Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions Special Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa 1952-1953

SUMMARY OF RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN AFRICA 1952-53 Supplement to World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS UMMARY OF C T ECONOMIC EVE OPME TS IN AF ICA 1952-53 Supplement World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS New York, 1954 E/2582 ST/ECA/26 May 1954 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sal es No.: 1951\..11. C. 3 Price: $U.S. $0.80; 6/- stg.; Sw.fr. 3.00 (or equivalent in other currencies) FOREWDRD This report is issued as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1952-53, and has been prepared in response to resolution 367 B (XIII) of the Economic and Social Council. It presents a brief analysis of economic trends in Africa, not including Egypt but including the outlying islands in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, on the basis of currently available statistics of trade, production and development plans covering mainly the year 1952 and the first half of 1953, Thus it carries forward the periodic surveys presented in previous years in accordance with resolution 266 (X) and 367 B (XIII), the most recent being lIRecent trends in trade, production and economic development plansll appearing as part II of lIAspects of Economic Development in Africall issued in April 1953 as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1951-52, The present report, like the previous ones, was prepared in the Division of Economic Stability and Development of the United Nations Department of Economic Affairs. EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS The following symbols have been used in the tables throughout the report: Three dots ( ... ) indicate that data -

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: the U.S

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs November 3, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41473 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Summary The United States government has implemented a range of programs to counter violent extremist threats in East Africa in response to Al Qaeda’s bombing of the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998 and subsequent transnational terrorist activity in the region. These programs include regional and bilateral efforts, both military and civilian. The programs seek to build regional intelligence, military, law enforcement, and judicial capacities; strengthen aviation, port, and border security; stem the flow of terrorist financing; and counter the spread of extremist ideologies. Current U.S.-led regional counterterrorism efforts include the State Department’s East Africa Regional Strategic Initiative (EARSI) and the U.S. military’s Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), part of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). The United States has also provided significant assistance in support of the African Union’s (AU) peace operations in Somalia, where the country’s nascent security forces and AU peacekeepers face a complex insurgency waged by, among others, Al Shabaab, a local group linked to Al Qaeda that often resorts to terrorist tactics. The State Department reports that both Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab pose serious terrorist threats to the United States and U.S. interests in the region. Evidence of linkages between Al Shabaab and Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, highlight another regional dimension of the threat posed by violent extremists in the area. -

The Kenyan British Colonial Experience

Peace and Conflict Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Decolonizing Through a Peace and Article 2 Conflict Studies Lens 5-2018 Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience Peter Karari [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Karari, Peter (2018) "Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience," Peace and Conflict Studies: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.46743/1082-7307/2018.1436 Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs/vol25/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace & Conflict Studies at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace and Conflict Studies by an authorized editor of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience Abstract Colonialism can be traced back to the dawn of the “age of discovery” that was pioneered by the Portuguese and the Spanish empires in the 15th century. It was not until the 1870s that “New Imperialism” characterized by the ideology of European expansionism envisioned acquiring new territories overseas. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 prepared the ground for the direct rule and occupation of Africa by European powers. In 1895, Kenya became part of the British East Africa Protectorate. From 1920, the British colonized Kenya until her independence in 1963. As in many other former British colonies around the world, most conspicuous and appalling was the modus operandi that was employed to colonize the targeted territories. -

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 The Foundation of Kenya Colony I. P[ublic] R[ecord] O[ffice] Kew CO 533/234 ff 432-44. Kenya was how Johann Krapf, the German missionary who was in 1849 the first white man to see the mountain, transliterated the Kamba pronunciation of the Kikuyu name for it, Kirinyaga. The Kamba substituted glottal stops for intermediate consonants, hence 'Ki-i-ny-a'. T. C. Colchester, 'Origins of Kenya as the Name of the Country', Rhodes House. Mss Afr s.1849. 2. PRO CO 822/3117 Malcolm MacDonald to Duncan Sandys. Secret and Personal. 18 September 1963. 3. The new rail routes in question were the Uasin Gishu line and the Thika extension. M. F. Hill, Permanent Way. The StOlY of the Kenya and Uganda Railway (Nairobi: East African Railways and Harbours, 2nd edn 1961), p. 392. 4. Daily Sketch, 5 July 1920, p. 5. 5. Sekallyolya ('the crane [or stork] looking out on the world') was first printed in Nairobi in the Luganda language in 1921. From time to time it brought out editions in Swahili and for special occasions in English. Harry Thuku's Tangazo was the first Kenya African single sheet newsletter. 6. Interview with James Beauttah, Fort Hall, 1964. Beauttah was one of the first English-speaking African telephone operators. He claimed to be the first African to have electricity in his house. 7. PRO FO 2/377 A. Gray to FO, 16 February 1900, 'Memo on Report of Law Officers of the Crown reo East Africa and Uganda Protector ates'. The effect of the opinion of the law officers is that Her Majesty has, by virtue of her Protectorate, entire control over all lands unappropriated .. -

Meteorologia

MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 15/SDOP, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 2006. Aprova a reedição da Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, inciso IV, da Portaria DECEA n°136-T/DGCEA, de 28 de novembro de 2005, RESOLVE: Art. 1o Aprovar a reedição da ICA 105-1 “Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas”, que com esta baixa. Art. 2o Esta Instrução entra em vigor em 1º de setembro de 2006. Art. 3o Revoga-se a Portaria DECEA nº 131/SDOP, de 1º de julho de 2003, publicada no Boletim Interno do DECEA nº 124, de 08 de julho de 2003. (a) Brig Ar RICARDO DA SILVA SERVAN Chefe do Subdepartamento de Operações do DECEA (Publicada no BCA nº 146, de 07 de agosto de 2006) MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 33 /SDOP, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 2007. Aprova a edição da emenda à Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, alínea g, da Portaria DECEA n°34-T/DGCEA, de 15 de março de 2007, RESOLVE: Art. -

Rank 030 Adani Enterprises Ltd

Thinking Big Doing Better Adani Enterprises Limited Annual Report 2016-17 01-05 12-13 20-21 Corporate Snapshot Renewable Energy Managing Director’s Review 06-09 14-15 22-23 Coal mining and trading City Gas Distribution Financial Performance 10-11 16-19 24-31 Agri Business Chairman’s Statement Corporate Social Responsibility Forward-looking statement In this annual report, we have disclosed forward-looking information to enable investors to comprehend our prospects and take informed investment decisions. This report and other statements - written and oral - that we periodically make contain forward-looking statements that set out anticipated results based on the management’s plans and assumptions. We have tried wherever possible to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipates’, ‘estimates’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, ‘believes’, and words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. We cannot guarantee that these forward-looking statements will be realised, although we believe we have been prudent in our assumptions. The achievement of results is subject to risks, uncertainties and even inaccurate assumptions. Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual results could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. Readers should bear this in mind. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. At Adani Enterprises Limited, we are present in several important national sectors that help build the nation. These sectors include coal management, renewable energy, edible oil, agri-storage and city gas distribution. -

Central Organization of Trade Unions (Kenya)

CENTRAL ORGANIZATION OF TRADE UNIONS (KENYA) 14TH QUINQUENNIAL CONFERENCE SECRETARY GENERAL’S REPORT 9TH APRIL, 2021 TOM MBOYA LABOUR COLLEGE, KISUMU Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... 1 Foreword: Chairman General ........................................................................................................ 3 Foreword: Secretary-General ........................................................................................................ 4 Foreword: Treasurer General ......................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgement.......................................................................................................................... 7 Obituaries ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 10 1.1 About COTU (K) ......................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Vision ........................................................................................................................ 10 1.3 Mission ...................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Values and Principles -

2004 Fall Inaug ENS ( .Pdf )

C. G. C. JOURNAL - Raíces de la Perla - Inaugural Edition Fall 2004 HIHIHIHIHIHIHIHIHIHIHIHIHI The Espada Project: Are your ancestors dying to meet you? The Streets of Havana: Find the bit of realty your forefathers called home. Origen del Linaje de Grave de Peralta en Cuba Del Presidente Bienvenido al primer Boletín del CGC: "Raíces de mejor. Los miembros de la Directiva y yo la Perla!" Estamos muy contentos de poderles deseamos que nos digan su opinión! ofrecer nuevas perspectivas sobre recursos, Necesitamos tener interacción con todos, y que ideas y también instrucciones para hacer todos se sientan involucrados en estos proyectos. búsquedas más efectivas sobre nuestros La búsqueda de nuestros antepasados cubanos antepasados. El Boletín es sólo un paso más de tiene características especiales y nos enfrentamos los muchos que la Directiva está tomando para a problemas que otros genealogistas no tienen. hacer cada vez más sustanciales los beneficios Uno de los beneficios más importantes de este de la membresía. También hemos creado un club, es el poder conocer a otros que nos pueden manual de principiantes donde nos concentramos ayudar. Asistir a las reuniones y conocer a los en hacer más fácil y llevadero el comienzo de la otros miembros es el mayor y mejor recurso que búsqueda genealógica cubana, aunque también le podemos ofrecer. Se crearan nuevas amistades hay información interesante para aquellos que ya que, tal vez, pueda que sean primos! Para termi- son veteranos en la materia. Por favor, recuerde nar, la Directiva quiere agradecer a Martha pedir su copia en la próxima reunión. También Moreira, miembro fundador del club y una de las estamos esforzándonos en hacer una selección anteriores Presidentas, por su creatividad al su- de tópicos de interés para próximas presenta- gerir el nombre de este Boletín. -

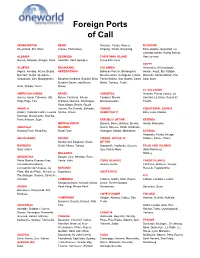

PORTS of CALL WORLDWIDE.Xlsx

Foreign Ports of Call AFGHANISTAN BENIN Shantou, Tianjin, Xiamen, ECUADOR Kheyrabad, Shir Khan Cotnou, Porto-Novo Xingang, Yantai, Zhanjiang Esmeraoldas, Guayaquil, La Libertad, Manta, Puerto Bolivar, ALBANIA BERMUDA CHRISTMAS ISLAND San Lorenzo Durres, Sarande, Shegjin, Vlore Hamilton, Saint George’s Flying Fish Cove EGYPT ALGERIA BOSNIAAND COLOMBIA Alexandria, Al Ghardaqah, Algiers, Annaba, Arzew, Bejaia, HERZEGOVINA Bahia de Portete, Barranquilla, Aswan, Asyut, Bur Safajah, Beni Saf, Dellys, Djendjene, Buenaventura, Cartagena, Leticia, Damietta, Marsa Matruh, Port Ghazaouet, Jijel, Mostaganem, Bosanka Gradiska, Bosakni Brod, Puerto Bolivar, San Andres, Santa Said, Suez Bosanki Samac, and Brcko, Marta, Tumaco, Turbo Oran, Skikda, Tenes Orasje EL SALVADOR AMERICAN SAMOA BRAZIL COMOROS Acajutla, Puerto Cutuco, La Aunu’u, Auasi, Faleosao, Ofu, Belem, Fortaleza, Ikheus, Fomboni, Moroni, Libertad, La Union, Puerto El Pago Pago, Ta’u Imbituba, Manaus, Paranagua, Moutsamoudou Triunfo Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de ANGOLA Janeiro, Rio Grande, Salvador, CONGO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ambriz, Cabinda, Lobito, Luanda Santos, Vitoria DEMOCRATIC Bata, Luba, Malabo Malongo, Mocamedes, Namibe, Porto Amboim, Soyo REPUBLIC OF THE ERITREA BRITISH VIRGIN Banana, Boma, Bukavu, Bumba, Assab, Massawa ANGUILLA ISLANDS Goma, Kalemie, Kindu, Kinshasa, Blowing Point, Road Bay Road Town Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka ESTONIA Haapsalu, Kunda, Muuga, ANTIGUAAND BRUNEI CONGO, REPUBLIC Paldiski, Parnu, Tallinn Bandar Seri Begawan, Kuala OF THE BARBUDA Belait, Muara, Tutong -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Despatches and registers of despatches sent to, and received from, the Colonial Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Secretary established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 that FCO 141/2180-2186, 2192-2245, 2248-2249, 2260, 2264-2273: the entire island came under British control. In Open, confidential and secret despatches covering a variety of topics including the acts and ordinances, 1948, Ceylon became a self-governing state and a the economy, agriculture and produce, lands and buildings, imports and exports, civil aviation, railways, member of the British Commonwealth, and in 1972 banks and prisons. Despatches regarding civil servants include memorials, pensions, recruitment, dismissals it became the independent republic under the name and suggestions for New Year’s honours. 1872-1948, with gaps. The years 1897-1903 and 1906 have been of Sri Lanka. release in previous tranches. Below is a selection of files grouped according to Telegrams and registers of telegrams sent to and received from the Colonial Secretary theme to assist research. This list should be used in conjunction with the full catalogue list as not all are FCO 141/2187-2191, 2246-2247, 2250-2263, 2274-2275 : included here. The files cover the period between Open, confidential and secret telegrams on topics such as imports and exports, defence costs and 1872 and 1948 and include a substantial number of regulations, taxation and the economy, the armed forces, railways, prisons and civil servants 1899-1948. -

Unbound, Volume 9

UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Journal of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 9 2016 UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Unbound: A Review of Legal History and Rare Books (previously published as Unbound: An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books) is published by the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Li- braries. Articles on legal history and rare books are both welcomed and encouraged. Contributors need not be members of the Legal His- tory and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American As- sociation of Law Libraries. Citation should follow any commonly-used citation guide. Cover Illustration: This depiction of an American Bison, en- graved by David Humphreys, was first published in Hughes Ken- tucky Reports (1803). It was adopted as the symbol of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section in 2007. BOARD OF EDITORS Mark Podvia, Editor-in-Chief Associate University Librarian West Virginia University College of Law Library P.O. Box 6130 Morgantown, WV 26506 Phone: (304)293-6786 Email: [email protected] Noelle M. Sinclair, Executive Editor Head of Special Collections The University of Iowa College of Law 328 Boyd Law Building Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone (319)335-9002 [email protected] Kurt X. Metzmeier, Articles Editor Associate Director University of Louisville Law Library Belknap Campus, 2301 S. Third Louisville, KY 40292 Phone (502)852-6082 [email protected] Joel Fishman, Ph.D., Book Review Editor Assistant Director for Lawyer Services Duquesne University Center for Legal Information/Allegheny Co.