Ivar the Viking Ivar the Viking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor E

1 The Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor Erussard Stories that are passed down through oral and written traditions are created by societies to give meaning to, and reinforce the beliefs, rules and habits of a particular culture. For Germanic culture, The Saga of the Volsungs reflected the societal traditions of the people, as well as their attention to mythology. In the Saga, Sigurd of the Volsung 2 bloodline becomes a respected and heroic figure through the trials and adventures of his life. While many of his encounters are fantastic, they are also deeply rooted in the values and belief structures of the Germanic people. Tacitus, a Roman, gives his account of the actions and traditions of early Germanic peoples in Germania. His narration remarks upon the importance of the blood line, the roles of women and also the ways in which Germans viewed death. In Snorri Sturluson’s The Prose Edda, a compilation of Norse mythology, Snorri Sturluson touches on these subjects and includes the perception of fate, as well as the role of shape changing. Each of these themes presented in Germania and The Prose Edda aid in the formation of the legendary saga, The Saga of the Volsungs. Lineage is a meaningful part of the Germanic culture. It provides a sense of identity, as it is believed that qualities and characteristics are passed down through generations. In the Volsung bloodline, each member is capable of, and expected to achieve greatness. As Sigmund, Sigurd’s father, lay wounded on the battlefield, his wife asked if she should attend to his injuries so that he may avenge her father. -

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

The Prose Edda

THE PROSE EDDA SNORRI STURLUSON (1179–1241) was born in western Iceland, the son of an upstart Icelandic chieftain. In the early thirteenth century, Snorri rose to become Iceland’s richest and, for a time, its most powerful leader. Twice he was elected law-speaker at the Althing, Iceland’s national assembly, and twice he went abroad to visit Norwegian royalty. An ambitious and sometimes ruthless leader, Snorri was also a man of learning, with deep interests in the myth, poetry and history of the Viking Age. He has long been assumed to be the author of some of medieval Iceland’s greatest works, including the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, the latter a saga history of the kings of Norway. JESSE BYOCK is Professor of Old Norse and Medieval Scandinavian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Professor at UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. A specialist in North Atlantic and Viking Studies, he directs the Mosfell Archaeological Project in Iceland. Prof. Byock received his Ph.D. from Harvard University after studying in Iceland, Sweden and France. His books and translations include Viking Age Iceland, Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, Feud in the Icelandic Saga, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki and The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. SNORRI STURLUSON The Prose Edda Norse Mythology Translated with an Introduction and Notes by JESSE L. BYOCK PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN CLASSICS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., -

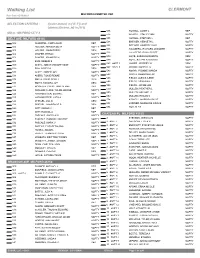

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021 SELECTION CRITERIA : ({voter.status} in ['A','I']) and {district.District_id} in [112] 535 HOWELL, JANET L REP MD-A - MILFORD CITY A 535 HOWELL, STACY LYNN NOPTY BELT AVE MILFORD 45150 535 HOWELL, STEPHEN L REP 538 BREWER, KENNETH L NOPTY 502 KLOEPPEL, CODY ALAN REP 538 BREWER, KIMBERLY KAY NOPTY 505 HOLSER, AMANDA BETH NOPTY 538 HALLBERG, RICHARD LEANDER NOPTY 505 HOLSER, JOHN PERRY DEM 538 HALLBERG, RYAN SCOTT NOPTY 506 SHAFER, ETHAN NOPTY 539 HOYE, SARAH ELIZABETH DEM 506 SHAFER, JENNIFER M NOPTY 539 HOYE, STEPHEN MICHAEL NOPTY 508 BUIS, DEBBIE S NOPTY 542 #APT 1 LANIER, JEFFREY W DEM 509 WHITE, JONATHAN MATTHEW NOPTY 542 #APT 3 MASON, ROBERT G NOPTY 510 ROA, JOYCE A DEM 543 AMAYA, YVONNE WANDA NOPTY 513 WHITE, AMBER JOY NOPTY 543 NORTH, DEBORAH FAY NOPTY 514 AKERS, TONIE RENAE NOPTY 546 FIELDS, ALEXIS ILENE NOPTY 518 SMITH, DAVID SCOTT DEM 546 FIELDS, DEBORAH J NOPTY 518 SMITH, TAMARA JOY DEM 546 FIELDS, JACOB LEE NOPTY 521 MCBEATH, COURTTANY ALENE REP 550 MULLEN, HEATHER L NOPTY 522 DUNHAM CLARK, WILMA LOUISE NOPTY 550 MULLEN, MICHAEL F NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, EDWIN L REP 550 MULLEN, REGAN N NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, JUDY A NOPTY 554 KIDWELL, MARISSA PAIGE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, JILL D DEM 554 LINDNER, MADELINE GRACE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, LAWRENCE B DEM 554 ROA, ALEX NOPTY 529 WITT, AARON C REP 529 WITT, RACHEL A REP CHATEAU PL MILFORD 45150 532 PASCALE, ANGELA W NOPTY 532 PASCALE, DOMINIC VINCENT NOPTY 2 STEVENS, JESSICA M NOPTY 532 PASCALE, MARK V NOPTY 2 #APT 1 CHURCHILL, REX -

An Encapsulation of Óðinn: Religious Belief and Ritual Practice Among The

An Encapsulation of Óðinn: Religious belief and ritual practice among the Viking Age elite with particular focus upon the practice of ritual hanging 500 -1050 AD A thesis presented in 2015 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Aberdeen by Douglas Robert Dutton M.A in History, University of Aberdeen MLitt in Scandinavian Studies, University of Aberdeen Centre for Scandinavian Studies The University of Aberdeen Summary The cult surrounding the complex and core Old Norse deity Óðinn encompasses a barely known group who are further disappearing into the folds of time. This thesis seeks to shed light upon and attempt to understand a motif that appears to be well recognised as central to the worship of this deity but one rarely examined in any depth: the motivations for, the act of and the resulting image surrounding the act of human sacrifice or more specifically, hanging and the hanged body. The cult of Óðinn and its more violent aspects has, with sufficient cause, been a topic carefully set aside for many years after the Second World War. Yet with the ever present march of time, we appear to have reached a point where it has become possible to discuss such topics in the light of modernity. To do so, I adhere largely to a literary studies model, focussing primarily upon eddic and skaldic poetry and the consistent underlying motifs expressed in conjunction with descriptions of this seemingly ritualistic act. To these, I add the study of legal and historical texts, linguistics and contemporary chronicles. -

The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia Religions : Ancient and Modern

RELIGION OF ANCIENT SCANDINAVIA LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO RELIGIONS ANCIENT AND MODERN THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT SCANDINAVIA RELIGIONS : ANCIENT AND MODERN. ANIMISM. By EDWARD CLODD, Author of The Story of Creation. PANTHEISM. By JAMES ALLAN SON PICTON, Author of The Religion of the universe. THE RELIGIONS OF ANCIENT CHINA. By Professor GILES, LL.D., Professor of Chinese in the University of Cambridge. THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT GREECE. By JANE HARRISON, Lecturer at Newnham College, Cambridge, Author of Prolegomena to Study of Greek Religion. ISLAM. By AMEER An SYED, M.A., C.I.E., late of H.M.'s High Court of Judicature in Bengal, Author of The Spirit of Iflam and The Ethics of Islam. MAGIC AND FETISHISM. By Dr. A. C. H ADDON, F.R.S., Lecturer on Ethnology at Cam- bridge University. THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT EGYPT. By Professor W. M. FLINDERS PETRIE, F.R.S. THE RELIGION OF BABYLONIA AND ASSYRIA. By THEOPHILUS G. PINCHES, late of the British Museum. EARLY BUDDHISM. By Professor RHYS DAVIDS, LL.D., late Secretary of The Royal Asiatic Society. HINDUISM. By Dr. L. D. BAR NEXT, of the Department of Oriental Printed Books and MSS. , British Museum. SCANDINAVIAN RELIGION. By WILLIAM A. CRAIGIE, Joint Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. CELTIC RELIGION. By Professor ANWYL, Professor of Welsh at University College, Aberystwyth. THE MYTHOLOGY OF ANCIENT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. By CHARLES SQUIRE, Author of The Mythology of the British Islands. JUDAISM By ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, Lecturer in Talmudic Literature in Cambridge University, Author of Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. -

Study Guide for School Days at the New Jersey Renaissance Faire

Study Guide for School Days at the New Jersey Renaissance Faire New Jersey Renaissance Faire 2016 NJRenFaire.com Facebook.com/NewJerseyRenFaire @NJRenFaire Facebook.com/NJRFedutainment 2 New Jersey Renaissance Faire WELCOME TO CROSSFORD “There be magic in these woods” The small village of Crossford is a typical English village of the 16th century. It has its farmers, its miller, its baker, oh, and its magical forest. Perhaps that is not typical, but it is ordinary for the citizens of Crossford, as it has been for decades. This forest is very old indeed. It has an energy all its own. It is the home to many fairies who hold court within its very boundaries. During times of magical power, which fall upon the solstices and equinoxes, the forest finds a person in need of direction, someone caught at a crossroads...and it brings him or her here to Crossford. This gateway transcends not only space but time itself. Where is Crossford? Crossford is a village in Northumberland, England. If it existed in 2016, it would stand approximately 20 miles southwest of Alnwick Castle, home of the Duke of Northumberland. However, as with all magical places, it has faded away with time. Northumberland Northumberland is a county in Northeast England. It shares a border with Scotland along its northern edge. Due to its geographical location, it has been the scene of many battles between England and Scotland. As evidence of its violent history, Northumberland has more castles than any other county in England. This includes the castles of Alnwick, Bamburgh, Dunstanburgh, Newcastle and Warkworth. -

Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature Hazel Carter School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 4 One of the most interesting and stimulating the themes, and especially in the use made of developments of recent years in African studies certain poetic techniques common to both. has been the discovery and rescue of the tradi- Compare, for instance, the following extracts, tional poetry of the Shona peoples, as reported the first from the clan praises of the Zebra 1 in a previous issue of this journal. In particular, (Tembo), the second from Beowulf, the great to anyone acquainted with Old English (Anglo- Old English epic, composed probably in the Saxon) poetry, the reading of the Shona poetry seventh century. The Zebra praises are com- strikes familiar chords, notably in the case of plimentary and the description of the dragon the nheternbo and madetembedzo praise poetry. from Beowulf quite the reverse, but the expres- The resemblances are not so much in the sion and handling of the imagery is strikingly content of the poetry as in the treatment of similar: Zvaitwa, Chivara, It has been done, Striped One, Njunta yerenje. Hornless beast of the desert. Heko.ni vaTemho, Thanks, honoured Tembo, Mashongera, Adorned One, Chinakira-matondo, Bush-beautifier, yakashonga mikonde Savakadzu decked with bead-girdles like women, Mhuka inoti, kana yomhanya Beast which, when it runs amid the mumalombo, rocks, Kuatsika, unoona mwoto kuti cheru And steps on them, you see fire drawn cfreru.2 forth. -

GIANTS and GIANTESSES a Study in Norse Mythology and Belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y

GIANTS AND GIANTESSES A study in Norse mythology and belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y. The family of giants plays apart of great importance in North Germanic mythology, as this is presented in the 'Eddas'. The phy sical environment as weIl as the race of gods and men owe their existence ultimately to the giants, for the world was shaped from a giant's body and the gods, who in turn created men, had de scended from the mighty creatures. The energy and efforts of the ruling gods center on their battles with trolls and giants; yet even so the world will ultimately perish through the giants' kindling of a deadly blaze. In the narratives which are concerned with human heroes trolls and giants enter, shape, and direct, more than other superhuman forces, the life of the protagonist. The mountains, rivers, or valleys of Iceland and Scandinavia are often designated with a giant's name, and royal houses, famous heroes, as weIl as leading families among the Icelandic settlers trace their origin to a giant or a giantess. The significance of the race of giants further is affirmed by the recor ding and the presence of several hundred giant-names in the Ice landic texts. It is not surprising that students of Germanic mythology and religion have probed the nature of the superhuman family. Thus giants were considered to be the representatives of untamed na ture1, the forces of sterility and death, the destructive powers of 1. Wolfgang Golther, Handbuch der germanischen Mythologie, Leipzig 1895, quoted by R.Broderius, The Giant in Germanic Tradition, Diss. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE.