Catholicism and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

CIA Controversy Continues

-- THE MONDAY NOV l:-- .L ' . John Kissel 1 j VOL. IV, No. 49 Serving the Notre Darrle aniSaint Mary's College Community MONDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1969 l Dow CIA controversy continues oy Rich Smith - Corporation and the Central tests "depends on how the Dedrick was told that the leal Plans for a rally today at 2:30 lass, spokesman for the group. In te IIi gence Agency. .the administration responds to the lets had been confiscated were finalized at a meeting yes Those aims were enunciated impropriety of allowin3 organi original issue," Douglass said. because he had not been given terday afternoon by the people in the faculty statement issued zations engaged in the sale and At the conclusion of the permission to distribute them. involved in the L>ow-CIA protest on November 19, and include: export of death and repression meeting, Tim MacCarry, who When he attempted to leave of last week. A dcdsion on any "Tbe university's subservience to to recruit Notre Dame students was arrested for loitenng on with the leaflets, Dedrick said further adion to be taken will the political and economic sys with complete cooperation of Tuesday, commented on what is that the police officer grabbed he made after the hearing on tem represented by the Dow the University, .. .forcing under involved in the dispute. "It is his arm and the leaflets. Dedrick Wednesday wncerning the ex graduates, graduates, and faculty impo.rtant to keep in mind that accused the officer of robbing pulsion of five students and the members into direct action to the main issue here is University him of his leaflets. -

Champ Math Study Guide Indesign

Champions of Mathematics — Study Guide — Questions and Activities Page 1 Copyright © 2001 by Master Books, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced for educational purposes only. BY JOHN HUDSON TINER To get the most out of this book, the following is recommended: Each chapter has questions, discussion ideas, research topics, and suggestions for further reading to improve students’ reading, writing, and thinking skills. The study guide shows the relationship of events in Champions of Mathematics to other fields of learning. The book becomes a springboard for exploration in other fields. Students who enjoy literature, history, art, or other subjects will find interesting activities in their fields of interest. Parents will find that the questions and activities enhance their investments in the Champion books because children of different age levels can use them. The questions with answers are designed for younger readers. Questions are objective and depend solely on the text of the book itself. The questions are arranged in the same order as the content of each chapter. A student can enjoy the book and quickly check his or her understanding and comprehension by the challenge of answering the questions. The activities are designed to serve as supplemental material for older students. The activities require greater knowledge and research skills. An older student (or the same student three or four years later) can read the book and do the activities in depth. CHAPTER 1 QUESTIONS 1. A B C D — Pythagoras was born on an island in the (A. Aegean Sea B. Atlantic Ocean C. Caribbean Sea D. -

William Derham: Csillagteológia () Forrásközlés Történeti-Fi Lológiai Bevezetéssel Szénási Réka – Vassányi Miklós

William Derham: Csillagteológia () Forrásközlés történeti-fi lológiai bevezetéssel Szénási Réka – Vassányi Miklós 1. Derham és a fi ziko-teológia. William Derham (1657-1735) anglikán lelkész polihisztor, természettudós, a Royal Society tagja és a fi ziko-teológiai mozgalom jeles alakja volt. Az alábbi részletet egyik fő művéből, az Astro-Th eology-ból az- zal a céllal közöljük, hogy betekintést nyújtsunk a kora újkori natural theology – kozmikus vagy fi ziko-teológia – egyik nagy hatású angol műhelyébe, és ezáltal megmutassuk, hogy a korszak egy paradigmatikus fi gurája, a természettudós-lelki- pásztor (parson-naturalist) Derham hogyan egyeztette össze a vallást a természet- tudománnyal, illetve – pontosabban – hogyan állította a természetismeretet a hit, az apologetika és a térítés szolgálatába. A többkötetes, népszerű szerző nem volt ugyan hivatásos fi zikus vagy csillagász, de rendszeresen felolvasott a Royal Society ülésein, jó negyven hozzájárulással gazdagította annak folyóiratát, a Philosophical Transactionst, és voltak eredeti fi zikatudományi eredményei (hangsebesség méré- se), valamint technológiai munkássága is (óramechanika), tehát a kor mércéjével mérve természettudósnak is számított. Egész életére kiterjedő lelkészi működését végigkísérte a természettudomány több területének – orvostudomány, biológia, geológia, meteorológia, csillagászat – különösen megfi gyelő tudósként való mű- velése. A természettudomány és a vallás termékeny összekapcsolására mindenek- előtt a nevezetes Boyle Lectures (ld. alant) felkért előadójaként -

The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East

Open Theology 2017; 3: 565–589 Analytic Perspectives on Method and Authority in Theology Nathan A. Jacobs* The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2017-0043 Received August 11, 2017; accepted September 11, 2017 Abstract: The questions of whether God reveals himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. W. Leibniz, and Immanuel Kant, to name a few. Yet, what these philosophers say with such consistency about revelation stands in stark contrast with the claims of the Christian East, which are equally consistent from the second century through the fourteenth century. In this essay, I will compare the modern discussion of special revelation from Thomas Hobbes through Johann Fichte with the Eastern Christian discussion from Irenaeus through Gregory Palamas. As we will see, there are noteworthy differences between the two trajectories, differences I will suggest merit careful consideration from philosophers of religion. Keywords: Religious Epistemology; Revelation; Divine Vision; Theosis; Eastern Orthodox; Locke; Hobbes; Lessing; Kant; Fichte; Irenaeus; Cappadocians; Cyril of Alexandria; Gregory Palamas The idea that God speaks to humanity, revealing things hidden or making his will known, comes under careful scrutiny in modern philosophy. The questions of whether God does reveal himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. -

James Hutton, the Scottish Enlightenment and the North West

by Vivien As old as the hills Martin ECENTLY we had a display of fossils Rin the library. A young woman with two small children examined a fossilised James Hutton, the Scottish dinosaur tooth with great interest. She then turned to me and asked if cavemen would have kept dinosaurs as pets. And to my surprise the question was serious. Enlightenment and the It brought home to me just how difficult the concept of time can be. Especially the further back you go. All those billions of years that have gone into creating North West Highlands Geopark the planet we know today, including the millions it’s taken for our particular bit of it, Scotland, to reach its present form. Such a vast span of time can be hard, if not impossible, for our minds to grasp. This ‘deep time’, as it’s called, is measured in eons, eras, periods and epochs. Geologists believe that many of these eras were brought to an end by specific cataclysmic events. Like, for example, the one 64 million years ago, when a gigantic meteor strike is thought to have set off a chain reaction so destructive that it led to mass extinctions on Earth, the dinosaurs included. Extinctions that occurred long, long before the arrival of humans. So no, if you were a caveman you most certainly wouldn’t have had a dinosaur as a pet! Fred Flintstone has a lot to answer for! “Go to the mountains to read the immeasurable course of time.” James Hutton, 1788 Fred Flintstone has a lot to Fred & Dino Credit Hanna-Barbera Gruinard Bay answer for! Prof Lorna The North West Highlands Dawson of the Geopark welcomes you! James Hutton Institute So how do we know how old the earth is? After all, humankind is one of the more recent additions to the planet and people weren’t around to witness what happened. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

Amphibiaweb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth

AmphibiaWeb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth Created and Illustrated by the 2020-2021 AmphibiaWeb URAP Team: Alice Drozd, Arjun Mehta, Ash Reining, Kira Wiesinger, and Ann T. Chang This introduction to amphibians was written by University of California, Berkeley AmphibiaWeb Undergraduate Research Apprentices for people who love amphibians. Thank you to the many AmphibiaWeb apprentices over the last 21 years for their efforts. Edited by members of the AmphibiaWeb Steering Committee CC BY-NC-SA 2 Dedicated in loving memory of David B. Wake Founding Director of AmphibiaWeb (8 June 1936 - 29 April 2021) Dave Wake was a dedicated amphibian biologist who mentored and educated countless people. With the launch of AmphibiaWeb in 2000, Dave sought to bring the conservation science and basic fact-based biology of all amphibians to a single place where everyone could access the information freely. Until his last day, David remained a tirelessly dedicated scientist and ally of the amphibians of the world. 3 Table of Contents What are Amphibians? Their Characteristics ...................................................................................... 7 Orders of Amphibians.................................................................................... 7 Where are Amphibians? Where are Amphibians? ............................................................................... 9 What are Bioregions? ..................................................................................10 Conservation of Amphibians Why Save Amphibians? ............................................................................. -

Messages from Salzburg

Messages from Salzburg SEH 19th European Congress of Herpetology Dr Tony Gent SEHCC Chair Trondheim October 2017 RACE Foundation Conservation Committee SEH Congress & OGM • University of Salzburg, Department of Ecology and Evolution • The Congress ran from: Monday 18th September to Friday 22nd September • Two parallel sessions, plus plenary lectures each day (book of Abstracts available) • Session on diseases (Thursday) • Practical conservation session (Friday) • SEHCC meeting (Tuesday) • OGM saw new Council members including new president (Mathieu Denoël) • I identify some key messages/ topics from the conference that have a bearing on conservation • Issues around pathogens/ disease, eg. Bsal, not included as dealt with elsewhere Genetics & phylogeography Splitting & merging of taxa giving increasingly fluid taxonomic positons & status: do we need to develop new guidelines to keep up with changes: Proteus anguinus - now perhaps up to 8-10 species recognised Olm Proteus anguinus in very restricted geographic area: Italy- Montenegro http://www.animalspot.net/wp- Vipera darevski & V. eriwanensis probably just a single species : content/uploads/2012/01/Olm-Photos.jpg upgrades status as now occupy larger range. Importance of different ‘forms’ e.g. paedomorphic newt populations Phylogeography helps identify geographic areas of particular significance from an evolutionary point of view; e.g. Carpathean Basin. Does this warrant increased conservation interest/ effort to protect these area? Darevsky’s viper Vipera darevskii http://www.arkive.org/darevskys-viper/vipera- -

Creation and God As One, Creator, and Trinity in Early Theology Through Augustine and Its Theological Fruitfulness in the 21St Century

Creation and God as One, Creator, and Trinity in Early Theology through Augustine and Its Theological Fruitfulness in the 21st Century Submitted by Jane Ellingwood to the University of Exeter as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology in September 2015 This dissertation is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the dissertation may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this dissertation which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: _________Jane Ellingwood _________________________ 2 Abstract My primary argument in this thesis is that creation theologies significantly influenced early developments in the doctrine of the Trinity, especially in Augustine of Hippo’s theology. Thus this is a work of historical theology, but I conclude with proposals for how Augustine’s theologies of creation and the Trinity can be read fruitfully with modern theology. I critically analyse developments in trinitarian theologies in light of ideas that were held about creation. These include the doctrine of creation ‘out of nothing’ and ideas about other creative acts (e.g., forming or fashioning things). Irenaeus and other early theologians posited roles for God (the Father), the Word / Son, the Spirit, or Wisdom in creative acts without working out formal views on economic trinitarian acts. During the fourth century trinitarian controversies, creation ‘out of nothing’ and ideas about ‘modes of origin’ influenced thinking on consubstantiality and relations within the Trinity. -

Olm, Proteus Anguinus

Olm, Proteus anguinus Compiler: Jelić, D. Contributors: Jelić, D.; Jalžić, B.; Kletečki, E.; Koller, K.; Jalžić, V.; Kovač-Konrad, P. Suggested citation: Jelić, D. (2014): A survival blueprint for the olm, Proteus anguinus. Croatian Institute for Biodiversity, Croatian Herpetological Society, Zagreb, Croatia. 1. STATUS REVIEW 1.1 Taxonomy: Chordata > Amphibia > Caudata > Proteidae > Proteus > anguinus Most populations are assigned to the subterranean subspecies Proteus anguinus anguinus. Unlike the nominate form, the genetically similar subspecies P.a. parkelj from Bela Krajina in Slovenia is pigmented and might represent a distinct species, although a recent genetic study suggests that the two subspecies are poorly differentiated at the molecular level and may not even warrant subspecies status (Goricki and Trontelj 2006). Isolated populations from Istria peninsula in Croatia are genetically and morphologically differentiated as separate unnamed taxon (Goricki and Trontelj 2006). Croatian: Čovječja ribica English: Olm, Proteus, Cave salamander French: Protee Slovenian: Čovješka ribica, močeril German: Grottenolm 1.2 Distribution and population status: 1.2.1 Global distribution: Country Population Distribution Population trend Notes estimate (plus references) (plus references) Croatia 68 localities (Jelić 3 separate Decline has been et al. 2012) subpopulations: observed through Istria, Gorski devastation of kotar and several cave Dalmatia systems in all regions (Jelić et al. 2012) Italy 29 localities (Sket Just the A decline has been 1997) easternmost observed in the region around population of Trieste, Gradisce Goriza (Italy) (Gasc and Monfalcone et al. 1997). Slovenia 158 localities 4 populations A decline has been (Sket 1997) distributed from observed in the Vipava river in the population in west (border with Postojna (Slovenia) Italy) to Kupa (Gasc et al. -

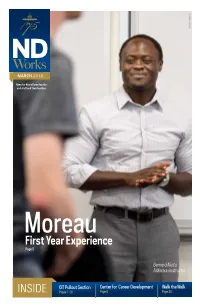

First Year Experience Page 5

NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME BARBARA JOHNSTON NDND MARCH 2018 News for Notre Dame faculty and staff and their families Moreau First Year Experience Page 5 Bernard Akatu A Moreau instructor OIT Pullout Section Center for Career Development Walk the Walk INSIDE Pages 7-10 Page 6 Page 16 2 | NDWorks | March 2018 NEWS MATT CASHORE MATT MATT CASHORE MATT PHOTO PROVIDED BARBARA JOHNSTON BRIEFS BARBARA JOHNSTON WHAT’S GOING ON ICEALERT SIGN INSTALLED BY Nucciarone Corcoran Seabaugh Haenggi Kamat STAIRS IN GRACE/VISITOR LOT A color-changing IceAlert sign, intended to make pedestrians aware areas of the University, including innovation in creating or facilitating pastoral leadership development of of icy or slick conditions on the Notre Dame Research, the IDEA outstanding inventions that have CAMPUS NEWS lay ministers early in their careers. stairs, walkway or parking lot, has Center, University Relations and made a tangible impact on quality of been installed along the staircase to the Office of Public Affairs and Com- life, economic development and wel- BREITMAN AND BREITMAN- NANOVIC INSTITUTE AWARDS the Grace Hall/Visitor parking lot munications, to positively affect both fare of society.” JAKOV NAMED 2018 DRIEHAUS LAURA SHANNON PRIZE TO south of Stepan Center. The color on the South Bend-Elkhart region and PRIZE LAUREATES ‘THE WORK OF THE DEAD’ the University. the sign transitions from gray to blue CORCORAN APPOINTED Marc Breitman and Nada The Nanovic Institute for Euro- whenever temperatures dip below EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF Breitman-Jakov, Paris-based architects pean Studies has awarded the 2018 freezing. NUCCIARONE TO SERVE ON THE KROC INSTITUTE known for improving cities through Laura Shannon Prize in Contempo- HIGHER EDUCATION Erin B.