A"Review"Of"Khalad"Hussain’S" Against(The(Grain" By#Duane#Alexander#Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Methodology and Sample Background 8

VOICES FROM CHRISTIANS IN BRITAIN WITH A MUSLIM BACKGROUND: STORIES FOR THE BRITISH CHURCH ON EVANGELISM, CONVERSION, INTEGRATION AND DISCIPLESHIP By Thomas J. Walsh A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree MA in Mission Birmingham Christian College Birmingham, England September 2005 1 I dedicate this work to Martin my friend And all my Navigator colleagues To advance the gospel of Jesus and his kingdom Into the nations Through spiritual generations of labourers Living and discipling among the lost 2 Acknowledgements Thanks are due to a large number of people who have to put up with me but who make my life more enjoyable than they can imagine. In some cases they have just kept me going The Sanctuary Team and the Koinonia Group……thanks for the partnership Our Small Group……whose commitment to Judi and I amazes us Allan, Cathie, Peter, Gillian and Judy……special Navigator colleagues and friends who have shared our exile in Birmingham, a great city John and Catherine…..always an inspiration Nasrine….our closest, best and dearest Muslim friend Staff at BCC and especially Mark…..who showed me what good criticism really is The MBBs who took part in this research…..special people indeed Our faithful and loyal financial supporters….thank you so much My family especially Andy and Dave…..always great to see you Janet…..our special friend And finally Judi……words are insufficient 3 CONTENTS TITLE PAGE 1 DEDICATION 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 1 THE IDEA OF VOICES 5 CHAPTER 2 METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE BACKGROUND 8 A. Methodology 8 B. -

Teaching Christians About Islam : a Study in Methodology, Appendix 5

C CROSS AND CRESCENT: RESPONDING TO THE CHALLENGE OF ISLAM by COL IN CHAPMAN DRAFT MANUSCRIPT OF A BOOK TO BE PUBLISHED BY INTER-VARSITY PRESS Submitted in conjunction with the thesis TEACHING CHRISTIANS ABOUT ISLAM: A STUDY IN METHODOLOGY to the Department of Theology of the University of Birmingham Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, Selly Oak BIRMINGHAM September 1993 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. CROSS and CRESCENT; RESPONDING TO THE CHALLENGE OF ISLAM INTRODUCTION Part 1. RELATING TO OUR MUSLIM NEIGHBOURS 1. Meeting face to face 2. Appreciating their culture 3. Examining our attitudes 4. Visiting a mosque 5. Facing immediate issues 6. Bible Study Part 2. UNDERSTANDING ISLAM 1. The Muslim at prayer 2. Basic Muslim beliefs and practices 3. The Qur'an 4. Muhammad 5. Tradition 6. Law and theology 7. Sub-Groups in Islam 8. Suflsm 9. 'Folk Islam' or 'Popular Islam' 10. The spread and development of Islam TiT Is1 am in the modern world 12. Women in Islam Part 3. ENTERING INTO DISCUSSION AND DIALOGUE 1. -

|||GET||| I Dared to Call Him Father the Miraculous Story of a Muslim

I DARED TO CALL HIM FATHER THE MIRACULOUS STORY OF A MUSLIM WOMANS ENCOUNTER WITH GOD 25TH EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Bilquis Sheikh | 9780800793241 | | | | | Book Review: I Dared to Call Him Father; The Miraculous Story a Woman’s Encounter with God Bilquis shares the struggles she faced as a young Christian. At another time her grandson, Mahmud, became so listless that one of her friends wanted her to call the village mullah and ask him to pray for Mahmud. Her family started coming to her house and trying to talk to her I Dared to Call Him Father The Miraculous Story of a Muslim Womans Encounter with God 25th edition she prayed scripture and found new I Dared to Call Him Father The Miraculous Story of a Muslim Womans Encounter with God 25th edition. Enjoyed it! The 25th anniversary edition includes an afterword by a missionary friend of Bilquis who plays a prominent role in the story and an appendix on how the East enriches the West. See more details at Online Price Match. Select Option. I thought that the last chapter in the book, Enriched by the East by Synnove Mitchell, was particularly good and instructive since it drew comparisons and contrasts between the Eastern and Western cultures. She was so sorry and repentent about her sin: selfishness, pride, arrogance, and unwillingness to forgive. Overall, this is a high-quality, well-written biography of a brave and memorable lady. The 25th anniversary edition includes an afterword by a missionary friend of Bilquis who plays a prominent role in the story and an appendix on how the East enriches the West. -

World Geography

Hearts for Him Through High School: World Geography A Compelling High School Program that will encourage you to open the door, get ready to explore, and journey forth into this world! Written to send forth students ages 13-15 everywhere armed with knowledge, filled with compassion, and consumed with love for those around the world, around the neighborhood, or just around the corner. [11th and 12th grade students can also use this guide by adjusting the 3R’s and science as needed] Explore unchartered lands and seas…discover Simply customize this program by choosing whichever indescribeable treasures of old and new…solve untold packages you need! mysteries of past and present…and journey to exotic The “Learning Through History” part of the program sets places spanning from one end of the earth to the other you off on an adventure of a chronological and narrative view as you take a tour through time via World Geography! of World Geography. You will not only travel the world with Embark on an exploration of history and with pen in the resources described above, but you will also embark on a hand chronicle your journey by Mapping journey to answer the question, But Don’t All the World With Art and by making Religions Lead to God? With World Religions memorable entries in your full-color – An Indispensable Introduction tucked under Expedition Journal. Join archaeologists your arm, navigate the multi-faith maze by to search for answers to uncover the using your newfound knowledge of 8 of meaning of artifacts, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the world’s major religions to reach out to and the historocity of the Bible. -

Encounter with Folk Islam (1)

Vivienne Stacey on Spiritual Warfare Encounter with Folk Islam (1) “Working for many years in a Muslim country, I have come to the conclusion that the power of Islam does not lie in its dogma and practices, nor in the antithesis of the Trinity against the Lordship of Christ and His redeeming death, but in the occult practices of its leaders, thus holding sway over their people.” So wrote Detmar Scheunemann about his ministry in Indonesia, in Let the Earth Hear His Voice page 885, Minneapolis: World Wide Publications, 1975. A study of the quarterly journal The Muslim World since its beginning in 1911 would confirm this view. Many articles from Christian workers in Muslim lands appeared until the late 1930s, eg: - The cult of saints in Islam Professor Goldziher. Vol 1, No 3, p 302, July 1911 Popular Islam in Bengal and How to Approach It. John Takle. Vol 4, No 4, p 379, Oct 1914 Islam and Magic in Egypt Herbert E E Hayes. Vol 4, No 4, p 396, Oct 1914 Saint Worship in North Africa E Montet. Vol 3, No 3, p 242, July 1913 The Familiar Spirit or Qarina S M Zwemer. Vol 6, No 4, p 360, Oct 1916 Animism in Islam (Hair, finger nails and the Hand) S M Zwemer. Vol 7, No 3, p 245, July 1917 Amulets in Egypt Vol 7, No 4, p 366, Oct 1917 Animistic Elements in Moslem Prayer S M Zwemer. Vol 8, No 4, p 358, Oct 1918 Animism in the Creed, and in the use of the Book and the Rosary S M Zwemer. -

To Call Him Father

Sheikh_Dared_KK_BB 1/7/03 8:13 AM Page 3 I DARED TO CALL HIM FATHER THE MIRACULOUS STORY OF A MUSLIM WOMAN’S ENCOUNTER WITH GOD Bilquis Sheikh with Richard H. Schneider c Sheikh_Dared_KK_BB 1/7/03 8:13 AM Page 4 © 1978, 2003 by Bilquis Sheikh Published by Chosen Books A division of Baker Book House Company P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.bakerbooks.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-8007-9324-2 Old Testament Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible. Unless otherwise indicated, New Testament Scripture quotations are from the New Testament in Modern English, translated by J. B. Phillips. Copyright 1958, 1960, 1972 by J. B. Phillips. Used by permission of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. Scripture marked NASB is taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE ®. Copyright © The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Used by permission. Scripture marked NIV is taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Soci- ety. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. The verse by Rudyard Kipling is excerpted from Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Defini- tive Edition. -

Going Public with Faith in a Muslim Context: Lessons from Esther by Jeff Nelson

Religion and Identity Going Public with Faith in a Muslim Context: Lessons from Esther by Jeff Nelson issiologists and practitioners among Muslim converts continue to grapple with the question of self-identity within threatening religious environments.1 I suggest that we take this discussion of Midentity a step further and begin to explore the manner and timing of a convert’s self-disclosure. This article examines the story of Esther and her mentor, Mor- decai, to explore a critical strategy of advising secret believers, a critical decision concerning self-disclosure, and the influence of a critical mass of public believers in leading many others to faith. The article also considers the role of critical men- torship in advising Muslim background believers on the timing of self-disclosure. How or when should a secret believer make her faith public? At what point should a man identify himself as a Christ follower? Those working among Muslims often struggle to know how to advise converts on this issue because of the tension between biblical commands to confess one’s faith and the cul- tural realities of persecution or martyrdom. The story of Esther from the Hebrew Scriptures has parallels with the issue of self-disclosure of Muslim converts and implications for their mentors as Jeff Nelson, with his wife Janelle and well. The parallels include a people group threatened due to their identity their four children, has served with Assemblies of God World Missions with God; laws that support the persecution and death of the people of God; in Nairobi, Kenya since 2001. -

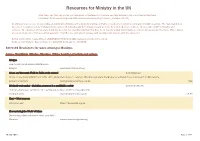

Resources for Ministry in the UK

Resources for Ministry in the UK How, then, can they call on the one they have not believed in? And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? (Romans 10: 14) As Christians, we believe in welcoming all, building friendships and sensitively sharing our Faith, in obedience to Christ’s command in Matthew 28:19. The materials below have been recommended by Christians from various UK networks and denominations and we hope they will help you to relate to other people of different faiths and cultures. The inclusion of materials in this list does not necessarily imply that they have been read by Global Connections or endorsed by Global Connections. Where prices are given, please note that we cannot guarantee that they are correct and postage and packing costs may be added to any order. Global Connections, Caswell Road, LEAMINGTON SPA CV31 1QD, www.globalconnections.org.uk Registered in England Wales Charity no. 1081966 Company no. 3886596 Selected Resources for work amongst Muslims Asians /Buddhists /Hindus /Muslims /Sikhs: Looking at beliefs and culture Bridges How to build relationships with Muslims Bridges www.crescentproject.org Cross and Crescent (Faith to Faith study course) Colin Chapman Study course, helping Christians in the UK to understand Islam, to relate to Muslims and share the Gospel as a friend. Free download from GC website. Global Connections www.globalconnections.org.uk free Distinctly welcoming - Christian presence in a multifaith society Richard Sudworth Help for all who lack confidence in reaching out to those of different backgrounds Scripture Union www.scriptureunion.org.uk £9.99 East + West courses Interserve GBI https://www.kitab.org.uk Encountering the World of Islam Discovering Islam and how to share your faith Pioneers www.encounteringislam.org 26 July 2018 Page 1 of 21 Selected Resources for work amongst Muslims Faith to Faith study courses Available on Buddhism, Chinese Religions, Islam and Sikhism. -

I Dared to Call Him Father: the Miraculous Story of a Muslim

To my grandson Mahmud my little prayer partner who has been a source of joy and comfort to me through many lonely hours. Foreword 9 1. A Frightening Presence 15 2. The Strange Book 26 3. The Dreams 33 4. The Encounter 39 5. The Crossroads 52 6. Learning to Find His Presence 60 7. The Baptism of Fire and Water 70 8. Was There Protection? 81 9. The Boycott 94 10. Learning to Live in the Glory 105 11. Winds of Change 123 12. A Time for Sowing 131 13. Storm Warnings 142 14. Flight 160 Epilogue 170 My initial impression of Madame Bilquis Sheikh of Pakistan was of her large, expressive, luminous eyes. I saw pain written there, and compassion, and rare sensitivity to the world of the spirit. A woman of mysterious age with hints of gray in her hair, she was wearing a beautiful sari with dignity and grace. There was about her the unmistakable aura of having been born to wealth and position. Her voice was the deepest with the most resonant timbre I have ever heard in a woman. Our first meeting took place in the mirrored dining room of a Bel Air, California, restaurant. That day I heard the outline of Madame Sheikh's amazing story. Many another's adventure can perhaps equal hers in dramatic content, but few in one respect: only rarely does the sovereign God interrupt the flow of history to reach down and reveal Himself to a human being in such unmistakable fashion as He did with her. The element of initiative from the Godward side was so startling as to be reminiscent of Saul of Tarsus' experience on the road to Damascus. -

Dreams and Visions As Divine Revelation

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2010 Dreams and Visions as Divine Revelation Sarah Horton Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Horton, Sarah, "Dreams and Visions as Divine Revelation" (2010). Honors Theses. 42. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/42 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DREAMS AND VIS IONS AS DIVINE REVELATION BY SARAH HORTON OUACHITA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT ARE DREAMS AND VISIONS? ................................................................................................................. 2 THE BIBLICAL PRECEDENT ................................................................................................................................ 4 OLD TESTAME T PERIOD ........................................................................................................... .. 5 NEW TESTAMENT.. ....................................................................................................................... 7 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................. -

The Following Pages Were Presented at the Building Bridges with Muslims Event Spon- Sored by Tabernacle EPC in October of 2016

Building Bridges The following pages were presented at the Building Bridges with Muslims event spon- sored by Tabernacle EPC in October of 2016. Rev Mark Vanderput (iLoveMuslims.net) was the presenter. Mark is also one of our EPC World Outreach Missionaries. These have been made available to NCECP with Mark’s permission. “ISLAM, JESUS, AND YOU” INTRODUCTION Which word(s) best describes your reaction to the words “Muslim” or “Islam”: curiosity, fear, anger, or indifference? What are three adjectives you would use to describe Muslims? What core beliefs/religious practices do you associate with them? Have you made attempts to discuss faith issues with Muslims in your neighborhood, workplace, or school? Describe your experiences. “Islam” is Arabic for “surrender” or “submission,” and a Muslim is a “surrendered one”. I. ISLAM: THE ORIGINS THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD/THE QUR’AN - Muhammad was born in A.D. 570 into a family believed to be descended from Abraham’s son, Ishmael. His father died before his birth, his mother died when he was 6. He was appalled at the idol worship of his day. In a time of meditation in a cave outside Mecca, Muslims believe he was visited by the angel Gabriel and that from there until the end of his life in 632, he received revelations which were compiled into the “Qur’an.” The Qur’an is 114 chapters (suras) and is considered the last, infallible witness of Allah — an exact word-for-word copy of God’s final revelation. MUHAMMAD’S REACTIONS TO THE REVELATIONS AND VISIT WITH A “CHRISTIAN” – When Muhammad received revelations from the “angel,” he had numerous negative reactions: panic, terror; sweating profusely; ringing in the ears; foaming at the mouth; trembling; loss of consciousness or fainting; bewilderment - fear that he was possessed by a demon or going mad; suicidal depression. -

35:4 Clarifying the Frontiers

The Journal of the International Society for Frontier Missiology Int’l Journal of Frontier Missiology Clarifying the Frontiers 151 From the Editor’s Desk Brad Gill Negotiating the Edges of the Kingdom 154 Articles 154 Clarifying the Remaining Frontier Mission Task R. W. Lewis Accurate, graphic data forces a reappraisal of mission. 171 Adaptive Missiological Engagement with Islamic Contexts Warrick Farah Vanquishing a modern “one-size-fits-all” mentality 179 Beyond Groupism: Refining Our Analysis of Ethnicity and Groups Brad Gill Can we think ethnicity without groups? 185 Five Key Questions: What Hearers Always Want to Know as They Consider the Gospel T. Wayne Dye and Danielle Zachariah Conceiving a “cultural apologetic” for cross-cultural communication 194 Book Reviews 194 Christianity in the Twentieth Century: A World History 197 Beyond Caste: Identity and Power in South Asia, Past and Present 202 In Others’ Words 202 A Divisive New Statement on Social Justice Revival of Religion in a Secular China “At First They Came For . .” Marginalized Ethnic Groups: Lessons from North African Church History Crackdown on Dissent, Crack-Up of Democracy? c3October–December5:4 2018 Negotiating the Edges of the Kingdom October–December 2018 Volume 35:4 he Apostle Paul looms large in any attempt to clarify the frontier Editor mission task; he’s our biblical exemplar. We’re drawn to his vision Brad Gill statement in Romans 15 where he claims, “I have fulfilled the gospel Consulting Editors Rick Brown, Rory Clark, Darrell Dorr, Tof Christ” (v. 19). Paul had ministered the name of Jesus from Jerusalem to Gavriel Gefen, Herbert Hoefer, Illyricum, in synagogues and temples, to Greek and barbarian, in urban hubs R.