Working Class Susceptibility to the NSDAP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 5. Between Gleichschaltung and Revolution

Chapter 5 BETWEEN GLEICHSCHALTUNG AND REVOLUTION In the summer of 1935, as part of the Germany-wide “Reich Athletic Com- petition,” citizens in the state of Schleswig-Holstein witnessed the following spectacle: On the fi rst Sunday of August propaganda performances and maneuvers took place in a number of cities. Th ey are supposed to reawaken the old mood of the “time of struggle.” In Kiel, SA men drove through the streets in trucks bearing … inscriptions against the Jews … and the Reaction. One [truck] carried a straw puppet hanging on a gallows, accompanied by a placard with the motto: “Th e gallows for Jews and the Reaction, wherever you hide we’ll soon fi nd you.”607 Other trucks bore slogans such as “Whether black or red, death to all enemies,” and “We are fi ghting against Jewry and Rome.”608 Bizarre tableau were enacted in the streets of towns around Germany. “In Schmiedeberg (in Silesia),” reported informants of the Social Democratic exile organization, the Sopade, “something completely out of the ordinary was presented on Sunday, 18 August.” A no- tice appeared in the town paper a week earlier with the announcement: “Reich competition of the SA. On Sunday at 11 a.m. in front of the Rathaus, Sturm 4 R 48 Schmiedeberg passes judgment on a criminal against the state.” On the appointed day, a large crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Th e Sopade agent gave the setup: “A Nazi newspaper seller has been attacked by a Marxist mob. In the ensuing melee, the Marxists set up a barricade. -

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

La Dialectique Néo-Fasciste, De L'entre-Deux-Guerres À L'entre-Soi

La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi. Nicolas Lebourg To cite this version: Nicolas Lebourg. La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi.. Vocabulaire du Politique : Fascisme, néo-fascisme, Cahiers pour l’Analyse concrète, Inclinaison-Centre de Sociologie Historique, 2006, pp.39-57. halshs-00103208 HAL Id: halshs-00103208 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00103208 Submitted on 3 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 La Dialectique néo-fasciste, de l’entre-deux-guerres à l’entre-soi. Le siècle des nations s’achève en 1914. La Première Guerre mondiale produit d’une part une volonté de dépassement des antagonismes nationalistes, qui s’exprime par la création de la Société des Nations ou le vœu de construction européenne, d’autre part une réaction ultra-nationaliste. Au sein des fascismes se crée, en chaque pays, un courant marginal européiste et sinistriste1. Dans les discours de Mussolini, l’ultra-nationalisme impérialiste cohabite avec l’appel à l’union des « nations prolétaires » contre « l’impérialisme » et le « colonialisme » de « l’Occident ploutocratique » – un discours qui, après la naissance du Tiers-monde, paraît généralement relever de l’extrémisme de gauche. -

![Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9515/autarky-and-lebensraum-the-political-agenda-of-academic-plant-breeding-in-nazi-germany-1-289515.webp)

Autarky and Lebensraum. the Political Agenda of Academic Plant Breeding in Nazi Germany[1]

Journal of History of Science and Technology | Vol.3 | Fall 2009 Autarky and Lebensraum. The political agenda of academic plant breeding in Nazi Germany[1] By Thomas Wieland * Introduction In a 1937 booklet entitled Die politischen Aufgaben der deutschen Pflanzenzüchtung (The Political Objectives of German Plant Breeding), academic plant breeder and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (hereafter KWI) for Breeding Research in Müncheberg near Berlin Wilhelm Rudorf declared: “The task is to breed new crop varieties which guarantee the supply of food and the most important raw materials, fibers, oil, cellulose and so forth from German soils and within German climate regions. Moreover, plant breeding has the particular task of creating and improving crops that allow for a denser population of the whole Nordostraum and Ostraum [i.e., northeastern and eastern territories] as well as other border regions…”[2] This quote illustrates two important elements of National Socialist ideology: the concept of agricultural autarky and the concept of Lebensraum. The quest for agricultural autarky was a response to the hunger catastrophe of World War I that painfully demonstrated Germany’s dependence on agricultural imports and was considered to have significantly contributed to the German defeat in 1918. As Herbert Backe (1896–1947), who became state secretary in 1933 and shortly after de facto head of the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture, put it: “World War 1914–18 was not lost at the front-line but at home because the foodstuff industry of the Second Reich [i.e., the German Empire] had failed.”[3] The Nazi regime accordingly wanted to make sure that such a catastrophe would not reoccur in a next war. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

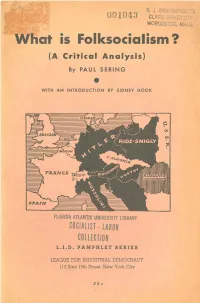

What Is Folksocialism? (A Critical Analysis)

001043 What is Folksocialism? (A Critical Analysis) By PAUL SERING • WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIDNEY HOOK . f' SPAIN flORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SOCIALIST· LABOR COLLECTION L.LD. PAMPHLET SERIES LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street, New York City 25c I HE LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY is a membership society en· T gaged in education toward a social order based on production for use and not for profit. To this end the League conducts research, lecture and information services, suggests practical plans for increasing social con· trol, organizes city chapters, publishes books and pamphlets on problems of industrial democracy, and sponsors conferences, forums, luncheon dis cussions and radio talks in leading cities where it has chapters. r-------.lTs OFFICERS FOR 1936-1937 ARE:--------, PRESIDENT ROBERT MORSS LOVETT VICE-PRESIDENTS JOHN DEWEY ALEXANDER MEIKLEJOHN JOHN HAYNES HOLMES MARY R. SANFORD JAMES H. MAURER VIDA D. SCUDDER FRANCIS J. McCONNELL HELEN PHELPS STOKES TB.EASUJlEB STUART CHASE • EXECUTIYE DIBECTORS NORMAN THOMAS HARRY W. LAIDLER EXJ:Cl7TIVB UCBIITAIlY ORGANIZATION SIlCIIETABY MARY FOX MARY W. HILLYER • ..hrinant SecretaTJI Chapter Secretariu CHARLES ENOVALL BERNARD KIRBY. Chlcago SIDNEY SCHULMAN. Phlla. ETHAN EDLOFF. Detroit Emerge1lCV Committee for Striker" Relief ROBERT O. MENAKER 000 LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street New York City, N. Y. COPYRIGHT 1937 by the LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL......... DEMOCRACY WHAT IS FOLKsOCIALlsM? (A Critical Analysis) BY PAUL SERING WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIDNEY HOOK • TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY HARRIET YOUNG AND MARY Fox • Published by LEAGUE FOR INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY 112 East 19th Street, New York City February, 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION " 7 WHAT Is FOLKSOCIALISM? (A Critical Analysis) ~ 12 I. -

The Buildup of the German War Economy: the Importance of the Nazi-Soviet Economic Agreements of 1939 and 1940 by Samantha Carl I

The Buildup of the German War Economy: The Importance of the Nazi-Soviet Economic Agreements of 1939 and 1940 By Samantha Carl INTRODUCTION German-Soviet relations in the early half of the twentieth century have been marked by periods of rapprochement followed by increasing tensions. After World War I, where the nations fought on opposite sides, Germany and the Soviet Union focused on their respective domestic problems and tensions began to ease. During the 1920s, Germany and the Soviet Union moved toward normal relations with the signing of the Treaty of Rapallo in 1922.(1) Tensions were once again apparent after 1933, when Adolf Hitler gained power in Germany. Using propaganda and anti-Bolshevik rhetoric, Hitler depicted the Soviet Union as Germany's true enemy.(2) Despite the animosity between the two nations, the benefits of trade enabled them to maintain economic relations throughout the inter-war period. It was this very relationship that paved the way for the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1939 and the subsequent outbreak of World War II. Nazi-Soviet relations on the eve of the war were vital to the war movement of each respective nation. In essence, the conclusion of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact on August 23, 1939 allowed Germany to augment its war effort while diminishing the Soviet fear of a German invasion.(3) The betterment of relations was a carefully planned program in which Hitler sought to achieve two important goals. First, he sought to prevent a two-front war from developing upon the invasion of Poland. Second, he sought to gain valuable raw materials that were necessary for the war movement.(4) The only way to meet these goals was to pursue the completion of two pacts with the Soviet Union: an economic agreement as well as a political one. -

Gregor-Strasser-And-The-Organisation-Of-The-Nazi-Party-1925-32

I This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66—14,650 DIXON, Joseph Murdock, 1932- GREGOR STRASSER AND THE ORGANIZATION OF THE NAZI PARTY, 1925-32. Stanford University, Ph.D., 1966 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc.,Ann Arbor, Michigan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GREGOR STRASSER AND THE ORGANIZATION OF THE NAZI PARTY, 1925-32 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Joseph Murdock Dixon June 1966 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. cfY'<?L(rr< / A , . C. I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree - ™ ™ •’ 7 I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Approved for the University Committee on the Graduate Division: /r. Dean of/theo 7 Graduate Division ii Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. GREGOR STRASSER AND THE NSDAP PRIOR TO 1925 . 1 II. THE NORTHERN ORGANIZATION PRIOR TO STRASSER . 45 HI. -

Cr^Ltxj

THE NAZI BLOOD PURGE OF 1934 APPRCWBD": \r H M^jor Professor 7 lOLi Minor Professor •n p-Kairman of the DeparCTieflat. of History / cr^LtxJ~<2^ Dean oiTKe Graduate School IV Burkholder, Vaughn, The Nazi Blood Purge of 1934. Master of Arts, History, August, 1972, 147 pp., appendix, bibliography, 160 titles. This thesis deals with the problem of determining the reasons behind the purge conducted by various high officials in the Nazi regime on June 30-July 2, 1934. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, and others used the purge to eliminate a sizable and influential segment of the SA leadership, under the pretext that this group was planning a coup against the Hitler regime. Also eliminated during the purge were sundry political opponents and personal rivals. Therefore, to explain Hitler's actions, one must determine whether or not there was a planned putsch against him at that time. Although party and official government documents relating to the purge were ordered destroyed by Hermann GcTring, certain materials in this category were used. Especially helpful were the Nuremberg trial records; Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939; Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945; and Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1934. Also, first-hand accounts, contem- porary reports and essays, and analytical reports of a /1J-14 secondary nature were used in researching this topic. Many memoirs, written by people in a position to observe these events, were used as well as the reports of the American, British, and French ambassadors in the German capital.