The Process of Salvation in <I>Pearl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

The Middle English "Pearl"

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2014 Dreaming Of Masculinity: The iddM le English "Pearl" And The aM sculine Space Of New Jerusalem Kirby Lund Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Lund, Kirby, "Dreaming Of Masculinity: The iddM le English "Pearl" And The asM culine Space Of New Jerusalem" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 1682. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1682 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DREAMING OF MASCULINITY: THE MIDDLE ENGLISH PEARL AND THE MASCULINE SPACE OF NEW JERUSALEM by Kirby A. Lund Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2014 © 2014 Kirby Lund ii This thesis, submitted by Kirby Lund in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved. ____________________________________ Michelle M. Sauer, Chairperson ____________________________________ Sheryl O’Donnell, Committee Member ____________________________________ Melissa Gjellstad, Committee Member This thesis is being submitted by the appointed advisory committee as having met all of the requirements of the School of Graduate Studies at the University of North Dakota and is hereby approved. -

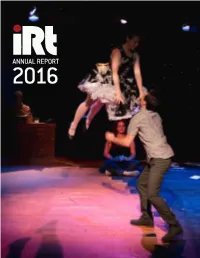

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 INSIDE Mission + History 3 Letter From IRT 4 Season Highlights 5 3B Development Series 7 Westside Experiment 20 Archive Residency 23 IRT Productions 26 Events/Workshops 27 After Residency 31 Photography Credits 32 Mission for Deaf artists. Second, IRT mentors the next gen- eration of theater artists through its educational IRT is a grassroots laboratory for independent theater program. Launched in 2012, Westside Experiment, and performance in New York City, providing space is a teen acting laboratory that pairs students with and support to a new generation of artists. Tucked working experimental theater artists to learn about away in the old Archive Building in Greenwich Village, their craft and create an original theater piece at IRT. IRT’s mission is to build a community of emerging and established artists by creating a home for the Some of the pioneering artists who have developed development and presentation of new work. work at IRT are: Young Jean Lee, Reggie Watts, Mike Daisey, New York Live Arts, Tommy Smith, Thomas HistorY Bradshaw, Crystal Skillman, Jose Zayas, May Adrales, terraNOVA Collective, Immediate Medium, Vampire In 2007, IRT Theater embarked on a groundbreaking Cowboys, The Nonsense Company/Rick Burkhardt, journey to support emerging and established artists, The Mad Ones, Collaboration Town, Rady&Bloom, to give young artists a unique opportunity to work Katt Lissard, Erica Fay and many others. with professionals, and to offer development and performance opportunities for Deaf artists and audi- Established in 1986 as Interborough Repertory ences. With new Artistic Director, Kori Rushton, the Theater by Luane Haggerty & Jonathan Fluck, IRT company created its artist in residency program & spent its first two decades nurturing artistic freedom completely revamped its staff & business model. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Under the Reign of Doubt.Htm

Under the Reign of Doubt: Chaucer’s House of Fame and Narrative Authority Christopher B. Smith Department of English Villanova University Edited by Edward Pettit Geoffrey Chaucer’s House of Fame is an unusual poem by anyone’s set of standards. Its feast of colorful action and antic pace seem at times to overwhelm the reader, as it does the somewhat hapless narrator; for a rather brief work, it contains a great deal to puzzle over. That the text is made all the more baffling by an abrupt conclusion has led to much speculation from scholars regarding its finished or unfinished nature, especially pertaining to the identity of the man of great authority seen “atte laste” (The Riverside Chaucer 373, l. 2155), who, ironically, will remain indefinitely unseen. Attempting to whittle down critical concerns with the poem to this one question, however, would be overly reductive, just as showing aesthetic appreciation merely for the fanciful humor and bewildered awe that portions of Chaucer’s text exhibit — treating it as a sort of fantasy story with a mild moralistic bent on the capriciousness of fame — misses its deeper concerns. Stephen Knight sees the poem in contrast to the relatively simplistic Book of the Duchess, a work with an “unproblematic ideology,” as one with “epistemological, even ontological concerns”; rather poetically, he says it is “a winter dream” (Knight 28). If the knight of Book of the Duchess exhibited honor as an absolute (and likewise for the characters and relationships exhibited in Chaucer’s narrative forebears), the concept itself, as well as “the mechanics of fame,” are now illuminated as far more complex than in previous imaginings: just as the “physical nature of [an] inquiry” is dealt with in the vocabulary of medieval science, the work as a whole involves a highly developed philosophy (28-29). -

The Dream Vision: the Other As the Self

Linguistics and Literature Studies 6(2): 47-51, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2018.060201 The Dream Vision: The Other as the Self Natanela Elias Independent Scholar, Israel Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The Middle Ages were hardly known for their response. Dream visions form a literary combination of openness or willingness to accept the other, however, sleeping dreams and waking visions. In other words, the research indicates that things were not quite as they seemed. structure of the dream vision enables the necessary state of In this particular presentation, I would like to introduce the repose which ironically may lead to a re-awakening in the possibility of resolving conflict (social, political, religious) search for Truth. Barbara Newman [1] claims that dreams of via literature, and more specifically, through the use of the this kind, "like waking visions, focus less on predicting the popular medieval genre of the dream vision. future than on achieving self-knowledge, entering vividly into past events, or manifesting eternal truths”. Keywords Middle Ages, Self, Other, English literature, According to William Hodapp [2], and as we will try to John Gower delineate in this work, the structure of such visionary texts can be outlined "in four movements: first, the narrator describes an experience that suggested his initial psychological state; second, the narrator recounts a new 1. Introduction experience detailing a changed state of consciousness during which he encountered other characters; third, the narrator In our day and age, as we attempt to aspire to tolerance and describes an exchange, in this case as a dialogue between the acceptance, we must still acknowledge the existence of narrator and these other characters, through which he gained animosity, intolerance and discrimination. -

'To Tellen Al My Dreme Aryght': Text World Theory and Reading The

‘To tellen al my dreme aryght’: Text World Theory and Reading the Medieval Dream Vision in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The House of Fame Jonathan Lobley The use of the dream vision in Chaucer’s The House of Fame (c.1387) (HoF) serves not only to transport the reader through the subconscious experience of the dreamer, but must also serve as a medium through which to expose the fragile platform of history and philosophy, a platform, as Stephen Russell suggests, that is built on the ‘tyranny of the written word’ (Russell 1988: 175). In an attempt to emulate the dream experience, Chaucer’s oneiric images and structure at times verge on the surreal. However, as T. S. Miller posits, despite the ‘disorientating shifts of scene and surprising imagery’, the HoF ‘remains structured by a sequence of distinct interior and exterior spaces through which its narrator-dreamer passes’ (Miller 2014: 480). Whilst this accounts for the spatio-temporal tracking of the narrator-dreamer within the text itself, literary criticism does not sufficiently explain the reader’s cognitive process as they attempt to map and construct their own cognitive model of the world in which the dreamer moves. Thus, this essay will use Marcello Giovanelli’s (2013) adaptation of Joanna Gavins’ (2005, 2007) and Paul Werth’s (1995, 1999) original Text World Theory (TWT) models to assess how a reader is manoeuvred through the abstract notion of a literary sleep-dream world. In doing so, I hope to uncover some limitations in the above Text World Theory models when applying them to Chaucer’s medieval dream vision. -

The Chaucerian Dream Vision and the Neoconservative Nightmare

Page 2 Strange Bedfellows: The Chaucerian Dream Vision and the Neoconservative Nightmare Drew Beard A dazedlooking young woman in a flowing white gown wanders down a suburban street, encountering a little girl in a frilly white dress; like the young woman, she is blond and we see that she has used chalk to sketch on the sidewalk the abandoned house standing before them. When asked if she lives there, the little girl giggles and says that ‘no one lives here.’ The young woman asks about ‘Freddy’ and is told: ‘He’s not home.’ In an instant, the sky darkens and it begins to rain heavily, washing away the chalk drawing of the little girl, who has disappeared. Reluctantly drawn into the house, the young woman finds herself trapped inside, surrounded by the anguished cries of children, as a tricycle comes crashing down the staircase. Attempting to escape, the young woman opens the front door and finds herself not outside but once again in the front hallway of this house of horrors, a nightmarish reimagining of a family home. As the door slams shut behind her, it becomes clear that there is no escape.(1) She is trapped inside the horrific dream vision that forms the narrative basis of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, the postmodern counterpart of the dream visions dating from the 14th century. Characterized by what Deanne Williams refers to as a ‘dynamic relation between text and commentary,’(2) the medieval ‘dream vision’ is defined by its allegorical orientation, an emphasis on the surreal or absurd, and a subjective and flexible reality. -

1 the Politics of Falling Juli Carson What If I Say to You Now: Do You

The Politics of Falling Juli Carson What if I say to you now: Do you remember going to the Fabulous Forum? —Daniel Joseph Martinez Mise-en-scène Try to remember something: an event, a person or a place. It’s a testament to your individual consciousness, your fundamental agency as a subject. Simply, memories are the scaffolding for our intuitive sense of self. And yet, what if this self is really nothing more than a cherished chimera? As Thomas Metzinger, a German philosopher informed by neuroscience, instructs: “Nobody ever was or had a self. All that ever existed were conscious self-models that could not be recognized as models.” From this perspective, the phenomenal self is really a process, not a thing. Moreover, this process—this self- model—is necessarily transparent. “Because you cannot recognize your self-model as a self-model . you look right through it. You don’t see it. But you see with it.”1 In reality, consciousness is thus a transparent, invisible process whereby we feel ourselves feeling ourselves, even though the means through which we do this can never be seen as such.2 Just the same, Daniel Martinez’s The Report of My Death Is an Exaggeration; Memoirs: Of Becoming Narrenschiff is an attempt to do just that: to make us collectively see our 1 self-model as a model. Accordingly, a libidinal pulse throbs through Memoirs: Of Becoming Narrenschiff—the individual self alternately falling apart and falling together— a consequence of Martinez’s journey into the urban sublime when he embarked upon his Narrenschiff, his Ship of Fools. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The English Dream Vision

The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell The English Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM By J. Stephen Russell The first-person dream-frame nar rative served as the most popular English poetic form in the later Mid dle Ages. In The English Dream Vision, Stephen Russell contends that the poetic dreams of Chaucer, Lang- land, the Pearl poet, and others employ not simply a common exter nal form but one that contains an internal, intrinsic dynamic or strategy as well. He finds the roots of this dis quieting poetic form in the skep ticism and nominalism of Augustine, Macrobius, Guillaume de Lorris, Ockham, and Guillaume de Conches, demonstrating the interdependence of art, philosophy, and science in the Middle Ages. Russell examines the dream vision's literary contexts (dreams and visions in other narratives) and its ties to medieval science in a review of medi eval teachings and beliefs about dreaming that provides a valuable survey of background and source material. He shows that Chaucer and the other dream-poets, by using the form to call all experience into ques tion rather than simply as an authen ticating device suggesting divine revelation, were able to exploit con temporary uncertainties about dreams to create tense works of art. continued on back flap "English, 'Dream Vision Unglisfi (Dream Vision ANATOMY OF A FORM J. Stephen Russell Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 1988 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. Quotations from the works of Chaucer are taken from The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. -

Individual Spirituality and the Canterbury Tales: an Analysis Of

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-18-2012 Individual Spirituality and The Canterbury Tales: An Analysis of the Philosophical Connection Between The Tale of Melibee and The Parson’s Tale as It Operates within the Narrative Framework Chelsea R. Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Chelsea R., "Individual Spirituality and The Canterbury Tales: An Analysis of the Philosophical Connection Between The Tale of Melibee and The Parson’s Tale as It Operates within the Narrative Framework" (2012). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1465. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1465 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Individual Spirituality and The Canterbury Tales: An Analysis of the Philosophical Connection Between The Tale of Melibee and The Parson’s Tale as It Operates within the Narraitive Framework A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Chelsea Martin B.A.