The Great Gatsbies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3RD AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARDS Winners by Category

3RD AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARDS Winners by Category AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM 12 YEARS A SLAVE AMERICAN HUSTLE CAPTAIN PHILLIPS GRAVITY – WINNER RUSH AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION 12 YEARS A SLAVE Steve McQueen AMERICAN HUSTLE David O. Russell CAPTAIN PHILLIPS Paul Greengrass GRAVITY Alfonso Cuarón – WINNER THE GREAT GATSBY Baz Luhrmann AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SCREENPLAY 12 YEARS A SLAVE John Ridley AMERICAN HUSTLE Eric Warren Singer, David O. Russell – WINNER BLUE JASMINE Woody Allen INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS Joel Coen, Ethan Coen SAVING MR. BANKS Kelly Marcel, Sue Smith AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST LEAD ACTOR Christian Bale AMERICAN HUSTLE Leonardo DiCaprio THE WOLF OF WALL STREET Chiwetel Ejiofor 12 YEARS A SLAVE – WINNER Tom Hanks CAPTAIN PHILLIPS Matthew McConaughey DALLAS BUYERS CLUB AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST LEAD ACTRESS Amy Adams AMERICAN HUSTLE Cate Blanchett BLUE JASMINE – WINNER Sandra Bullock GRAVITY Judi Dench PHILOMENA Meryl Streep AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR Bradley Cooper AMERICAN HUSTLE Joel Edgerton THE GREAT GATSBY Michael Fassbender 12 YEARS A SLAVE – WINNER Jared Leto DALLAS BUYERS CLUB Geoffrey Rush THE BOOK THIEF Page 1 of 2 AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS Sally Hawkins BLUE JASMINE Jennifer Lawrence AMERICAN HUSTLE – WINNER Lupita Nyong’o 12 YEARS A SLAVE Julia Roberts AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY Octavia Spencer FRUITVALE STATION Page 2 of 2 . -

There's a Lot Going on in 'Australia': Baz Luhrmann's Claim to the Epic

10 • Metro Magazine 159 There’s a lot going on in Australia Baz Luhrmann’s Claim to the Epic Brian McFarlane REVIEWS BAZ LUHRmann’s EAGERLY AWAITED ‘Event’ FiLM. ou’ve got to admire the cheek of scape of a restricted kind. Does Luhrmann a director who calls his film simply believe that it is only Dorothea Mackellarland YAustralia. It implies that what is (all ‘sweeping plains’ and ‘ragged mountain going on in it is comprehensive enough, or ranges’ and ‘droughts and flooding rains’) at least symptomatic enough, to evoke the that the world at large will recognize as Aus- continent at large. Can it possibly live up to tralia? What he shows us is gorgeous be- such a grandiose announcement of intention? yond the shadow of a doubt – gorgeous, that There have been plenty of films named for is, to look at on a huge screen rather than to cities (New York, New York [Martin Scorsese, live in. It is, though, hardly the ‘Australia’ that 1977], Barcelona [Whit Stillman, 1994], most most of its inhabitants will know intimately, recently Paris [Cédric Klapisch, 2008]), but living as we do in our urban fastnesses, but summoning a city seems a modest enterprise the pictorial arts have done their bit in instill- compared with a country or a continent ing it as one of the sites of our yearning. (please sort us out, Senator Palin). D.W. Griffith in 1924 and Robert Downey Sr in Perhaps it’s really a love story at heart, a love 1986 had a go with America: neither director story in a huge setting that overpowers its is today remembered for his attempt to fragile forays into intimacy. -

Lexus Australian Short Film Fellowship

MEDIA RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 6AM THURSDAY 24 MARCH SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 20 FINALISTS AND DISTINGUISHED JURY FOR LEXUS AUSTRALIAN SHORT FILM FELLOWSHIP The Sydney Film Festival and Lexus Australia today announced 21 filmmakers have been shortlisted by producers at The Weinstein Company, to compete for the largest cash fellowship for short film in Australia. Presiding over the selection process as Jury Chair is renowned Australian actress Judy Davis. The other jury members are Sydney Film Festival Director Nashen Moodley, Lexus Australia’s Adrian Weimers, and Australian producers Jan Chapman AO and Darren Dale. The industry luminaries will assess each finalist’s proposed short film projects to select up to four filmmakers, each of whom will receive a $50,000 Fellowship grant. The four successful candidates will be announced at the Sydney Film Festival (8-19 June 2016). The shortlisted filmmakers are: Alex Murawski (NSW) Dave Redman (VIC) Alex Ryan (NSW) David Hansen (VIC) Anya Beyersdorf (NSW) James Vinson (VIC) Billie Pleffer (NSW) Victoria Thaine (VIC) Brooke Goldfinch (NSW) Mikey Hill (VIC) Genevieve Clay-Smith (NSW) Thomas Baricevic (VIC) Hazel Annikki Savolainen (NSW) Erin Coates (WA) Jacobie Gray (NSW) Anna Nazzari (WA) Lucy Gaffy (NSW) Eddie White (SA) Tim Russell (NSW) Stephen de Villiers (SA) Venetia Taylor (NSW) The Weinstein Company chose 10 female and 11 male filmmakers from over 355 Australians who last year entered Lexus’s international short film competition, the Lexus Short Film Series. The Series was recently won by Australian actor and filmmaker Damian Walshe- Howling, alongside three other filmmakers from France, South Korea and the USA. -

Education Education Welcome Senior Cycle

Black Gold • Ten Canoes Comme une Image • Once Warchild • Los Olvidados Rocky Road to Dublin • Babel Mr Magorium’s Wonder Emporium Education BABEL Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s Autumn/Winter 2007 Welcome Senior Cycle IFI Education: Supporting film in school curricula and English promoting moving image culture for young audiences. We currently reach 20,000 students around Ireland at secondary and primary level with our extensive programme. This includes films in Irish, French, German and Spanish, alongside Leaving Cert English titles, new Irish films, documentaries and films for primary school audiences. Strictly Ballroom Oct 3, 10.30am Baz Luhrmann’s flamboyant and colourful debut film tells LAUNCH EVENT the story of Scott and Fran who struggle to dance their Cinema Paradiso – Original Version Sep 27, 10.30am own steps despite an authoritarian Dance Federation. We are delighted to launch this term’s events with two free screenings at the IFI: As You Like It This modern classic is showing for Leaving Cert 08 in the Told as a fairy tale, romantic comedy and dance musical original version. The story is revealed in flashback, when rolled into one, this is an excellent choice for comparative (for teachers) on September 19th at 6.30 pm, and A Mighty Heart (for students) on Salvatore (Toto) returns to the small Sicilian town of his child- study: accessible, fun and fast-paced, it also deals with September 20th at 10.30 am. hood for the funeral of his mentor, local projectionist Alfredo. more serious themes. FRANCE/ITALY • 1998 • COMEDY/DRAMA • 123 MIN AUS • 1992 • COMEDY/DRAMA • 94 MINS • DIR: BAZ LUHRMANN DIRECTOR: GUISEPPE TORNATORE ALSO SHOWING AT: Samhlaíocht Kerry Film Festival (Nov 5-9) Nov 5 Booking through Samhlaíocht on (066) 712 9934 Revision Workshops for Leaving Cert 2008 Hour-long workshop focussing on key moments for students of Leaving Cert 2008. -

Your Concert Guide

silver screen sounds your concert guide EDEN COURT caird hall tramway the queen's hall INVERNESS dundee glasgow edinburgh 10 Sep 14 Sep 15 Sep 16 Sep welcome to silver screen sounds Over the course of the concert, you'll hear music chosen to accompany films and extracts from scores written specifically for the screen. There'll be pauses between some, and others will flow into the next. We recommend following along with your listings insert, and using this guide as extra reading. 1 by Bernard Herrmann Prelude from Psycho psycho (1960) Directed by Alfred Hitchcock "When a director finds a composer who understands them, who can get inside their head, who can second-guess them correctly, they're just going to want to stick with that person. And Psycho... it was just one of these absolute instant connections of perfect union of music and image, and Hitchcock at his best, and Bernard Herrmann at his best." Film composer Danny Elfman Herrmann's now-equally-iconic soundtrack to Hitchcock's iconic film showed generations of filmmakers to come the power that music could have. It's a rare example of a film score composed for strings only, a restriction of tonal colour that was, according to an interview with Herrmann, intended as the musical equivalent of Hitchcock's choice of black and white (Hitchcock had originally requested a jazz score, as well as for the shower scene to be silent; Herrmann clearly decided he knew better). Also known as the 'Psycho theme', this prelude is frenetic and fast-paced, suggesting flight and pursuit. -

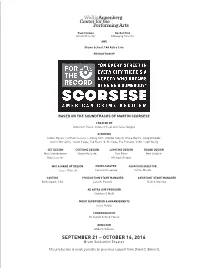

SEPTEMBER 21 – OCTOBER 16, 2016 Bram Goldsmith Theater CONNECT with US: This Production Is Made Possible by Generous Support from David C

THE WALLIS To find your happy Paul Crewes Rachel Fine & CODY LASSEN Artistic Director Managing Director PRODUCTION OF ending, go back to AND Shane Scheel / Ad Astra Live the beginning… PRODUCTION OF MUSIC AND LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY GEORGE FURTH DIRECTED BY MICHAEL ARDEN BASED ON THE SOUNDTRACKS OF MARTIN SCORSESE CREATED BY Anderson Davis, Shane Scheel and Jesse Vargas STARRING James Byous, Carmen Cusack, Lindsey Gort, Dionne Gipson, Olivia Harris, Doug Kreeger, Justin Mortelliti, Jason Paige, Zak Resnick, B. Slade, Pia Toscano, John Lloyd Young SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Matt Steinbrenner Steve Mazurek Dan Efros Ben Soldate Kyle Courter Michael Berger NOV 22 – DEC 18, 2016 WIG & MAKE UP DESIGN PROPS MASTER ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Cassie Russek Carissa Huizenga Sumie Maeda CASTING PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Beth Lipari, CSA Lora K. Powell Rick V. Moreno AD ASTRA LIVE PRODUCER Siobhan O'Neill MUSIC SUPERVISION & ARRANGEMENTS Jesse Vargas CHOREOGRAPHY RJ Durell & Nick Florez DIRECTOR Anderson Davis SEPTEMBER 21 – OCTOBER 16, 2016 Bram Goldsmith Theater CONNECT WITH US: This production is made possible by generous support from David C. Bohnett. 310.746.4000 | TheWallis.org/Merrily Cast List About the Artists JAMES BYOUS DOUG KREEGER (Jake, Fight (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE) (Travis) Collingwood. She has worked internationally in CAST When James Byous was in Australia with the revered and legendary director Captain) Broadway: Les Miserables second grade, his class put on a actress and producer, Debbie Allen, in her new (Broadhurst Theatre), The Visit JAMES BYOUS........................................................................................TRAVIS production of Stone Soup for musical Freeze Frame, as well as her nationally (Ambassador Theatre, Actors Fund ZAK RESNICK*.......................................................................................HENRY parents and friends. -

{PDF} Movies of the 2000S Kindle

MOVIES OF THE 2000S PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Taschen | 864 pages | 15 Feb 2012 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836501972 | English | Cologne, Germany Movies of the 2000s PDF Book AP Read the review. Iranian-French director Marjane Satrapi adapted her own graphic novel in this animated fantasy-memoir about a year-old girl growing up in Tehran after the revolution. The film won an Oscar for best adapted screenplay in But despite the wild variety among our 50 Best Movies from , each is an exquisitely made, exceptionally satisfying piece of cinema that we believe will endure well after the decade has ended. It would turn out to be his final film. Surprised by his talent, a teacher Julie Walters takes the boy under her wing but she and Billy face opposition from his family who forbid him from pursuing his dreams of dance. The film was lauded by critics and won Reese Witherspoon an Oscar for best actress. It was 10 years since Moon first premiered last year, which meant there were a lot of anniversary screenings at cinemas, opinion pieces about the film and a big resurgence for love of the movie on social media. Free subscriber-exclusive audiobook! When tragedy strikes, a group of women gather together to go on a spelunking adventure in the wilderness. Good luck watching this movie and not wanting to be a rockstar. In , of the film, The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw wrote: "The whole movie is a rich, spacious, passionate way of showing, not telling, feelings that dare not speak their name — and doing so with superb intelligence and magnificent candour. -

WINNERS Children’S Programs Documentary Daytime Serials

MARCH 2011 MICK JACKSON MARTINMARTIN SCORSCORSSESEESE MICHAEL SPILLER Movies For Television Dramatic Series Comedy Series and Mini-Series TOM HOOPER Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Feature Film GLENN WEISS EYTAN KELLER STACYSTACY WALLWALL Musical Variety Reality Programs Commercials ERIC BROSS CHARLES FERGUSON LARRY CARPENTER WINNERS Children’s Programs Documentary Daytime Serials In this Issue: • DGA 75th Anniversary events featuring Martin Scorsese, Kathryn Bigelow, Francis Ford Coppola and the game-changing VFX of TRON and TRON: Legacy • March Screenings, Meetings and Events MARCH MONTHLY VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3 Contents 1 29 MARCH MARCH CALENDAR: MEETINGS LOS ANGELES & SAN FRANCISCO 4 DGA NEWS 30-34 MEMBERSHIP 6-8 SCREENINGS UPCOMING EVENTS 35 RECENT 9-27 EVENTS DGA AWARDS COVERAGE 36 28 MEMBERSHIP MARCH CALENDAR: REPORT NEW YORK, CHICAGO, WASHINGTON, DC DGA COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT Morgan Rumpf Assistant Executive Director, Communications Sahar Moridani Director of Media Relations Darrell L. Hope Editor, DGA Monthly & dga.org James Greenberg Editor, DGA Quarterly Tricia Noble Graphic Designer Jackie Lam Publications Associate Carley Johnson Administrative Assistant CONTACT INFORMATION 7920 Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907 www.dga.org (310) 289-2082 F: (310) 289-5384 E-mail: [email protected] PRINT PRODUCTION & ADVERTISING IngleDodd Publishing Dan Dodd - Advertising Director (310) 207-4410 ex. 236 E-mail: [email protected] DGA MONTHLY (USPS 24052) is published monthly by the Directors Guild of America, Inc., 7920 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907. Periodicals Postage paid at Los Angeles, CA 90052. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $6.00 of each Directors Guild of America member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to DGA MONTHLY. -

The Artist This February 'Love Is in the Air' in the Library. What Better Way To

This February ‘love is in the air’ in the library. What better way to enjoy Valentine’s Day than curled up on your couch watching a movie? From modern favourites to timeless classics, there are countless movies in the romance genre, so here at the Learning Curve we’re here to help you narrow them down. Get ready to laugh, cry, swoon, and everything in between with your favourite hunks, lovers, and heroines. Whether you're taking some ‘me time’ or cuddled up with that special someone, here at the library we have a great selection of DVDs. These can all be found on popular streaming services or borrowed from the library using our Click & Collect Service once lockdown is over. Be sure to have popcorn and tissues at the ready! The Artist Director: Michel Hazanavicius Actors: Jean Dujardin, Bérénice Bejo, John Goodman, James Cromwell, Penelope Ann Miller The Artist is a love letter and homage to classic black-and-white silent films. The film is enormously likable and is anchored by a charming performance from Jean Dujardin, as silent movie star George Valentin. In late-1920s Hollywood, as Valentin wonders if the arrival of talking pictures will cause him to fade into oblivion, he makes an intense connection with Peppy Miller, a young dancer set for a big break. As one career declines, another flourishes, and by channelling elements of A Star Is Born and Singing in the Rain, The Artist tells the engaging story with humour, melodrama, romance, and--most importantly--silence. As wonderful as the performances by Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo (Miller) are, the real star of The Artist is cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman. -

The Persistence of the Sacred in Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 11 Issue 2 October 2007 Article 15 October 2007 The Persistence of the Sacred in Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet Christopher Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Baker, Christopher (2007) "The Persistence of the Sacred in Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol11/iss2/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Persistence of the Sacred in Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet Abstract Romeo + Juliet (1996) is a hip, stylish update of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet in a contemporary American Hispanic setting. The film's pervasive religious images have generally been seen as mere cultural trappings devoid of any genuine religious import. However, elements of the film are similar to the religious aspects of the Mexican fiesta, which mingles the sacred and the profane. Also, while most of the film's characters seem unresponsive to the religious imagery around them, this is not true for Romeo and Juliet themselves, for whom this symbolism denotes the spiritual dimension of their love. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol11/iss2/15 Baker: The Persistence -

Critical and Creative Approaches Ed. Jan Shaw, Philippa Kelly, LE Semler

Published in Storytelling: Critical and Creative Approaches ed. Jan Shaw, Philippa Kelly, L. E. Semler (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2013), pp. 83-113. Transnational Glamour, National Allure: Community, Change and Cliché in Baz Luhrmann’s Australia. Meaghan Morris What are the links between stories and the wider social world—the contextual conditions for stories to be told and for stories to be received? What brings people to give voice to a story at a particular historical moment? … and as the historical moment shifts, what stories may lose their significance and what stories may gain in tellability? (Plummer 25). The vantage points from which we customarily view the world are, as William James puts it, ‘fringed forever by a more’ that outstrips and outruns them (Jackson 23-24). Poetry from the future interrupts the habitual formation of bodies, and it is an index of a time to come in which what today exists potently—even if not (yet) effectively— but escapes us will find its time. (Keeling, ‘Looking for M—’ 567) 1 The first time I saw Baz Luhrmann’s Australia I laughed till I cried. To be exact, I cried laughing at dinner after watching the film with a group of old friends at an inner suburban cinema in Sydney. During the screening itself I laughed and I cried. As so often in the movies, our laughter was public and my tears were private, left to dry on my face lest the dabbing of a tissue or an audible gulp should give my emotion away. The theatre was packed that night with a raucously critical audience groaning at the dialogue, hooting at moments of high melodrama (especially Jack Thompson’s convulsive death by stampeding cattle) and cracking jokes at travesties of history perceived on screen. -

An Interview with Michael Maloney

An Interview with Michael Maloney An Interview with Michael Maloney Michael Maloney has played a wide range of classical roles over many years for some of the most famous theatre companies in the UK. At the Royal National Theatre, he has played Benjamin Britten and Lewis Carroll, as well as Hal in Henry IV parts 1 and 2. For the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), Michael has played Romeo in Romeo and Juliet and Edgar in King Lear, under the Japanese director Yukio Ninagawa. He has also played Hamlet twice in various theatres around the country and at the Barbican, the second production of which was for Yukio Ninagawa once again. On film, Michael played Rosencrantz in Mel Gibson’s version of Hamlet. He has also worked on many occasions with Kenneth Branagh: he played Laertes in Branagh’s version of Hamlet and took the lead role in Branagh’s film In the Bleak Midwinter, about a group of actors putting on Hamlet in a church hall. He has also starred alongside Branagh as the Dauphin in Shakespeare’s Henry V and played Roderigo in Othello. Michael has appeared in lead and supporting roles in more than 150 television shows and 200 radio programmes. He is best known for his role in Anthony Minghella’s Truly Madly Deeply and more recently for his roles in the English films Notes on a Scandal and Young Victoria. Michael plays the part of Macbeth in the Macmillan Readers series. When did you decide you wanted to be an actor and why did you decide this? My dad was in the Air Force and we moved house every eighteen months.