A World of Science and Mystery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Records of 10 Bat Species in Guyana and Comments on Diversity of Bats in Iwokrama Forest

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks Acta Chiropterologica, l(2): 179-190,1999 PL ISSN 1508-1 109 O Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS First records of 10 bat species in Guyana and comments on diversity of bats in Iwokrama Forest BURTONK. LIM', MARKD. ENGSTROM~,ROBERT M. TIMM~,ROBERT P. ANDERSON~, and L. CYNTHIAWATSON~ 'Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen's Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada; E-mail: [email protected] 2Natural History Museum and Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-2454, USA 3Centrefor the Study of Biological Diversity, University of Guyana, Turkeyen Campus, East Coast Demerara, Guyana Ten species of bats (Centronycteris-maximiliani,Diclidurus albus, D. ingens, D. isabellus, Peropteryx leucoptera, Micronycteris brosseti, M. microtis, Tonatia carrikeri, Lasiurus atratus, and Myotis riparius) collected in the Iwokrarna International Rain Forest Programme site represent the first records of these taxa from Guyana. This report brings the known bat fauna of Guyana to 107 species and the fauna of Iwokrama Forest to 74 species. Measurements, reproductive data, and comments on taxonomy and distribution are provided. Key words: Chiroptera, Neotropics, Guyana, Iwokrama Forest, inventory, species diversity on the first of two field trips that constituted the mammal portion of the faunal survey for The mammalian fauna of Guyana is Iwokrama Forest coordinated through The poorly documented in comparison with Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadel- neighbouring countries in northern South phia. Records from previously unreported America. Most of its species and their distri- specimens at the Royal Ontario Museum are butions are inferred (e.g., Eisenberg, 1989) also presented to augment distributional data. -

Artibeus Jamaicensis) with Tacaribe Virus Ann C

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 8-1-2011 Experimental infection of Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis) with Tacaribe virus Ann C. Hawkinson Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Hawkinson, Ann C., "Experimental infection of Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis) with Tacaribe virus" (2011). Dissertations. Paper 150. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School Experimental Infection of Jamaican Fruit Bats (Artibeus jamaicensis) With Tacaribe Virus A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ann C. Hawkinson College of Natural Health Sciences School of Biological Sciences Biological Education August 2011 This Dissertation by: Ann C. Hawkinson Entitled: Experimental infection of Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis) with Tacaribe virus has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in College of Natural Health Sciences, in School of Biological Sciences, Program of Biological Education Accepted by the Doctoral Committee William A. Schountz, Ph.D., Chair Susan M. Keenan, Ph.D., Committee Member Rick A. Adams, Ph.D., Committee Member Steven Pulos, Ph.D., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense Accepted by the Graduate School Robbyn R. Wacker, Ph.D. Assistant Vice President for Research Dean of the Graduate School & International Admissions ABSTRACT Hawkinson, Ann C. -

Microchiroptera: Mystacinidae) from Australia, with a Revised Diagnosis of the Genus

New Miocene Icarops material (Microchiroptera: Mystacinidae) from Australia, with a revised diagnosis of the genus SUZANNE HAND, MICHAEL ARCHER & HENK GODTHELP HAND, S.l., ARCHER, M. & GODTHELP, H., 2001:12:20. New Miocene lcarops material (Microchiroptera: Mystacinidae) from Australia, with a revised diagnosis of the genus. Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists 25,139-146. ISSN 0810-8889 New fossil material referable to Icarops paradox Hand et al., 1998 is described from the early Miocene Judith's Horizontalis Site in the Riversleigh World Heritage Property of northwestern Queensland. Fused dentaries contain the partial lower dentition of I. paradox. The diagnosis of the genus Icarops is revised. The new material confirms the identity of Icarops species as mystacinids and enablesre-examination of interrelationships between extinct and extant members of this Gondwanan bat family. S.J: Hand, M. Archer* & H. Godthelp, School of Biological Science, University of New South Wales,New South Wales, 2052; * also Australian Museum, 6-8 College St, Sydney, New South Wales,2000. Received ]4 December 2000 Keywords: Mystacinidae, Icarops, Mystacina, bat, lower dentition, Miocene, Riversleigh THE FIRST pre-Pleistocene record for the QMF refers to specimens held in the fossil Mystacinidae and first record of this bat family collections of the QueenslandMuseum, Brisbane. from outside New Zealand were reported by Hand et al. ( 1998) from Miocene sedimentsin Australia. SYSTEMAllC PALAEONTOLOGY Three species of the new mystacinid genus Icarops were described: Icarops breviceps from OrderCIllROPTERAB1wnenbach, 1779 the middle Miocene Bullock Creek deposit of the SuborderMICROCIllROPTERA Dobson, 1875 Northern Territory; I. aenae from the early SuperfamilyNocmIoNoIDEA Van Va1en, Miocene Wayne's Wok deposit, D Site Plateau, 1979 Riversleigh, northwestern Queensland; and I. -

Classification of Mammals 61

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORCHAPTER SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Classification © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC 4 NOT FORof SALE MammalsOR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 2ND PAGES 9781284032093_CH04_0060.indd 60 8/28/13 12:08 PM CHAPTER 4: Classification of Mammals 61 © Jones Despite& Bartlett their Learning,remarkable success, LLC mammals are much less© Jones stress & onBartlett the taxonomic Learning, aspect LLCof mammalogy, but rather as diverse than are most invertebrate groups. This is probably an attempt to provide students with sufficient information NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FORattributable SALE OR to theirDISTRIBUTION far greater individual size, to the high on the various kinds of mammals to make the subsequent energy requirements of endothermy, and thus to the inabil- discussions of mammalian biology meaningful. -

Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest

diversity Article Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest Lucas Damásio 1,2 , Laís Amorim Ferreira 3, Vinícius Teixeira Pimenta 3, Greiciane Gaburro Paneto 4, Alexandre Rosa dos Santos 5, Albert David Ditchfield 3,6, Helena Godoy Bergallo 7 and Aureo Banhos 1,3,* 1 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Campus Darcy Ribeiro, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília 70910-900, DF, Brazil 3 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Animal), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil; [email protected] (L.A.F.); [email protected] (V.T.P.); [email protected] (A.D.D.) 4 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Farmácia e Nutrição, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 5 Centro de Ciências Agrárias e Engenharias, Departamento de Engenharia Rural, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil 7 Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcântara Gomes, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rua São Francisco Xavier 524, Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro 20550-900, RJ, Brazil; [email protected] Citation: Damásio, L.; Ferreira, L.A.; * Correspondence: [email protected] Pimenta, V.T.; Paneto, G.G.; dos Santos, A.R.; Ditchfield, A.D.; Abstract: Faunal mortality from roadkill has a negative impact on global biodiversity, and bats are Bergallo, H.G.; Banhos, A. -

2017 West Angelas Ghost Bat Monitoring

Roy Hill Vertebrate Fauna Desktop Review 2017 West Angelas Ghost Bat Monitoring Rio Tinto Iron Ore January 2018 Page 0 of 42 2017 West Angelas Ghost Bat Monitoring DOCUMENT STATUS Revision Approved for Issue to Author Review / Approved for Issue No. Name Date B. Dalton 1 Chris Knuckey Morgan O’Connell 05/01/18 J. Symmons 2 Chris Knuckey Brad Durrant J. Symmons 29/01/18 “IMPORTANT NOTE” Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this report, its attachments or appendices may be reproduced by any process without the written consent of Biologic Environmental Survey Pty Ltd (“Biologic”). All enquiries should be directed to Biologic. We have prepared this report for the sole purposes of Rio Tinto Iron Ore (“Client”) for the specific purpose only for which it is supplied. This report is strictly limited to the Purpose and the facts and matters stated in it and does not apply directly or indirectly and will not be used for any other application, purpose, use or matter. In preparing this report we have made certain assumptions. We have assumed that all information and documents provided to us by the Client or as a result of a specific request or enquiry were complete, accurate and up-to-date. Where we have obtained information from a government register or database, we have assumed that the information is accurate. Where an assumption has been made, we have not made any independent investigations with respect to the matters the subject of that assumption. -

Halloween Icon Bats

Grey-headed flying fox. Photo: Andrew Mercer Bats- A Halloween Icon J. Morton Galetto, CU Maurice River Bats are the only mammals that can fly. Flying squirrels would more properly be called gliders since they can’t perform a sustained flight, but rather simply float from one place to another using a cape of sorts to soar. Over the years bats have been misunderstood and their history is shrouded in false legends, from transformations into vampires to attacking people’s hair. Yes, I’m in the Halloween spirit and it’s time to get ghoulish. In Australia I was fascinated by fruit bats (pteropus), the world’s largest member of their species. Since the face is fox-like they are commonly referred to as flying foxes. They become active before dusk and look like raptors with their 3-foot wing span, while their bodies are about 16” long. Their lifespan is 15-23 years. As dusk approached my amazement at seeing hundreds of flying foxes wheeling in the air seemed ridiculous to the Aussies. But come on, to an outsider it was incredible! Flying fox do not rely on echolocation as our bats do, but rather use their large eyes to find food. I witnessed the urban bat camps in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney that could house hundreds of thousands of these creatures. Because of their large colonies they have a number of detractors. But large numbers in only a few congregations often make a species more vulnerable to extinction. Loss of habitat, slow reproduction, and high juvenile mortality are factors as well. -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

Food Choice in Frugivorous Bats

Food Choice in Frugivorous Bats Lauren Riegler Department of Biology, Trinity University ABSTRACT Frugivorous bats are important dispersers for many tropical plants and their conservation depends on furthering knowledge in their foraging behaviors and food preferences (Brosset et al. 1996). This study investigated a possible fruit preference of five frugivorous bat species (Carollia brevicauda, Artibeus lituratus, Artibeus jamaicensis, Artibeus toltecus and Platyrrhinus vittatus) found in Monteverde, Costa Rica among three wild fruit species (Solanum umbellatum, Solanum aphyodendron and Ficus pertusa) and two cultivated fruit species (Musa accuminata and Carica papaya). Fruits were presented to the bats in the Bat Jungle of Monteverde, where the foraging of bats can be closely observed. Artibeus toltecus showed a slight trend of preference for Solanum umbellatum over Solanum aphyodendron. However, due to small sample size and pseudoreplication there was no significant preference for any of the fruits by any of the bat species. RESUMEN Los murciélagos frugívoros son dispersores importantes de muchas plantas tropicales y su conservación depende del incremento de nuestro conocimiento de su comportamiento de forrajeo y preferencias dietéticas (Brosset et al. 1996). Este estudio investigó la posible predilección de cinco murciélagos frugívoros (Carollia brevicauda, Artibeus lituratus, Artibeus jamaicensis, Artibeus toltecus y Platyrrhinus vittatus) por tres especies silvestres de frutas Solanum umbellatum, Solanum aphyodendron y Ficus pertusa) y dos especies de frutas cultivadas (Musa accuminata y Carica papaya) en Monteverde, Costa Rica. Las frutas fueron presentadas a los murciélagos en la Jungla de Murciélagos de Monteverde, donde fue posible observar detenidamente el compartimiento de los murciélagos. Artibeus toltecus mostró una tendencia leve de preferencia por Solanum umbellatum. -

Andhra Pradesh

PROFILES OF SELECTED NATIONAL PARKS AND SANCTUARIES OF INDIA JULY 2002 EDITED BY SHEKHAR SINGH ARPAN SHARMA INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION NEW DELHI CONTENTS STATE NAME OF THE PA ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR CAMPBELL BAY NATIONAL PARK ISLANDS GALATHEA NATIONAL PARK MOUNT HARRIET NATIONAL PARK NORTH BUTTON ISLAND NATIONAL PARK MIDDLE BUTTON ISLAND NATIONAL PARK SOUTH BUTTON ISLAND NATIONAL PARK RANI JHANSI MARINE NATIONAL PARK WANDOOR MARINE NATIONAL PARK CUTHBERT BAY WILDLIFE SANCTUARY GALATHEA BAY WILDLIFE SANCTUARY INGLIS OR EAST ISLAND SANCTUARY INTERVIEW ISLAND SANCTUARY LOHABARRACK OR SALTWATER CROCODILE SANCTUARY ANDHRA PRADESH ETURUNAGARAM SANCTUARY KAWAL WILDLIFE SANCTUARY KINNERSANI SANCTUARY NAGARJUNASAGAR-SRISAILAM TIGER RESERVE PAKHAL SANCTUARY PAPIKONDA SANCTUARY PRANHITA WILDLIFE SANCTUARY ASSAM MANAS NATIONAL PARK GUJARAT BANSDA NATIONAL PARK PURNA WILDLIFE SANCTUARY HARYANA NAHAR SANCTUARY KALESAR SANCTUARY CHHICHHILA LAKE SANCTUARY ABUBSHEHAR SANCTUARY BIR BARA VAN JIND SANCTUARY BIR SHIKARGAH SANCTUARY HIMACHAL PRADESH PONG LAKE SANCTUARY RUPI BHABA SANCTUARY SANGLA SANCTUARY KERALA SILENT VALLEY NATIONAL PARK ARALAM SANCTUARY CHIMMONY SANCTUARY PARAMBIKULAM SANCTUARY PEECHI VAZHANI SANCTUARY THATTEKAD BIRD SANCTUARY WAYANAD WILDLIFE SANCTUARY MEGHALAYA BALPAKARAM NATIONAL PARK SIJU WILDLIFE SANCTUARY NOKREK NATIONAL PARK NONGKHYLLEM WILDLIFE SANCTUARY MIZORAM MURLEN NATIONAL PARK PHAWNGPUI (BLUE MOUNTAIN) NATIONAL 2 PARK DAMPA WILDLIFE SANCTUARY KHAWNGLUNG WILDLIFE SANCTUARY LENGTENG WILDLIFE SANCTUARY NGENGPUI WILDLIFE -

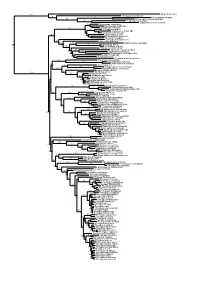

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

A Sampling of the Bats of Nicaragua

By Carol Chambers White-throated round-eared bats (Lophostoma si/vico/um) roost in termite nests in trees in Nicaragua's Paso del lstmo, as they do elsewhere in Central America. he few remaining patches of old-growth quences for forests and wildlife. My colleagues and I came to tropical dry forest of Nicaragua's Paso del Nicaragua to study how forest fragmentation impacts bat com T Istmo offer enchanting landscapes. Shaded munities. That research continues, but we've already made some and cool, they are alive with movement and sound as monkeys, exciting discoveries. birds and other creatures cavort among the trees. At night, fire I had visited this area previously with Suzanne Hagell, a for flies flicker like stars, creating the illusion of a night sky beneath mer graduate student at Northern Arizona University. Using ge the forest canopy. Tree trunks can be massive columns, as wide netic analysis, she discovered that black-handed spider monkeys as a picnic table, or tall sculptures buttressed with fins at the (Ateles geojfroyi) were significantly inbred, largely because of base. The hillsides are webbed with narrow paths created over their limited ability to move among the few large, disconnected many years by people, livestock or leaf-cutter ants. forest patches remaining on this landscape. Bats, however, are In contrast, traversing the young forests is often slow, hot more mobile than monkeys so their genetic diversity may be and difficult work. The small trees, shrubs and vines struggling less affected by forest fragmentation. to refill cleared terrain act as barricades to movement.