Project Renewal : an Introduction to the Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

March 16, 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before

ICC-01/18-79 16-03-2020 1/32 NM PT Original: English Case: ICC-01/18 Date: March 16, 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Péter Kovács, Presiding Judge Judge Marc Perrin de Brichambaut Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou SITUATION IN THE STATE OF PALESTINE Public Written Observation of Shurat HaDin on the Issue of Affected Communities Source: SHURAT HADIN – Israel Law Center Israel, 10 HaTa'as Street Ramat Gan, 52512. Phone: 972-3-7514175 Fax: 972-3-7514174 Email: [email protected] 1/32 Case: ICC-01/18 ICC-01/18-79 16-03-2020 2/32 NM PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Fatou Bensouda James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence Paolina Messida Xavier-Jean Keita States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae The competent authorities of 'palestine' All Amici Curiae The competent authorities of The State of Israel REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Peter Lewis Detention Section Victims and Witnesses Unit Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Philip Ambach Case: ICC-01/18 2/32 ICC-01/18-79 16-03-2020 3/32 NM PT 1. Consistent with the Pre-Trial Chamber's order of Feb 20, 20201, granting leave to submit observations, and in accordance with Rule 103 to the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, Shurat HaDin – Israel Law Center (SHD) respectfully submits its written observation in respect of the issue of jurisdiction in the case regarding “The State of Palestine”. -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth

Diaspora and Zionism in Jewish American Literature Brandeis Series in American Jewish History,Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Leon A. Jick, The Americanization of the Synagogue, – Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor, Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction Gerald Tulchinsky, Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community Shalom Goldman, editor, Hebrew and the Bible in America: The First Two Centuries Marshall Sklare, Observing America’s Jews Reena Sigman Friedman, These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, – Alan Silverstein, Alternatives to Assimilation: The Response of Reform Judaism to American Culture, – Jack Wertheimer, editor, The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed Sylvia Barack Fishman, A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community Diane Matza, editor, Sephardic-American Voices: Two Hundred Years of a Literary Legacy Joyce Antler, editor, Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture Jack Wertheimer, A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America Beth S. Wenger and Jeffrey Shandler, editors, Encounters with the “Holy Land”: Place, Past and Future in American Jewish Culture David Kaufman, Shul with a Pool: The “Synagogue-Center” in American Jewish History Roberta Rosenberg Farber and Chaim I. Waxman,editors, Jews in America: A Contemporary Reader Murray Friedman and Albert D. Chernin, editors, A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews Stephen J. Whitfield, In Search of American Jewish Culture Naomi W.Cohen, Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership Barbara Kessel, Suddenly Jewish: Jews Raised as Gentiles Jonathan N. Barron and Eric Murphy Selinger, editors, Jewish American Poetry: Poems, Commentary, and Reflections Steven T.Rosenthal, Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the American Jewish Love Affair with Israel Pamela S. -

Forgotten Palestinians

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 THE FORGOTTEN PALESTINIANS 10 1 2 3 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 THE FORGOTTEN 6 PALESTINIANS 7 8 A History of the Palestinians in Israel 9 10 1 2 3 Ilan Pappé 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 5 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 36x 1 In memory of the thirteen Palestinian citizens who were shot dead by the 2 Israeli police in October 2000 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2011 Ilan Pappé 6 The right of Ilan Pappé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by 7 him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 8 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright 9 Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from 20 the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, 2 please contact: U.S. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Zionism and Diaspora in AM Klein's Journalism

Document generated on 10/01/2021 6:30 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Exile beyond Return Zionism and Diaspora in A.M. Klein’s Journalism Emily Ballantyne Volume 40, Number 2, 2015 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl40_2art09 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Ballantyne, E. (2015). Exile beyond Return: Zionism and Diaspora in A.M. Klein’s Journalism. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 40(2), 164–188. All rights reserved, © 2015 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Exile beyond Return: Zionism and Diaspora in A.M. Klein’s Journalism Emily Ballantyne oet, lawyer, and journalist A.M. Klein (1902-72) has been well celebrated for his considerable contributions to Jewish Montreal and Canada more broadly. Thanks to the publication Pof his letters in 2011, edited by Elizabeth Popham, the fascinating and complex role played by his non-fiction writing must be reconsidered in light of what she so aptly describes in scare quotes as his “public rela- tions work” (“Introduction” xiii), his dual role as editor of the Canadian Jewish Chronicle and speechwriter/fundraiser for the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC). -

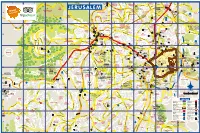

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E . -

Israel 2019 Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are due to representatives of government ministries and agencies as well as many others from a variety of organizations, for their essential contributions to each chapter of this book. Many of these bodies are specifically cited within the relevant parts of this report. The inter-ministerial task force under the guidance of Ambassador Yacov Hadas-Handelsman, Israel’s Special Envoy for Sustainability and Climate Change of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Galit Cohen, Senior Deputy Director General for Planning, Policy and Strategy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, provided invaluable input and support throughout the process. Special thanks are due to Tzruya Calvão Chebach of Mentes Visíveis, Beth-Eden Kite of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amit Yagur-Kroll of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Ayelet Rosen of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Shoshana Gabbay for compiling and editing this report and to Ziv Rotshtein of the Ministry of Environmental Protection for editorial assistance. 3 FOREWORD The international community is at a crossroads of countries. Moreover, our experience in overcoming historical proportions. The world is experiencing resource scarcity is becoming more relevant to an extreme challenges, not only climate change, but ever-increasing circle of climate change affected many social and economic upheavals to which only areas of the world. Our cooperation with countries ambitious and concerted efforts by all countries worldwide is given broad expression in our VNR, can provide appropriate responses. The vision is much of it carried out by Israel’s International clear. -

Inquiries Into Economies of Violence in Israel/Palestine

INQUIRIES INTO ECONOMIES OF VIOLENCE IN ISRAEL/PALESTINE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 2016 By François-Xavier Plasse-Couture Dissertation committee 1. Michael J. Shapiro, chairperson 2. Kathy Ferguson 3. Jairus Grove 4. Samson Okoth Opondo 5. Laura Lyons Keywords: Israel, Palestine, violence, race, settler colonialism, biopolitics To Anouk, Romy, Mimi, and Laurence, generous, intelligent, unique and loving women who thought me the most and have always been with me, even in difficult times. You are my inspiration. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for the financial support that made this research possible. Additionally, I want to thank my supervisor and true friend Michael J. Shapiro for his patience, dedication, generosity, support, numerous and precious advices, his friendship, for nurturing such a young and inspiring scholarly open mind and be such a great inspiration. I am grateful to Samson Opondo for his time and generosity, for his wise comments, suggestions, discussions and encouragements on the various projects’ steps, from the proposal to the submission. I am thankful to Jairus Grove, Kathy Ferguson, and Laura Lyons for their useful and constructive comments on the various steps that lead to completion of this dissertation. I am also indebted to Philippe Beaulieu-Brossard, Samuel Vaillancourt, Joan Deas, David Grondin, Ben Schrader, Breanne Gallagher, Katie Brennan, Sharain Naylor, Rex Troumbley, Julia Guimaraes, Akta Kaushal, Noah Viernes, Nicole Grove, John Sweeney, Simon Hogue, Tani Sebro, Jimmy Weir, Yair Geva, Shiri Hornik, Amit Friedman, Avner Peled for their friendship, support, useful comments, suggestions, and generous help at various stages of the project be it during a seminar, a conference, or around a pint. -

ALIYAH to ISRAEL in the 1990S Lessons for the Future PROF

ALIYAH TO ISRAEL IN THE 1990s Lessons for the Future PROF. JACK HABIB Director, JCD-Broolcdale Institute, Jerusalem and JUDITH KING Director of Researcli on Immigrant Absorption, JDC-Broolcdale Institute, Jerusalem Almost a million immigrants made aliyah to Israel during the 1990s. To meet this massive immigration, Israeli adopted new immigration policies that differed significantly from previous ones. The professional community and Diaspora Jewry played leading roles in introducing programmatic and policy changes and innovations. he decade of the 1990s was a dramatic STRATEGIES AND KEYS TO SUCCESS Tepisode in the history of aliyah to the state of Israel. In this brief article, we discuss The strategies adopted by Israel to meet the nature of the challenge, the strategies the challenge posed by the sheer magnitude adopted, the Diaspora-Israeli partnership, of the immigration represented significant some of the achievements, and remaining departures from previous policies. The pro challenges. We conclude with some general fessional community played a leading role in lessons from this experience. identifying the need for change and assisting Israeli society to adopt its strategies to this unique challenge. NATURE OF THE CHALLENGE One of the most significant changes was the shift from the initial absorption of immi In the 1990s, 956,000 immigrants came to grants in absorption centers to their direct Israel. Of these, 824,000 were from the FSU integration into the community through their and 40,000 from Ethiopia. Immigrants thus rental or purchase of apartments on the open represented 14 percent of the Israeli popula market with government financial assistance. tion at the end of the decade.