CHAPTER ONE: Palestine Media Watch and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to Understanding the Centuries-Old Struggle

ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to understanding the centuries-old struggle “When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. HonestReporting Defending Israel From Media Bias ANTI-SEMITISM IS THE DISSEMINATION OF FALSEHOODS ABOUT JEWS AND ISRAEL www.honestreporting.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 History Part 2 Jerusalem Part 3 Delegitimization Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Part 4 Hamas, Gaza, and the Gaza War Part 5 Why Media Matters 2 www.honestreporting.com ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to understanding the centuries-old struggle The Middle East nation we now know as the State of Israel has existed throughout history under a va riety of names: Palestine, Judah, Israel, and others. Today it is surrounded by Arab states that have purged most Jews from their borders. Israel is governed differently. It follows modern principles of a western liberal democracy and it pro vides freedom of religion. Until the recent discovery of large offshore natural gas deposits, Israel had few natural resources (including oil), but it has an entrepreneurial spirit that has helped it become a center of research and development in areas such as agriculture, computer science and medical tech nologies. All Israeli citizens have benefited from the country’s success. Yet anti-Israel attitudes have become popular in some circles. The reason ing is often related to the false belief that Israel “stole” Palestinian Arab lands and mistreated the Arab refugees. But the lands mandated by the United Nations as the State of Israel had actually been inhabited by Jews for thousands of years. -

Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2009 Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, First Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting, 1 The ourJ nal for the Study of Antisemitism (JSA) 139 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. jsa1-2_cv_jsa1-2_cv 3/1/2010 3:41 PM Page 2 Volume 1 Issue #2 Volume JOURNAL for the STUDY of ANTISEMITISM JOURNAL for the STUDY of ANTISEMITISM of the STUDY for JOURNAL Volume 1 Issue #2 2009 2009 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1564792 28003_jsa_1-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 03/01/2010 12:09:36 \\server05\productn\J\JSA\1-2\front102.txt unknown Seq: 5 26-FEB-10 9:19 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Number 2 Preface It Never Sleeps: A Note from the Editors ......................... 89 Antisemitic Incidents around the World: July-Dec. 2009, A Partial List .................................... 93 Articles Defeat, Rage, and Jew Hatred .............. Richard L. Rubenstein 95 Betraying Truth: Ethics Abuse in Middle East Reporting .......................... -

Psychology of Terrorism

Psychology of Terrorism Bruce Bongar, et al., Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PSYCHOLOGY OF TERRORISM This page intentionally left blank Psychology of Terrorism EDITED BY Bruce Bongar Lisa M. Brown Larry E. Beutler James N. Breckenridge Philip G. Zimbardo 1 2007 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright Ó 2007 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaton Data Psychology of terrorism / edited by Bruce Bongar ...[et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN–13 978–0–19–517249–2 ISBN 0–19–517249–3 1. Terrorism—Psychological aspects. 2. Disasters—Psychological aspects. 3. Victims of terrorism—Mental health. I. Bongar, Bruce Michael. [DNLM: 1. Terrorism—psychology. 2. Stress, Psychological —therapy. 3. Survivors— psychology. WA 295 P9743 2006] RC569.5.T47P83 2006 363.32019—dc22 2005034001 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper This book is dedicated to all those who fight terrorism, to all those who strive to prevent terrorism, and to all those whose lives have been irreparably scarred by terrorism. -

REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed?

The iEngage Project of The Shalom Hartman Institute Jerusalem, Israel | June 2013 REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed? Jewish journalists and the media they work for are at a crossroads. As both their audiences and the technologies they use are changing rapidly, Jewish media journalists remain committed and optimistic, yet they face challenges as great as any in the 300-year history of the Jewish press. ALAN D. ABBEY REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed? ALAN D. ABBEY The iEngage Project of the Shalom Hartman Institute http://iengage.org.il http://hartman.org.il Jerusalem, Israel June 2013 The iEngage Project of The Shalom Hartman Institute TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………........…………………..4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………….....……………………...…...6 Key Findings………………………………………………………………………………..……6 Key Recommendations………………………………………………………………………….7 HISTORY OF THE JEWISH MEDIA……………………...……………………….8 Journalists and American Jews – Demographic Comparisons………………………………….12 JEWISH IDENTITY AND RELIGIOUS PRACTICE…………………………….14 Journalism Experience and Qualifications…………………………………………………….15 HOW JOURNALISTS FOR JEWISH MEDIA VIEW AND ENGAGE WITH ISRAEL……………………………………………….16 Knowledge of Israel and Connection to Israel…………………………………………...…….18 Criticism of Israel: Is It Legitimate?………………….………….…………………………..…….19 Issues Facing Israel…………………………………………………….…………………...….21 Journalism Ethics and the Jewish Journalist………………………………………..…….22 Activism and Advocacy among Jewish Media Journalists...…….......………………….26 -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT www.HonestReporting.com We believe Israel deserves fair treatment in the news. We know public opinion is shaped by the media. We empower people to respond to anti-Israel bias. Help us ensure fair media coverage of Israel. Receive our free daily newsletter and educational materials: honestreporting.com/signup HonestReporting US Board of Directors President: Robert A. Blum Members David A. Barish, Ph.D. • Martha Barvin • Daniela Bendor • Max Blankfeld • Marc Levine Morris F. Mintz • Sharon Mishkin • Jodi Samuels • Aaron Spool • Arthur Weinstein Executive Staff Daniel Pomerantz, Chief Executive Officer International Staff Charles Bybelezer, Managing Editor • Jerry Glazer, Director of Finance and Administration Suzanne Lieberman, Director of Missions & Donor Relations • Laura Cornfield, Director of MediaCentral HonestReporting Defending Israel From Media Bias 2020 ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT www.HonestReporting.com This annual report is also available online as a downloadable PDF with additional content hyperlinks at www.honestreporting.com/2019-annual-report/ HonestReporting IN ACTION We deliver real solutions to We mobilize at a real problems moment’s notice Media bias is a global problem that affects Israel and The longer biased news is out there, the more people will Jewish communities around the world. With our be misinformed. That’s why we have a rapid response monitoring capabilities, critiques and social media mechanism. Corrections begin to appear quickly so that presence, we put news outlets on notice and hold them the public is told the truth. to account. We have leverage Our team of professionals The most valuable assets for news agencies are their makes every dollar count reputation and credibility. -

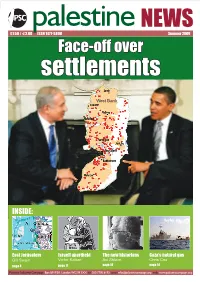

Face-Off Over Settlements

summer09 palestine NEWS 1 £1.50 / €2.00 ISSN 1477-5808 Summer 2009 Face-off over settlements West Bank INSIDE: East Jerusalem Israeli apartheid The new historians Gaza’s natural gas Gill Swain Victor Kattan Avi Shlaim Chris Cox page 4 page 11 page 14 page 18 Palestine Solidarity Campaign Box BM PSA London WC1N 3XX tel 020 7700 6192 email [email protected] web www.palestinecampaign.org 2 palestine NEWS summer09 Contents 3 Can Obama deliver? Betty Hunter examines the clash between Obama and Netanyahu over settlements 4 East Jerusalem — a stolen city Dramatic map reveals how settlements are spreading through Jerusalem 6 Q: Where are the Palestinian Ghandis? A: In Jail Bekah Wolf reports on a grassroots resistance movement — and the Israeli response 9 Trade unionists shocked and angry Kiri Tunks and Bernard Regan on a trade union delegation to the OPTs 10 BBC betrays Jeremy Bowen How the BBC Trust caved in to pressure and censured its Middle East editor Cover map: fmep_v18n1_map. pdf from the Foundation for 11 Israel guilty of colonialism and apartheid Middle East Peace. Victor Kattan on a hard-hitting South African report www.fmep.org 12 Dialogue with the Diaspora ISSN 1477 - 5808 Jeff Halper reflects on the reasons for the uproar he caused in Australia Also in this issue... 14 The ‘new history’ and the Nakba Gaza music school reopens Prof Avi Shlaim describes the impact of re-examining the past page 21 16 Operation ‘Hasbara’ Diane Langford examines how the Israeli propaganda machine manipulates the message 17 Between a rock and -

Palestinian Manipulation of the International Community

PALESTINIAN MANIPULATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Ambassador Alan Baker (ed.) Palestinian Manipulation of the International Community Edited by Amb. Alan Baker ISBN: 978-965-218-117-6 © 2014 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Contents Overview: Palestinian Manipulation of the International Community Amb. Alan Baker................................................................................................. 5 Manipulating International Law as Part of Anti-Israel “Lawfare” Prof. Robbie Sabel...............................................................................................13 Universal Jurisdiction: Learning the Costs of Political Manipulation the Hard Way Dr. Rephael Ben-Ari...........................................................................................23 The Demonization of Israel at the United Nations in Europe Mr. Hillel Neuer.................................................................................................47 The Role of NGOs in the Palestinian Political War Against Israel Prof. Gerald M. Steinberg...................................................................................65 Politicizing the International Criminal Court Prof. Eugene Kontorovich....................................................................................79 Degrading International Institutions: The United Nations Goldstone Report Amb. Dore Gold .................................................................................................91 -

Beyond Images Project

THE BEYOND IMAGES PROJECT www.beyondimages.info Israel website guide: Resources for busy advocates by Andrew White - last updated 28 August 2010 The purpose of this guide…. and how it is organised Many people wish to speak up for Israel. This guide to websites is designed to support advocacy which is coherent, well-informed, humane, pro-active and balanced. The guide is divided into the following categories (and there is some overlap between them): News, analysis and the Israeli government Gaza, Israel and Hamas – specific resources Thinktanks International law, Israel and the Middle East Advocacy tools, resources and techniques Israeli society Israel‟s medical and humanitarian contributions around the world Jewish-Arab coexistence projects in Israel Media monitoring projects on Israel Monitoring media in the Arab and Muslim world NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) How have the websites been chosen? There are many websites on Israel. Obviously, this guide is very selective. I highlight resources which focus on education and information. I do not cover the (often excellent) websites of Zionist federations, lobbying or communal organisations or party political groups, because their sites normally have a different emphasis. I have chosen to provide a diverse range of sites, which reflects the diversity of opinion in Israel itself. All listed websites are in English. Many offer multiple languages. See each site for details. Andrew White is a London-based lawyer, founder of the Israel advocacy/education project Beyond Images, and author of the Beyond Images website (www.beyondimages.info). All opinions expressed below about sites, and site selections, are Andrew‟s personal opinions. -

Soft Powerlessness: Arab Propaganda and the Erosion of Israel's International Standing

Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy Institute for Policy and Strategy Soft Powerlessness: Arab Propaganda and the Erosion of Israel's International Standing Working Paper Submitted for the Herzliya Conference, January 21-24, 2006 Emmanuel Navon This paper reflects the opinions of its author only “On résiste à l'invasion des armées, on ne résiste pas à l'invasion des idées.” Victor Hugo “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” Mark Twain 1 Table of Contents Abstract p. 3 Introduction p. 4 Part I: Defining and Understanding the War of Ideas p. 7 1. A New Type of Warfare p. 7 2. The War of Ideas Against Israel p. 15 3. Israel’s Achilles’ Heel p. 30 Part II: The War of Ideas in the International Arena p. 37 1. The United States as a Target p. 37 2. The Role of the United Nations p. 40 3. The Role of NGOs p. 46 Part III: The Problem with Europe p. 58 1. Europe’s Ideological and Cultural Surrender p. 58 2. European Hostility Toward Israel Since September 2000 p. 64 3. The Economic Boycott of Israel in Europe p. 72 Conclusion p.79 Appendix: Selected List of Pro-Israel Organizations p. 86 Bibliography p. 94 2 Abstract The present study explains why Israel is widely perceived as an international villain, argues that this negative image is detrimental to Israel’s security and economic interests, and provides practical solutions to Israel’s PR deficiencies. In the 1970s, the PLO adopted the “propaganda strategy” of the Chinese and Vietnamese Communists. -

Arab-Israeli Conflict

A GUIDE TO THE Arab-Israeli Conflict By Mitchell G. Bard American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) 2810 Blaine Dr. Chevy Chase, MD 20815 http://www.JewishVirtualLibrary.org Copyright © American Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) Inc., 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form with out the written per mission of AICE, Inc. ISBN 0-9712945-4-2 Printed in the United States of America American Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) 2810 Blaine Dr. Chevy Chase, MD 20815 Tel. 301-565-3918 Fax. 301-587-9056 Email. [email protected] http://www.JewishVirtualLibrary.org Other studies available from AICE (all are now available on our web site): ■ Partners for Change: How U.S.-Israel Cooperation Can Benefi t America ■ Learning Together: Israeli Innovations In Education That Could Benefi t Amer icans ■ Breakthrough Dividend: Israeli Innovations In Bio technology That Could Ben efi t Americans ■ Experience Counts: Innovative Programs For The Elderly In Israel That Can Benefi t Americans ■ Building Bridges: Lessons For America From Novel Israeli Approaches To Promote Coexistence ■ Good Medicine: Israeli Innovations In Health Care That Could Benefi t Amer icans ■ Rewriting History in Textbooks ■ On One Foot: A Middle East guide for the perplexed or How to respond on your way to class, when your best friend joins an anti-Israel protest ■ TENURED OR TENUOUS: Defi ning the Role of Faculty in Supporting Israel on Campus Production, new cover art and maps by North Market Street Graphics Original Book Logo Design, Cover concept, Typography, Map Illustration: Danakama / Nick Moscovitz / NYC Table of Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................................v 1. -

Charity Navigator

HonestReporting Defending Israel From Media Bias 2014 ANNUAL REPORT www.honestreporting.com HonestReporting is a global community fghting for fair media coverage of Israel. CONTENTS 4 International Outreach 6 United States Outreach 8 Engaging Radio, Video, and Social Media 10 The Blankfeld Award for HonestReporting Board of Directors Media Critique President of the Board: David A. Barish, Ph.D. 11 Fighting BDS Members of the Board 12 Holding the Media to Account 14 Operation Protective Edge Executive Staf 16 Getting the Corrections 17 HR in the Media 18 HR Missions to Israel International Staf 19 Guest Lecturers 20 MediaCentral 22 Financial Report This publication contains underlined hyperlinks. Clicking them from this PDF will open a related web page. The Table of Contents above is linked to interior pages. A Message from our President Dear Friends, A Message from our CEO Dear Friends, ONE DAY: Global scope of the Israel Daily News Stream email 48,117 OPENS 22,036 CLICKS International Outreach HR Managing Editor Simon Plosker spoke to against Israel. The visit was part of a two-day a group from the Onward Israel program of Student Activism seminar run by Neil Lazarus Australian and South African students. of Awesome Seminars. The seminar includes Simon was also on an Israel advocacy panel sessions on various elements in advocacy as part of a two-day “Next Israel” seminar training so that the students are equipped to organized by the IDC Herzliya’s student defend Israel when they return to the U.S. union in response to anti-Israel activities Thirty participants of the Israel Government on campuses worldwide. -

Mediadevelopmentvol. XLX 3/2002

Media Development Vol. XLX 3/2002 Published four times a year by the World 23 International media coverage Association for Christian Communication 357 Kennington Lane and changing societies: London SE11 5QY England The view from Canada Telephone +44 (0)20 7582 9139 Fax +44 (0)20 7735 0340 Haroon Siddiqui E-mail: [email protected] http://www.wacc.org.uk 26 What constitutes full and fair media coverage of Israeli-Palestinian issues? Editors Pradip N. Thomas Marda Dunsky Philip Lee 10 US media turn a blind eye to the Israeli occupation Editorial consultants Sarah Eltantawi Clifford G. Christians, Professor, University of Illinois, Urbana, USA. Marlene Cuthbert, Professor Emeritus, University of 14 Sharo n ’s cunning plan Windsor, Ontario, Canada Regina Festa, Director, Workers’ Television, James M. Wall São Paulo, Brazil. Cees J. Hamelink, Professor, University of Amsterdam, 16 J o u rnalists’ Code of Fair Practice Amsterdam, Netherlands. Karol Jakubowicz, Lecturer, Institute of Journalism, Warsaw, Poland. 17 Style-sheet on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict Kong Zhiqiang, Professor, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. J. Martin Bailey Fernando Reyes Matta, Director, Instituto Latinoamericano de Estudios Transnacionales, 32 On the screen . Santiago, Chile. Michèle Mattelart, Professor, University of Paris, France. Emile G. McAnany, Professor, University of Texas, 36 In the event . Austin, USA. Breda Pavli˘c, Unesco, Paris. Usha V. Reddi, Professor, Osmania University, 39 Theological and ethical issues in Hyderabad, India. Robert A. White, Director, Centro v i rtual communication Interdisciplinare sulla Comunicazione Sociale, Isabelle Graesslé Gregorian University, Rome, Italy. 44 A n d rei Tarkovsky: Cinema’s poet Subscriptions Individual subscribers world-wide £20 or US$ 30.