A Dissertation on “TWO YEARS STUDY of WORK PLACE DEATHS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

Quotation Without DD Will Be Rejected

SOUTHERN RAILWAY No. M/C 37/Pub/Quotation/MAS Divn/18 of 05.04.2018 1. Name of work : Separate quotations for the Bulk rights advertisements for a period up to 30.09.2018 at Railway stations over Chennai Division. 2. Location : List of Stations may be seen in the website. 3. Approx. cost of the work : May be seen in the website. 4. Cost of tender form : May be seen in the website. 5. Address of the office from where the quotation form can be purchased : The Divisional Railway Manager / Commercial, NGO Annexe 2 nd Floor, Park Town, Southern Railway, Chennai –600 003. 6. Earnest money deposit : -Nil- : 7. Date and time for submission of quotation. : on 13.04.2018 between 10.00 hrs to 11.00hrs. 9. Opening of quotation form : 11.30 hrs on 13.04.2018 10. Enclosure : Each quotation should be accompanied by demand draft drawn in favour of FA & CAO/S.Rly/Chennai towards covering the value quoted in the quotation. 11. Website address : www.sr.indianrailways.gov.in Note: Quotation without DD will be rejected. If the date of receipt and opening of quotations happens to be declared as Holiday, the same will be on the next working day. /Divisional Railway Manager/ Commercial, Southern Railway. Chennai-600 003. SOUTHERN RAILWAY No. M/C 37/Pub/Quotation/MAS Divn/18 of 05.04.2018 The Divisional Railway Manager / Commercial, Southern Railway , Chennai –600 003 invites separate quotations for the Bulk rights advertisements for a period up to 30.09.2018 at Railway stations over Chennai Division as detailed below: STN RP For 6 Months S.No Code Station Name -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Properties

ANNEXURE – 15 [See Proviso to Rule 8(6)] SALE NOTICE FOR SALE OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTIES E-Auction Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Assets under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 read with provisio to Rule 8(6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002 Notice is hereby given to the public in general and in particular to the Borrower(s) and Guarantor(s) that the below described immovable properties mortgaged to the Secured Creditor, the constructive possession of which has been taken by the Authorised Officer of State Bank of India, being the Secured Creditor, will be sold on “Äs is where is”, “As is what is “, and “Whatever there is” basis on 10.02.2021 for recovery of ₹2,69,06,476.98 (Rupees Two Crores Sixty Nine Lakhs Six Thousands Four Hundred and Seventy Six Paise Ninety Eight Only) as on 31.12.2020 with future interest and costs due to the State Bank of India, SARB, Chennai from the Borrower(s) and the Guarantor(s) as mentioned below. The Reserve Price and the Earnest Money Deposit (EMD) as mentioned below, the latter amount to be deposited with the Bank, on or before 08.02.2021 Name of the Borrowers and Guarantors Perfect Vending (India) Pvt Ltd, Shri. Sanjeev Mohan Perfect Vending (India) Pvt Ltd., 4B-1 KSR Main Road, S/o Shri. G Mohan Das, 1/46, Pandurangapuram, Padi, KSR Nagar, Near Telephone Flat No.E, Spring Wood Apts., Chennai – 600 050 Exchange, Ambattur, No.6, Ranjith Road, Kotturpuram, Chennai – 600 053 Chennai – 600 085 Shri. -

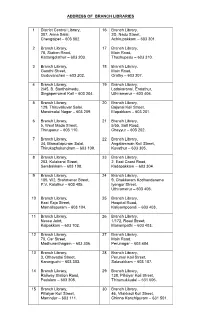

Branch Libraries List

ADDRESS OF BRANCH LIBRARIES 1 District Central Library, 16 Branch Library, 307, Anna Salai, 2D, Nadu Street, Chengalpet – 603 002. Achirupakkam – 603 301. 2 Branch Library, 17 Branch Library, 78, Station Road, Main Road, Kattangolathur – 603 203. Thozhupedu – 603 310. 3 Branch Library, 18 Branch Library, Gandhi Street, Main Road, Guduvancheri – 603 202. Orathy – 603 307. 4 Branch Library, 19 Branch Library, 2/45, B. Santhaimedu, Ladakaranai, Endathur, Singaperrumal Koil – 603 204. Uthiramerur – 603 406. 5 Branch Library, 20 Branch Library, 129, Thiruvalluvar Salai, Bajanai Koil Street, Maraimalai Nagar – 603 209. Elapakkam – 603 201. 6 Branch Library, 21 Branch Library, 5, West Mada Street, 5/55, Salt Road, Thiruporur – 603 110. Cheyyur – 603 202. 7 Branch Library, 22 Branch Library, 34, Mamallapuram Salai, Angalamman Koil Street, Thirukazhukundram – 603 109. Kuvathur – 603 305. 8 Branch Library, 23 Branch Library, 203, Kulakarai Street, 2, East Coast Road, Sembakkam – 603 108. Kadapakkam – 603 304. 9 Branch Library, 24 Branch Library, 105, W2, Brahmanar Street, 9, Chakkaram Kodhandarama P.V. Kalathur – 603 405. Iyengar Street, Uthiramerur – 603 406. 10 Branch Library, 25 Branch Library, East Raja Street, Hospital Road, Mamallapuram – 603 104. Kaliyampoondi – 603 403. 11 Branch Library, 26 Branch Library, Nesco Joint, 1/172, Road Street, Kalpakkam – 603 102. Manampathi – 603 403. 12 Branch Library, 27 Branch Library, 70, Car Street, Main Road, Madhuranthagam – 603 306. Perunagar – 603 404. 13 Branch Library, 28 Branch Library, 3, Othavadai Street, Perumal Koil Street, Karunguzhi – 603 303. Salavakkam – 603 107. 14 Branch Library, 29 Branch Library, Railway Station Road, 138, Pillaiyar Koil Street, Padalam – 603 308. -

T.Y.B.A. Paper Iv Geography of Settlement © University of Mumbai

31 T.Y.B.A. PAPER IV GEOGRAPHY OF SETTLEMENT © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Dr. Sanjay Deshmukh Vice Chancellor, University of Mumbai Dr.AmbujaSalgaonkar Dr.DhaneswarHarichandan Incharge Director, Incharge Study Material Section, IDOL, University of Mumbai IDOL, University of Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Anil R. Bankar Asst. Prof. CumAsst. Director, IDOL, University of Mumbai. Course Co-ordinator : Ajit G.Patil IDOL, Universityof Mumbai. Editor : Dr. Maushmi Datta Associated Prof, Dept. of Geography, N.K. College, Malad, Mumbai Course Writer : Dr. Hemant M. Pednekar Principal, Arts, Science & Commerce College, Onde, Vikramgad : Dr. R.B. Patil H.O.D. of Geography PondaghatArts & Commerce College. Kankavli : Dr. ShivramA. Thakur H.O.D. of Geography, S.P.K. Mahavidyalaya, Sawantiwadi : Dr. Sumedha Duri Asst. Prof. Dept. of Geography Dr. J.B. Naik, Arts & Commerce College & RPD Junior College, Sawantwadi May, 2017 T.Y.B.A. PAPER - IV,GEOGRAPHYOFSETTLEMENT Published by : Incharge Director Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTP Composed : Ashwini Arts Gurukripa Chawl, M.C. Chagla Marg, Bamanwada, Vile Parle (E), Mumbai - 400 099. Printed by : CONTENTS Unit No. Title Page No. 1 Geography of Rural Settlement 1 2. Factors of Affecting Rural Settlements 20 3. Hierarchy of Rural Settlements 41 4. Changing pattern of Rural Land use 57 5. Integrated Rural Development Programme and Self DevelopmentProgramme 73 6. Geography of Urban Settlement 83 7. Factors Affecting Urbanisation 103 8. Types of -

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

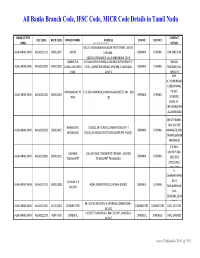

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Global Retinoblastoma Presentation and Analysis by National Income Level

Research JAMA Oncology | Original Investigation Global Retinoblastoma Presentation and Analysis by National Income Level Global Retinoblastoma Study Group Supplemental content IMPORTANCE Early diagnosis of retinoblastoma, the most common intraocular cancer, can save both a child’s life and vision. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that many children across the world are diagnosed late. To our knowledge, the clinical presentation of retinoblastoma has never been assessed on a global scale. OBJECTIVES To report the retinoblastoma stage at diagnosis in patients across the world during a single year, to investigate associations between clinical variables and national income level, and to investigate risk factors for advanced disease at diagnosis. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A total of 278 retinoblastoma treatment centers were recruited from June 2017 through December 2018 to participate in a cross-sectional analysis of treatment-naive patients with retinoblastoma who were diagnosed in 2017. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Age at presentation, proportion of familial history of retinoblastoma, and tumor stage and metastasis. RESULTS The cohort included 4351 new patients from 153 countries; the median age at diagnosis was 30.5 (interquartile range, 18.3-45.9) months, and 1976 patients (45.4%) were female. Most patients (n = 3685 [84.7%]) were from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Globally, the most common indication for referral was leukocoria (n = 2638 [62.8%]), followed by strabismus (n = 429 [10.2%]) and proptosis (n = 309 [7.4%]). Patients from high-income countries (HICs) were diagnosed at a median age of 14.1 months, with 656 of 666 (98.5%) patients having intraocular retinoblastoma and 2 (0.3%) having metastasis. -

Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78)

FAMINE, DISEASE, MEDICINE AND THE STATE IN MADRAS PRESIDENCY (1876-78). LEELA SAMI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U5922B8 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592238 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION OF NUMBER OF WORDS FOR MPHIL AND PHD THESES This form should be signed by the candidate’s Supervisor and returned to the University with the theses. Name of Candidate: Leela Sami ThesisTitle: Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78) College: Unversity College London I confirm that the following thesis does not exceed*: 100,000 words (PhD thesis) Approximate Word Length: 100,000 words Signed....... ... Date ° Candidate Signed .......... .Date. Supervisor The maximum length of a thesis shall be for an MPhil degree 60,000 and for a PhD degree 100,000 words inclusive of footnotes, tables and figures, but exclusive of bibliography and appendices. Please note that supporting data may be placed in an appendix but this data must not be essential to the argument of the thesis. -

Project Number: 39114 July 2007

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 39114 July 2007 India:Tsunami Emergency Assistance (Sector) Project Prepared by [Author(s)] [Firm] [City, Country] Prepared by Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Prepared for [Executing Agency] [Implementing Agency] The summary initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s be preliminary in nature. members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Table of Contents Initial Environmental Evaluation Report Page 1 Initial Environmental Evaluation Report Table of Contents • List of Abbreviation ............................................................................................... 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Background................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Project Influence Area / Corridor of Impact ............................................... 1-1 1.3 Available Right of Way ............................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Statutory Clearances ................................................................................