other evening, on my way to the ging this half-mile tunnel probably saved News Hour, and I came across an his life. He lived to the ripe old age of 81, episode of Huell Howser’s California dying just a few days before his 82nd Gold. It was his episode on the “Califor - birthday. nia Underground.” The last half of the William got his nickname of “Burro” show was just beginning, and guess who because his only companions were two PHOTO BY CHERYL MCDONALD was on the agenda: Burro Schmidt and burros he used for hauling supplies. -

Environmental Impact Statement

APPENDIX A SCOPING REPORT WEST MOJAVE ROUTE NETWORK PROJECT Scoping Report U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan De Los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 June 2012 This page intentionally left blank. Scoping Report Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose and Need for the West Mojave Route Network Project ......................................... 5 1.2 Planning Criteria ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Scoping Process .....................................................................................................................6 2.1 Purpose of Public and Agency Seeping .................................................................................. 6 2.2 Seeping Framework and Agency Consultation ................... .. ................................................. 6 2.3 Purpose of Seeping Report ..................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Notification and Seeping Meeting Advertisements ............................................................... 7 2.5 Seeping Meetings ................................................................................................................... 7 3.0 Scoping Comments ............................................................................................................. -

Admin Draft WEMO Appendix B WEMO Subregion

APPENDIX B SUBREGION DESCRIPTIONS WEST MOJAVE (WEMO) ROUTE NETWORK PROJECT SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT APPENDIX B WEST MOJAVE TRAVEL MANAGEMENT AREAS AND SUBREGIONS Introduction One of the first steps in the off-road vehicle designation process was the identification of travel management areas (TMA) for travel network. Eight travel management areas provide the geographical framework for implementation of the travel network through specific transportation and travel management (TTM) plans. The factors used in the development of boundaries for TMA are primarily natural transportation boundaries (e.g. highways, jurisdictional, geographic boundaries). Because of the size of the West Mojave (WEMO) Planning area, the eight TMA were further subdivided into 36 Subregions. The boundaries of the 36 Subregions that compose the TMA consider the natural transportation boundaries, law enforcement patrol areas, designated management areas, and issue-driven factors. By comparison, the 2006 WEMO Plan had identified 20 different Subregions, which included much but not all of the West Mojave Planning area, from which they examined 11 subregions to build the WEMO network. The 2006 WEMO Subregions are based on similarities in certain biological characteristics but do not readily lend themselves to on-the-ground implementation of the transportation network. The 2006 WEMO Subregion boundaries roughly correlate to the new Subregion boundaries as feasible. The following discussion provides a general overview of each of the Travel Management Areas and the Subregions within it. B.1 Travel Management Area (TMA) 1 Afton Canyon Subregion The Afton Canyon Subregion comprises the northeastern third of TMA 1, extending south from Interstate 15 to include both the Afton Canyon ACEC and the northern two-thirds of the Cady Mountains Wilderness Study Area. -

Complete HAT Awards Guide

HIGH ADVENTURE AWARDS FOR SCOUTS AND VENTURERS 2016 HIGH ADVENTURE AWARDS SCOUTS & VENTURES BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA - WESTERN REGION AUGUST 2019 CHAPTER 1 ORANGE COUNTY AWARD/PROGRAM ACTIVITY AREA AWARD PAGE 3 SAINTS AWARD ANY APPROVED WILDERNESS AREA PATCH 1-12 BACKCOUNTRY LEADERSHIP ANY APPROVED WILDERNESS AREA PATCH 1-4 BOY SCOUT TRAIL BOY SCOUT TRAIL PATCH 1-7 BRON DRAGANOV HONOR AWARD ANYWHERE PATCH 1-17 BSA ROCKETEER SANCTIONED CLUB LAUNCH PATCH 1-19 CHANNEL ISLANDS ADVENTURER CHANNEL ISLANDS PATCH 1-6 CHRISTMAS CONSERVATION CORP ANYWHERE PATCH 1-22 DEATH VALLEY CYCLING 50 MILER DEATH VALLEY PATCH 1-6 EAGLE SCOUT LEADERSHIP SERVICE ANYWHERE PATCH 1-2 EAGLE SCOUT PEAK EAGLE SCOUT PEAK PATCH 1-13 EAGLE SCOUT PEAK POCKET PATCH EAGLE SCOUT PEAK PATCH 1-13 EASTER BREAK SCIENCE TREK ANYWHERE PATCH 1-20 HAT OUTSTANDING SERVICE AWARD SPECIAL PATCH 1-16 HIGH LOW AWARD MT. WHITNEY/DEATH VALLEY PATCH 1-5 JOHN MUIR TRAIL THROUGH TREK JOHN MUIR TRAIL MEDAL 1-15 MARINE AREA EAGLE PROJECT MARINE PROTECTED AREA PATCH 1-8 MT WHITNEY DAY TREK MOUNT WHITNEY PATCH 1-9 NOTHING PEAKBAGGER AWARD ANYWHERE PATCH 1-14 SEVEN LEAGUE BOOT ANYWHERE PATCH 1-3 MILES SEGMENTS ANYWHERE SEGMENT 1-3 SANTIAGO PEAK AWARD SANTIAGO PEAK PATVH 1-9 TELESCOPE PEAK DAY TREK TELESCOPE PEAK PATCH 1-10 THREE DAY BACKPACK ANYWHERE PATCH 1-2 TOP ROPING HONOR AWARD JOSHUA TREE NATIONAL MONUMENT PATCH 1-1 TRANS CATALINA BACKPACK AWARD CATALINA ISLAND PATCH 1-22 WHITE MOUNTAIN WHITE MOUNTAIN PATCH 1-11 WILDERNESS SLOT CANYONEERING SLOT CANYON SEGMENTS PATCH 1-18 ESCALANTE CANYONEERING -

Soda Mountain Solar Project Public Scoping Report EIS/EIR

PUBLIC SCOPING REPORT Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report Soda Mountain Solar Project Lead Agencies: Bureau of Land Management Contact: Jeffery Childers, 951-697-5308 22835 Calle San Juan De Los Lagos Moreno Valley, California 92553-9046 San Bernardino County Contact: Nelson Miller, (760) 995-8153 15900 Smoke Tree Street Hesperia, CA 92345 JANUARY 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Soda Mountain Solar Project Public Scoping Report EIS/EIR Page Acronyms Used in this Report iii 1.0 Overview of NEPA/CEQA Scoping Process 1-1 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 Summary of NEPA/CEQA Scoping Process 1-2 1.3 Agencies, Organizations, and Persons Providing Scoping Comments 1-3 1.4 Scoping Report Organization 1-3 2.0 Summary of the Proposed Project 2-1 2.1 The BLM’s Purpose and Need 2-1 2.2 Applicant’s Project Objectives 2-1 2.3 Project Description 2-2 3.0 Summary of Scoping Comments 3-1 3.1 Project Description 3-1 3.2 Human Environment Issues 3-2 3.3 Natural Environment Issues 3-7 3.4 Cumulative Impacts 3-21 3.5 Project Alternatives 3-22 3.6 EIS/EIR Administrative and Permitting Issues 3-24 3.7 Issues Outside the Scope of the EIS/EIR 3-24 4.0 Summary of Future Steps in the Planning Process 4-1 Appendices A. Notices A-1 A-1 Notice of Intent (published in the Federal Register on October 23, 2012) A-2 Notice of Preparation (posted October 26, 2012) B. Public Notices B-1 B-1 Scoping Meeting Announcement C. -

View Document

California Off-Road Vehicle Association 1500 W El Camino Ave. #352· Sacramento · California · 95833-1945 Phone · 916-710-1950· [email protected] · www.corva.org Red Rock State Park Issues of Concern The following comments are based on the Preliminary Planning Concepts for the Red Rock State Park General Plan Revision that were first provided at the March 26 and 27, 2019 public meetings (Concepts document). We understand that Concepts #1-4 are preliminary, however they are not accompanied by enough resource information for the reader to provide informed comments on these concepts. In addition, the maps on which the concepts are based are incomplete and do not reflect the actual existing condition of the transportation system as depicted on Red Rock Canyon State Park maps (attached). We greatly appreciate the extension of the comment period. This has provided time for us to perform additional field work with the assistance of Parks staff, which was especially fruitful. We have also been able to locate supplemental material that has helped inform our comments. Unfortunately, much of this material is taken from previous plan revision efforts in 2002-2003 and 2008-2009, so the information is dated and does not include any additional surveys undertaken since that time. We look forward to receiving more complete surveys and information as the planning process moves along, and our comments will be revised accordingly. Since CORVA is an off-road vehicle organization that represents the interests of our members, our comments are formed using that perspective. However, we have approached this project with the understanding that Red Rock Canyon is a State Park with a mission that is different from an SVRA, and that non-SVRA state parks are operated under a mandate that emphasizes resource protection as a greater priority than off-road vehicle use. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

Stargazers Dream chasers Visit and the High Desert and the High Ridgecrest Trailblazers 2 2016 RACVB Visitors Guide 2016 RACVB Visitors Guide 3 Welcome to California’s beautiful deserts Hello friends, thank you for your interest in visiting our beautiful desert. Many tourists have never experi- enced the deserts on the eastern sides of the Sierra. Visitors will find activities for all interests, and attractions to fit any theme – geological landmarks, outdoor sports, museums, wildlife, ghost towns, California history, stargazing and more. Increasingly popular among eco-tourists, the California high desert is home to exotic plant and animal life. The alien terrain is a hot spot for geo-caching, off-roading, and rock climbing. Hike the famous Pacific Crest Trail, John Muir Trail, and Mount Whitney. Cosmic enthusiasts seek out our high elevation and protected horizon for the most incredible star-gazing in California year round. We hope your visit is both exciting and comfortable. The city of Ridgecrest has 18 hotels and 65 restaurants to choose from. Nestled at the crossroads of three major highways and only 3 hours away from • Death Valley National Park •Disneyland • Yosemite National Park • Paso Robles wine country • Mammoth Mountain ski resort • Los Angeles • Las Vegas Whether you are looking for some peace and quiet, a new place to call home or are just passing through, we have what you need to make the most of your desert experience. Doug Lueck Executive Director, RACVB Table of Contents Museums 6 Membership Directory 22 Petroglyph -

Off-Roaders in Action Spring 2018

Off-Roaders in Action Spring 2018 2 President’s Annual Report 2018 11 CORVA 2017 Annual Awards 3 Managing Director’s Report 12 CORVA Store New Items! 4 Land Use Report 13 Red Rock and Jawbone Canyon 6 An Open Letter to Senator Glazer 13 Truckhaven Challenge 2019 7 Locked Gates Ahead 14 44th Annual High Desert Rally 9 The Ongoing Oceano Dunes Travesty 16 Red Rock and Jawbone Canyon 10 CORVA Election Results 17 Chad and Gizmo 10 Meet Wayne Ford 18 Pismo Dunes Settlement 10 Meet Charles Lowe 22 Eastern Sierra 4WD Club Earth Day 11 Meet Vinnie Barbarino DEDICATED TO PROTECTING OUR LANDS FOR THE PEOPLE, NOT FROM THE PEOPLE. PRESIDENT'S ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Ken Clarke, President It’s been a year since I was elected President of 70+ years. Now are faced with neighbors and the CORVA and I am eagerly looking forward to this next San Luis Obispo Air Pollution Control District Hearing year. Board, which seems determined to end off-road During my first year in office I had the honor of recreation at this historically important site for OHV assisting CORVA Board members Bob Ham, Ed Stovin enthusiasts. This is going to be tough battle but with and Bruce Whitcher, along with our Managing Director your support CORVA will do all we can do to protect Amy Granat; change SB 249 from a punitive bill that this recreation area. But this time we need OHV after- would have hurt the California OHMVR program, into market manufacturers and all OHV-related businesses a bill which made our OHMVR program a permanent to support our legal efforts. -

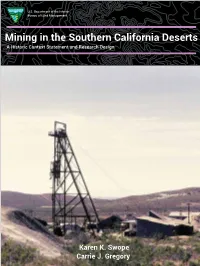

Mining in the Southern California Deserts a Historic Context Statement and Research Design Bob Wick, BLM

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Mining in the Southern California Deserts A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Bob Wick, BLM Karen K. Swope Carrie J. Gregory Mining in the Southern California Deserts: A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Karen K. Swope and Carrie J. Gregory Submitted to Sterling White Desert District Abandoned Mine Lands and Hazardous Materials Program Lead U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Prepared for James Barnes Associate State Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California State Office 2800 Cottage Way, Ste. W-1928 Sacramento, CA 95825 and Tiffany Arend Desert District Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Technical Report 17-42 Statistical Research, Inc. Redlands, California Mining in the Southern California Deserts: A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Karen K. Swope and Carrie J. Gregory Submitted to Sterling White Desert District Abandoned Mine Lands and Hazardous Materials Program Lead U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Prepared for James Barnes Associate State Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California State Office 2800 Cottage Way, Ste. W-1928 Sacramento, CA 95825 and Tiffany Arend Desert District Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Technical Report 17-42 Statistical Research, Inc.