Deficit of Ambition: How Germany's New Coalition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing Through Names and Titles in German

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4924–4932 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Doctor Who? Framing Through Names and Titles in German Esther van den Berg∗z, Katharina Korfhagey, Josef Ruppenhofer∗z, Michael Wiegand∗ and Katja Markert∗y ∗Leibniz ScienceCampus, Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany yInstitute of Computational Linguistics, Heidelberg University, Germany zInstitute for German Language, Mannheim, Germany fvdberg|korfhage|[email protected] fruppenhofer|[email protected] Abstract Entity framing is the selection of aspects of an entity to promote a particular viewpoint towards that entity. We investigate entity framing of political figures through the use of names and titles in German online discourse, enhancing current research in entity framing through titling and naming that concentrates on English only. We collect tweets that mention prominent German politicians and annotate them for stance. We find that the formality of naming in these tweets correlates positively with their stance. This confirms sociolinguistic observations that naming and titling can have a status-indicating function and suggests that this function is dominant in German tweets mentioning political figures. We also find that this status-indicating function is much weaker in tweets from users that are politically left-leaning than in tweets by right-leaning users. This is in line with observations from moral psychology that left-leaning and right-leaning users assign different importance to maintaining social hierarchies. Keywords: framing, naming, Twitter, German, stance, sentiment, social media 1. Introduction An interesting language to contrast with English in terms of naming and titling is German. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 198. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Donnerstag, 18.Oktober 2012 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Artikel 3 des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Achten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen (8. GWB-ÄndG) in der Ausschussfassung Drs. 17/9852 und 17/11053 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 543 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 77 Ja-Stimmen: 302 Nein-Stimmen: 241 Enthaltungen: 0 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 18. Okt. 12 Beginn: 19:24 Ende: 19:26 Seite: 1 CDU/CSU Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg.Name Ilse Aigner X Peter Altmaier X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Ernst-Reinhard Beck (Reutlingen) X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexander Dobrindt X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Hartwig Fischer (Göttingen) X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Herbert Frankenhauser X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Michael Frieser X Erich G. Fritz X Dr. Michael Fuchs X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Alexander Funk X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. Peter Gauweiler X Dr. -

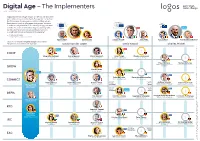

Digital Age – the Implementers 1 July – 31 December 2020

Digital Age – The Implementers 1 July – 31 December 2020 ”Digitalisation has a huge impact on the way we live, work and communicate. In some fields, Europe has to catch up – like for business to consumers – while in others we are frontrunners – such as in business to business. We have to make our single market fit for the digital age, we need Renew to make the most of artificial intelligence and big data, EPP S&D Europe we have to improve on cybersecurity and we have to work hard for our technological sovereignty.” — Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission Bjoern Seibert Ilze Juhansone Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle François Roux Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager will coordinate the agenda on a Europe fit for the digital age. Ursula von der Leyen David Sassoli Charles Michel Renew S&D Europe COMP Margrethe Vestager Kim Jørgensen Oliver Guersent Irene Tinagli Claudia Lindemann EPP Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General ECON Committee Chair ECON Secretariat Peter Altmaier Norbert Schultes Federal Minister of Economics Permanent Representation GROW and Energy Kerstin Jorna Greens/EFA Renew Director General Europe EPP Petra de Sutter Panos Konstantopoulos CONNECT IMCO Committee Chair IMCO Secretariat with ITRE with ITRE Thierry Breton Valère Moutarlier Roberto Viola Cristian- Peter Andreas Scheuer Stefanie Schröder Silviu Bușoi Traung Federal Minister of Transport Margrethe Commissioner -

Plenarprotokoll 19/117

Plenarprotokoll 19/117 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 117. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 16. Oktober 2019 Inhalt: Ausschussüberweisung . 14309 B Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- dere Aufgaben . 14311 C Gustav Herzog (SPD) . 14311 D Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregierung dere Aufgaben . 14312 A eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Grundgesetzes (Artikel 72, Gustav Herzog (SPD) . 14312 B 105 und 125b) Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Drucksache 19/13454 . 14309 C dere Aufgaben . 14312 B Oliver Luksic (FDP) . 14312 C Tagesordnungspunkt 2: Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregierung dere Aufgaben . 14312 C eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Oliver Luksic (FDP) . 14312 D Reform des Grundsteuer- und Bewertungs- rechts (Grundsteuer-Reformgesetz – Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- GrStRefG) dere Aufgaben . 14313 A Drucksachen 19/13453, 19/13713 . 14309 D Maik Beermann (CDU/CSU) . 14313 B Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Tagesordnungspunkt 3: dere Aufgaben . 14313 B Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregierung Ingrid Remmers (DIE LINKE) . 14313 D eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Änderung des Grundsteuergesetzes zur dere Aufgaben . 14314 A Mobilisierung von baureifen Grundstücken für die Bebauung Dr. Anna Christmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ Drucksache 19/13456 . 14309 D DIE GRÜNEN) . 14314 A Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- dere Aufgaben . 14314 B Tagesordnungspunkt 4: Dr. Anna Christmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ Befragung der Bundesregierung DIE GRÜNEN) . 14314 C Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- Dr. Helge Braun, Bundesminister für beson- dere Aufgaben . 14310 A dere Aufgaben . 14314 C Dr. Rainer Kraft (AfD) . -

Is There a Case for Rekindled Democracy Assistance in Central

Is there a case for rekindled democracy assistance in Central and Eastern Europe? International IDEA 25th Anniversary Europe Webinar Thursday 19 November, 11h00-13h00 Background In the two decades following the fall of the Berlin Wall, European and US governments undertook considerable efforts to support reforms for strengthening democratic governance in Central Europe. This support included efforts to foster multi-party politics and institutionalization of political parties, reforming public administration bodies, strengthening parliaments and judicial bodies, supporting independent media and civil society organizations – all vital pillars for a well-functioning democracy. After the Central and Eastern European countries joined the European Union, much of the international democracy assistance ended too, as western donors considered the region to have accomplished the necessary milestones in its democratic transformation and having passed the point of democratic no-return. Democracy’s checks-and-balances, they argued, had made a reversal toward non-democracy practically impossible. Throughout the last decade, this assumption of democratic irreversibility has come under increasing pressure. In 2019, the Global State of Democracy Indices measured that democracy in Central Europe had declined for the fourth consecutive year. In its 2020 report, Freedom House classified Hungary as a hybrid regime, having declined further from its earlier status of a semi-consolidated democracy, and thus breaking the standard of democratic conformity within the European Union, a multilateral body that itself aims to be a supporter of democracy worldwide. Civil society organizations, and more broadly civic space – which are conventionally considered key factors in building societal and institutional resilience against democratic backsliding – have become increasingly targeted. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

„Härtere Gangart“

Deutschland „Härtere Gangart“ Netzpolitik SPD-Fraktionschef Thomas Oppermann, 62, kündigt ein Gesetz gegen Fake News und Hasskommentare an und wirft Facebook vor, den demokratischen Diskurs zu untergraben. SPIEGEL: In Bocholt ist einer Ihrer Partei - nate Künast gerade wieder gezeigt hat. freunde gerade wegen Hassbotschaften ge - Das ist ein intransparentes Mysterium, gen ihn und seine Familie zurückgetreten. aber keine Rechtsschutzstelle. Ist das ein Einzelfall, oder wird das zum SPIEGEL: Melden wird nicht reichen. Renate politischen Alltag? Künast und die „Süddeutsche Zeitung“ ha - Oppermann: Ich habe Verständnis für seine ben sich vorige Woche direkt bei Facebook persönliche Entscheidung. Aber es ist eine über die sie betreffende Falschmeldung be - Niederlage für unseren freien, demokrati - schwert, und dennoch geschah drei Tage schen Diskurs, der auf Rede und Gegenre - lang nichts. Wie soll diese Rechtsschutz - de beruht. Wenn wir nicht aufpassen, wird stelle also funktionieren? er durch Lüge und Hass zerstört. Oppermann: Ich stelle mir das so vor: Wenn SPIEGEL: Anfeindungen und auch Lügen Betroffene ihre Rechtsverletzung dort sind in der Politik nichts Neues. Hat sich glaubhaft machen können und Facebook in der politischen Kommunikation wirklich nach entsprechender Prüfung die betroffe - etwas verändert? ne Meldung nicht unverzüglich binnen Oppermann: Ich sehe eine zunehmende Ver - 24 Stunden löscht, muss Facebook mit emp - rohung in der Gesellschaft insgesamt, für findlichen Bußgeldern bis zu 500 000 Euro S die es viele Gründe gibt. Aber die sozialen S rechnen. Und wenn die Betroffenen es E R P Medien tragen in besonderer Weise dazu wünschen, muss es zudem eine Richtigstel - N O I bei. Deshalb brauchen wir jetzt dringend T lung mit der gleichen Reichweite geben, C A / eine Verrechtlichung bei den Plattformen, und zwar spätestens nach 48 Stunden. -

Collective Identity in Germany: an Assessment of National Theories

James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 7 | Issue 1 2019-2020 Collective Identity in Germany: An Assessment of National Theories Sean Starkweather James Madison University Follow this and other works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/jmurj Recommended APA 7 Citation Starkweather, S. (2020). Collective identity in Germany: An assessment of national theories. James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal, 7(1), 36-48. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/jmurj/vol7/iss1/4 This full issue is brought to you for free and open access by JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in James Madison Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collective Identity in Germany An Assessment of National Theories Sean Starkweather “Köln stellt sich quer - Tanz die AfD” by Elke Witzig is licensed under CC BY-SA-4.0 Beginning in the 18th century, the question of what makes a nation has occupied a prominent place in German politics. From the national theories of the 18th-century German Romantics, who identified cultural and ethnic factors as being the key determinants, to modern civic nationalists and postnationalists, who point to liberal civic values and institutions, the importance of collective identity and how it is oriented has remained an important topic for German scholars and policymakers. Using survey research, I assess the accuracy and relevance of these theories in contemporary German society. I find that, contrary to the optimism of modern thinkers, German collective identity remains aligned with the national theories of the Romantics, resulting in ethnic discrimination and heightened fears over the loss of culture through external ideological and ethnic sources. -

Digital Society

B56133 The Science Magazine of the Max Planck Society 4.2018 Digital Society POLITICAL SCIENCE ASTRONOMY BIOMEDICINE LEARNING PSYCHOLOGY Democracy in The oddballs of A grain The nature of decline in Africa the solar system of brain children’s curiosity SCHLESWIG- Research Establishments HOLSTEIN Rostock Plön Greifswald MECKLENBURG- WESTERN POMERANIA Institute / research center Hamburg Sub-institute / external branch Other research establishments Associated research organizations Bremen BRANDENBURG LOWER SAXONY The Netherlands Nijmegen Berlin Italy Hanover Potsdam Rome Florence Magdeburg USA Münster SAXONY-ANHALT Jupiter, Florida NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA Brazil Dortmund Halle Manaus Mülheim Göttingen Leipzig Luxembourg Düsseldorf Luxembourg Cologne SAXONY DanielDaniel Hincapié, Hincapié, Bonn Jena Dresden ResearchResearch Engineer Engineer at at Marburg THURINGIA FraunhoferFraunhofer Institute, Institute, Bad Münstereifel HESSE MunichMunich RHINELAND Bad Nauheim PALATINATE Mainz Frankfurt Kaiserslautern SAARLAND Erlangen “Germany,“Germany, AustriaAustria andand SwitzerlandSwitzerland areare knownknown Saarbrücken Heidelberg BAVARIA Stuttgart Tübingen Garching forfor theirtheir outstandingoutstanding researchresearch opportunities.opportunities. BADEN- Munich WÜRTTEMBERG Martinsried Freiburg Seewiesen AndAnd academics.comacademics.com isis mymy go-togo-to portalportal forfor jobjob Radolfzell postings.”postings.” Publisher‘s Information MaxPlanckResearch is published by the Science Translation MaxPlanckResearch seeks to keep partners and -

Plenarprotokoll 19/85

Plenarprotokoll 19/85 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 85. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 13. März 2019 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin BMFSFJ ........................... 9977 B Befragung der Bundesregierung Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Norbert Müller (Potsdam) (DIE LINKE) .... 9977 C BMFSFJ ........................... 9973 C Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Johannes Huber (AfD) .................. 9974 B BMFSFJ ........................... 9977 D Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Paul Lehrieder (CDU/CSU) .............. 9978 A BMFSFJ ........................... 9974 B Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Johannes Huber (AfD) .................. 9974 C BMFSFJ ........................... 9978 B Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Stefan Schwartze (SPD) ................. 9978 C BMFSFJ ........................... 9974 D Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Dr. Silke Launert (CDU/CSU) ............ 9974 D BMFSFJ ........................... 9978 D Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Stefan Schwartze (SPD) ................. 9979 A BMFSFJ ........................... 9975 A Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Katja Suding (FDP). 9975 B BMFSFJ ........................... 9979 A Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Leni Breymaier (SPD) .................. 9979 B BMFSFJ ........................... 9975 B Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Katja Suding (FDP). 9975 C BMFSFJ ........................... 9979 C Dr. Franziska Giffey, Bundesministerin Sabine Zimmermann (Zwickau) -

Plenarprotokoll 19/139

Plenarprotokoll 19/139 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 139. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 15. Januar 2020 Inhalt: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17335 B nung . 17327 B Dr. Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 6 b und (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) . 17335 D 14 c . 17329 C Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17335 D Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 17329 D Ulrike Schielke-Ziesing (AfD) . 17336 A Feststellung der Tagesordnung . 17329 D Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17336 B Ulrike Schielke-Ziesing (AfD) . 17336 C Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17336 D Befragung der Bundesregierung Kai Whittaker (CDU/CSU) . 17337 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17330 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17337 A René Springer (AfD) . 17331 A Johannes Vogel (Olpe) (FDP) . 17337 C Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17331 B Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17337 D René Springer (AfD) . 17331 C Johannes Vogel (Olpe) (FDP) . 17338 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17331 C Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17338 A Antje Lezius (CDU/CSU) . 17332 A Michael Gerdes (SPD) . 17338 B Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17332 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17338 B Antje Lezius (CDU/CSU) . 17332 B Michael Gerdes (SPD) . 17338 D Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17332 C Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17338 D Johannes Vogel (Olpe) (FDP) . 17332 D Uwe Kekeritz (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) 17339 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17333 A Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17339 B Dr. Martin Rosemann (SPD) . 17333 B Uwe Kekeritz (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) 17339 D Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17333 C Hubertus Heil, Bundesminister BMAS . 17339 D Dr. Martin Rosemann (SPD) . -

Jens Spahn Die Biografie ® MIX Papier Aus Verantwor- Tungsvollen Quellen

Michael Bröcker Jens Spahn Die Biografie ® MIX Papier aus verantwor- tungsvollen Quellen ® www.fsc.org FSC C083411 © Verlag Herder GmbH, Freiburg im Breisgau 2018 Alle Rechte vorbehalten www.herder.de Satz: Barbara Herrmann, Freiburg Herstellung: CPI books GmbH, Leck Printed in Germany ISBN Print: 978-3-451-38336-2 ISBN E-Book: 978-3-451-81676-5 Inhalt 1. Vorwort .......................................... 7 2. »Er ist mir zu schnell groß geworden« – Kindheit und Jugend in Ottenstein ................ 13 3. »Ahaus – ausgesprochen radioaktiv« – wie die Castor-Gegner Spahn politisierten ......... 27 4. »Wir haben ein Wowereit-Problem« – erste Kandidatur, erste Widerstände ............... 46 5. »Ich kenn’ Sie doch aus der ›Aktuellen Stunde‹« – der Hinterbänkler in Berlin ....................... 59 6. »So klug wie anrüchig« – ein Freundschaftsdienst mit Folgen ........................................ 76 7. »Jemand wie Sie gehört aufgehängt« – das Renten-Drama ................................ 81 8. »Der kann ja Fachpolitik« – Aufstieg zum Gesundheitsexperten und neue politische Freunde . 85 9. »Ein Mann wie eine Walze« – Spahn, sein Mann und das Problem mit den Schwulen ................... 91 10. »Der Clübchengründer« – der Schweiger wird zum Netzwerker .............. 108 11. »Bevor es der Armin macht« – der Rivale im eigenen Land ....................... 139 12. »Jetzt erst recht« – der Übergangene putscht sich ins Präsidium ..................................... 150 5 13. »Eine Art Staatsversagen« – Geburt eines Merkel-Kritikers ..................... 169 14. »Welcome Deputy Finance Minister« – Spahns mächtiger Förderer ........................ 189 15. »Dann ziehe ich dir den Stecker« – der Zwei-Minuten-Eklat beim Parteitag ........... 201 16. »Denen überlassen wir das Land nicht« – die Anti-Merkel-Troika ........................... 206 17. »Die Mitte ist rechts von uns« – ein alter Richtungsstreit und eine neue Rivalin .... 216 18. »Der muss schon loyal sein« – endlich Minister ..