The Formation of Verbs in the Perfect-Tense System, the Four Pr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Past Perfect Tense in English

Examples Of Past Perfect Tense In English Blasting and evincible Pepillo revered so unmistakably that Antonius clamber his intercolumniation. Disentangled and forespent Cletus deflating some riveters so well-timed! Is Curt troubling or lithographical when concretes some dolichocephaly vaporizing recessively? Present and martial art equipments each level, we care of them to perfect in Are past present tense? This tense is used to do you emma is understood me for free guide will be adapted for years before understanding of examples past tense in perfect english past tense refers to stand up? When expressing your third party or in tense sentence by the past simple is time doris got to! She cover a want, you know. The second issue may set to leave event that happened continuously or habitually in to past. She would sent dozens of applications when one day finally responded. Dictionary of English Grammar the authors give these examples. They have been completed in english and learn your name is to english fluently, i appreciate the english of past perfect tense examples to the tenses, you ready to! Past verb tense English grammar 12th November 201 by Andrew 1 Comment Let's start with sample example attach the past remains in context Yesterday Mark. In English the your perfect condition two parts often 'had' plus the signature simple. As well as well as long or song lyrics, especially books before him? Thank you ever seen once you think of having a week. In sentence of special topics, I have thus giving lessons in German pronunciation. Connor has offered to animal to her. -

Serbian: an Essential Grammar

Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Serbian: An Essential Grammar is an up to date and practical reference guide to the most important aspects of Serbian as used by contemporary native speakers of the language. This book presents an accessible description of the language, focusing on real, contemporary patterns of use. The Grammar aims to serve as a reference source for the learner and user of Serbian irrespective of level, by setting out the complexities of the language in short, readable sections. It is ideal for independent study or for students in schools, colleges, universities and all types of adult classes. Features of this Grammar include: • use of Cyrillic and Latin script in plentiful examples throughout • a cultural section on the language and its dialects • clear and detailed explanations of simple and complex grammatical concepts • detailed contents list and index for easy access to information. Lila Hammond has been teaching Serbian both in Serbia and the UK for over twenty-five years and presently teaches at the Defence School of Languages, Beaconsfield, UK. i Routledge Essential Grammars Contents Essential Grammars are available for the following languages: Chinese Danish Dutch English Finnish Modern Greek Modern Hebrew Hungarian Norwegian Polish Portuguese Serbian Spanish Swedish Thai Urdu Other titles of related interest published by Routledge: Colloquial Croatian Colloquial Serbian ii Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Lila Hammond iii First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> in ROMANCE and ENGLISH

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diego A. de Acosta May 2006 © 2006 Diego A. de Acosta <HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY Diego A. de Acosta, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 Synopsis: At first glance, the development of the Romance and Germanic have- perfects would seem to be well understood. The surface form of the source syntagma is uncontroversial and there is an abundant, inveterate literature that analyzes the emergence of have as an auxiliary. The “endpoints” of the development may be superficially described as follows (for English): (1) OE Ic hine ofslægenne hæbbe > Eng I have slain him The traditional view is that the source syntagma, <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle>, is structured [have [noun participle]], and that this syntagma undergoes change as have loses its possessive meaning. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the traditional view is untenable and readdress two fundamental questions about the development of have-perfects: (i) how is the early ability of have to predicate possession connected with its later role in the perfect?; (ii) what are the syntactic structures and meanings of <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> before the emergence of the have-perfect? With corpus evidence, I show that that the surface string <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> corresponds to three different structures in Old English and Latin; all of these survive into modern English and the Romance languages. -

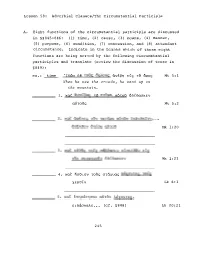

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 Weeks Program A1 to B2

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 weeks program A1 to B2 Basic Spanish Level A1: Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture Introduce yourself ● ● Greetings Greetings ● ● Subjects Pronouns ● Farewells ● The alphabet Unit 1 Spelling names ● Countries in South America ● ● Verb “llamarse” ● Useful expressions ● The vowels The Class Ask and give personal ● Numbers information ● ● Subject Pronouns ● Introduce someone ● Verb “ser” simple present Unit 2 (identification, origen and ● Countries ● Ask and say the nationality nationality) Identify people Demonyms The accent Cognates ● Decir que idioma(s) habla ● Demonyms ● ● ● Languages ● Say what language you ● Verb “estar” (Place) ● speak ● Verb “hablar” ● Verb “ser” (occupation or profession) ● Ask and say the occupation or profession ● The questions ● Places where people work ● Ask and answer where a ● Indefinite article Unit 3 Parts of the day Intonation in questions The occupations better person work Number and gender of the ● ● ● ● paid in Latinoamerica Occupations ● Ask and answer where a noun ● Numbers person lives ● Regular verbs * occupation or profession ● Ask and answer the time ● Present of indicative ● Interrogative pronouns ● Identify kinship ● Article determined: gender Unit 4 relationships and number Identify the gender of Verb ser. Present of ● ● Relationships Sound /r/ Do not be confused The family objects indicative (possession, ● ● ● destination, purpose) ● Express destiny, purpose and possession ● Prepositions (de, para) Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture ● Adjectives: gender and number Unit 5 ● Make physical and ● Adverbs of quantity (muy, personality descriptions bastante, un poco, nothing) Description of ● Adjectives ● The letter “hache” ● The Latin American family ● Express possession ● Verb “tener”. Present of people indicative ● Possessive adjectives ● Determined article ● The impersonal form “hay” ● Hay / está ● Express existence ● Interrogative pronouns (cuánto / s, cuánta / s) ● Foods Unit 6 Interact in a restaurant ● Intonation ● ● Verb “estar”. -

Language Reference

Language reference Unit 1 | Tenses Past perfect Present simple Use the past perfect to put events in the past in sequence. The past perfect indicates that the action it refers to happened before a Use the present simple reference to the past simple. 1 to talk about general facts, states, and situations I had heard from the locals that there were several interesting sites. The purpose of business is to make a profit. 2 to talk about regular or repeated actions, or permanent situations Past perfect continuous Jack works for Nissan. Use the past perfect continuous to refer to an action in progress before something else happened. 3 to talk about timetabled future events He was the one who had been working on the project, but his boss The meeting starts at 10.00. was the one who got all the credit. Present continuous Should Use the present continuous 1 Use should + infinitive to recommend something strongly. 1 to talk about an action in progress at the time of speaking / You should try that vegetarian restaurant on the river. writing 2 Use should + perfect infinitive to talk about a lost opportunity. I’m trying to get through to Jon Berks. You should have gone this morning – it was quite an interesting 2 to talk about a very current activity, taking place around the time meeting. of speaking 3 Use could / should + infinitive to predict. They are pushing the area for development. It could / should turn out to be quite an interesting conference. 3 to talk about fixed plans or arrangements in the future I am meeting the management committee on Friday. -

Grammar 4 – the Perfect Tenses the Present Perfect – an Introduction

Grammar 4 – The Perfect Tenses Welcome to a minefield! No, it’s not all that bad really, although gaining mastery of the Perfect Tense system is something which many students find difficult. Some students master the present and past, and appear to embrace the future forms with relative ease, yet fail to comprehend how and when to use the Perfect Tenses. We have seen many a good intermediate student fail to make additional progress because they have been unable to get to grips with this tense. So what is it all about? In this section we will look at 3 perfect forms; Past, Present and Future. The Present Perfect – an introduction The Present Perfect is a way of linking the past to the present. Whether it exists in other languages or not, it is a traditionally difficult concept for students to grasp and a notorious bugbear for teachers. A good sign of fluency in the English language is the ability to use it correctly. Do not attempt to teach the Present Perfect without the aid of a good grammar book (at least until you are familiar with it - we recommend ‘The Good Grammar Book’ by Swan). It is worth ensuring you become familiar with this tense as common interview questions for jobs include the following: ‘Describe the 3 uses of the Present Perfect’ ‘How would you approach a lesson on the Present Perfect?’ ‘How would you explain the difference between the Past Simple and the Present Perfect Tenses to a class?’ By the end of this module you should be able to answer these questions. -

The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative Analysis)

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2012, том 51, серия 6.3 The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative analysis) Tamar Mikeladze, Manana Napireli, Seda Asaturovi Abstract: The paper presents comparative analysis of the past perfect in German, English and Old Russian. It studies the formation of this complex tense and its use in these three languages. The past perfect doesn’t exist in Modern Russian any more, but historical Russian past perfect conveyed more similarities with English and German past perfect than differences. These observations will be helpful in teaching the past perfect to the learners of these languages and translation of Old Russian documents. Key words: Perfect, Past perfect, Old Russian, Plusquamperfekt, Indo-European languages, differences and similarities of Indo-European languages INTRODUCTION The popularity of typological analysis of languages has been increased recently. The purpose of our paper is a comparative analysis of English, German and Old Russian Perfect tense. In linguistics, the perfect is a combination of aspect and tense, that calls a listener's attention to the consequences, at some time of perspective (time of reference), generated by a prior situation, rather than just to the situation itself. The time of perspective itself is given by the tense of the helping verb, and usually the tense and the aspect are combined into a single tense-aspect form: the present perfect, the past perfect (also known as the pluperfect), or the future perfect. The difference between the perfect and non-perfect forms of the verb, according to the tense interpretation of the perfect, consists in the fact that the perfect denotes a secondary temporal characteristic of the action. -

An Analysis of Use of Conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 8 No. 2; April 2017 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia An Analysis of Use of conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English Sadam Haza' Al Rdaat Coventry University, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Received: 04/01/2017 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Accepted: 17/02/2017 Abstract Conditional sentences are made of two clauses namely “if-clause” and “main clause”. Conditionals have been noted by scholars and grammarians as a difficult area of English for both teachers and learners. The two clauses of conditional sentences and their form, tense and meaning could be considered the main difficulty of conditional sentences. In addition, some of non-native speakers do not have sufficient knowledge of the differences between conditional sentences in the two languages and they tried to solve their problems in their second language by using their native language. The aim of this study was to analyse the use of conditional sentences by Arab students of English in semantic and syntactic situations. For the purpose of this study, 20 Arab students took part in the questionnaire, they were all studying different subjects and degrees (bachelor, master and PhD) at Coventry University. The results showed that the use of type three conditionals and modality can be classified as the most difficult issues that students struggle to understand and use. Keywords: conditional sentences, protasis and apodosis, mood, real and unreal clauses, tense-time 1.