The Synoptic Scientific Image in Early Modern Europe*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Derham: Csillagteológia () Forrásközlés Történeti-Fi Lológiai Bevezetéssel Szénási Réka – Vassányi Miklós

William Derham: Csillagteológia () Forrásközlés történeti-fi lológiai bevezetéssel Szénási Réka – Vassányi Miklós 1. Derham és a fi ziko-teológia. William Derham (1657-1735) anglikán lelkész polihisztor, természettudós, a Royal Society tagja és a fi ziko-teológiai mozgalom jeles alakja volt. Az alábbi részletet egyik fő művéből, az Astro-Th eology-ból az- zal a céllal közöljük, hogy betekintést nyújtsunk a kora újkori natural theology – kozmikus vagy fi ziko-teológia – egyik nagy hatású angol műhelyébe, és ezáltal megmutassuk, hogy a korszak egy paradigmatikus fi gurája, a természettudós-lelki- pásztor (parson-naturalist) Derham hogyan egyeztette össze a vallást a természet- tudománnyal, illetve – pontosabban – hogyan állította a természetismeretet a hit, az apologetika és a térítés szolgálatába. A többkötetes, népszerű szerző nem volt ugyan hivatásos fi zikus vagy csillagász, de rendszeresen felolvasott a Royal Society ülésein, jó negyven hozzájárulással gazdagította annak folyóiratát, a Philosophical Transactionst, és voltak eredeti fi zikatudományi eredményei (hangsebesség méré- se), valamint technológiai munkássága is (óramechanika), tehát a kor mércéjével mérve természettudósnak is számított. Egész életére kiterjedő lelkészi működését végigkísérte a természettudomány több területének – orvostudomány, biológia, geológia, meteorológia, csillagászat – különösen megfi gyelő tudósként való mű- velése. A természettudomány és a vallás termékeny összekapcsolására mindenek- előtt a nevezetes Boyle Lectures (ld. alant) felkért előadójaként -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine Author(S): MARTHA R

Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine Author(s): MARTHA R. BALDWIN Source: Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Summer 1993), pp. 227-247 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44444207 Accessed: 02-07-2018 17:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the History of Medicine This content downloaded from 132.174.255.223 on Mon, 02 Jul 2018 17:14:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine MARTHA R. BALDWIN The seventeenth century witnessed a sharp interest in the medical applications of amulets. As external medicaments either worn around the neck or affixed to the wrists or armpits, amulets enjoyed a sur- prising vogue and respectability. Not only does this therapy appear to have been a fashionable folk remedy in the seventeenth century,1 but it also received acceptance and warm enthusiasm from learned men who strove to incorporate the curative and prophylactic benefits of amulets into their natural and medical philosophies. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 May 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Bi§cak,Ivana (2020) 'A guinea for a guinea pig : a manuscript satire on England's rst animalhuman blood transfusion.', Renaissance studies., 34 (2). pp. 173-190. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12571 Publisher's copyright statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Bi§cak,Ivana (2020). A guinea for a guinea pig: a manuscript satire on England's rst animalhuman blood transfusion. Renaissance Studies 34(2): 173-190 which has been published in nal form at https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12571. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk A Guinea for a Guinea Pig: A Manuscript Satire on England’s First Animal-Human Blood Transfusion1 Utilis est rubri, qvæ fit, transfusio succi, At metus est, homo ne candida fiat ovis. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 12:40:43AM Via Free Access 206 René Sigrist Plants

ON SOME SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BOTANISTS René Sigrist* In the eighteenth century, the systematic study of plants was already an old story that could be traced back to the Renaissance and even to clas- sical antiquity. Yet the existence of botany as a science independent of medicine was not as old. It would be difficult to ascertain to what extent it was already a discipline practised by specialized scholars—not to men- tion professionals.1 In 1751 Linné, in his Philosophia botanica, had tried to define the aims and the ideal organisation of such a discipline. Yet, despite the many students who came to hear him in Uppsala, and his eminent position within the Republic of Letters, it was not in his power to impose professional standards on other botanists. Diverging concep- tions of the science of plants persisted at least until the final triumph of Jussieu’s natural method of classification, in the early nineteenth century. The emergence of the professional botanist would be a still longer pro- cess, with important differences from one country to another. The pres- ent article aims to analyse the social status of botanists in the eighteenth century and in the early nineteenth century, a period which can be char- acterised as the golden age of scientific academies.2 Starting with Linné’s conception of the division of tasks within the community of phytologues, it focuses on the social perception of botanists, on the structure of episto- lary links within the Republic of Botanists, and finally on the professional activities and social origins of the major contributors to the science of * Invited scholar (FWO Fellow) at Gent University, Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences. -

English Mechanical Philosophy and Newton (1642-1727)

Ann Blair, CB-20 Lecture 14: English mechanical philosophy and Newton (1642-1727) I. English reaction to Descartes: mech phil with God put back in • Defending nat phil against accusations of arrogance, of deism; nat phil as argument ag. atheists; mechanical philosophy as Christian, more pious than Aristotle • Royal Society founded 1662. Robert Hooke, Micrographia (1665): vocabulary of awe and wonder at the contrivance of even the smallest creatures (gnat)= natural theology (John Ray, William Derham, Boyle lectures. incl Richard Bentley as 1st lecturer) II. Newton’s physics: Awe and wonder at the laws of the universe: “Behold the regions of the heavens surveyed,/ and this fair system in the balance weighed! Behold the law which (when in ruin hurled/ God out of chaos called the beauteous world) th'Almighty fixed when all things good he saw!/ Behold the chaste, inviolable law!” (prefixed to the Principia) Principia (1687)[“mathematical principles of natural philosophy]: bk 1. 3 laws of motion (inertia, F=ma; action and reaction); bk 2: derives Kepler’s 2nd and 3rd laws; bk 3: gravitational force as inverse square law (explains elliptical orbits) • 1713 2nd ed with General scholium (=additional remark): re gravitation: “hypotheses non fingo” (inscrutability of the world) + God’s dominion in the world (space and time) • Opticks (1722): more speculative. “subtle fluid”=ether III. Newton on theology: • Letters to Bentley (for Boyle lectures): gravity not a property of matter (avoid materialism); need supernatural deity to explain distribution of matter + periodic acts of reformation by God (e.g. comets) • theological mss (private): Arianism (because Biblical text supporting Trinity is corrupt); but accepts Bible as divine message: history as fulfillment of biblical prophecies • alchemy: study cohesion of matter explained by subtle spirit (=div prov) IV. -

Science and Religion: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives Course

Science and Religion: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives Course: History of Science and Technology 3030 Institution: University of King’s College, Halifax Instructor: Professor Stephen D. Snobelen “Religion and science are opposed . but only in the same sense as that in which my thumb and forefinger are opposed — and between the two, one can grasp everything.” ---Sir William Bragg (1862-1942), Pioneer in X-Ray crystallography Summary of course aims: -- to trace and examine the relationships between religion and science through history as religion and science have themselves developed over the millennia -- to determine and examine the relationships between religion and science in the postmodern world today -- to identify and examine converges between religion and science in the past and today -- to stimulate the development of a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of Science- Religion issues on the part of Arts, Journalism and Science undergraduates -- to help promote dialogue between the sciences and humanities at King’s and Dalhousie -- to provide a flagship course for the King’s History of Science and Technology programme, founded in 2000 Course legacies: -- this course will be offered yearly and will become a permanent and prominent part of the King’s HOST and Dalhousie Science curricula -- a course website will be created that will continue to grow in as the course continues to develop -- the course is also intended to serve as the springboard for the creation of an interdisciplinary Society for Science-Religion Dialogue -

Mankind a Masterpiece of God’S Creation

Mankind a Masterpiece of God’s creation Dr Isabel Moraes …The human body is a self-building machine, a self-stoking, self-regulating, self-repairing machine…. ….the most marvellous and unique automatic mechanism in the universe (our universe) Dr Isabel Moraes …we are able to create other beings like us.... Dr Isabel Moraes …three weeks from the conception the baby heart start beating…. ….during this week the baby blood vessels will complete the circuit and the circulation begins – making the circulatory system the first functioning organ system… …At this week the baby the size of a tip of a pen… Dr Isabel Moraes …Its colour-analysis system enables the eye to distinguish millions of shades of colour and quickly adjust to lighting conditions (incandescent, fluorescent, underwater or sunlight) that would require a photographer to change filters, films thousand times in a second… …Whereas each human fingerprint has 35 measurable characteristics, each iris has 266. The chance of two people will have matching iris is one in 1078 …Passing through the lens, the light is further focused, a fine-tuning. Then it strikes the pigmented retina. The retina has 127 million photovoltaic receptors. The information of these 127 million receptors is converted from light to electricity and transmitted along one million nerves fibers to the 1% of the cortex of the brain... Dr Isabel Moraes The retina never stops “shooting” pictures, and each fibre of the optical nerve processes 100 “photos” each second… …Each of these “photos” can be represented mathematically by 50,000 nonlinear differential equations. All these equations are solved by our brain (cortex) every 1/100 of second… Summit or OLCF-4 A supercomputer would require years to process the information that your eye transmits every 1/100 of second. -

Rev. Cotton Mather, the Christian Philosopher, 1721, Excerpts

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763 Rev. COTTON MATHER New York Public Library The Christian Philosopher A Collection of the Best Discoveries in Nature, with Religious Improvements 1721, EXCERPTS * Cotton Mather, the Puritan clergyman who published hundreds of sermons and theological works, also produced the first American compilation of scientific knowledge, The Christian Philosopher. (The term “natural philosophy” referred to the pursuit of scientific knowledge; thus the “Christian philosopher” studied scientific knowledge within the perspective of Christian theology.) For Mather, science was an “incentive to Religion” that fostered reverence and moral insight. “Theologians had long studied nature in order to understand the will of God,” asserts historian Winton Solbert. “Now they and their allies welcomed scientific advances that explained how God’s Providence advanced divine purposes in the physical universe. Mather always saw harmony rather than conflict between science and religion.”1 Presented here is a representative sampling of Mather’s review of scientific knowledge—the “Works of the glorious God exhibited to our View.” The brief excerpts from each chapter reveal Mather’s respect for scientific inquiry and his spiritual devotion in response to the natural world. THE INTRODUCTION_____ The ESSAYS now before us will demonstrate that Philosophy [science] is no Enemy, but a mighty and wondrous Incentive to Religion; and they will exhibit that PHILOSOPHICAL RELIGION, which will carry with it a most sensible Character and victorious Evidence of a reasonable Service. GLORY TO GOD IN THE HIGHEST, and GOOD WILL TOWARDS MEN, animated and exercised; and a Spirit of Devotion and of Charity inflamed, in such Methods as are offered in these Essays, cannot but be attended with more Benefits, than any Pen of ours can declare or any Mind conceive. -

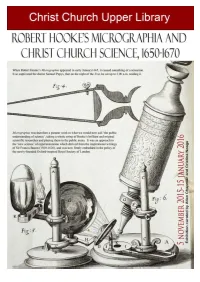

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

Downloaded 10/10/21 09:06 PM UTC Bulletin American Meteorological Society 1059

John F. Griffiths A Chronology ol llems of Department of Meteorology Texas A8cM University Meteorological interest College Station, Tex. 77843 Any attempt to select important events in meteorology The importance of some events was not really recog- must be a personal choice. I have tried to be objective nized until years later (note the correspondence by and, additionally, have had input from some of my Haurwitz in the August 1966 BULLETIN, p. 659, concern- colleagues in the Department of Meteorology. Neverthe- ing Coriolis's contribution) and therefore, strictly, did less, I am likely to have omissions from the list, and I not contribute to the development of meteorology. No would welcome any suggestions (and corrections) from weather phenomena, such as the dates of extreme hurri- interested readers. Naturally, there were many sources canes, tornadoes, or droughts, have been included in this of reference, too many to list, but the METEOROLOGICAL present listing. Fewer individuals are given in the more AND GEOASTROPHYSICAL ABSTRACTS, Sir Napier Shaw's recent years for it is easier to identify milestones of a Handbook of Meteorology (vol. 1), "Meteorologische science when many years have passed. 1 Geschichstabellen" by C. Kassner, and One Hundred i Linke, F. (Ed.), 1951: Meteorologisches Taschenbuch, vol. Years of International Co-operation in Meteorology I, 2nd ed., Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Geest & Portig, (1873-1973) (WMO No. 345) were most useful. Leipzig, pp. 330-359. (1st ed., 1931.) B.C. 1066 CHOU dynasty was founded in China, during which official records were kept that in- cluded climatic descriptions. #600 THALES attributed the yearly Nile River floods to wind changes. -

Catholicism and Science

Catholicism and Science PETER M. J. HESS AND PAUL L. ALLEN Greenwood Guides to Science and Religion Richard Olson, Series Editor Greenwood Press r Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Peter M. J. Catholicism and science / Peter M. J. Hess and Paul L. Allen. p. cm. — (Greenwood guides to science and religion) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–313–33190–9 (alk. paper) 1. Religion and science—History. 2. Catholic Church—Doctrines—History. I. Allen, Paul L. II. Title. BX1795.S35H47 2008 261.5 5088282—dc22 2007039200 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2008 by Peter M. J. Hess and Paul L. Allen All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007039200 ISBN: 978–0–313–33190–9 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xvii Acknowledgments xix Chronology of Events xxi Chapter 1. Introduction to Science in the Catholic Tradition 1 Introduction: “Catholicism” and “Science” 1 The Heritage of the Early Church 3 Natural Knowledge in the Patristic Era 6 Science in the Early Middle Ages: Preserving Fragments 12 The High Middle Ages: The Rediscovery of Aristotle and Scholastic Natural Philosophy 15 Later Scholasticism: Exploring New Avenues 21 Conclusion: From Late Scholasticism into Early Modernity 23 Chapter 2.