Homerocentos and the Ontology of Christ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/166705 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. Epic Architecture: Architectural Terminology and the Cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem in the Epics of Juvencus and Proba* Roald DIJKSTRA Soon after Constantine’s seizure of power, splen- pear as classical as possible while treating biblical did basilicas were built in Rome and the Holy content, he omitted many references to Jewish Land.1 Constantine had created the conditions culture, including topographical details.4 He necessary for the emergence of a rich Christian was anxious not to alienate his Rome-oriented architecture. At the same time, Christian po- audience in a poem that was a daunting liter- etry now also fully emerged. The first classiciz- ary innovation. Words referring to the world of ing yet openly Christian poets – Juvencus and architecture, however, are certainly not absent Proba – took the Roman epic tradition and in from his epic.5 Most of them can be explained particular Vergil as their main literary examples. by remarks in the biblical text of the gospels: In this tradition – and also in Rome’s national they either denote (groups of) dwellings, graves, epic the Aeneid – monuments played an impor- ‘spiritual’ buildings outside the world of earthly tant role.2 Moreover, the Aeneid ultimately told realia, or function as building metaphors. the story of the foundation of Rome. -

The Reader and the Poet

THE READER AND THE POET THE TRANSFORMATION OF LATIN POETRY IN THE FOURTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron David Pelttari August 2012 i © 2012 Aaron David Pelttari ii The Reader and the Poet: The Transformation of Latin Poetry in the Fourth Century Aaron Pelttari, Ph.D. Cornell University 2012 In Late Antiquity, the figure of the reader came to play a central role in mediating the presence of the text. And, within the tradition of Latin poetry, the fourth century marks a turn towards writing that privileges the reader’s involvement in shaping the meaning of the text. Therefore, this dissertation addresses a set of problems related to the aesthetics of Late Antiquity, the reception of Classical Roman poetry, and the relation between author and reader. I begin with a chapter on contemporary methods of reading, in order to show the ways in which Late Antique authors draw attention to their own interpretations of authoritative texts and to their own creation of supplemental meaning. I show how such disparate authors as Jerome, Augustine, Servius, and Macrobius each privileges the work of secondary authorship. The second chapter considers the use of prefaces in Late Antique poetry. The imposition of paratextual borders dramatized the reader’s involvement in the text. In the third chapter, I apply Umberto Eco’s idea of the open text to the figural poetry of Optatianus Porphyrius, to the Psychomachia of Prudentius, and to the centos from Late Antiquity. -

The Gospel 'According to Homer and Virgil': Cento and Canon by Karl Olav Sandnes

489 Karl Olav Sandnes, The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon (Novum Testamentum Supplements 138; Leiden: Brill, 2011). Pp. xii + 280. € 106. ISBN 978-90-041-871-84 MARCIN KOWALSKI BibAn 3 (2013) 489-493 Institute of Biblical Studies, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin address: Aleje Racławickie 14, 20-950 Lublin, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] he Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon by Karl TOlav Sandnes (KOS) is the fruit of the author’s interest in the early Chris- tian’s relationship to the literary culture surrounding it . Karl Olav Sandnes is Professor of New Testament at the Free Faculty in Oslo . His interest in the influence of Homer upon the early Christian writers arose, as we come to know from the Preface, from the critical encounter with the ideas and publications by Dennis R . MacDonnald . It resulted first in the article “Imi- tatio Homeri? An Appraisal of Dennis R . MacDonald’s ‘Mimesis Criticism’”, JBL 124 (2005) 715-732, and subsequently in the book The Challenge of Homer: School, Pagan Poets, and Early Christianity (LNTS 400; London: T&T Clark, 2009) . The purpose of the present book first of all lies in getting the readers familiar with the ancient centos . Secondly, the author tries to assess to what extent the Greek centos of Homer and the Latin centos of Virgil can help us in understanding the process of the composition of the Gospels . The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’ consists of the preface and seven chapters, the last of which offers a concise summary of the main points stated by KOS in the present publication . -

Research Bank Divine Simplicity in the Theology of Irenaeus Simons, Jonatán C

Research Bank PhD Thesis Divine simplicity in the theology of Irenaeus Simons, Jonatán C. Simons, Jonatán C. (2021). Divine simplicity in the theology of Irenaeus [PhD Thesis]. Australian Catholic University Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry https://doi.org/10.26199/acu.8w716 This work is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International DIVINE SIMPLICITY IN THE THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS Submitted by Jonatán C. Simons MA and MDiv A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry Faculty of the Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University 2020 Declaration or Statement of Authorship and Sources This thesis contains no material that has been extracted in whole in or part from a thesis that I have submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Statement of Appreciation or Dedication First, I want to thank Australian Catholic University for granting me the Postgraduate Award which funded my studies. I also want to thank the members of the Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry in Melbourne, especially the members of the Modes of Knowing Research team: Dr. Sarah Gador-Whyte, Dr. Michael Hanaghan, Dr. Dawn LaValle Norman, and Dr. Jonathan Zecher.They answered questions, helped with translations, and treated me as a colleague and a friend. I also want to thank Dr. Jonathan Zecher and Dr. Ben Edsall for their helpful feedback at the candidature milestone seminars. -

Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Book Culture Manuscripts of The

Books before print – manuscripts – were modified continuously Kwakkel This volume explores the production and use of medieval throughout the medieval period. Focusing on the ninth and Studies in Medieval and manuscripts that contain classical Latin texts. Six experts in the field twelfth centuries, this volume explores such material changes address a range of topics related to these manuscripts, including as well as the varying circumstances under which handwritten how classical texts were disseminated throughout medieval society, books were produced, used and collected. An important theme is of the Latin Classics Manuscripts how readers used and interacted with specific texts, and what these Renaissance Book Culture the relationship between the physical book and its users. Can we books look like from a material standpoint. This collection of reflect on reading practices through an examination of the layout essays also considers the value of studying classical manuscripts as of a text? To what extent can we use the contents of libraries to a distinct group, and demonstrates how such a collective approach understand the culture of the book? The volume explores such Manuscripts of the Latin can add to our understanding of how classical works functioned in issues by focusing on a broad palette of texts and through a medieval society. Focusing on the period 800-1200, when classical detailed analysis of manuscripts from all corners of Europe. works played a crucial role in the teaching of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectics, this volume investigates how classical Latin texts were Classics 800-1200 Erik Kwakkel teaches at Leiden University, where he directs the copied, used, and circulated in both discrete and shared contexts. -

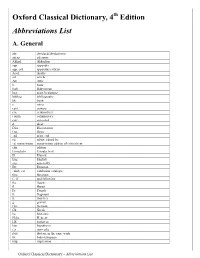

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE ROLES OF IMPERIAL WOMEN IN THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE (AD 306-455) Belinda Washington Doctorate of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2015 Signed Declaration I hereby declare that that this thesis is entirely my own composition and work. It contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree or professional degree. Belinda Washington 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................. 7 MAIN TEXTS USED AND LISTS OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TABLES -

Karl Olav Sandnes, the Gospel 'According to Homer and Virgil'

[JGRChJ 8 (2011–12) R81-R85] BOOK REVIEW Karl Olav Sandnes, The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon (NovTSup, 138; Leiden: Brill, 2011). v + 280 pp. Hbk. US$146.00 (€103.00). Karl Sandnes takes an in-depth look at a fourth- and fifth-century Christian practice that involved rewriting Gospel narratives in the tradition of the classical writers Virgil and Homer. Such a work is called a cento (pl. centones), and is defined by Sandnes as ‘a pastiche of lines or quotes from a classical text’ (p. 3). This discussion aims to answer the question of whether the first-century Gospels could have been written in a similar style. Similar proposals have recently been made by Claremont scholar Dennis R. MacDonald and Harvard’s Mari- anne Palmer-Bonz, who suggest that the Gospel of Mark, as well as Luke–Acts, were modeled after the epics of Virgil and Homer. These theories suggest a new type of literary criticism called mimesis criti- cism. MacDonald describes this methodology as an alternative to form criticism, and suggests that certain stories contained within the Gospels originated from the process of imitating the Homeric and Virgilian epics and not pre-Gospel traditions. Chapter 1 introduces the idea of mimesis criticism and makes the case that the epic poets were widely available in the first century for Christians through written word, art and live performances. Chapter 2 discusses various popular pedagogical exercises in the classical world, which included paraphrasis, mimesis, emulatio and synkrisis. It is in the tradition of these exercises that the centones were written. -

Early Christian Women Writers: the Interesting Lives and Works of Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia

UNIVERSITY OF BUCHAREST DEPARTMENT UNESCO CHAIR ON THE STUDY OF INTER-CULTURAL AND INTER-RELIGIOUS EXCHANGES MASTER „ COMMUNICATION AND INTERCULTURAL MANAGEMENT ” EARLY CHRISTIAN WOMEN WRITERS: THE INTERESTING LIVES AND WORKS OF FALTONIA BETITIA PROBA AND ATHENAIS-EUDOCIA Authors: Cătălina M ărmureanu Gianina Cernescu Laura Lixandru Scientific coordinator: Prof. univ. dr. Sylvie Hauser-Borel Bucharest 2008 Contents Early Christian Women Writers: Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia / 3 Faltonia Betitia Proba (c.320-370 AD) / 4 The Empress Eudocia /Athenais-Eudocia/Aelia Eudokia (c.400-460 AD) / 11 Conclusion / 17 Bibliography / 18 Note on the Writers / 19 2 Early Christian Women Writers: Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia In the past two decades scholarship regarding the participation of women in the formation of Christian religion has witnessed an almost complete revision. As women historians have entered the field in record numbers, new perspectives and questions have been brought to the forefront. At the same time, the continuous exploration for evidence of women’s presence in previously neglected texts, have resulted in exciting new findings. For example, up to recent years only a few names were synonymous with this topic: Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, his disciple and the first witness to the resurrection, as well as Mary and Martha, the sisters who offered him hospitality in Bethany. 1 Today, primary sources along with historiography, have unveiled that women, despite facing restrictive opportunities to exercise their intellectual and literal skills, have bequeathed the church with a respectable literary and intellectual legacy. Religion transgressed the rigid boundaries enshrined by sex roles, thus permitting women to take interest, study, and most importantly participate in Christian theology. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ EUDOCIA: THE MAKING OF A HOMERIC CHRISTIAN A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 by Brian Patrick Sowers B.A., University of Evansville, 2001 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Peter van Minnen ii ABSTRACT With over 3,400 lines of poetry and no single monograph dedicated to her literary productions, Aelia Eudocia is an understudied poet. This project, the first of its kind, explores Eudocia's three poems as a unified whole and demonstrates how they exemplify the literary and cultural concerns of the fifth century. Since her poems are each apparently unique, I approach them first in isolation and tease out their social background, literary dependencies, and possible interpretive strategies for them before painting a broader picture of Eudocia's literary contribution. The first of her surviving poems is a seventeen line epigraphic poem from the bath complex at Hammat Gader, which acclaims the bath's furnace for its service to the structure's clients but, at the same time, illustrates the religious competition that surrounded late antique healing cults, of which therapeutic springs were part. Next is the Homeric cento, which borrows and reorders lines from the Iliad and Odyssey to retell parts of the biblical narrative. -

Structures of Epic Poetry Structures of Epic Poetry Volume III: Continuity

Structures of Epic Poetry Structures of Epic Poetry Volume III: Continuity Edited by Christiane Reitz and Simone Finkmann ISBN 978-3-11-049200-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049259-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049167-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953831 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Eric Naujoks (Rostock), Dr. Jörn Kobes (Gutenberg) Cover image: Carrara Marble Quarries, © Wulf Liebau (†), Photograph: Courtesy of Irene Liebau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Christiane Reitz and Simone Finkmann The origin, tradition, and reinvention of epic structures – a short introduction | 1 Johannes Haubold Poetic form and narrative theme in early Greek and Akkadian epic | 7 Simon Zuenelli The transformation of the epic genre in Late Antiquity | 25 Berenice Verhelst Greek biblical epic: Nonnus’ Paraphrase and Eudocia’s Homerocentones | 53 Christoph Schubert Between imitation and transformation: the (un)conventional use of epic structures in the Latin biblical poetry of Late Antiquity | 79 Martin Bažil Epic forms and structures in late antique Vergilian centos | 135 Kristoffel Demoen and Berenice Verhelst The tradition of epic poetry in Byzantine literature | 175 Wim Verbaal Medieval epicity and the deconstruction of classical epic | 211 Christian -

The Old Testament in the New. Ethel M. Wood Lecture Delivered

C.H. Dodd, The Old Testament in the New. The Ethel M. Wood Lecture delivered before the University of London on 4 March, 1952. London: The Athlone Press, 1952. pp.21. The Old Testament in the New C. H. Dodd Professor Emeritus in the University of Cambridge The Ethel M. Wood Lecture delivered before the University of London on 4 March, 1952 [p.3] Any reader of the Bible who is accustomed to the salutary, if now somewhat old-fashioned, practice of using an apparatus of marginal references cannot fail to be aware of the immense extent to which writers of the New Testament quote passages from the Old, or make unavowed but unmistakable allusions to such passages. Sometimes the appositeness of a quotation will set the reader at once upon a profitable train of thought; sometimes, but by no means always. From time to time he will have an uneasy feeling that there are links of association which elude him, which indeed may perhaps never have existed except in the fancy of an individual writer. When this is so, further study is discouraged. And the whole mass of quotations and allusions is so unwieldy and seemingly so amorphous that it is not easy to discover any system in it. Our present task is to seek for some clue to the intention, and the methods, of New Testament writers which may perhaps help us to see the relevance, not of this or that quotation, but, in some measure, of their use of the Old Testament in general. We must no doubt allow for the possibility that in some places we have before us nothing more than the rhetorical device of literary allusion, still common enough, and even more common in the period when the New Testament was produced.