Bangarra Dance Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE EDUCATION NOTES ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated December 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that these Education Notes contain names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Elma Kris, Rika Hamaguchi and Tyrel Dulvarie, photos by Daniel Boud & Jacob Nash, image created by Jacob Nash Back Cover: Elma Kris, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION Bangarra is rooted in two worlds, and through dance we connect to both, embodying ancient practices and igniting contemporary songlines. Our productions are our contemporary acts of ceremony, our way of protecting and preserving our unique songline. Knowledge Ground: 30 years of sixty five thousand is a curated collection of the arfefacts of these ceremonies – iconic set pieces, soundscapes, and costumes, which reveal the influences and themes that underpin our practice. -

Bangarra Dance Theatre: Rethinking Indigeneity in Australia

Bangarra Dance Theatre: Rethinking Indigeneity in Australia A thesis by: Charlotte Schuitenmaker 10212795 rMA Art Studies Supervisor: Dr. B. Titus Second reader: Prof. Dr. J.J.E. Kursell University of Amsterdam 21/01/2019 CONTENT INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….. 3 1 – BANGARRA’S EXPRESSIONS…...…………………………………………9 1.1 – Dance and Indigenous Australia………………………………………9 1.1.1 – Dance and music as modes of expression…………………...11 1.1.2 – Dance and music as systems of authority…………………...14 1.2 – Contemporary dancing………………………………………………..15 1.2.1 – Contemporary dance: An Overview......................................15 1.2.2 – Bangarra’s dance…………………………………………….20 1.3 – Presenting Indigeneity………………………………………………...22 1.3.1 – Bangarra’s performances…………………………………….22 1.3.2 – Bangarra’s promotion………………………………………. 31 2 – REASSEMBLING BANGARRA: THE INSTITUTION AS AND WITHIN A NETWORK……………………. 34 2.1 – Bangarra’s establishment……………………………………………...37 2.2 – A Page family business: choreographer, dancer and songman………. 39 2.3 – The theatre…………………………………………………………… 45 2.4 – Audiences and tickets………………………………………………....49 2.5 – Institutions and modernity...................................................................51 3 – MESSAGES: THE POLITICS OF IDENTITY AND STORIES…………54 3.1 – Indigeneity as identity…………………………………………………55 3.2 – Contemporary storytelling…………………………………………….60 3.2.1 – Stories: past-present-future…………………………….…....64 CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………….……67 REFERENCES……………………………………………………….……….……71 2 INTRODUCTION The Bangarra Dance Theatre Company is a Sydney-based institution that produces contemporary dance theatre shows inspired by Indigenous cultures in Australia. Carole Johnson, a dancer of African-American heritage, established the company in 1989, with Stephen George Page as Artistic Director since 1991. Page’s Aboriginal heritage stems from both the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali, a clan of the Yugambeh tribe in the south east of Queensland. Since 1992 the company has produced new shows almost annually and the team tours across the country. -

Dubboo Life of a Songman Program Credits

Dubboo: Life of A Songman Program Credits Directed by WAYNE BLAIR & NEL MINCHIN Produced by IVAN O’MAHONEY Cultural Producers BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE Edited by NICK MEYERS ASE Music by DAVID PAGE “DUBBOO – LIFE OF A SONGMAN” Co-presented by Carriageworks & Bangarra Dance Theatre Artistic Director STEPHEN PAGE Creative Ensemble ARCHIE ROACH DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN URSULA YOVICH BEN GRAETZ HUNTER PAGE-LOCHARD BRENDON BONEY BANGARRA DANCERS STEPHEN PAGE JENNIFER IRWIN JACOB NASH ALANA VALENTINE MATT COX Music Production & Arrangement STEVE FRANCIS String Arrangements IAIN GRANDAGE 1 String Quartet VERONIQUE SERRET STEPHANIE ZARKA CARL ST. JACQUES PAUL GHICA Stage Director PETER SUTHERLAND Director, Technical & Production JOHN COLVIN Rehearsal Director DANIEL ROBERTS Production Manager CAT STUDLEY Company Manager CLOUDIA ELDER Stage Manager LILLIAN HANNAH U Head Electrician CHRIS DONNELLY Head of Wardrobe MONICA SMITH Sound & AV Technician EMJAY MATTHEWS Production Trainee STEPH STORR Bangarra extends their thanks to the many people who helped bring together this celebration. A special thank you to the Page family for entrusting the company with this important work to honour their brother, son and uncle. Featured Bangarra productions Brolga (2001), Fish (1997), Spear (2015 feature film), Skin (2000), Ninni (1994), Bush, Praying Mantis Dreaming (1992), Ochres (1995) Key Credits STEPHEN PAGE FRANCES RINGS DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN DAVID PAGE 2 STEVE FRANCIS JOHN MATKOVIC PETER ENGLAND JENNIFER IRWIN JOSEPH MERCURIO EMILY AMISANO MARK HOWETT ARCHIE -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

A Study Guide by Katy Marriner

A FOOT IN EACH WORLD. A HEART IN NONE © ATOM 2016 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-936-8 http://theeducationshop.com.au Spear (2015), a feature film directed by Stephen Page, tells an Indigenous Australian story through movement, dance, sound, visual design and digital Australian Curriculum Learning media. A young Aboriginal man Djali journeys through his community Areas: Year 10 attempting to understand what it means to be a man. Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers English are advised that Spear contains voices and names of http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/english/ deceased people. curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level10 Curriculum links Humanities and Social Sciences: History http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ Spear is suitable for secondary students in Years humanities-and-social-sciences/history/curriculum/f- 10 – 12 in the learning areas of Dance, Drama, 10?layout=1#level10 English, History and Media. The Arts: Dance Spear can be used as a resource to address the http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/the-arts/ Australian Curriculum: Cross-curriculum priority – dance/curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level9-10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures. The film’s depiction of the experiences of Indigenous Australians, particularly of adult males, The Arts: Drama provides opportunities for students to engage in http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/the-arts/ discussions about Indigenous Australian identity drama/curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level9-10 and belonging and to examine the influences of tra- ditional Indigenous views and values, as well as the The Arts: Media Arts impact of the views and values of contemporary Australian society. -

Dark-Emu Studyguide.Pdf

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated September 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Bangarra ensemble, photo by Daniel Boud Back Cover: Yolanda Lowatta, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Inspired by Bruce Pascoe’s award-winning book of the same name, Dark Emu explores the vital life force 03 of flora and fauna in a series of dance stories. Directed Introduction by Stephen Page, Dark Emu is a dramatic and evocative dance response to the assault on land, people and spirit. We celebrate this sharing of knowledge, the heritage 04 of careful custodianship, and the beauty that Bruce Using this Study Guide Pascoe’s vision urges us to leave to the children. -

30Years Studyguide.Pdf

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated September 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains images, names, and writings of deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Rika Hamaguchi and Tyrel Dulvarie, photo by Daniel Boud Back Cover: Rika Hamaguchi, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS The purpose of this Study Guide is to provide information and contextual background about the works presented 03 in Bangarra Dance Theatre’s 30th anniversary season, Introduction/Contents Bangarra: 30 years of sixty five thousand. Reading the Guide, discussing the themes, and responding to the questions proposed, will assist teachers and students in thinking critically about the works, and form 04 Using this Study Guide personal responses. We encourage students and teachers to engage emotionally and imaginatively with the performance 05 Contemporary Indigenous Dance Theatre and to be curious about how these works were inspired and how they impact audiences. -

Reconciliation News October 2019

News ReconciliationStories about Australia’s journey to equality and unity Luke Pearson talks IndigenousX Bangarra Dance Theatre turns 30! Preserving the songs of Arrernte women TREATIES: THE MOMENTUM IS BUILDING 42 October 2019 Reconciliation News is a national magazine produced by Reconciliation Australia twice a year. Its aim is to inform and inspire readers with stories relevant to the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians. CONTACT US JOIN THE CONVERSATION reconciliation.org.au facebook.com/ReconciliationAus [email protected] twitter.com/RecAustralia 02 6273 9200 @reconciliationaus Reconciliation Australia acknowledges the Traditional Reconciliation Australia is an independent, not-for- Owners of Country throughout Australia and profit organisation promoting reconciliation by building recognises their continuing connection to lands, relationships, respect and trust between the wider waters and communities. We pay our respects to Australian community and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Islander peoples. Visit reconciliation.org.au Elders both past and present. to find out more. Cover: Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Tyrel Dulvarie. Image by Daniel Boud. Issue no. 42 / October 2019 3 CONTENTS FEATURES 8 Bangarra turns 30! To mark its 30-year anniversary, Bangarra Dance Theatre has just completed a triumphant four-month national tour. 10 Treaties: the momentum is building As the Uluru Statement from the Heart records, treaty-making is a key aspiration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 12 The Arrernte Women’s Project: Songs to Live By 10 Rachel Perkins pens a moving essay on her journey to record the sacred songs of Arrernte women in Central Australia. -

Australian Curriculum References

2 Dear Teacher, The information in this pack provides essential information and contextual background for the three dance works, Macq, Miyagan and Nyapanyapa, which make up the program, Our Land People Stories. We hope this resource will be useful in preparing your students to experience the work of Bangarra fully, and provide guidance for your focus on any curriculum material you wish to incorporate into the excursion. The material provided is not prescriptive in term of intent or meaning, and allows for individual responses to the works. The resource includes links to the Australian curriculum: Cross-curricula priority: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories & Cultures; General Capabilities: Critical and Creative Thinking, Intercultural Understanding and Literacy. Contents Bangarra Dance Theatre …………………………………………….. 3 Connecting to the source……………………………………………... 3 OUR land people stories……………………………………………… 5 Macq …………………………………………...……………. 5 Miyagan ……………………………………………………… 9 Nyapanyapa …………………………………………...…… 10 Key words / Glossaries ……………………………………………… 16 Bringing the stories to the stage …………………………………… 17 Acknowledgements..………………………………………………… 19 Curriculum links ……………………………………………………… 20 Australian Curriculum Stage 3 (Y5 & 6)………………….. 20 Australian Curriculum Stage 4 (Y7 & 8) …………………. 21 Australian Curriculum Stage 5 (Y9 & 10) ……………….. 21 2 3 Bangarra Dance Theatre … who is Bangarra? Bangarra is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for its powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music, and design. Bangarra was founded in 1989 by American dancer and choreographer, Carole Johnson. Since 1991 Bangarra has been led by Artistic Director and choreographer, Stephen Page. The company is based at Walsh Bay in Sydney and presents performance seasons in Australian capital cities, regional towns, and remote areas. -

Bangarra Dance Theatre

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated August 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains names of and quotes from deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Deborah Brown, photo by Greg Barrett Back Cover: Deborah Brown, photo by Greg Barrett 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Terrain is Bangarra Dance Theatre’s twentieth production and was the first full-length work for 03 the company by Choreographer and Associate Introduction Artistic Director, Frances Rings. 04 Using this Study Guide Landscape is at the core of our existence 05 and is a fundamental connection between Contemporary Indigenous Dance Theatre us and the natural world. The power of that connection is immeasurable. It cleanses, 09 it heals, it awakens and it renews. It gives Bangarra Dance Theatre us perspective. -

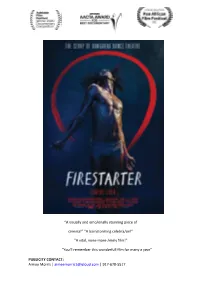

“A Visually and Emo/Onally Stunning Piece of Cinema!” “A

“A visually and emo/onally stunning piece of cinema!” “A barnstorming celebra/on!” “A vital, none-more-/mely film!” “You’ll remember this wonderfull film for many a year” PUBLICITY CONTACT: Aimee Morris | [email protected] | 917-670-5517 LOGLINE Firestarter marks Bangarra Dance Theatre’s 30th anniversary. Taking us through Bangarra’s birth and spectacular growth, the film recognises Bangarra’s founders and tells the story of how three young Aboriginal brothers — Stephen, David and Russell Page — turned the newly born dance group into a First Nations cultural powerhouse. But as Firestarter reveals, the company’s (inter)national success – the NY Times called Bangarra ‘a company like no other’ – came at a huge personal cost. As it enters its fourth decade Stephen must lead the company alone, finding a way to channel grief and sorrow into the strength to forge ahead, with a new generation of Indigenous dancers relying on his genius to tell their stories. Through the eyes of the brothers and company alumni, Firestarter explores the loss and reclaiming of culture, the burden of intergenerational trauma, and – crucially – the power of art as a messenger for social change and healing. SYNOPSIS “As the 20th century turns into the 21st, you can’t tell the story of Aboriginal Australia without featuring Bangarra – indeed they tell the story. And at the core of it there are these three beautiful boys. The holy trinity.” – Hetti Perkins, Art Curator, author. Hetti Perkins sums it up perfectly. Bangarra Dance Theatre, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary, is Australia’s most successful contemporary dance company. -

Annual Report 2020 | 1 Bennelong Rehearsal Photo, Featuring (L to R) Elma Kris, Beau Dean Riley Smith, Rika Hamaguchi and Nicola Sabatino (Jan 2020)

2020 Annual Report Bangarra Dance Theatre Annual Report 2020 | 1 Bennelong rehearsal photo, featuring (L to R) Elma Kris, Beau Dean Riley Smith, Rika Hamaguchi and Nicola Sabatino (Jan 2020) 2 | Connecting with Community CONTENTS Chair’s Report 4 Artistic Director’s Report 6 Executive Director’s Report 8 Company Profile 12 A Year in Review 14 Awards 16 Our Mission 18 Experiences 21 Connecting with Community 32 Youth and Outreach Programs 38 Russell Page Graduate Program 42 Returning to the Wharf 44 The Year Ahead 46 The Company 48 Partners 52 Patrons 54 Board of Directors 58 Governance 61 Image credits 63 CHAIR’S REPORT I was honoured to take on the role of Chair of guidance and leadership navigating our way Bangarra Dance Theatre in April 2020, after through this year. Our thanks also goes to acting as the Interim Chair for the previous Stephen Page, Frances Rings and all the five months. I have long admired the qualities Bangarra team for their agility, resilience, of kinship, respect, cultural integrity and energy and focus on connecting with our connection inherent in the company, and in audiences and caring for our Community. this challenging year I witnessed these values I acknowledge the support of the Federal provide the strong foundation for facing and NSW governments, and the many private adversity with resilience and strength. companies and individuals that support During the year we welcomed three new us. I would also acknowledge International Board members – in March we welcomed Towers, for providing such a welcoming back Lynn Ralph to assist Bangarra navigate temporary home whilst our studios at the COVID-19 impacts and new appointees Wharf underwent renovation.