Queensland: Renewable One Day, and the Next, and Next…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Downs Development Status Report

Toowoomba and Surat Basin Enterprise Western Downs Development Status Report June 2020 www.tsbe.com.au WESTERN DOWNS DEVELOPMENT STATUS REPORT The Western Downs, located in the agricultural heartland of Southern Queensland, is a region experiencing strong economic growth, investment and consistently high employment. The region is well known for its rich agriculture and great liveability, but its biggest wealth is in its people and communities. Home to a growing population of 34,500 people, the Western Downs is a region known for welcoming industry and innovation as well as extending its country hospitality to all new residents and businesses. The Western Downs Development Status Report is a document produced in partnership with Western Downs Regional Council and is updated annually. It equips readers with knowledge including costs, locations and estimated completion dates for known developments in the Western Downs region across infrastructure and services, property development, building and construction, resources and renewable energy projects. Toowoomba and Surat Basin Enterprise (TSBE) is committed to fostering and facilitating the sustainable growth and development of the region and works with stakeholders across the Western Downs to support the local business community. TSBE supports regional businesses through the delivery of information, business support programs, advocacy and regional promotion, as well as membership services to many local businesses. The cornerstones of the economy are agriculture, intensive agriculture, energy and manufacturing — industries which continue to boast a significant number of projects in the pipeline for the Western Downs area. TSBE and Western Downs Regional Council hope this report will encourage further investment in the region, while also providing businesses with important information to help them explore new opportunities. -

Diamantina and Leichhardt Power Stations

Diamantina and Leichhardt Power Stations 29 March 2016 Disclaimer This presentation has been prepared by Australian Pipeline Limited (ACN 091 344 704) the responsible entity of the Australian Pipeline Trust (ARSN 091 678 778) and APT Investment Trust (ARSN 115 585 441) (APA Group). Summary information: This presentation contains summary information about APA Group and its activities current as at the date of this presentation. The information in this presentation is of a general background nature and does not purport to be complete nor does it contain all the information which a prospective investor may require in evaluating a possible investment in APA Group. It should be read in conjunction with the APA Group’s other periodic and continuous disclosure announcements which are available at www.apa.com.au. Not financial product advice: Please note that Australian Pipeline Limited is not licensed to provide financial product advice in relation to securities in the APA Group. This presentation is for information purposes only and is not financial product or investment advice or a recommendation to acquire APA Group securities and has been prepared without taking into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of individuals. Before making an investment decision, prospective investors should consider the appropriateness of the information having regard to their own objectives, financial situation and needs and consult an investment adviser if necessary. Past performance: Past performance information given in this presentation is given for illustrative purposes only and should not be relied upon as (and is not) an indication of future performance. Future performance: This presentation contains certain “forward-looking statements” such as indications of, and guidance on, future earnings and financial position and performance. -

Renewable Energy Across Queensland's Regions

Renewable Energy across Queensland’s Regions July 2018 Enlightening environmental markets Green Energy Markets Pty Ltd ABN 92 127 062 864 2 Domville Avenue Hawthorn VIC 3122 Australia T +61 3 9805 0777 F +61 3 9815 1066 [email protected] greenmarkets.com.au Part of the Green Energy Group Green Energy Markets 1 Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................6 2 Overview of Renewable Energy across Queensland .....................................................8 2.1 Large-scale projects ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Rooftop solar photovoltaics ........................................................................................................ 13 2.3 Batteries-Energy Storage ........................................................................................................... 16 2.4 The renewable energy resource ................................................................................................. 18 2.5 Transmission .............................................................................................................................. 26 3 The renewable energy supply chain ............................................................................. 31 3.1 Construction activity .................................................................................................................... 31 3.2 Equipment manufacture -

FCAS Causer Pays Settlement Factors

FCAS Causer Pays Settlement Factors Issued: 30/04/2021 Period of Application: 16/05/2021 to 12/06/2021 Sample Period: 12:05AM, 28/03/2021 to 12:00AM, 25/04/2021 Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania Region Causer Pays Factors Scheduled and Semi-Scheduled Aggregations Factor AETV Pty Ltd 0.05961137 AGL Hydro Partnership 3.539372198 AGL Loy Yang Marketing Pty Ltd 0 AGL Macquarie Pty Limited 0 AGL PARF NSW Pty Ltd 0.208683361 AGL PARF QLD Pty Limited 1.425163283 AGL SA Generation Pty Limited 0 Alinta Energy Retail Sales Pty Ltd 0 Ararat Wind Farm Pty Ltd 0.654666275 Arrow Southern Generation Pty Ltd And Arrow Braemar 2 Pty Ltd 0 Berrybank Development Pty Ltd 0.622023582 Boco Rock Wind Farm Pty Ltd 0.130189533 Bodangora Wind Farm Pty Limited 0.164570436 Bomen Solar Farm Pty Ltd As Trustee For Bomen SF Trust 0.801625587 Braemar Power Project Pty Ltd 0.237625656 Bulgana Wind Farm Pty Ltd 0.296692747 BWF Nominees Pty Ltd As The Trustee For BWF Trust 0 Callide Power Trading Pty Limited 0 Capricorn SF No1 Pty Ltd 0.074125563 Cherry Tree Wind Farm Pty Ltd As Trustee For The Cherry Tree Project Trust 0 Childers Solar Pty Ltd ATF The Childers Solar Trust 0 Clare Solar Farm Pty Ltd 0.07813942 CleanCo Queensland Limited 1.102955143 Clermont Asset Co Pty Ltd ATF Clermont Solar Unit Trust 0 Coleambally Solar Pty Ltd 0.971950966 Collector Wind Farm Pty Ltd 0.784531539 Corowa Operationsco Pty Ltd As The Trustee For Corowa Operations Trust 0.007038657 Crookwell Development Pty Ltd 0.041882193 CRWF Nominees Pty Ltd As Trustee -

Powerlink Queensland Revenue Proposal

2023-27 POWERLINK QUEENSLAND REVENUE PROPOSAL Appendix 5.02 – PUBLIC 2020 Transmission Annual Planning Report © Copyright Powerlink Queensland 2021 Transmission Annual Planning Report 2020 Transmission Annual Planning Report Please direct Transmission Annual Planning Report (TAPR) enquiries to: Stewart Bell A/Executive General Manager Strategy and Business Development Division Powerlink Queensland Telephone: (07) 3860 2801 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: While care is taken in the preparation of the information in this report, and it is provided in good faith, Powerlink Queensland accepts no responsibility or liability for any loss or damage that may be incurred by persons acting in reliance on this information or assumptions drawn from it. 2020 TRANSMISSION ANNUAL PLANNING REPORT Table of contents Executive summary __________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 1. Introduction ________________________________________________________________________________________________ 15 1.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________________________ 16 1.2 Context of the TAPR _________________________________________________________________________________ 16 1.3 Purpose of the TAPR _________________________________________________________________________________ 17 1.4 Role of Powerlink Queensland _______________________________________________________________________ 17 1.5 Meeting the challenges of a transitioning energy system ___________________________________________ -

Renewable Energy in the Western Downs

‘Renewable Energy is an integral part of the Western Downs future economy creating short- and long- Renewable Energy in the term employment Western Downs opportunities for our The Western Downs is known as the RENEWABLE ENERGY region.’ Energy Capital of Queensland, and is INDUSTRY: now emerging as the Energy Capital of According to the Clean Energy Australia - Paul McVeigh, Australia. Report, as at 2018, Queensland Mayor Western Downs This reputation is due to strong renewables make up 9.5% of Renewable investment over the past 15 years Energy Penetration across Australian Regional Council 4 by the Energy Production Industry states. (EPI), into large-scale resource As at January 2019, the Western Electricity transmission services industry developments in coal seam Downs contributes towards this provider, Powerlink Queensland, gas (CSG) and coal. More recently percentage with more than $4 billion connects renewable energy farms renewable energy farms have invested in renewable energy projects in the across the region into the Queensland in the region with multiple solar and pipeline. 5 transmission network using existing, wind energy farms currently either Renewable energy projects offer and where required, expanding on under construction, or approved for short and long-term work within the transmission networks and substations. construction. Gas and coal-fired power region, with a range of industries and This existing infrastructure supports stations also feature prominently in the businesses involved. This creates a the connection of non-synchronous region. strong flow-on effect in the supply generation of electricity into the chain, economy and local communities. Economic growth in the Western Queensland transmission network. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

Level 6, 28 O’Connell Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 4626, Sydney NSW 2001 t. + 61 2 9048 8850 e. [email protected] w. www.genexpower.com.au 5 June 2017 ASX Announcement GENEX WELCOMES QLD STATE GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCEMENT OF STRATEGIC TRANSMISSION INFRASTRUCTURE FOR NORTH QUEENSLAND Genex Power Limited (ASX: GNX) (Genex or Company) welcomes the announcement from the Hon. Annastacia Palasczcuk, Queensland State Premier, in relation to the development of transmission infrastructure in North Queensland to unlock up to 2000MW of renewable projects in the region. As part of the announcement, the Queensland Government has stated that it will commit $150m towards developing a transmission line which will allow the 250MW Kidston Pumped Storage Hydro Project and the 270MW Kidston Solar Project (Stage Two) to connect directly into the national grid. This is a significant milestone for Genex as it secures a route to market for the renewable energy generated at Kidston. Genex will work with the government to ensure the development of the transmission assets fits in with the overall development of the Kidston Energy Hub. The media release states in part: “…The clean energy hub would connect the 75MW wind farm at Forsayth being developed by Infigen, the 520MW Kidston Hydro and Solar projects being developed by Genex and the Kennedy Energy Park, a combination of wind and solar generation with a capacity of 1200MW near Hughenden or other projects in the area.” Responding to the media release, Genex’s Executive Director Simon Kidston, who was present at the announcement by the Premier said: “The announcement of the feasibility study represents a very significant milestone for Genex. -

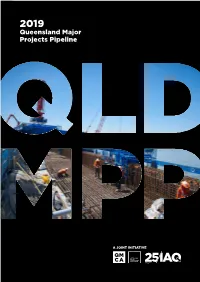

Queensland Major Projects Pipeline 2019 Queensland Major Projects Pipeline

2019 Queensland Major Projects Pipeline 2019 2019 Queensland Major Projects Pipeline Queensland Major Projects A JOINT INITIATIVE $M Total Pipeline 39,800,000,000 Annual Ave 7,960,000,000 Weekly Ave 153,000,000 Daily Ave 21,860,000 Hourly Ave 910,833 AT A GLANCE Major Projects Pipeline readon Unfunded split $41.3 billion total (over 5 years) Credibly Under Under Unlikely Prospective proposed Announced procurement construction* 37 39 15 36 15 52 projects valued at projects valued at projects valued at projects valued at projects valued at projects valued at $3.13bn $6.61bn $4.03bn $10.14bn $6.66bn $10.77bn Unfunded $13.77 billion Funded $27.57 billion *Under construction or completed in 2018/19 Total Pipeline Major Project Scale of Major Value Activity Recurring Projects Jobs Expenditure $8.3b per year The funded pipeline will support $6.5b 11,900 workers $41.3b North Queensland each year on average $23m per day $12.4b Fully-funding the pipeline Funding will support an extra 6.8b Central split Various Queensland 5,000 workers each year on average $23.4b $15.6b $2.2m Public Projects $41.3b Total South East A JOINT INITIATIVE $17.9b Queensland $159m per Private Projects working per week hour $M Total Pipeline 39,800,000,000 Annual Ave 7,960,000,000 Weekly Ave 153,000,000 Daily Ave 21,860,000 Hourly Ave 910,833 Major Projects Pipeline – Breakdown Unfunded split $41.3 billion total (over 5 years) Credibly Under Under Unlikely Prospective proposed Announced procurement construction* 37 39 15 36 15 52 projects valued at projects valued at projects -

Collgar Wind Farm Refinanced

Project Update Week ending 23 November 2018 Australia’s largest integrated battery with a solar farm ready for summer 16 November - The 25MW / 50MWh Gannawarra Energy National Electricity Market (NEM). GESS is Storage System (GESS) has completed capable of powering more than 16,000 homes construction and began exporting electricity through two hours of peak demand before to the grid on 16 October 2018 in time for being recharged. summer. - The project is among the largest integrated This is the first time a utility-scale battery solar and battery facilities in the world (the system has been retrofitted to an existing largest in Australia) providing capacity to use solar project, the Gannawarra Solar Farm, solar energy at night. providing a new commercial model for other - Financing for the GESS was underpinned by renewable and storage facilities in Australia. $25 million of grant funding from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) Australian renewable energy company Edify and the Victorian Government. Energy oversaw the deployment and - The project features a long-term commercial construction of the project, which utilises services agreement with EnergyAustralia, Tesla’s lithium ion battery technology. operator of the battery in conjunction with the offtake of the 60MW DC Gannawarra Energy retailer EnergyAustralia will charge Solar Farm. This is an innovative model for and dispatch energy from the facility until incorporating batteries into retail and 2030. This is in addition to a long-term corporate offtake arrangements. agreement to buy all the electricity generated from the co-located Gannawarra Solar Farm. Victoria’s Gannawarra Energy Storage System (GESS), the largest integrated solar and EnergyAustralia will operate the combined battery storage facility in Australia, is now solar farm and battery facility in a coordinated exporting and importing electricity to the grid way that better serves the Victorian energy and is ready to support the national energy market than could be achieved by a stand- system as demand rises over summer. -

Australian Pipeline Trust

Australian Pipeline Ltd ACN 091 344 704 | Australian Pipeline Trust ARSN 091 678 778 | APT Investment Trust ARSN 115 585 441 Level 25, 580 George Street Sydney NSW 2000 | PO Box R41 Royal Exchange NSW 1225 Phone +61 2 9693 0000 | Fax +61 2 9693 0093 APA Group | apa.com.au 22 August 2018 ASX ANNOUNCEMENT APA Group (ASX: APA) (also for release to APT Pipelines Limited (ASX: AQH)) Annual Financial Results The following announcements are attached: • Australian Pipeline Trust Appendix 4E • Australian Pipeline Trust Annual Report • APT Investment Trust Annual Report • Sustainability Report Nevenka Codevelle Company Secretary Australian Pipeline Limited For further information please contact: Investor enquiries: Media enquiries: Jennifer Blake Louise Watson Telephone: +61 2 9693 0097 Telephone: +61 2 8011 0591 Mob: +61 455 071 006 Mob: +61 419 185 674 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] About APA Group (APA) APA is a leading Australian energy infrastructure business, owning and/or operating in excess of $20 billion of energy infrastructure assets. Its gas transmission pipelines span every state and territory on mainland Australia, delivering approximately half of the nation’s gas usage. APA has direct management and operational control over its assets and the majority of its investments. APA also holds ownership interests in a number of energy infrastructure enterprises including SEA Gas Pipeline, SEA Gas (Mortlake) Partnership, Energy Infrastructure Investments and GDI Allgas Gas Networks. APTFor personal use -

Managing System Strength During the Transition to Renewables

Managing system strength during the transition to renewables GHD ADVISORY i GHD Report for ARENA - Managing system strength during the transition to renewables Acknowledgement This project received funding from ARENA as part of ARENA's Advancing Renewables Program. Disclaimer The funding for this report was secured from the Australia Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) by Powerlink Queensland along with its project partners, GHD, Pacific Hydro and Sun Metals. While the comments of the project partners were taken into consideration in the preparation of this report, the final report is independently authored by GHD. GHD disclaims responsibility to any person in connection with this report. GHD also excludes implied warranties and conditions, to the extent legally permissible. The services undertaken by GHD in connection with preparing this report were limited to those specifically detailed in the report and are subject to the scope limitations set out in the report. The opinions, conclusions and any recommendations in this report are based on conditions encountered and information reviewed at the date of preparation of the report. GHD has no responsibility or obligation to update this report to account for events or changes occurring subsequent to the date that the report was prepared. The opinions, conclusions and any recommendations in this report are based on assumptions GHD has made in this report. GHD disclaims liability arising from any of the assumptions being incorrect. GHD has prepared this report on the basis of information provided by various parties, which GHD has not independently verified or checked beyond the agreed scope of work. GHD does not accept liability in connection with such unverified information, including errors and omissions in the report caused by errors or omissions in that information. -

BRIEFING on DRAFT REPORT 12 October 2016

Queensland BRIEFING ON Renewable Energy Expert Panel DRAFT REPORT 12 October 2016 1 The panel COLIN ALLISON PAUL AMANDA PAUL MUGGLESTONE WARBURTON HYSLOP MCKENZIE MEREDITH 12/10/2016 2 Overarching themes Short-term QLD likely to Longer term Project pipeline opportunity to attract significant policy should be will need to grow leverage funding renewable flexible and to meet 50% under national investment adaptable LRET QLD likely to see 4,000-5,500 MW of large-scale Govt should encourage the Govt should work considerable investment renewable capacity required market to deliver renewable proactively to support the over the coming years from 2021-2030 to reach 50% energy projects utilising development of integrated Around 2,500 MW of by 2030 LRET funding up to 2020 climate and energy policies projects in the pipeline Generation capacity to meet the Subject to actual delivery of at the national level to target could be lower than 5,500 projects, Govt may consider maximise efficiencies and MW depending on future load reverse auctions for up to uptake of renewable requirements in QLD 400 MW energy Private sector should be QLD approach should be encouraged to contract and adaptable and flexible to scale up or down 12/10/2016 build renewable energy 3 wherever possible Queensland has a strong renewable resource potential SOLAR IRRADIATION WIND SPEED AT 80 METRES Average annual sun, period 2007-2012 Wind speed (meters/second) <1,100 1,300 1,500 1,700 1,900 2,100 2,300 > kWh/m2 4.3 5.6 5.8 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.9 7.0 7.2 7.8 9.6 12/10/2016