Dreams and Visions As Divine Revelation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

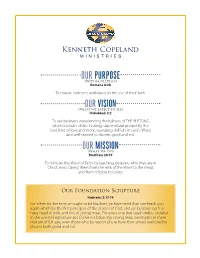

2018 KCM Purpose Vision Mission Statement.Indd

OUR PURPOSE (Why KCM Exists) Romans 8:28 To mature believers worldwide in the use of their faith. OUR VISION (What We Expect to See) Habakkuk 2:2 To see believers experiencing the fullness of THE BLESSING which includes divine healing, supernatural prosperity, the God kind of love and more; operating skillfully in God’s Word; and well-trained to discern good and evil. OUR MISSION (What We Do) Matthew 28:19 To minister the Word of Faith, by teaching believers who they are in Christ Jesus; taking them from the milk of the Word to the meat, and from religion to reality. Our Foundation Scripture Hebrews 5:12-14 For when for the time ye ought to be teachers, ye have need that one teach you again which be the first principles of the oracles of God; and are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat. For every one that useth milk is unskilful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil. STATEMENT OF FAITH • We believe in one God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Creator of all things. • We believe that the Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, was conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, was crucified, died and was buried; He was resurrected, ascended into heaven and is now seated at the right hand of God the Father and is true God and true man. -

Speaking in Tongues

SPEAKING IN TONGUES “He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself” 1 Corinthians 14:4a Grace Christian Center 200 Olympic Place Pastor Kevin Hunter Port Ludlow, WA 8365 360 821 9680 mailing | 290 Olympus Boulevard Pastor Sherri Barden Port Ludlow, WA 98365 360 821 9684 Pastor Karl Barden www.GraceChristianCenter.us 360 821 9667 Our Special Thanks for the Contributions of Living Faith Fellowship Pastor Duane J. Fister Pastor Karl A. Barden Pastor Kevin O. Hunter For further information and study, one of the best resources for answering questions and dealing with controversies about the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the gift of speaking in tongues is You Shall Receive Power by Dr. Graham Truscott. This book is available for purchase in Shiloh Bookstore or for check-out in our library. © 1996 Living Faith Publications. All rights reserved. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Unless otherwise identified, scripture quotations are from The New King James Version of the Bible, © 1982, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. IS SPEAKING IN TONGUES A MODERN PHENOMENON? No, though in the early 1900s there indeed began a spiritual movement of speaking in tongues that is now global in proportion. Speaking in tongues is definitely a gift for today. However, until the twentieth century, speaking in tongues was a commonly occurring but relatively unpublicized inclusion of New Testament Christianity. Many great Christians including Justin Martyr, Iranaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, Chrysostom, Luther, Wesley, Finney, Moody, etc., either experienced the gift themselves or attested to it. Prior to 1800, speaking in tongues had been witnessed among the Huguenots, the Camisards, the Quakers, the Shakers, and early Methodists. -

Chapter 2 Methodology and Sample Background 8

VOICES FROM CHRISTIANS IN BRITAIN WITH A MUSLIM BACKGROUND: STORIES FOR THE BRITISH CHURCH ON EVANGELISM, CONVERSION, INTEGRATION AND DISCIPLESHIP By Thomas J. Walsh A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree MA in Mission Birmingham Christian College Birmingham, England September 2005 1 I dedicate this work to Martin my friend And all my Navigator colleagues To advance the gospel of Jesus and his kingdom Into the nations Through spiritual generations of labourers Living and discipling among the lost 2 Acknowledgements Thanks are due to a large number of people who have to put up with me but who make my life more enjoyable than they can imagine. In some cases they have just kept me going The Sanctuary Team and the Koinonia Group……thanks for the partnership Our Small Group……whose commitment to Judi and I amazes us Allan, Cathie, Peter, Gillian and Judy……special Navigator colleagues and friends who have shared our exile in Birmingham, a great city John and Catherine…..always an inspiration Nasrine….our closest, best and dearest Muslim friend Staff at BCC and especially Mark…..who showed me what good criticism really is The MBBs who took part in this research…..special people indeed Our faithful and loyal financial supporters….thank you so much My family especially Andy and Dave…..always great to see you Janet…..our special friend And finally Judi……words are insufficient 3 CONTENTS TITLE PAGE 1 DEDICATION 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 1 THE IDEA OF VOICES 5 CHAPTER 2 METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE BACKGROUND 8 A. Methodology 8 B. -

Under the Reign of Doubt.Htm

Under the Reign of Doubt: Chaucer’s House of Fame and Narrative Authority Christopher B. Smith Department of English Villanova University Edited by Edward Pettit Geoffrey Chaucer’s House of Fame is an unusual poem by anyone’s set of standards. Its feast of colorful action and antic pace seem at times to overwhelm the reader, as it does the somewhat hapless narrator; for a rather brief work, it contains a great deal to puzzle over. That the text is made all the more baffling by an abrupt conclusion has led to much speculation from scholars regarding its finished or unfinished nature, especially pertaining to the identity of the man of great authority seen “atte laste” (The Riverside Chaucer 373, l. 2155), who, ironically, will remain indefinitely unseen. Attempting to whittle down critical concerns with the poem to this one question, however, would be overly reductive, just as showing aesthetic appreciation merely for the fanciful humor and bewildered awe that portions of Chaucer’s text exhibit — treating it as a sort of fantasy story with a mild moralistic bent on the capriciousness of fame — misses its deeper concerns. Stephen Knight sees the poem in contrast to the relatively simplistic Book of the Duchess, a work with an “unproblematic ideology,” as one with “epistemological, even ontological concerns”; rather poetically, he says it is “a winter dream” (Knight 28). If the knight of Book of the Duchess exhibited honor as an absolute (and likewise for the characters and relationships exhibited in Chaucer’s narrative forebears), the concept itself, as well as “the mechanics of fame,” are now illuminated as far more complex than in previous imaginings: just as the “physical nature of [an] inquiry” is dealt with in the vocabulary of medieval science, the work as a whole involves a highly developed philosophy (28-29). -

The Dream Vision: the Other As the Self

Linguistics and Literature Studies 6(2): 47-51, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2018.060201 The Dream Vision: The Other as the Self Natanela Elias Independent Scholar, Israel Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The Middle Ages were hardly known for their response. Dream visions form a literary combination of openness or willingness to accept the other, however, sleeping dreams and waking visions. In other words, the research indicates that things were not quite as they seemed. structure of the dream vision enables the necessary state of In this particular presentation, I would like to introduce the repose which ironically may lead to a re-awakening in the possibility of resolving conflict (social, political, religious) search for Truth. Barbara Newman [1] claims that dreams of via literature, and more specifically, through the use of the this kind, "like waking visions, focus less on predicting the popular medieval genre of the dream vision. future than on achieving self-knowledge, entering vividly into past events, or manifesting eternal truths”. Keywords Middle Ages, Self, Other, English literature, According to William Hodapp [2], and as we will try to John Gower delineate in this work, the structure of such visionary texts can be outlined "in four movements: first, the narrator describes an experience that suggested his initial psychological state; second, the narrator recounts a new 1. Introduction experience detailing a changed state of consciousness during which he encountered other characters; third, the narrator In our day and age, as we attempt to aspire to tolerance and describes an exchange, in this case as a dialogue between the acceptance, we must still acknowledge the existence of narrator and these other characters, through which he gained animosity, intolerance and discrimination. -

The Process of Salvation in <I>Pearl

Volume 37 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2018 The Process of Salvation in Pearl and The Great Divorce Amber Dunai Texas A&M University - Central Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dunai, Amber (2018) "The Process of Salvation in Pearl and The Great Divorce," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Analyzes the structural, aesthetic, and thematic parallels between C.S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce and the Middle English dream vision Pearl. By exploring the tension between worldly and heavenly conceptions of justice, value, and possession in The Great Divorce and Pearl, this study demonstrates Lewis’s skill at utilizing and updating medieval source material in order to respond to twentieth-century problems. -

'To Tellen Al My Dreme Aryght': Text World Theory and Reading The

‘To tellen al my dreme aryght’: Text World Theory and Reading the Medieval Dream Vision in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The House of Fame Jonathan Lobley The use of the dream vision in Chaucer’s The House of Fame (c.1387) (HoF) serves not only to transport the reader through the subconscious experience of the dreamer, but must also serve as a medium through which to expose the fragile platform of history and philosophy, a platform, as Stephen Russell suggests, that is built on the ‘tyranny of the written word’ (Russell 1988: 175). In an attempt to emulate the dream experience, Chaucer’s oneiric images and structure at times verge on the surreal. However, as T. S. Miller posits, despite the ‘disorientating shifts of scene and surprising imagery’, the HoF ‘remains structured by a sequence of distinct interior and exterior spaces through which its narrator-dreamer passes’ (Miller 2014: 480). Whilst this accounts for the spatio-temporal tracking of the narrator-dreamer within the text itself, literary criticism does not sufficiently explain the reader’s cognitive process as they attempt to map and construct their own cognitive model of the world in which the dreamer moves. Thus, this essay will use Marcello Giovanelli’s (2013) adaptation of Joanna Gavins’ (2005, 2007) and Paul Werth’s (1995, 1999) original Text World Theory (TWT) models to assess how a reader is manoeuvred through the abstract notion of a literary sleep-dream world. In doing so, I hope to uncover some limitations in the above Text World Theory models when applying them to Chaucer’s medieval dream vision. -

The Chaucerian Dream Vision and the Neoconservative Nightmare

Page 2 Strange Bedfellows: The Chaucerian Dream Vision and the Neoconservative Nightmare Drew Beard A dazedlooking young woman in a flowing white gown wanders down a suburban street, encountering a little girl in a frilly white dress; like the young woman, she is blond and we see that she has used chalk to sketch on the sidewalk the abandoned house standing before them. When asked if she lives there, the little girl giggles and says that ‘no one lives here.’ The young woman asks about ‘Freddy’ and is told: ‘He’s not home.’ In an instant, the sky darkens and it begins to rain heavily, washing away the chalk drawing of the little girl, who has disappeared. Reluctantly drawn into the house, the young woman finds herself trapped inside, surrounded by the anguished cries of children, as a tricycle comes crashing down the staircase. Attempting to escape, the young woman opens the front door and finds herself not outside but once again in the front hallway of this house of horrors, a nightmarish reimagining of a family home. As the door slams shut behind her, it becomes clear that there is no escape.(1) She is trapped inside the horrific dream vision that forms the narrative basis of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, the postmodern counterpart of the dream visions dating from the 14th century. Characterized by what Deanne Williams refers to as a ‘dynamic relation between text and commentary,’(2) the medieval ‘dream vision’ is defined by its allegorical orientation, an emphasis on the surreal or absurd, and a subjective and flexible reality. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

A"Review"Of"Khalad"Hussain’S" Against(The(Grain" By#Duane#Alexander#Miller

A"Bridge"between"Two"Worlds"and"Two" Faiths:"a"review"of"Khalad"Hussain’s" Against(the(Grain" By#Duane#Alexander#Miller### # # Mary’s"Well"Occasional"Papers( are(published(by(Nazareth( Evangelical(Theological( Seminary( # ! Director"of"Publications:"Duane"Alexander"Miller" Guest"Editor:"Edwin"Zehner" Citation:"" Miller,"Duane"Alexander."‘A"Bridge"between"Two"Worlds"and"Two"Faiths:"a"review"of" Khalad"Hussain’s"Against(the(Grain’"in"Mary’s(Well(Occasional(Papers,"4:1,"April" (Nazareth,"Israel:"Nazareth"Evangelical"Theological"Seminary"2015)." Key"Words:"" Religious"Conversion,"Kashmir,"Pakistan,"autobiography,"exYMuslim,"Pakistani" diaspora" A Bridge between Two Worlds and Two Faiths: a review of Khalad Hussain’s Against the Grain Duane Alexander Miller A review of Against the Grain by Khalad Hussain (Xlibris 2012, 218 pages) In the past ten years there has been a significant increase in the number of conversion narratives from Islam to Christianity (and vice versa).1 In this volume, Kashmiri convert Khalad Hussain makes his own contribution to this growing body of literature. My own doctoral work2 through the University of Edinburgh lead me to delve deeply into the literature of converts from Islam to Christianity. This included an analytical article on Saiid Rabiipour’s Farewell to Islam (2009), published as ‘”It is okay to question Allah”: the theology of freedom of Saiid Rabiipour, a Christian ex-Muslims.’3 As with most articles I publish I shared this on my professional blog,4 and it was by this means that Mr. Hussain contacted me and asked me if I would be interested in reviewing his own autobiography. The book begins with a depiction of the bucolic life led by his family in his hometown in the Mirpur region of Pakistani Kashmir. -

The English Dream Vision

The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM By J. Stephen Russell The first-person dream-frame nar rative served as the most popular English poetic form in the later Mid dle Ages. In The English Dream Vision, Stephen Russell contends that the poetic dreams of Chaucer, Lang- land, the Pearl poet, and others employ not simply a common exter nal form but one that contains an internal, intrinsic dynamic or strategy as well. He finds the roots of this dis quieting poetic form in the skep ticism and nominalism of Augustine, Macrobius, Guillaume de Lorris, Ockham, and Guillaume de Conches, demonstrating the interdependence of art, philosophy, and science in the Middle Ages. Russell examines the dream vision's literary contexts (dreams and visions in other narratives) and its ties to medieval science in a review of medi eval teachings and beliefs about dreaming that provides a valuable survey of background and source material. He shows that Chaucer and the other dream-poets, by using the form to call all experience into ques tion rather than simply as an authen ticating device suggesting divine revelation, were able to exploit con temporary uncertainties about dreams to create tense works of art. continued on back flap "English, 'Dream Vision Unglisfi (Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 1988 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. Quotations from the works of Chaucer are taken from The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 80:3–4 July/October 2016 Table of Contents Forty Years after Seminex: Reflections on Social and Theological Factors Leading to the Walkout Lawrence R. Rast Jr. ......................................................................... 195 Satis est: AC VII as the Hermeneutical Key to the Augsburg Confession Albert B. Collver ............................................................................... 217 Slaves to God, Slaves to One Another: Testing an Idea Biblically John G. Nordling .............................................................................. 231 Waiting and Waiters: Isaiah 30:18 in Light of the Motif of Human Waiting in Isaiah 8 and 25 Ryan M. Tietz .................................................................................... 251 Michael as Christ in the Lutheran Exegetical Tradition: An Analysis Christian A. Preus ............................................................................ 257 Justification: Set Up Where It Ought Not to Be David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 269 Culture and the Vocation of the Theologian Roland Ziegler .................................................................................. 287 American Lutherans and the Problem of Pre-World War II Germany John P. Hellwege, Jr. .......................................................................... 309 Research Notes ............................................................................................... 333 The Gospel