Front Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcnamara According to Hendrickson--Power Corrupts

Paul Hendrickson. The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996. ix + 427 pp. $27.50, cloth, ISBN 978-0-679-42761-2. Reviewed by Oscar Patterson Published on H-PCAACA (December, 1996) Robert McNamara was president of Ford Mo‐ and at least two dead, and it was only a troop-fer‐ tor Company, president of the World Bank, and rying mission. Secretary of Defense under presidents John F. Norman Morrison's picture didn't make the Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. He was completely cover of Life. Morrison, a Quaker, drenched his confident in the technological and military capaci‐ clothes with kerosene and struck a match. Direct‐ ty of the United States. But it took him thirty years ly below McNamara's office window in the Penta‐ to admit that "we were wrong, terribly wrong" in gon, Norman Morrison burned to death protest‐ the decisions made about Vietnam. If the num‐ ing the war in Vietnam. He dropped his daughter, bers worked, McNamara believed, all else fol‐ Emily, seconds before the fames completely con‐ lowed. sumed him. The Living and the Dead is painstakingly re‐ Marlene Vrooman went to Vietnam straight searched and often at odds with McNamara's own from a Catholic nursing program. Like most Army version of events. It examines his life in Califor‐ nurses, she was young and inexperienced. She nia, his career at Ford Motor Company, and his saw little blood during her training, but at Qui Vietnam-era decisions. It is Hendrickson's selec‐ Nhon in 1966 her unit treated 115 cases in under tion of those decisions and his exposition of how thirty hours. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Korea and Vietnam: Limited War and the American Political System

Korea and Vietnam: Limited War and the American Political System By Larry Elowitz A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1972 To Sharon ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express his very deep appreciation to Dr. John W. Spanier for his valuable advice on style and structure. His helpful suggestions were evident throughout the entire process of writing this dissertation. Without his able supervision, the ultimate completion of this work would have been ex- ceedingly difficult. The author would also like to thank his wife, Sharon, whose patience and understanding during the writing were of great comfort. Her "hovering presence," for the "second" time, proved to be a valuable spur to the author's research and writing. She too, has made the completion of this work possible. The constructive criticism and encouragement the author has received have undoubtedly improved the final product. Any shortcomings are, of course, the fault of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES viii ABSTRACT xii CHAPTER 1 THE AMERICAN POLITICAL SYSTEM AND LIMITED WAR 1 Introduction 1 American Attitudes 6 Analytical Framework 10 Variables and Their Implications 15 2 PROLOGUE--A COMPARISON OF THE STAKES IN THE KOREAN AND VIETNAM WARS 22 The External Stakes 22 The Two Wars: The Specific Stakes. 25 The Domino Theory 29 The Internal Stakes 32 The Loss of China Syndrome: The Domestic Legacy for the Korean and Vietnam Wars 32 The Internal Stakes and the Eruption of the Korean War 37 Vietnam Shall Not be Lost: The China Legacy Lingers 40 The Kennedy and Johnson Administra- tions: The Internal Stakes Persist . -

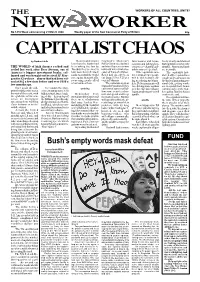

Bush's Empty Words Mask Defeat

THE WORKERS OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE! NEWNo 1478 Week commencing 21 March 2008 Weekly paperWORKER of the New Communist Party of Britain 60p CAPITALIST CHAOS by Daphne Liddle These measures were England’s Monetary foreclosures and repos- fectly clearly and showed less than the banks had Policy Committee had met sessions and falling prop- that capitalism is inherently THE WORLD of high finance rocked and been asking for, but by and voted by seven to two erty prices – digging capi- unstable. Booms and busts reeled last week after Bear Stearns, one of Tuesday they seemed to not to cut interest rates be- talism into a deeper hole. are inevitable. America’s biggest investment banks, col- have done the trick. Stock cause of fears of inflation. If the capitalists raise The capitalists have lapsed and was bought out by rival JP Mor- markets around the world Rates had already been interest rates fewer people staved off recession for a gan for $2-a-share – shares that had been val- rose again, dramatically, cut from 5.5 to 5.25 per will be able to buy, lead- couple of decades now on ued at $62 a few days before and over $150 a recovering nearly all of cent in February. ing to a drying up of mar- the basis of promoting per- few months ago. what had been lost. The capitalists are in an kets. Debt repayments will sonal debt, getting work- impossible position. If they rise, driving more workers ers to spend their future Once again the sub- In London the Gov- tumbling cut interest rates it will al- over the edge into collapse. -

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing

November 1965 Over 40,000 protesters led by several student activist Progression / Escalation of Anti-War groups surrounded the White House, calling for an end to the war, and Sentiment in the Sixties, 1963-1971 then marched to the Washington Monument. On that same day, President Johnson announced a significant escalation of (Page 1 of 2) U.S. involvement in Indochina, from 120,000 to 400,000 troops. May 1963 February 1966 A group of about 100 veterans attempted to return their The first coordinated Vietnam War protests occur in London and Australia. military awards/decorations to the White House in protest of the war, but These protests are organized by American pacifists during the annual were turned back. remembrance of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. In the first major student demonstration against the war hundreds of students March 1966 Anti-war demonstrations were again held around the country march through Times Square in New York City, while another 700 march in and the world, with 20,000 taking part in New York City. San Francisco. Smaller numbers also protest in Boston, Seattle, and Madison, Wisconsin. April 1966 A Gallup poll shows that 59% of Americans believe that sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake. Among the age group of 21-29, 1964 Malcolm X starts speaking out against the war in Vietnam, influencing 71% believe it was a mistake compared to only 48% of those over 50. the views of his followers. May 1966 Another large demonstration, with 10,000 picketers calling for January 1965 One of the first violent acts of protest was the Edmonton aircraft an end to the war, took place outside the White House and the Washington bombing, where 15 of 112 American military aircraft being retrofitted in Monument. -

It's Not As Simple As Whose Side You Were On

It's not as simple as whose side you were on Vietnam March 9, 2007 Christian G. Appy's big oral history of the Vietnam War was first published in the US in 2003 under the title Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides . So far as I know, the American public has not been given a list of titles of the books read by President George W. Bush in his widely publicised contest with political adviser Karl Rove to see who could read the most books in the year 2006. But what if the now retitled Vietnam: The Definitive Oral History, Told from All Sides were on the President's list? What lessons would he extract from these accounts of how events in Vietnam from 1945 to 1975 affected human lives? Would he reinsert the flat notion of patriotism found in the American title? Would he reduce all sides to two and prefer one, with his trademark moral certitude? Would he have second thoughts about current US foreign policy? Good oral histories, such as Joan and Robert K. Morrison's From Camelot to Kent State (2001), depend on how well the oral historians choose their informants and then use what their informants have to say. In a personally moving preface with two useful maps, Appy tells us that he interviewed 350 people in 25 American states and across the new united Vietnam during the period 1998-2003. He used less than half of these in his book. Some major figures, such as Henry Kissinger and Nguyen Van Thieu, refused to be interviewed. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC -

Vietnam January-August 1963

III. BEGINNING OF THE BUDDHIST CRISIS, MM 9-JUNE 16: INCIDENT IN HUE, THE FIVE BUDDHIST DEMANDS, USE OF TEAR GAS IN HUE, SELF- IMMOLAHON OF QUANG DUC, NEGOTIAl-IONS IN SAIGON TO RESOLVE THE CRISIS, AGREEMENT ON THE FIVE DEMANDS 112. Telegram From the Consulate at Hue to the Department of State’ Hue, May 9, 1963-3 p.m. 4. Buddha Birthday Celebration Hue May 8 erupted into large- scale demonstration at Hue Radio Station between 2000 hours local and 2330 hours. At 2245 hours estimated 3,000 crowd assembled and guarded by 8 armored cars, one Company CG, one Company minus ARVN, police armored cars and some carbines fired into air to disperse mob which apparently not unruly but perhaps deemed menacing by authorities. Grenade explosion on radio station porch killed four chil- dren, one woman, Other incidents, possibly some resulting from panic, claimed two more children plus one person age unknown killed. Total casualties for evening 8 killed, 4 wounded. ’ I Source: Department of State, Central Files, POL 25 S VIET. Secret; Operational Immediate. Received at 8:33 a.m. 2 At 7 p.m. the Embassy in Saigon sent a second report of the incident to Washing- ton, listing seven dead and seven injured. The Embassy noted that Vietnamese Govern- ment troops may have fired into the crowd, but most of the casualties resulted, the Embassy reported, from a bomb, a concussion grenade, or “from general melee”. The Embassy observed that although there had been no indication of Viet Cong activity in connection with the incident, the Viet Cong could be expected to exploit future demon- strations. -

Issues of the Sixties Inside Pages of the Detroit Fifth Estate, 1965-1970

TITLE Capturing Detroit Through An Underground Lens: Issues of the Sixties Inside Pages of the Detroit Fifth Estate, 1965-1970. By Harold Bressmer Edsall, III Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date March 8, 2010 First Reader Second Reader t Capturing Detroit Through An Underground Lens: Issues of the Sixties Inside Pages of the Detroit Fifth Estate Newspaper, 1965-1970 CONTENTS Introduction 2/5ths In Every Garage 2 Chapter 1 Life in the Fourth Estate: Someone Had to Testify 12 Chapter 2 Origins of The Fifth Estate : Hard to Miss The 55 Black and White Coalition Chapter 3 Antiwar News: The Fifth Estate “A Peddler of 89 Smut” Chapter 4 The Fifth Estate , The Underground Press Syndicate, 126 And Countercultural Revenues Chapter 5 Time, Life, Luce, LBJ, LSD, and theFifth Estate 163 APPENDIX Distortion of an UM-Flint Graduate 200 BIBLIOGRAPHY 207 2 Introduction: 2/5ths In Every Garage 3 In December 1968 editors of the Detroit Fifth Estate (FE ), what was referred to as an “underground newspaper,” shared with its readers that “A girl wrote us from Britton, Mich, and told us that she had been caught selling papers to Adrian College students and got busted by her high school principal.”1 The authorities threatened the young lady with criminal charges for selling “pornographic literature, contributing to the delinquency of minors, and selling without a permit.”2 FE stated, “This goes on all the time, but it won’t turn us around. -

SNIE 53-2-63 the Situation in South Vietn~M 10 July 1963

SNIE 53-2-63 The Situation in South Vietn~m I I 10 July 1963 This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com A~PROVED FOR RELEASE DATE: 'JAN 2005 THE SITUATldlN IN SOUTH VIETNAM r SCOPE NOTE I NIE 53-63, "Prospects in South Vietnam," dated 17 April 1963 was particularly concerned with the progress of the Jounterin surgency effort, and with the military and political fadtors most likely to affect that effort. The primary purpose of tHe present SNIE is to examine the implications of recent in develo~mentsI South Vietnam for the stability of the country, the viability of the piem regime, and its relationship with the US. ! CONCLUSIONS A. The Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam has highlighted and intensified a widespread and longstanding dissatisfacrbon with the Diem regime and its style of government. If-as is likely Diem fails to carry out truly and promptly the commitments he has made to the Buddhists, disorders will probably ftkre again and the chances of a coup or assassination attempts ag~inst him will become better than even. (Paras. 4, 14) I B. The Diem regime's underlying uneasiness about t~e extent of the US involvement in South Vietnam has been sharpened I by the Buddhist aflair and the firm line taken by the US. -

Protest by Fire: Essay on a Paroxysmal Element

Protest by Fire: Essay on a Paroxysmal Element By Richard A. Hughes M.B. Rich Professor of Religion Lycoming College 700 College Place Williamsport, PA 17701−5192 USA 1 Introduction In his book The Psychoanalysis of Fire Gaston Bachelard presents a theory of fire as a fundamental element. He points out that life accounts for all slow changes, but fire creates quick changes. Fire “rises from the depths of the substance and offers itself with the warmth of love. Or it can go back down into the substance and hide there, latent and pent-up, like hate and vengeance” (Bachelard 1964: 7). In the same context Bachelard observes that fire is the only element to which “the opposing values of good and evil” may be attributed. “It shines in Paradise. It burns in hell. It is gentleness and torture. It is cookery and it is apocalypse.” Bachelard goes on to explain that fire has a sexual nature. From the age of prehistoric societies to the present sexual intimacy has been the model for the objective production of fire. Rubbing two pieces of wood together to start a fire would be analogous to the rubbing together in the sexual act (Bachelard 1964: 23−24). He collects examples of the rubbing together analogy in Germanic, Scottish, and Native American rituals. Bachelard believes that since ancient times fire has been a sexual element as expressed in dreams, symbols, and moral values. Bachelard’s provocative study betrays an ambiguity between the sexual nature of fire and moral values. In this paper I contend that fire as a symbol pertains psychologically to moral experience rather than to sexuality.