INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced from the Microfilm Master. UMI Films the Text Directly from the Origina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jonathan Berger, an Introduction to Nameless Love

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected], 646-492- 4076 Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love In collaboration with Mady Schutzman, Emily Anderson, Tina Beebe, Julian Bittiner, Matthew Brannon, Barbara Fahs Charles, Brother Arnold Hadd, Erica Heilman, Esther Kaplan, Margaret Morton, Richard Ogust, Maria A. Prado, Robert Staples, Michael Stipe, Mark Utter, Michael Wiener, and Sara Workneh February 23 – April 5, 2020 Opening Sunday, February 23, noon–7pm From February 23 – April 5, 2020, PARTICIPANT INC is pleased to present Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love, co-commissioned and co-organized with the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University. Taking the form of a large-scale sculptural installation that includes over 533,000 tin, nickel, and charcoal parts, Berger’s exhibition chronicles a series of remarkable relationships, creating a platform for complex stories about love to be told. The exhibition draws from Berger’s expansive practice, which comprises a spectrum of activity — brought together here for the first time — including experimental approaches to non-fiction, sculpture and installation, oral history and biography-based narratives, and exhibition-making practices. Inspired by a close friendship with fellow artist Ellen Cantor (1961-2013), An Introduction to Nameless Love charts a series of six extraordinary relationships, each built on a connection that lies outside the bounds of conventional romance. The exhibition is an examination of the profound intensity and depth of meaning most often associated with “true love,” but found instead through bonds based in work, friendship, religion, service, mentorship, community, and family — as well as between people and themselves, places, objects, and animals. -

Ass Spielkarten

Werbemittelkatalog www.werbespielkarten.com Spielkarten können das ASS im Ärmel sein ... Spielkarten als Werbemittel bleiben in Erinnerung – als kommunikatives Spielzeug werden sie entspannt in der Freizeit genutzt und eignen sich daher hervorragend als Werbe- und Informationsträger. Die Mischung macht‘s – ein beliebtes Spiel, qualitativ hochwertige Karten und Ihre Botschaft – eine vielversprechende Kombination! Inhalt Inhalt ........................................................................ 2 Unsere grüne Mission ............................... 2 Wo wird welches Blatt gespielt? ..... 3 Rückseiten ........................................................... 3 Brandneu bei ASS Altenburger ........ 4 Standardformate ........................................... 5 Kinderspiele ........................................................ 6 Verpackungen .................................................. 7 Quiz & Memo ................................................... 8 Puzzles & Würfelbecher ....................... 10 Komplettspiele .............................................. 11 Ideen ...................................................................... 12 Referenzen ....................................................... 14 Unsere grüne Mission Weil wir Kunden und Umwelt gleichermaßen verpflichtet sind ASS Altenburger will mehr erreichen, als nur seine geschäftlichen Ziele. Als Teil eines globalen Unternehmens sind wir davon überzeugt, eine gesellschaftliche Verantwortung für Erde, Umwelt und Menschen zu haben. Wir entscheiden uns bewusst -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer

03/05/2017 Arthur Schopenhauer (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer First published Mon May 12, 2003; substantive revision Sat Nov 19, 2011 Among 19th century philosophers, Arthur Schopenhauer was among the first to contend that at its core, the universe is not a rational place. Inspired by Plato and Kant, both of whom regarded the world as being more amenable to reason, Schopenhauer developed their philosophies into an instinctrecognizing and ultimately ascetic outlook, emphasizing that in the face of a world filled with endless strife, we ought to minimize our natural desires for the sake of achieving a more tranquil frame of mind and a disposition towards universal beneficence. Often considered to be a thoroughgoing pessimist, Schopenhauer in fact advocated ways — via artistic, moral and ascetic forms of awareness — to overcome a frustrationfilled and fundamentally painful human condition. Since his death in 1860, his philosophy has had a special attraction for those who wonder about life's meaning, along with those engaged in music, literature, and the visual arts. 1. Life: 1788–1860 2. The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason 3. Schopenhauer's Critique of Kant 4. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.1 Aesthetic Perception as a Mode of Transcendence 5.2 Moral Awareness as a Mode of Transcendence 5.3 Asceticism and the Denial of the WilltoLive 6. Schopenhauer's Later Works 7. Critical Reflections 8. Schopenhauer's Influence Bibliography Academic Tools Other Internet Resources Related Entries 1. Life: 1788–1860 Exactly a month younger than the English Romantic poet, Lord Byron (1788–1824), who was born on January 22, 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer came into the world on February 22, 1788 in Danzig [Gdansk, Poland] — a city that had a long history in international trade as a member of the Hanseatic League. -

The Two Souls of Schopenhauerism: Analysis of New Historiographical Categories

UFSM Voluntas: Revista Internacional de Filosofia DOI: 10.5902/2179378661962 Santa Maria, v.11, n. 3, p. 207-223 ISSN 2179-3786 Fluxo contínuo Submissão: 25/10/2020 Aprovação: 06/01/2021 Publicação: 15/01/2021 The two souls of Schopenhauerism: analysis of new historiographical categories Le due anime dello schopenhauerismo: analisi delle nuove categorie storiografiche Giulia Miglietta* Abstract: The Wirkungsgeschichte of Schopenhauerism is a complex mixture of events, encounters, influences and transformations. In order to orient oneself concerning such an articulated phenomenon, it is necessary to have valid hermeneutical tools at hand. In this contribution, I propose a reading of the Wirkungsgeschichte of Schopenhauerism through new and effective historiographical categories that resulted from the research conducted by the Interdepartmental Research Centre on Arthur Schopenhauer and his School at the University of Salento. On the one hand, I will refer to Domenico Fazio’s studies on the Schopenhauer-Schule and, on the other, to Fabio Ciracì’s research on the reception of Schopenhauer’s philosophy in Italy. This approach will reveal how the formulation of the so- called “two souls” of Schopenhauerism, the romantic and the illuministic, allows us to unravel the multifaceted panorama of the Wirkungsgeschichte of Schopenhauerian philosophy, in line with the subdivision within the Schopenhauer-Schule of metaphysical and heretical thinkers. Keyword: Schopenhauer; Wirkungsgeschichte; Illuministic soul; Romantic soul; Historiographical categories. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

For Immediate Release: October 6, 2017 Contact: Emma Watt/Mark Lunsford 617.496.8004 [email protected]

For Immediate Release: October 6, 2017 Contact: Emma Watt/Mark Lunsford 617.496.8004 [email protected] OBERON ANNOUNCES OCTOBER – NOVEMBER 2017 PROGRAMMING Cambridge, MA–OBERON, the American Repertory Theater’s (A.R.T.) second stage and club theater venue on the fringe of Harvard Square, announces events to be presented at OBERON during October and November — including A.R.T. Institute, OBERON Presents, Visiting Artists, and Usual Suspects. __________ MACBETH A.R.T. Institute Thursday, October 5 and Friday, October 6 at 7PM Tickets $20 After murdering their king, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth spiral ever deeper into the desperation and madness of guilt. Featuring the A.R.T. Institute for Advanced Theater Training Class of 2018, this new staging by Obie Award-winning director Melia Bensussen (Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief, A.R.T. Institute; A Doll’s House, Huntington Theatre Company) brings Macbeth into conversation with Edgar Allan Poe’s 19th century—when Gothic horror stories haunted the boundaries between the outside world and the individual unconscious. __________ YO SOY LOLA Sunday, October 8 at 8:30PM Tickets $25 - $50 Yo Soy LOLA is a thought-provoking multimedia experience showcasing Latinas in the arts and raising awareness of the multi-dimensional Latina experience. Net proceeds fund scholarships and artistic ideas that directly impact the next generation of Latinx youth and their communities. After the show, a Latin dance party continues into the night. __________ THE STORY COLLIDER Usual Suspect Wednesday, October 11 at 8PM Tickets $10 - $12 From finding awe in Hubble images to visiting the doctor, science is everywhere in our lives. -

Download Issue

Direttore editoriale: Roberto Finelli Vicedirettore: Francesco Toto Comitato scientifico: Riccardo Bellofiore (Univ. Bergamo), Jose Manuel Bermudo (Univ. Barcelona), Jacques Bidet (Univ. Paris X), Laurent Bove (Univ. Amiens), Giovanni Bonacina (Univ. Urbino), Giorgio Cesarale (Univ. Venezia), Francesco Fistetti (Univ. Bari), Lars Lambrecht (Univ. Hamburg), Christian Lazzeri (Univ. Paris X) Mario Manfredi (Univ. Bari), Pierre-François Moreau (ENS Lyon), Stefano Petrucciani (Univ. Roma-La Sapienza), Pier Paolo Poggio (Fondazione Micheletti-Brescia), Emmanuel Renault (ENS Lyon), Massimiliano Tomba (Univ. Padova), Sebastian Torres (Univ. Cordoba). Redazione: Miriam Aiello, Sergio Alloggio, Luke Edward Burke, Luca Cianca, Marta Libertà De Bastiani, Carla Fabiani, Pierluigi Marinucci, Jamila Mascat, Emanuele Martinelli, Luca Micaloni, Oscar Oddi, Giacomo Rughetti, Michela Russo, Laura Turano. Anno 1, n. 2, aprile 2017, Roma a cura di Miriam Aiello, Luca Micaloni, Giacomo Rughetti. Progetto grafico a cura di Laura Turano Immagine di copertina: Josef Albers - Tenayuca (1943) Rivista semestrale, con peer review ISSN: 2531-8934 www. consecutio.org Declinazioni del Nulla Non essere e negazione tra ontologia e politica a cura di Miriam Aiello, Luca Micaloni, Giacomo Rughetti Editoriale p. 5 Miriam Aiello, Una polifonia ‘negativa’ Monografica p. 11 Franca D'Agostini, Il nulla e la nascita filosofica dell'Europa p. 33 Roberto Morani, Figure e significati del nulla nel pensiero di Heidegger p. 49 Angelo Cicatello, Il negativo in questione. Una lettura di Adorno p. 65 Massimiliano Lenzi, In nihilum decidere. “Negatività” della creatura e nichilismo del peccato in Tommaso d’Aquino p. 89 Claude Romano, Osservazioni sulla «tavola del nulla» di Kant p. 99 Fabio Ciracì, Metafisiche del nulla. Schopenhauer, i suoi discepoli e l’incosistenza del mondo p. -

List of Compositions and Arrangements

Eduard de Boer: List of compositions and arrangements 1 2 List of Compositions and Arrangements I. Compositions page: — Compositions for the stage 5 Operas 5 Ballets 6 Other music for the theatre 7 — Compositions for or with symphony or chamber orchestra 8 for symphony or chamber orchestra 8 for solo instrument(s) and symphony or chamber orchestra 3 for solo voice and symphony orchestra : see: Compositions for solo voice(s) and accompaniment → for solo voice and symphony orchestra 45 for chorus and symphony or chamber orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and symphony or chamber orchestra 52 — Compositions for or with string orchestra 11 for string orchestra 11 for solo instrument(s) and string orchestra 13 for chorus and string orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and string orchestra 55 — Compositions for or with wind orchestra, fanfare orchestra or brass band 15 for wind orchestra 15 for solo instrument(s) and wind orchestra 19 for solo voices and wind orchestra : see: Compositions for solo voice(s) and accompaniment → for solo voices and wind orchestra 19 for chorus and wind orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and wind orchestra : 19 for fanfare orchestra 22 for solo instrument and fanfare orchestra 24 for chorus and fanfare orchestra : see: Choral music (with or without solo voice(s)) → for chorus and fanfare orchestra 56 for brass band 25 for solo instrument and brass band 25 — Compositions for or with accordion orchestra -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-2-2009 The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19" (2009). The Carroll News. 788. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/788 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Russert Fellowship Tribe preview NBC creates fellowship in How will Sizemore and honor of JCU grad, p. 3 the team stack up? p. 15 THE ARROLL EWS Thursday,C April 2, 2009 Serving John Carroll University SinceN 1925 Vol. 85, No. 19 ‘Help Me Succeed’ library causes campus controversy Max Flessner Campus Editor Members of the African The African American Alliance had to move quickly to abridge an original All-Stu e-mail en- American Alliance Student Union try they had sent out requesting people to donate, among other things, copies of old finals and mid- Senate votes for terms, to a library that the AAA is establishing as a resource for African American students on The ‘Help Me administration policy campus. The library, formally named the “Help Me Suc- Succeed’ library ceed” library, will be a collection of class materials to close main doors and notes. The original e-mail that was sent in the March to cafeteria 24 All-Stu, asked -

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

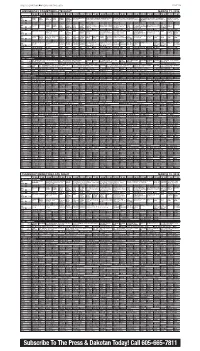

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Spielanleitung Holzspielesammlung (D).Qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 2

Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 1 D Spielanleitung Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 2 © Philos GmbH & Co. KG Friedrich-List-Str. 65 33100 Paderborn Germany www.philosspiele.de Holzspielesammlung (D).qxd 15.09.2009 10:44 Uhr Seite 3 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Spielpläne Brettspiele 1 Spielplan Immer mit der Ruhe – Mühle 1 Spielplan Barricade – Halma Schach . 18 1 Spielplan Backgammon – Schach / Dame Häuptling und Krieger . 20 Double-Schach . 20 K.-o.-Schach . 20 Spielmaterial Schlagschach . 20 50 Spielkegel (Holz): 15 blaue, 15 rote, Positionsschach . 20 15 grüne, 5 gelbe Dame . 20 41 Mikadostäbchen (Holz) Polnische Dame . 21 32 Schachfiguren (Holz) Französische Dame . 21 30 Spielsteine (Holz) Eckdame . 21 28 Dominosteine (Holz) Schlagdame . 22 20 Holzstäbchen Blockade . 22 11 Barricade-Sperrsteine (Holz) Contract-Checkers . 22 4 Würfel: 2 rote, 2 weiße Wolf und Schafe . 22 1 Dopplerwürfel Rösselsprung . 22 1 Würfelbecher Mühle . 23 2 Spielkarten-Sets (französisches Blatt) Die Lasker’sche Mühle . 24 Die Springermühle . 24 Würfelmühle . 24 Eckmühle . 25 Treibjagd . 25 Hüpfmühle . 25 Kreuzmühle . 25 Würfel-Brettspiele Halma . 26 Halma Solo . 26 Immer mit der Ruhe . 5 Das Partnerspiel . 5 ✦✦✦ Parken . 6 Crazy India . 6 Knobelspiele (Würfel) Frank und Furter . 6 Orbite . 6 Schaukel . 27 Ausreißer . 7 Nackter Spatz . 27 Barricade . 7 Die böse 3 . 27 Backgammon . 8 Sechzehn-tot . 27 Tric-Trac . 14 Stumme Jule . 28 Puff . 16 6er-Spiel . 28 Catch Me . 16 Zeppelin . 28 Chouette . 17 Hohe Hausnummer . 29 Jacquet . 17 101, aber keine Eins . 29 Doppelsteine . 17 Die lustige 7 . 29 Himmel und Hölle . 29 ✦✦✦ Elf hoch .