CENTONES: Recycled Art Or the Embodiment of Absolute Intertextuality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/166705 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. Epic Architecture: Architectural Terminology and the Cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem in the Epics of Juvencus and Proba* Roald DIJKSTRA Soon after Constantine’s seizure of power, splen- pear as classical as possible while treating biblical did basilicas were built in Rome and the Holy content, he omitted many references to Jewish Land.1 Constantine had created the conditions culture, including topographical details.4 He necessary for the emergence of a rich Christian was anxious not to alienate his Rome-oriented architecture. At the same time, Christian po- audience in a poem that was a daunting liter- etry now also fully emerged. The first classiciz- ary innovation. Words referring to the world of ing yet openly Christian poets – Juvencus and architecture, however, are certainly not absent Proba – took the Roman epic tradition and in from his epic.5 Most of them can be explained particular Vergil as their main literary examples. by remarks in the biblical text of the gospels: In this tradition – and also in Rome’s national they either denote (groups of) dwellings, graves, epic the Aeneid – monuments played an impor- ‘spiritual’ buildings outside the world of earthly tant role.2 Moreover, the Aeneid ultimately told realia, or function as building metaphors. the story of the foundation of Rome. -

The Reader and the Poet

THE READER AND THE POET THE TRANSFORMATION OF LATIN POETRY IN THE FOURTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron David Pelttari August 2012 i © 2012 Aaron David Pelttari ii The Reader and the Poet: The Transformation of Latin Poetry in the Fourth Century Aaron Pelttari, Ph.D. Cornell University 2012 In Late Antiquity, the figure of the reader came to play a central role in mediating the presence of the text. And, within the tradition of Latin poetry, the fourth century marks a turn towards writing that privileges the reader’s involvement in shaping the meaning of the text. Therefore, this dissertation addresses a set of problems related to the aesthetics of Late Antiquity, the reception of Classical Roman poetry, and the relation between author and reader. I begin with a chapter on contemporary methods of reading, in order to show the ways in which Late Antique authors draw attention to their own interpretations of authoritative texts and to their own creation of supplemental meaning. I show how such disparate authors as Jerome, Augustine, Servius, and Macrobius each privileges the work of secondary authorship. The second chapter considers the use of prefaces in Late Antique poetry. The imposition of paratextual borders dramatized the reader’s involvement in the text. In the third chapter, I apply Umberto Eco’s idea of the open text to the figural poetry of Optatianus Porphyrius, to the Psychomachia of Prudentius, and to the centos from Late Antiquity. -

The Gospel 'According to Homer and Virgil': Cento and Canon by Karl Olav Sandnes

489 Karl Olav Sandnes, The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon (Novum Testamentum Supplements 138; Leiden: Brill, 2011). Pp. xii + 280. € 106. ISBN 978-90-041-871-84 MARCIN KOWALSKI BibAn 3 (2013) 489-493 Institute of Biblical Studies, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin address: Aleje Racławickie 14, 20-950 Lublin, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] he Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon by Karl TOlav Sandnes (KOS) is the fruit of the author’s interest in the early Chris- tian’s relationship to the literary culture surrounding it . Karl Olav Sandnes is Professor of New Testament at the Free Faculty in Oslo . His interest in the influence of Homer upon the early Christian writers arose, as we come to know from the Preface, from the critical encounter with the ideas and publications by Dennis R . MacDonnald . It resulted first in the article “Imi- tatio Homeri? An Appraisal of Dennis R . MacDonald’s ‘Mimesis Criticism’”, JBL 124 (2005) 715-732, and subsequently in the book The Challenge of Homer: School, Pagan Poets, and Early Christianity (LNTS 400; London: T&T Clark, 2009) . The purpose of the present book first of all lies in getting the readers familiar with the ancient centos . Secondly, the author tries to assess to what extent the Greek centos of Homer and the Latin centos of Virgil can help us in understanding the process of the composition of the Gospels . The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’ consists of the preface and seven chapters, the last of which offers a concise summary of the main points stated by KOS in the present publication . -

Research Bank Divine Simplicity in the Theology of Irenaeus Simons, Jonatán C

Research Bank PhD Thesis Divine simplicity in the theology of Irenaeus Simons, Jonatán C. Simons, Jonatán C. (2021). Divine simplicity in the theology of Irenaeus [PhD Thesis]. Australian Catholic University Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry https://doi.org/10.26199/acu.8w716 This work is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International DIVINE SIMPLICITY IN THE THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS Submitted by Jonatán C. Simons MA and MDiv A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry Faculty of the Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University 2020 Declaration or Statement of Authorship and Sources This thesis contains no material that has been extracted in whole in or part from a thesis that I have submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Statement of Appreciation or Dedication First, I want to thank Australian Catholic University for granting me the Postgraduate Award which funded my studies. I also want to thank the members of the Institute of Religion and Critical Inquiry in Melbourne, especially the members of the Modes of Knowing Research team: Dr. Sarah Gador-Whyte, Dr. Michael Hanaghan, Dr. Dawn LaValle Norman, and Dr. Jonathan Zecher.They answered questions, helped with translations, and treated me as a colleague and a friend. I also want to thank Dr. Jonathan Zecher and Dr. Ben Edsall for their helpful feedback at the candidature milestone seminars. -

Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Book Culture Manuscripts of The

Books before print – manuscripts – were modified continuously Kwakkel This volume explores the production and use of medieval throughout the medieval period. Focusing on the ninth and Studies in Medieval and manuscripts that contain classical Latin texts. Six experts in the field twelfth centuries, this volume explores such material changes address a range of topics related to these manuscripts, including as well as the varying circumstances under which handwritten how classical texts were disseminated throughout medieval society, books were produced, used and collected. An important theme is of the Latin Classics Manuscripts how readers used and interacted with specific texts, and what these Renaissance Book Culture the relationship between the physical book and its users. Can we books look like from a material standpoint. This collection of reflect on reading practices through an examination of the layout essays also considers the value of studying classical manuscripts as of a text? To what extent can we use the contents of libraries to a distinct group, and demonstrates how such a collective approach understand the culture of the book? The volume explores such Manuscripts of the Latin can add to our understanding of how classical works functioned in issues by focusing on a broad palette of texts and through a medieval society. Focusing on the period 800-1200, when classical detailed analysis of manuscripts from all corners of Europe. works played a crucial role in the teaching of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectics, this volume investigates how classical Latin texts were Classics 800-1200 Erik Kwakkel teaches at Leiden University, where he directs the copied, used, and circulated in both discrete and shared contexts. -

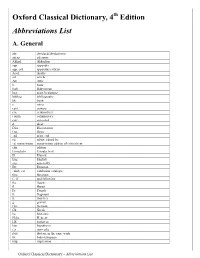

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE ROLES OF IMPERIAL WOMEN IN THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE (AD 306-455) Belinda Washington Doctorate of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2015 Signed Declaration I hereby declare that that this thesis is entirely my own composition and work. It contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree or professional degree. Belinda Washington 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................. 7 MAIN TEXTS USED AND LISTS OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TABLES -

Karl Olav Sandnes, the Gospel 'According to Homer and Virgil'

[JGRChJ 8 (2011–12) R81-R85] BOOK REVIEW Karl Olav Sandnes, The Gospel ‘According to Homer and Virgil’: Cento and Canon (NovTSup, 138; Leiden: Brill, 2011). v + 280 pp. Hbk. US$146.00 (€103.00). Karl Sandnes takes an in-depth look at a fourth- and fifth-century Christian practice that involved rewriting Gospel narratives in the tradition of the classical writers Virgil and Homer. Such a work is called a cento (pl. centones), and is defined by Sandnes as ‘a pastiche of lines or quotes from a classical text’ (p. 3). This discussion aims to answer the question of whether the first-century Gospels could have been written in a similar style. Similar proposals have recently been made by Claremont scholar Dennis R. MacDonald and Harvard’s Mari- anne Palmer-Bonz, who suggest that the Gospel of Mark, as well as Luke–Acts, were modeled after the epics of Virgil and Homer. These theories suggest a new type of literary criticism called mimesis criti- cism. MacDonald describes this methodology as an alternative to form criticism, and suggests that certain stories contained within the Gospels originated from the process of imitating the Homeric and Virgilian epics and not pre-Gospel traditions. Chapter 1 introduces the idea of mimesis criticism and makes the case that the epic poets were widely available in the first century for Christians through written word, art and live performances. Chapter 2 discusses various popular pedagogical exercises in the classical world, which included paraphrasis, mimesis, emulatio and synkrisis. It is in the tradition of these exercises that the centones were written. -

Homerocentos and the Ontology of Christ

„Analecta Cracoviensia” 50 (2018), s. 11–22 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/acr.3281 Fr. Szymon Drzyżdżyk The Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow Homerocentos and the Ontology of Christ Homerocentons are poetic pieces from the 4th and 5th centuries written in Greek, which attempt to present the Gospel in the language of Homer. Similar to the Homeric poems, they were written with dactylic hexameter, and constructed in such a way that the individual verses of the various books of the Iliad and Odyssey were so connected that their contents corresponded to the Gospel. They emerged in the epoch of heated Christological disputes, and even now it is worth taking a closer look at them to investigate to what extent they record the discussions of the fourth and fifth centuries regarding the identity of Jesus Christ. In the first decade of the 21st century, Rocco Schembra issued five critical manuscripts of the Homerocentos.1 Recently the first detailed commentaries2 on these works have been produced as well as several significant monographs devoted to their analysis both from the linguistic perspective and from the theological point of view.3 The relatively short time since the release of this critic of the Homerocentos reveals a number of issues that are worth investigating. One of these is the ontology of Jesus Christ. This topic is important because it is connected with the issue of the Hellenization of Christianity, which is still being discussed. It is worth analyzing these works from the perspective of the ontology of Jesus Christ. The analysis of all five manuscripts would certainly 1 Homerocentones, ed. -

Early Christian Women Writers: the Interesting Lives and Works of Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia

UNIVERSITY OF BUCHAREST DEPARTMENT UNESCO CHAIR ON THE STUDY OF INTER-CULTURAL AND INTER-RELIGIOUS EXCHANGES MASTER „ COMMUNICATION AND INTERCULTURAL MANAGEMENT ” EARLY CHRISTIAN WOMEN WRITERS: THE INTERESTING LIVES AND WORKS OF FALTONIA BETITIA PROBA AND ATHENAIS-EUDOCIA Authors: Cătălina M ărmureanu Gianina Cernescu Laura Lixandru Scientific coordinator: Prof. univ. dr. Sylvie Hauser-Borel Bucharest 2008 Contents Early Christian Women Writers: Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia / 3 Faltonia Betitia Proba (c.320-370 AD) / 4 The Empress Eudocia /Athenais-Eudocia/Aelia Eudokia (c.400-460 AD) / 11 Conclusion / 17 Bibliography / 18 Note on the Writers / 19 2 Early Christian Women Writers: Faltonia Betitia Proba and Athenais-Eudocia In the past two decades scholarship regarding the participation of women in the formation of Christian religion has witnessed an almost complete revision. As women historians have entered the field in record numbers, new perspectives and questions have been brought to the forefront. At the same time, the continuous exploration for evidence of women’s presence in previously neglected texts, have resulted in exciting new findings. For example, up to recent years only a few names were synonymous with this topic: Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, his disciple and the first witness to the resurrection, as well as Mary and Martha, the sisters who offered him hospitality in Bethany. 1 Today, primary sources along with historiography, have unveiled that women, despite facing restrictive opportunities to exercise their intellectual and literal skills, have bequeathed the church with a respectable literary and intellectual legacy. Religion transgressed the rigid boundaries enshrined by sex roles, thus permitting women to take interest, study, and most importantly participate in Christian theology. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ EUDOCIA: THE MAKING OF A HOMERIC CHRISTIAN A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 by Brian Patrick Sowers B.A., University of Evansville, 2001 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Peter van Minnen ii ABSTRACT With over 3,400 lines of poetry and no single monograph dedicated to her literary productions, Aelia Eudocia is an understudied poet. This project, the first of its kind, explores Eudocia's three poems as a unified whole and demonstrates how they exemplify the literary and cultural concerns of the fifth century. Since her poems are each apparently unique, I approach them first in isolation and tease out their social background, literary dependencies, and possible interpretive strategies for them before painting a broader picture of Eudocia's literary contribution. The first of her surviving poems is a seventeen line epigraphic poem from the bath complex at Hammat Gader, which acclaims the bath's furnace for its service to the structure's clients but, at the same time, illustrates the religious competition that surrounded late antique healing cults, of which therapeutic springs were part. Next is the Homeric cento, which borrows and reorders lines from the Iliad and Odyssey to retell parts of the biblical narrative. -

Structures of Epic Poetry Structures of Epic Poetry Volume III: Continuity

Structures of Epic Poetry Structures of Epic Poetry Volume III: Continuity Edited by Christiane Reitz and Simone Finkmann ISBN 978-3-11-049200-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049259-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049167-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953831 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Eric Naujoks (Rostock), Dr. Jörn Kobes (Gutenberg) Cover image: Carrara Marble Quarries, © Wulf Liebau (†), Photograph: Courtesy of Irene Liebau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Christiane Reitz and Simone Finkmann The origin, tradition, and reinvention of epic structures – a short introduction | 1 Johannes Haubold Poetic form and narrative theme in early Greek and Akkadian epic | 7 Simon Zuenelli The transformation of the epic genre in Late Antiquity | 25 Berenice Verhelst Greek biblical epic: Nonnus’ Paraphrase and Eudocia’s Homerocentones | 53 Christoph Schubert Between imitation and transformation: the (un)conventional use of epic structures in the Latin biblical poetry of Late Antiquity | 79 Martin Bažil Epic forms and structures in late antique Vergilian centos | 135 Kristoffel Demoen and Berenice Verhelst The tradition of epic poetry in Byzantine literature | 175 Wim Verbaal Medieval epicity and the deconstruction of classical epic | 211 Christian