Political of Ethnic Identity in Multicultural Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2000 Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Rangoon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Fischer, Joseph, "Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries" (2000). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 803. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/803 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Narrating Seen and Unseen Worlds: Vanishing Balinese Embroideries Joseph Fischer Vanishing Balinese embroideries provide local people with a direct means of honoring their gods and transmitting important parts of their narrative cultural heritage, especially themes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These epics contain all the heroes, preferred and disdained personality traits, customary morals, instructive folk tales, and real and mythic historic connections with the Balinese people and their rich culture. A long ider-ider embroidery hanging engagingly from the eaves of a Hindu temple depicts supreme gods such as Wisnu and Siwa or the great mythic heroes such as Arjuna and Hanuman. It connects for the Balinese faithful, their life on earth with their heavenly tradition. Displayed as an offering on outdoor family shrines, a smalllamak embroidery of much admired personages such as Rama, Sita, Krisna and Bima reflects the high esteem in which many Balinese hold them up as role models of love, fidelity, bravery or wisdom. -

Analysis of Robusta Coffee Development in Way Kanan Regency (Study on Robusta Coffee Production Efficiency)

SSRG International Journal of Economics and Management Studies Volume 8 Issue 6, 53-54, June, 2021 ISSN: 2393 – 9125 /doi:10.14445/23939125/IJEMS-V8I6P108 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Analysis of Robusta Coffee Development in Way Kanan Regency (Study on Robusta Coffee Production Efficiency) Lucky Lanova1, Ida Budiarty2, Lies Maria Hamzah3 Master Program in Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business University of Lampung Prof. Dr. Soemantri Brodjonegoro No.1 Gedong Meneng, Lampung, Indonesia Received Date: 07 May 2021 Revised Date: 10 June 2021 Accepted Date: 18 June 2021 Abstract - This study aims to determine the level of land area of 137,875 ha. Meanwhile, South Sumatra production efficiency of people's coffee plantations in Province has an average production of 592.50 kg/ha with a Banjit District, Way Kanan Regency. The method used in land area of 206.018 ha. This shows that land area is not this research is a case study. Respondents consisted of red- the only main factor of production, so Lampung Province picked coffee farmers and random-picked coffee farmers. has the potential to be able to make a major contribution to The research was conducted in three villages in Banjit increasing robusta coffee production in Indonesia. district, namely Juku Batu Village, Menanga Siamang The distribution points of coffee plantations in Village and Rantau Temiang Village, Banjit District, Way Lampung are still dominated by the four main coffee- Kanan Regency. Determination of the location of the study producing districts. Among them are West Lampung, was carried out purposively with the consideration that Tanggamus, North Lampung, and Way Kanan Regencies. -

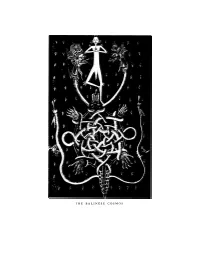

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: the Indonesian Example

geosciences Review Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: The Indonesian Example Mukhamad N. Malawani 1,2, Franck Lavigne 1,3,* , Christopher Gomez 2,4 , Bachtiar W. Mutaqin 2 and Danang S. Hadmoko 2 1 Laboratoire de Géographie Physique, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, UMR 8591, 92195 Meudon, France; [email protected] 2 Disaster and Risk Management Research Group, Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (B.W.M.); [email protected] (D.S.H.) 3 Institut Universitaire de France, 75005 Paris, France 4 Laboratory of Sediment Hazards and Disaster Risk, Kobe University, Kobe City 658-0022, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses the relations between the impacts of volcanic eruptions at multiple- scales and the related-issues of disaster-risk reduction (DRR). The review is structured around local and global impacts of volcanic eruptions, which have not been widely discussed in the literature, in terms of DRR issues. We classify the impacts at local scale on four different geographical features: impacts on the drainage system, on the structural morphology, on the water bodies, and the impact Citation: Malawani, M.N.; on societies and the environment. It has been demonstrated that information on local impacts can Lavigne, F.; Gomez, C.; be integrated into four phases of the DRR, i.e., monitoring, mapping, emergency, and recovery. In Mutaqin, B.W.; Hadmoko, D.S. contrast, information on the global impacts (e.g., global disruption on climate and air traffic) only fits Review of Local and Global Impacts the first DRR phase. -

Potential Tourism of Kambas National Park in Sukadana, Lampung Timur Regency Towards Regional Independence

th 4 ICITB POTENTIAL TOURISM OF KAMBAS NATIONAL PARK IN SUKADANA, LAMPUNG TIMUR REGENCY TOWARDS REGIONAL INDEPENDENCE Dwi Ismaryati ABSTRACT Indonesia is an archipelagic country that has natural resources that consist of oceans, sun, beaches and countries that allow it to be used as a source of foreign exchange. For regions that are blessed with exotic natural resources are expected to be able to contribute in providing foreign exchange for the region in order to achieve regional independence. The problems that occur how to market natural resources that consist of oceans, sun, beaches and abundant countries are assets that can provide a vision for local development. One effort that can be done is to make it a place. Market-driven sectors and industries. To market the items needed for all parties involved in management, government and society. This study aims to describe the tourism potential of the Way Kambas National Park in Sukadana, East Lampung Regency. The method used is descriptive method. The subject of the management research was set by 10 respondents. Techniques for exporting data, documentation and interviews. Data analysis uses a percentage table. The results showed that the Way Kambas National Park Tourism Object has a natural panoramic potential and socio-cultural potential. The total potential is 10 of the potential that there are 6 potentials that have been optimally developed and 4 potentials that have not been optimally optimized. Keywords: Potential, Tourism, Resources, Regional Independence INTRODUCTION Indonesia which is located on the equator has abundant diversity. This location causes Indonesia to have high biodiversity. Indonesia also has various types of ecosystems, such as aquatic ecosystems, freshwater ecosystems, peat swamps, mangrove forests, coral reefs, and coastal ecosystems. -

How Mount Agung's Eruption Can Create the World's Most Fertile Soil

How Mount Agung's eruption can create the world's most fertile soil https://theconversation.com/how-mount-agungs-eruption-can-create-the... Disiplin ilmiah, gaya jurnalistik How Mount Agung’s eruption can create the world’s most fertile soil Oktober 5, 2017 3.58pm WIB Balinese farmers with Mount Agung in the background. Areas with high volcanic activity also have some of the world’s most fertile farmlands. Reuters/Darren Whiteside Mount Agung in Bali is currently on the verge of eruption, and more than 100,000 Penulis people have been evacuated. However, one of us (Dian) is preparing to go into the area when it erupts, to collect the ash. This eruption is likely to be catastrophic, spewing lava and ashes at temperatures up to Budiman Minasny 1,250℃, posing serious risk to humans and their livelihoods. Ash ejected from volcano Professor in Soil-Landscape Modelling, not only affects aviation and tourism, but can also affect life and cause much nuisance to University of Sydney farmers, burying agricultural land and damaging crops. However, in the long term, the ash will create world’s most productive soils. Anthony Reid Emeritus Professor, School of Culture, 1 of 5 10/7/2017, 5:37 AM How Mount Agung's eruption can create the world's most fertile soil https://theconversation.com/how-mount-agungs-eruption-can-create-the... History and Language, Australian National University Dian Fiantis Professor of Soil Science, Universitas Andalas Alih bahasa Bahasa Indonesia English Read more: Bali’s Mount Agung threatens to erupt for the first time in more than 50 years While volcanic soils only cover 1% of the world’s land surface, they can support 10% of the world’s population, including some areas with the highest population densities. -

Hypocenter Relocation of Volcanic Earthquake at Agung Vulcano

The 4th International Seminar on Science and Technology 95 August 9th 2018, Postgraduate Program Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Surabaya, Indonesia Hypocenter Relocation of Volcanic Earthquake at Agung Vulcano Reni Agustiani1, Bagus J. Santosa1, Yasa Suparman2, Devi K. Syahbana2,Gazali Rachman3 Abstract―Agung Volcano is a stratovolcano located in the Agung considered as one of the most dangerous volcanoes area of Karangasem regency of Bali and is in the northwest- of Indonesia because of the densely populated surrounding. southeast fault alignment with Batur, Abang and Seroja Based on this, it is necessary to analyze Mount Agung's Volcano. The existence of this alignment allegedly related to the seismic data. Thus, in this study, an earthquake hypocenter fracture in the northwest of the island of Bali. The eruption of relocation was conducted to determine the location of the Agung Volcano recorded on November 25th, 2017 was a significant danger for people living around it. Therefore, it is source of the earthquake that caused the eruption. Besides, necessary to monitor the activity of Agung Volcano. The method also obtained of both the 1D earth velocity model and used in this study is the relocation of volcanic earthquake station correction. sources to determine the location of the source of the earthquake which caused an increase in Mount activity. Hypocenter II. COUPLED HYPOCENTER VELOCITY MODEL relocation was carried out on 138 earthquake events during October 2017-January 2018 using the Coupled Velocity- The arrival time of a seismic wave generated by an Hypocenter method. Hypocenter was obtained at a depth of less earthquake is a nonlinear function of the station coordinates than 10 km under sea level with an RMS value <0.3 seconds, (s), the hypocentral parameter (origin time (t) and and this is thought to have a flow of magma fluid through the geographic coordinates (x, y, z, t)), and velocity field (m). -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 69 3rd International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management, and Social Science (TEAMS 2018) The Economic Impact of Mount Agung Eruption on Bali Tourism Putu Indah Rahmawati Trianasari A.A.Ngr.Yudha Martin Hotel Department, Economic Faculty Hotel Department, Economic Faculty Hotel Department, Economic Faculty Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Indonesia Indonesia Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— This study aims to analyse the economic impact of I. Introduction Mount Agung eruption in 2017 on Bali tourism. This study uses a qualitative research approach. Data was collected Bali is a small island that very vulnerable to the through interviews with hotel managers and tourism impacts of climate change and natural disasters ((Stocker et stakeholders in Bali. The research sample was determined by al., 2013) stated with great confidence - at least 90% the true purposive sampling technique. The results show that most possibility - that small islands "are very vulnerable to the respondents said that they experienced drastic income decline impacts of climate change and natural disasters such as sea after the closure of Ngurah Rai airport due to Mount Agung level rise, floods, landslides, high winds, earthquakes and eruption. The decrease in hotel room occupancy in December other extreme events ". In addition, Mason (2012) argues that 2018 even reaches 20-30%. This is very significant because Bali's excessive dependence on the tourism industry can lead December is usually peak season in Bali and hotels can to an economic crisis in the future. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume -� Focus� On� The� Legong� Dance� Costume

Print ISSN 1229-6880 Journal of the Korean Society of Costume Online ISSN 2287-7827 Vol. 67, No. 4 (June 2017) pp. 38-57 https://doi.org/10.7233/jksc.2017.67.4.038 An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume - Focus on the Legong Dance Costume - Langi, Kezia-Clarissa · Park, Shinmi⁺ Master Candidate, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University⁺ (received date: 2017. 1. 12, revised date: 2017. 4. 11, accepted date: 2017. 6. 16) ABSTRACT1) Traditional costume in Indonesia represents identity of a person and it displays the origin and the status of the person. Where culture and religion are fused, the traditional costume serves one of the most functions in rituals in Bali. This research aims to analyze the charac- teristics of Balinese costumes by focusing on the Legong dance costume. Quantitative re- search was performed using 332 images of Indonesian costumes and 210 images of Balinese ceremonial costumes. Qualitative research was performed by doing field research in Puri Saba, Gianyar and SMKN 3 SUKAWATI(Traditional Art Middle School). The paper illus- trates the influence and structure of Indonesian traditional costume. As the result, focusing on the upper wear costume showed that the ancient era costumes were influenced by animism. They consist of tube(kemben), shawl(syal), corset, dress(terusan), body painting and tattoo, jewelry(perhiasan), and cross. The Modern era, which was shaped by religion, consists of baju kurung(tunic) and kebaya(kaftan). The Balinese costume consists of the costume of participants and the costume of performers.