Victorian Heroines and the Creation of Domestic Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

G. Robert Stange

Recent Studies in Nineteenth-Century English Literature G. ROBERT STANGE THE FIRST reaction of the surveyor of the year's work in the field of the nineteenth century is dismay at its sheer bulk. The period has obviouslybecome the most recent playground of scholars and academic critics. One gets a sense of settlers rushing toward a new frontier, and at 'times regrets irra- tionally ithe simpler, quieter days. At first glance the massive acocumulation of intellectual labor which I have undertaken to describe seems to display no pattern whatsoever, no evidence of noticeable trends. Yet, to the persistent gazer certain characteristics ultimately reveal themselves. There is a discernible tendency? for example, to lapply the concepts of po'st Existential theology to the work of the Romantic poets; and in general these poets are now being approached with an intellectual excitement which is very different from the diffuse "romantic" enthusiasm of twenty or thirty years ago. It must also be said that the Victorian novelists continue to come into 'their own. lThe kind of serious attention 'thiatit is now assumed Dickens and George Eliot require was a rare thing a decade ago; it is undoubtedly good that this rigorous- thiough sometimes over-solemn-analysis is now being extended to 'some of 'the lesser novelists of the period. It is also still to be noted as an unaccountable oddity th'at reliable editions of even the most important nineteenth-century authors are not always available. Of the novelists 'only Jane Austen has so far 'been critically edited. The Victorian poets, with the exception of Arnold, are in textual chaos, and ;though critical editions of Arnold's and Mill's prose are forthcoming, other prose writers have not 'been much heeded. -

Why Does Daniel Deronda's Mother Live in Russia? Catherine Brown

Why Does Daniel Deronda’s Mother Live In Russia? Catherine Brown Eliot, like Daniel, wanted to avoid “a merely English attitude in studies” (Daniel Deronda [DD] 155). She educated herself to a degree which her critics struggle to match about Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Bohemia, and Palestine -- but not about Russia. In her relative lack of interest in this country she was typical of her own country and time; Lewes’s acquaintance Laurence Oliphant noted in his 1854 account of his travels in Russia that “the scanty information which the public already possesses has been of such a nature as to create an indifference towards acquiring more” (vii). Apart from the works of Turgenev, Eliot is not known to have read any Russian literature, even though Gogol’, Dostoevskii, and Tolstoi would have been available to her in French translation. The take-off decade for English translations of Russian literature started in the year of her death (Brewster 173). Why, then, having hitherto mentioned the country in her fiction only as a source of linseed in The Mill on the Floss, did she choose Russia as the location of Leonora Alcharisi’s second marriage, self-imposed exile from singing and Europe, and emotional and physical decline? Of course, Russia is not simply imposed on Alcharisi by Eliot; she also chose it for herself (this article will treat her and her second husband as though they were real people, in the interests of historical investigation). After the death of her first husband she had suitors of many countries, including Sir Hugo Mallinger, and there is no reason to think that by the age of thirty her options had narrowed to a single man. -

I-IOW to CI-IOOSE a HUSBAND 'I-J "-Lopkins You Will Pick a Good Husband If You Decide for MARY ALDEN Finds It to Return Or

~bitauo 6unba!' Vtribune ''-a!' 20,1928 5 HOW TO CHOOSE A • f}31V' Do RIS WEBSTER.a.nd HUSBAND - By Doris Webster AND Mary Alden Hopkins (Continued from page jO'UT.) KEY NUMBER 25. to be in trouble. Remember how difficult 0. woman I-IOW TO CI-IOOSE A HUSBAND 'I-J "-lOPKINS You will pick a good husband if you decide for MARY ALDEN finds it to return or. exchange a man after she has married him. yourself. You are in danger of being unduly in- '. fluenced by some one who speaks firmly but not KEY NUMBER 5. wisely to you. Quietly select your own hats, hUI!- Can you ha ve harmonious business or social rela- You may not be a large woman physically, but, band, and cooking utensils. Give in to others if There' s Just One tions with uncongenial people? you are mentally. You are the kind that runs or- you wish on politics, religion, and such matters. Have you' changed your views on politics, re- ganizatione efficiently and sees to it that every You will make a good wife and a happy one for ligion, or morals within the Iast five years? one in the organization knows his duty and does it. 'almost any man who shows you a good deal of Man for You, Whether You will not change, so you must be careful to attention. GROUP 4. marry the right man-one who admires your ap- KEY NUMBER 34. Do you desire an "addre88 of distinction "t preciation of the really worth while things in life You are by no means ready to marry, for at pres- and who will 110t find your missionary spirit trying. -

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Author(s): Caroline Wilkinson Source: George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2016), pp. 25-42 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/georelioghlstud.68.1.0025 Accessed: 16-09-2018 23:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies This content downloaded from 73.121.242.252 on Sun, 16 Sep 2018 23:56:41 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Caroline Wilkinson University of Tennessee In both her epic poem The Spanish Gypsy and her final novel Daniel Deronda, Eliot drew upon kabbalistic concepts of the heavens through the characters of Jewish mystics. In the later novel, Eliot moved the mystic, Mordecai, from the narrative’s periphery to its center. This change, symbolically equated within the novel to a shift from geocentricism to heliocentrism, affects time in Daniel Deronda both in terms of plot and historical focus. -

The Midlands Essential Entertainment Guide

Staffordshire Cover - July.qxp_Mids Cover - August 23/06/2014 16:43 Page 1 STAFFORDSHIRE WHAT’S ON WHAT’S STAFFORDSHIRE THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE STAFFORDSHIRE ISSUE 343 JULY 2014 JULY ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 343 JULY 2014 ROBBIE WILLIAMS SWINGS INTO BRUM RHYS DARBY return of the Kiwi comedian PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART THE GRUFFALO journey through the deep dark wood in Stafford... FUSE FESTIVAL showcasing the region’s @WHATSONSTAFFS WWW.WHATSONLIVE.CO.UK @WHATSONSTAFFS talent at Beacon Park Antiques For Everyone (FP-July).qxp_Layout 1 23/06/2014 14:00 Page 1 Contents- Region two - July.qxp_Layout 1 23/06/2014 12:42 Page 1 June 2014 Editor: Davina Evans INSIDE: [email protected] 01743 281708 Editorial Assistants: Ellie Goulding Brian O’Faolain [email protected] joins line-up for 01743 281701 Wireless Festival p45 Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Sales & Marketing: Jon Cartwright [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Subscriptions: Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Scooby-Doo Managing Director: spooky things a-happening Paul Oliver [email protected] in Wolverhampton p27 01743 281711 Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan [email protected] 01743 281710 Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell Chris Atherton Accounts Administrator Julia Perry Wicked - the award-winning musical -

Beauty Revealed in Silence: Ways of Aesthetization in Hanibal (Nbc 2013-2015)

The Journal of Kitsch, Camp and Mas Culture The Journal of Kitsch, Camp and Mass Culture Volume 1 / 2017 BEAUTY REVEALED IN SILENCE: WAYS OF AESTHETIZATION IN HANIBAL (NBC 2013-2015) Adam Andrzejewski University of Warsaw, Institute of Philosophy, [email protected] Beauty Revealed in Silence: Ways of Aesthetization in Hannibal (NBC 2013–2015) BEAUTY REVEALED IN SILENCE: WAYS OF AESTHETIZATION IN HANIBAL (NBC 2013-2015) Adam Andrzejewski TV shows are an unquestionable part of our modern life. We watch them compulsively, discuss them, love some of them, hate others. More and more frequently, they are becoming the subject of theoretical analysis, mainly due to the ever-changing form, poetics or the issues dealt with. The purpose of this modest paper is to analyse the possible ways of aesthetization of the fictional universe in the popular TV series Hannibal (NBC 2013-2015). My goal is to answer not only the question of which of the aesthetization models, i.e. the theatralization of life or the aesthetics of everyday life is better suited for the conceptualization of Hannibal, but also to determine the conceptual relationships between these two aesthetic phenomena. The essay has the following structure. In §1, I will analyse and clarify the definition of the concept of a performance. Then, in §2, I will describe the concept of theatrical work, in particular, I will analyse its constitutive properties. In §3, I will characterise the phenomena of aesthetization of life through its theatralization and I will indicate the links which exist be- tween aesthetic properties and dramatic properties. At the end of the text, in §4, I will explore the possibility of treating the theatralization of life as a form of everyday aesthetics using story- lines taken from Hannibal. -

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist

JULIA CARTA Hair Stylist and Make-Up Artist www.juliacarta.com PRESS JUNKETS/PUBLICITY EVENTS Matt Dillon - Grooming - WAYWARD PINES - London Press Junket Jeremy Priven - Grooming - BAFTA Awards - London Christian Bale - Grooming - AMERICAN HUSTLE - BAFTA Awards - London Naveen Andrews - Grooming - DIANA - London Press Junket Bruce Willis and Helen Mirren - Grooming - RED 2 - London Press Conference Ben Affleck - Grooming - ARGO - Sebastián Film Festival Press Junket Matthew Morrison - Grooming - WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU’RE EXPECTING - London Press Junket Clark Gregg - Grooming - THE AVENGERS - London Press Junket Max Iron - Grooming - RED RIDING HOOD - London Press Junket and Premiere Mia Wasikowska - Hair - RESTLESS - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Elle Fanning - Make-Up - SUPER 8 - London Press Junket Jamie Chung - Hair & Make-Up - SUCKERPUNCH - London Press Junket and Premiere Steve Carell - Grooming - DESPICABLE ME - London Press Junket and Premiere Mark Strong and Matthew Macfayden - Grooming - Cannes Film Festival, Press Junket and Premiere Michael C. Hall - Grooming - DEXTER - London Press Junket Jonah Hill - Grooming - GET HIM TO THE GREEK - London Press Junket and Premiere Laura Linney - Hair and Make-Up - THE BIG C - London Press Junket Ben Affleck - Grooming - THE TOWN - London and Dublin Press and Premiere Tour Andrew Lincoln - Grooming - THE WALKING DEAD - London Press Junket Rhys Ifans - Grooming - NANNY MCPHEE: THE BIG BANG (RETURNS) - London Press Junket and Premiere Bruce Willis - Grooming - RED - London -

George Eliot on Stage and Screen

George Eliot on Stage and Screen MARGARET HARRIS* Certain Victorian novelists have a significant 'afterlife' in stage and screen adaptations of their work: the Brontes in numerous film versions of Charlotte's Jane Eyre and of Emily's Wuthering Heights, Dickens in Lionel Bart's musical Oliver!, or the Royal Shakespeare Company's Nicholas Nickleby-and so on.l Let me give a more detailed example. My interest in adaptations of Victorian novels dates from seeing Roman Polanski's film Tess of 1979. I learned in the course of work for a piece on this adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel Tess of the D'Urbervilles of 1891 that there had been a number of stage adaptations, including one by Hardy himself which had a successful professional production in London in 1925, as well as amateur 'out of town' productions. In Hardy's lifetime (he died in 1928), there was an opera, produced at Covent Garden in 1909; and two film versions, in 1913 and 1924; together with others since.2 Here is an index to or benchmark of the variety and frequency of adaptations of another Victorian novelist than George Eliot. It is striking that George Eliot hardly has an 'afterlife' in such mediations. The question, 'why is this so?', is perplexing to say the least, and one for which I have no satisfactory answer. The classic problem for film adaptations of novels is how to deal with narrative standpoint, focalisation, and authorial commentary, and a reflex answer might hypothesise that George Eliot's narrators pose too great a challenge. -

George Eliot

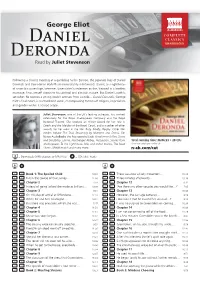

George Eliot COMPLETE CLASSICS Daniel UNABRIDGED Deronda Read by Juliet Stevenson Following a chance meeting at a gambling hall in Europe, the separate lives of Daniel Deronda and Gwendolen Harleth are immediately intertwined. Daniel, an Englishman of uncertain parentage, becomes Gwendolen’s redeemer as she, trapped in a loveless marriage, finds herself drawn to his spiritual and altruistic nature. But Daniel’s path is set when he rescues a young Jewish woman from suicide… Daniel Deronda, George Eliot’s final novel, is a remarkable work, encompassing themes of religion, imperialism and gender within its broad scope. Juliet Stevenson, one of the UK’s leading actresses, has worked extensively for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre. She received an Olivier Award for her role in Death and the Maiden at the Royal Court, and a number of other awards for her work in the filmTruly, Madly, Deeply. Other film credits include The Trial, Drowning by Numbers and Emma. For Naxos AudioBooks she has recorded Lady Windermere’s Fan, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion, Stories from Total running time: 36:06:33 • 28 CDs Shakespeare, To the Lighthouse, Bliss and Other Stories, The Road View our catalogue online at Home, Middlemarch and many more. n-ab.com/cat = Downloads (M4B chapters or MP3 files) = CDs (disc–track) 1 1-1 Book 1: The Spoiled Child 10:08 25 4-5 There was now a lively movement… 13:28 2 1-2 But in the course of that survey… 12:08 26 4-6 Three minutes afterwards… 13:18 3 1-3 Chapter 2 7:58 27 -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

CHOOSING of a BRIDE Los Angeles, CA March 29, 1965 Vol

SERMONS BY REV. W. M. BRANHAM "... in the days of the voice... " Rev. 10:7 CHOOSING OF A BRIDE Los Angeles, CA March 29, 1965 Vol. 65, No. 22 Introduction The compiler of the work, A. David Mamalis, recognized that all sermons are public domain, belonging to the people. There is NO claim of copyright on the sermon text. The copyright applies to the verso side of the title page; and only in the design of the classification system of all interrelations of the text to the volume, volume number, paging, paragraphing, or any identification of the text by utilizing the copyrighted classification system. The purpose of such copyright is to preserve the work for the design of indexes, and other support reference materials, for the study of the last days' message. Permission is given for anyone to print and distribute this booklet, provided it is done free of charge. Any changes made to the electronic file that this booklet is distributed in constitute a violation of international copyright law. Instructions for printing this booklet in its proper format can be found in the Printing FAQ on our website at www.thefreeword.com. We pray that the Holy Spirit will make the messages alive to those who are called to be conformed to the image of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. www.thefreeword.com Licensed Internet Publisher If you would like more information on the ministry of Rev. William M. Branham, download additional sermons or have questions of a spiritual nature, please refer to our website at: www.thefreeword.com Copyright by A.