Section 3.0 THEMATIC ANALYSIS and ASSESSMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Changing Garden Styles and Practices in Post War Suburban

13' 1.qt I '; l- MITCHAM'S FRONT GARDENS I t- i' L I I I I I I A STUDY OF CHANGING GARDEN STYLES AND PRACTICES iI I IN POST WAR SUBURBAN ADEI,\IDE by Elizabeth Margaret Caldicott, B.A. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography University of Adelaide March 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PACE (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS (ii) LIST OF TABLES (ix) LIST OF MAPS (x) LIST OF FICURES (xi) LIST OF PIATES (xiii) ABSTRACT (xv) DECIARATION (xvii) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (xviii) 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background to and aims of the investigation 2 1.1.1 Part I - Ideas for garden studies 2 1.1.2 Part II - The detailed case study 7 1.2 lssues to be investigated 7 1.3 Mitcham City Council - the fieldwork case study area 8 PART I IDEAS FOR GARDEN STUDIES 2. Ideas for garden studies - a review of literature 11 2.1 Academic papers 11 2.2 Urban and environmental commentaries 18 2.3 Historians 19 2.4 Historical popular gardening literature 20 2.4.1 Early South Australian gardening guides 22 2.4.2 Specialist writers 24 2.4.3 Early works on Australian native flora 26 (i i) Page 2.5 Early Australian gardens 28 2.6 Towards an Australian garden ethos 30 2.7 Summary 36 3 A history of garden design to the present 37 3.1 Cardens in history 37 3.1.1 The ancient gardens 39 3.1.2 The Renaissance 40 3.1.3 The English garden tradition 41 3.1.4 Victoriana - the picturesque garden 42 3.1.5 North American gardens 43 3.1.6 Present day linl<s with the past 45 3.2 The Botanic Cardens of Adelaide 45 3.3 Modern Australian suburban gardens 47 3.3.1 Adelaide's early colonial gardens 49 3.3.2 1900-1945 gardens in Adelaide 50 3.3.3 Post World War ll gardens - 1945-1970 51 3.3.4 i 970s to the present 53 3.4 The cultivation of Australian native plants 54 3.5 The rise and demise of the 'all native' garden 56 3.6 Conclusions and Hypotheses 1 and 2 57 4. -

A Phylogeny of the Flowering Plant

American Journal of Botany 87(2): 273±292. 2000. A PHYLOGENY OF THE FLOWERING PLANT FAMILY APIACEAE BASED ON CHLOROPLAST DNA RPL16 AND RPOC1 INTRON SEQUENCES: TOWARDS A SUPRAGENERIC CLASSIFICATION OF SUBFAMILY APIOIDEAE1 STEPHEN R. DOWNIE,2,4 DEBORAH S. KATZ-DOWNIE,2 AND MARK F. W ATSON3 2Department of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA; and 3Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, Scotland, UK The higher level relationships within Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) subfamily Apioideae are controversial, with no widely acceptable modern classi®cation available. Comparative sequencing of the intron in chloroplast ribosomal protein gene rpl16 was carried out in order to examine evolutionary relationships among 119 species (99 genera) of subfamily Apioideae and 28 species from Apiaceae subfamilies Saniculoideae and Hydrocotyloideae, and putatively allied families Araliaceae and Pittosporaceae. Phylogenetic analyses of these intron sequences alone, or in conjunction with plastid rpoC1 intron sequences for a subset of the taxa, using maximum parsimony and neighbor-joining methods, reveal a pattern of relationships within Apioideae consistent with previously published chloroplast DNA and nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS based phylogenies. Based on consensus of relationship, seven major lineages within the subfamily are recognized at the tribal level. These are referred to as tribes Heteromorpheae M. F. Watson & S. R. Downie Trib. Nov., Bupleureae Spreng. (1820), Oenantheae Dumort. (1827), Pleurospermeae M. F. Watson & S. R. Downie Trib. Nov., Smyrnieae Spreng. (1820), Aciphylleae M. F. Watson & S. R. Downie Trib. Nov., and Scandiceae Spreng. (1820). Scandiceae comprises subtribes Daucinae Dumort. (1827), Scan- dicinae Tausch (1834), and Torilidinae Dumort. (1827). -

System Garden Masterplan, Melbourne University 2018

SYstem GARDEN LANDSCAPE MASTERPLAN STAGE 4 - MASTERPLAN FINAL REPORT 8th MARCH 2018 landscape architecture and GLAS urban design CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 3 HistorY OF THE SYstem GARDEN 4 THE GARDEN TODAY 5 KEY ISSUES FACING THE SYstem GARDEN 6 Masterplan VISION 7 K EY VALUES 8 THE SYstem GARDEN AND OC21 9 VISION: A BOTANIC GARDEN FOR THE CAMPUS 10 MASTERPLAN PRINCIPLES 11 THE SYstem GARDEN MASTERPLAN 13 strategic INITIATIVES 15 BotanicAL DivERSiTy - SuB-cLASS PLANTiNG GuiDELiNES 16 INTERPRETATION StrateGY 17 UNIVERSITY HISTORY 18 INDIGENOUS ConnecTION 19 SUSTAINABILITY 20 MATERIALS PALETTE 21 MATERiALS PALETTE - LiGHTiNG AND PoWER 22 MATERiALS PALETTE - coNSoLiDATiNG SERvicES 23 FURNITURE 24 Access 25 ART AND EVENTS IN THE GARDEN 26 Masterplan ELEMENTS 27 master PLAN ELEMENTS 28 PERIMETER PATH AND EDGE SPACES 29 SYstem GARDEN GATEs 30 ENTRy AvENuES - BiZARRE SENTRiES 31 THE FORMAL GARDEN 32 WETLAND cANAL 37 THE INFORMAL GARDEN 38 COURTYARD GARDENS 43 rainforest GARDEN 44 FERN AND LICHEN COURTYARD 45 APOTHECARY GARDEN 47 RESEARCH GARDENS 48 implementation STAGING 50 APPENDIX 1: costing 55 APPENDIX 2: CONSULTANT REPORTS 57 EXecUTIVE SUMMARY IntroDUction The System Garden is a special space. Originally laid out in 1856 by Professor Frederick McCoy and The Core values, are key to the current and future operation of the Parkville campus, they have a • indigenous connection: the System Garden provides indigenous interpretation through Edward LaTrobe Bateman, it is a botanic garden configured specifically for learning. It provides a direct link to the University’s OC21 strategy (Our Campus in the 21st Century) and will drive the the Billibellary’s walk and stop within the System Garden. -

Handbook-Victoria.Pdf

VICTORIA, by theGrace of God, of the United Kingdona of Great Britain and IreZandQueen, Defender of the Paith. Our trusty and well-beloved the Honorable GEORGE DAVIDLANGRIDGE, a Member of the Executive Council of Our Colony of Victoria, and a - Member of the Legislative Assembly of Our said Colony; HENRYGYLES TURNER,Esquire, J.P., Acting President of the Chamber of Commerce ; ISAACJACOBS, Esquire, President of the Victorian Chamber of Manufactures ; JOHN GEORGEBARRETT, Esquire, President of the Melbourne Trades’ Hall Council ; JAMES COOPERSTEWART, Esquire, an Alderman of the City of Melbourne; and HENRYMEAKIN, Esquire, a Councillor of the Town of Geelong, 5 GREETING- WHEREASit has been notified to us that an Exhibition of the Arts, Industries, Resources, and Manners of New Zealand, Australia, and the other Countries and Colonies in the Southern Pacific will open at Dunedin,in Our Colony of New Zealand, in themonth of November next, in celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Foundation of Our said Colony of New Zealand, ?nd*whereas it is in every respect desirable that Our Colony of Victoria sh9u.l’d,be duly represented at the same and that a Commission should be appointed to devise and carry out such measures as may be necessary to secure the effectual exhibition thereat òf fitting specimens of the Arts, Industries, and Resources of Our said Colony of Victoria: Now KNOW YE that We, reposing great trust and confidence in your knowledge and ability, have constituted and appointed, and by these presents do constitute and appoint you -

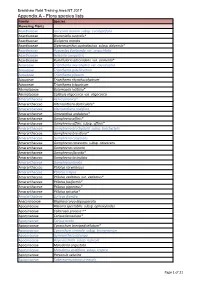

Report-NT-Bradshaw-Appendix A

Bradshaw Field Training Area NT 2017 Appendix A - Flora species lists Family Species Flowering Plants Acanthaceae Avicennia marina subsp. eucalyptifolia Acanthaceae Brunoniella australis* Acanthaceae Dicliptera armata Acanthaceae Dipteracanthus australasicus subsp. dalyensis* Acanthaceae Hypoestes floribunda var. angustifolia Acanthaceae Nelsonia campestris Acanthaceae Rostellularia adscendens var. clementii* Aizoaceae Trianthema oxycalyptra var. oxycalyptra Aizoaceae Trianthema patellitectum Aizoaceae Trianthema pilosum Aizoaceae Trianthema rhynchocalyptrum Aizoaceae Trianthema triquetrum Alismataceae Butomopsis latifolia* Alismataceae Caldesia oligococca var. oligococca Amaranthaceae Aerva javanica^ Amaranthaceae Alternanthera denticulata* Amaranthaceae Alternanthera nodiflora Amaranthaceae Amaranthus undulatus* Amaranthaceae Gomphrena affinis* Amaranthaceae Gomphrena affinis subsp. affinis* Amaranthaceae Gomphrena brachystylis subsp. brachystylis Amaranthaceae Gomphrena breviflora* Amaranthaceae Gomphrena canescens Amaranthaceae Gomphrena canescens subsp. canescens Amaranthaceae Gomphrena connata Amaranthaceae Gomphrena flaccida* Amaranthaceae Gomphrena lacinulata Amaranthaceae Gomphrena lanata Amaranthaceae Ptilotus corymbosus Amaranthaceae Ptilotus crispus Amaranthaceae Ptilotus exaltatus var. exaltatus* Amaranthaceae Ptilotus fusiformis* Amaranthaceae Ptilotus giganteus* Amaranthaceae Ptilotus spicatus* Amaranthaceae Surreya diandra Anacardiaceae Blepharocarya depauperata Apocynaceae Alstonia spectabilis subsp. ophioxyloides Apocynaceae -

Images from the Outback

Images from the Outback Item Type Article Authors Johnson, Matthew B. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 26/09/2021 00:25:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/555917 Outback Johnson 21 species of Acacia are found in Australia (Orchard and Images from the Outback - Wilson, 200 I ), though only a relatively small percentage of Notes on Plants of the Australian these occur in desert habitats. Acacia woodlands can be dense or open, and are sometimes mixed with grasses including Dry Zone spinifex. Spinifex grasslands, dominated by species of Plectraclme and Triodia (p. 27) are widespread on sandy plains as well as rocky slopes and sand dunes. These grasses, Matthew B. Johnson many with stiff, rolled leaves that end in a sharp point, form Desert Legume Program clumps or tussocks. Fires are frequent in some spinifex The University of Arizona communities and the woody plants that grow there are 2120 East Allen Road necessarily fire-adapted. Chenopod shrublands are low stature communities composed of numerous shrubs and Tucson, AZ 85719 herbaceous plants in the Chenopodiaceae. Less widespread [email protected] than acacia woodland and spinifex grassland, this type of Yegetation is found mostly in the southern parts ofAustralia's A visit to the Sydney area of Australia in 1987 tirst sparked arid zone (Van Oosterzee, 1991 ). Beyond the deserts lie my interest in seeing more of the Island Continent and in semi-arid woodlands dominated by species of Euca~vptus particular, the extensive dry regions of the country. -

IX Apiales Symposium

IX Apiales Symposium Abstract Book 31 July – 2 August 2017 The Gold Coast Marina Club Guangzhou, China Compiled and edited by: Alexei Oskolski Maxim Nuraliev Patricia Tilney Introduction We are pleased to announce that the Apiales IX Symposium will be held from 31 July to 2 August 2017 at the The Gold Coast Marina Club in Guangzhou, China. This meeting will continue the series of very successful gatherings in Reading (1970), Perpignan (1977), St. Louis (1999), Pretoria (2003), Vienna (2005), Moscow (2008), Sydney (2011) and Istanbul (2014), where students of this interesting group of plants had the opportunity to share results of recent studies. As with the previous symposia, the meeting in Guangzhou will focus on all research fields relating to the systematics and phylogeny of Apiales (including morphology, anatomy, biogeography, floristics), as well as to ecology, ethnobotany, pharmaceutical and natural products research in this plant group. Organizing Commettee Chairman: Alexei Oskolski (Johannesburg – St. Petersburg) Vice-Chairman: Maxim Nuraliev (Moscow) Scientific Committee: Yousef Ajani (Tehran) Emine Akalin (Istanbul) Stephen Downie (Urbana) Murray Henwood (Sydney) Neriman Özhatay (Istanbul) Tatiana Ostroumova (Moscow) Michael Pimenov (Moscow) Gregory Plunkett (New York) Mark Schlessman (Poughkeepsie) Krzysztof Spalik (Warsaw) Patricia Tilney (Johannesburg) Ben-Erik van Wyk (Johannesburg) 2 Program of the IX Apiales Symposium 31 July 2017 Lobby of the Gold Coast Marina Club 14.00 – 18.00. Registration of participants. "Shi fu zai" room (4th floor of the Gold Coast Marina Club) 19.00 – 21.00. Welcome party 1 August 2017 Meeting room (5th floor of the Gold Coast Marina Club) Chair: Dr. Alexei Oskolski 9.00 – 9.20. -

Pittosporaceae)

Plant Div. Evol. Vol. 128/3–4, 491–500 E Stuttgart, September 17, 2010 Comparative bark anatomy of Bursaria, Hymenosporum and Pittosporum (Pittosporaceae) By Maya Nilova and Alexei A. Oskolski With 15 figures and 1 table Abstract Nilova, M. & Oskolski, A.A.: Comparative bark anatomy of Bursaria, Hymenosporum and Pittospo- rum (Pittosporaceae) — Plant Div. Evol. 128: 491–500. 2010. — ISSN 1869-6155. Bark anatomy in 3 species of Bursaria, 9 species of Pittosporum, and in the single species of mono- typic genus Hymenosporum (Pittosporaceae) was examined. The members of these three genera resemble Araliaceae, Myodocarpaceae and Apiaceae in the occurrence of axial secretory canals in cortex and secondary phloem, the pattern of alternating zones in secondary phloem, and the absence of fibres in this tissue. We therefore confirm a relationship between Pittosporaceae and other Apiales (van Tieghem 1884, Dahlgren 1989, Takhtajan 1997, Plunkett et al. 1996, 2004) rather than its tradi- tional placement into Rosales (Cronquist 1981). Hymenosporum differs markedly from Bursaria and Pittosporum in the presence of primary phloem fibres, in the cortical (vs subepidermal) initiation of the periderm and in the occurrence of numerous (more than 25) sieve areas on compound sieve plates. These features confirm the isolated position of Hymenosporum within Pittosporaceae, as suggested both by traditional taxonomy and gross morphology (Cayzer et al. 2000) and by molecular phyloge- netics (Chandler et al. 2007). Keywords: Pittosporaceae, Hymenosporum, Bursaria, bark anatomy, phylogenetics. Introduction Pittosporaceae is a small plant family with 9 genera and roughly 200–240 species. Eight of these genera are restricted to Australia or extended into nearby Malaysia, whereas the large genus Pittosporum is widely distributed within the tropical and sub- tropical zones of the Old World (Chandler et al. -

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Ficus Rubiginosa Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species Profile Ficus Rubiginosa. Available

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Ficus rubiginosa Ficus rubiginosa System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Urticales Moraceae Common name little leaf fig (English), rusty fig (English), rusty-leaved fig (English), Port Jackson fig (English) Synonym Ficus australis , Willd., Sp. Pl. 4: 1138 (1806) Mastosuke rubiginosa , (Desf. ex Vent.) Raf., Sylva Tellur. 59 (1838) Urostigma rubiginosum , (Desf. ex Vent.) Gasp. Nov. Gen. Fic. 7 (1884) Urostigma leichhardtii , Miq. J. Bot. Neerl. 1: 235 (1861); Ficus leichhardtii , (Miq.) Miq., Ann. Mus. Bot. Lugduno-Batavum 3: 268 (1867); Ficus platypoda , var. leichhardtii (Miq.) R.F.J. Hend., Austrobaileya 4: 119 (1993). Ficus leichhardtii , var. angustata Miq., Ann. Mus. Bot. Lugduno- Batavum 3: 268 (1867); Ficus platypoda , var. angustata (Miq.) Corner, Gard. Bull. Singapore 21: 27 (1965). Ficus platypoda , var. mollis Benth., Fl. Austral. 6: 170 (1873). Ficus platypoda , var. subacuminata Benth., Fl. Austral. 6: 170 (1873). Ficus platypoda , var. petiolaris Benth., Fl. Austral. 6: 170 (1873); Ficus obliqua , var. petiolaris (Benth.) Corner, Gard. Bull. Singapore 17: 402 (1960). Ficus rubiginosa , var. lucida Maiden, Forest Fl. New South Wales 1: 10 (1902). Ficus rubiginosa , var. variegata Guilf., Austral. Pl. 178 (1911). Ficus macrophylla , var. pubescens F.M. Bailey, Queensland Agric. J. 26: 316 (1911). Ficus baileyana , Domin, Biblioth. Bot. 89: 12 (1921). Ficus shirleyana , Domin, Biblioth. Bot. 89: 12 (1921). Similar species Ficus macrophylla, Ficus obliqua, Ficus watkinsiana Summary Ficus rubiginosa is potentially a broad, spreading, evergreen tree that is native to eastern Australia. It usually establishes as a hemiepiphyte or lithophyte, developing into a large strangler or rock-breaker on favourable sites, or remaining a small epiphytic or lithophytic shrub on very harsh sites. -

Lose the Plot: Cost-Effective Survey of the Peak Range, Central Queensland

Lose the plot: cost-effective survey of the Peak Range, central Queensland. Don W. Butlera and Rod J. Fensham Queensland Herbarium, Environmental Protection Agency, Mt Coot-tha Botanic Gardens, Mt Coot-tha Road, Toowong, QLD, 4066 AUSTRALIA. aCorresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract: The Peak Range (22˚ 28’ S; 147˚ 53’ E) is an archipelago of rocky peaks set in grassy basalt rolling-plains, east of Clermont in central Queensland. This report describes the flora and vegetation based on surveys of 26 peaks. The survey recorded all plant species encountered on traverses of distinct habitat zones, which included the ‘matrix’ adjacent to each peak. The method involved effort comparable to a general flora survey but provided sufficient information to also describe floristic association among peaks, broad habitat types, and contrast vegetation on the peaks with the surrounding landscape matrix. The flora of the Peak Range includes at least 507 native vascular plant species, representing 84 plant families. Exotic species are relatively few, with 36 species recorded, but can be quite prominent in some situations. The most abundant exotic plants are the grass Melinis repens and the forb Bidens bipinnata. Plant distribution patterns among peaks suggest three primary groups related to position within the range and geology. The Peak Range makes a substantial contribution to the botanical diversity of its region and harbours several endemic plants among a flora clearly distinct from that of the surrounding terrain. The distinctiveness of the range’s flora is due to two habitat components: dry rainforest patches reliant upon fire protection afforded by cliffs and scree, and; rocky summits and hillsides supporting xeric shrublands. -

Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research

Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research • Milan S. • Milan Stankovic Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research Edited by Milan S. Stankovic Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Plants www.mdpi.com/journal/plants Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research Special Issue Editor Milan S. Stankovic MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Milan S. Stankovic University of Kragujevac Serbia Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Plants (ISSN 2223-7747) from 2017 to 2018 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/plants/special issues/medicinal plants). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03928-118-3 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03928-119-0 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Trinidad Ruiz Tellez.´ c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Medicinal Plants and Natural Product Research” ................... -

Recent Advances in Understanding Apiales and a Revised Classification

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector South African Journal of Botany 2004, 70(3): 371–381 Copyright © NISC Pty Ltd Printed in South Africa — All rights reserved SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY ISSN 0254–6299 Recent advances in understanding Apiales and a revised classification GM Plunkett1*, GT Chandler1,2, PP Lowry II3, SM Pinney1 and TS Sprenkle1 1 Department of Biology, Virginia Commonwealth University, PO Box 842012, Richmond, Virginia 23284-2012, United States of America 2 Present address: Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, North Carolina 28403-5915, United States of America 3 Missouri Botanical Garden, PO Box 299, St Louis, Missouri 63166-0299, United States of America; Département de Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Case Postale 39, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris CEDEX 05, France * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 23 August 2003, accepted in revised form 18 November 2003 Despite the long history of recognising the angiosperm Apiales, which includes a core group of four families order Apiales as a natural alliance, the circumscription (Apiaceae, Araliaceae, Myodocarpaceae, Pittosporaceae) of the order and the relationships among its constituent to which three small families are also added groups have been troublesome. Recent studies, howev- (Griseliniaceae, Torricelliaceae and Pennantiaceae). After er, have made great progress in understanding phylo- a brief review of recent advances in each of the major genetic relationships in Apiales. Although much of this groups, a revised classification of the order is present- recent work has been based on molecular data, the ed, which includes the recognition of the new suborder results are congruent with other sources of data, includ- Apiineae (comprising the four core families) and two ing morphology and geography.