Culturally Centered Music and Imagery with Indian Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India September 2019

Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India September 2019 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Contents Foreword by IMI 04 Foreword by Deloitte India 05 Glossary 06 Executive summary 08 Indian recorded music industry: Size and growth 11 Indian music’s place in the world: Punching below its weight 13 An introduction to economic impact: The amplification effect 14 Indian recorded music industry: First order impact 17 “Formal” partner industries: Powered by music 18 TV broadcasting 18 FM radio 20 Live events 21 Films 22 Audio streaming OTT 24 Summary of impact at formal partner industries 25 Informal usage of music: The invisible hand 26 A peek into brass bands 27 Typical brass band structure 28 Revenue model 28 A glimpse into the lives of band members 30 Challenges faced by brass bands 31 Deep connection with music 31 Impact beyond the numbers: Counts, but cannot be counted 32 Challenges faced by the industry: Hurdles to growth 35 Way forward: Laying the foundation for growth 40 Conclusive remarks: Unlocking the amplification effect of music 45 Acknowledgements 48 03 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Foreword by IMI CIRCA 2019: the story of the recorded Nusrat Fateh Ali-Khan, Noor Jehan, Abida “I know you may not music industry would be that of David Parveen, Runa Laila, and, of course, the powering Goliath. The supercharged INR iconic Radio Ceylon. Shifts in technology neglect me, but it may 1,068 crore recorded music industry in and outdated legislation have meant be too late by the time India provides high-octane: that the recorded music industries in a. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Galgotias University, India Mr

The Researcher International Journal of Management Humanities and Social Sciences January-June, 2019 Issue 01 Volume 04 Chief Patron Mr. Suneel Galgotia, Chancellor, Galgotias University, India Mr. Dhruv Galgotia, CEO, Galgotias University, India Patron Prof.(Dr.) Renu Luthra Vice Chancellor, Galgotias University, India GALGOTIASEditor-in -UNIVERSITYChief Dr. Adarsh Garg Galgotias University Publication SCIENCE IN THE CONTEXT OF SOCIETY THROUGH QR CODE IN PROBLEM BASED LEARNING Science in the Context of Society through QR Code in Problem Based Learning David Devraj Kumar1 Susanne I. Lapp2 Abstract Science education in the context of societal applications through QR code in problem-based learning (PBL) is addressed in this paper. An example from an elementary classroom where the students received mentoring by their high school peers to develop QR codes involving the Florida Everglades is presented. Through meaningful guidance it is possible to enhance elementary students knowledge of science in society and awaken their curiosity of science using QR code embedded problem-based learning. Key Words: QR Code, Problem Based Learning, Science in Society, Mentor 1. Introduction How to connect classroom science to societal applications in problem-based learning (PBL) through QR code is explored in this paper. We live in a world highly influenced and impacted by science and its technological applications. Science and its application in technology are an integral part of society. One of the goals of science education is preparing students to be critical thinkers and problem solvers who understand the role of science and technology in society [1]. Currently, the US focus has followed a standards-driven model for educating students. -

The Optic and the Semiotic in the Novels of Amit Chaudhuri

THE OPTIC AND THE SEMIOTIC IN THE NOVELS OF AMIT CHAUDHURI SUMANA ROY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR Ph.D DEGREE UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROFESSOR G. N. RAY AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL, 2007 g23-033 •3< ggg'O 20582O 2 6 MAY li^Oti Contents Acknowledgements 1 Preface 2 Introduction 6 Chapter 1 The Text as Rhizome: Amit Chaudhuri's Theory of Fiction 16 Chapter 2 Whose Space is it anyway? The Politics of Translation on the Printed Page 26 Chapter 3 The Metonymised Body: Exploring the Semiotic of the Body 44 Chapter 4 Salt, Sugar, Spice: The Food Dis(h)-course 62 Chapter 5 This is Not Fusion: Then what is? 84 Chapter 6 'Eh Stupid!' 'Saala!': The 'Impolite' in Chaudhuri's Fiction 97 Chapter 7 Under Cover: The Cover Illustrations of the Books of Amit Chaudhuri 121 Chapter 8 "I send you this poem": The optic and the codes of exchange in Chaudhuri's Poems 128 Bibliography 148 Appendix Aalap: In Conversation with Amit Chaudhuri 154 Novelist on Narratives 178 Published Chapters 184 Acknowledgements Every PhD student begins by acknowledging her gratitude and debt to her supervisor and I will continue with the tradition; only, in my case, my gratitude would extend to subjects beyond the scope of this dissertation. Among all the generous gifts that I have received from Professor G. N. Ray, I must mention one that I value over others - his patience with a moody doctoral student like me. I would also like to acknowledge my gratitude to two of my professors. -

Für Sonntag, 21

Tägliche BeatlesInfoMail 29.12.20: I want to tell you /// Zwei Mal THINGS 343 - jeweils auf Deutsch und Englisch /// MANY YEARS AGO ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Im Beatles Museum erhältlich: Zwei Mal THINGS 343 - jeweils auf Deutsch und Englisch Versenden wir gut verpackt als Brief (mit Deutscher Post). Abbildungen von links: Titelseite und Inhaltsverzeichnis für deutsches THINGS 343 / alle 40 Seiten (verkleinert) Deutsches BEATLES-Magazin THINGS 343. 4,00 € inkl. Versand Herausgeber: Beatles Museum, Deutschland. 1617-8114. Heft, A5-Format, 40 Seiten; viele Farb- und Schwarzweiß-Fotos; deutschsprachig. Schwerpunktthemen (mindestens eine Seite): MANY YEARS AGO: BEATLES-Aufnahmen für das Album RUBBER SOUL. / PAUL McCARTNEY, RINGO STARR, JOHN LENNON, GEORGE HARRISON 1970. / JOHN LENNON und YOKO ONO - Interviews und Fotos im Cafe La Fortuna, New York. / JOHN LENNON und YOKO ONO - die Kimono-Fotos. / GEORGE und OLIVIA HARRISON besuchen Christie’s in London. / GEORGE HARRISON produziert neues My Sweet Lord-Video. / RINGO STARR auf Veranstaltung IMAGINE THERE’S NO HUNGER. / NEWS & DIES & DAS: BADFINGER-Mitglied JOEY MOLLAND mit neuen Versionen von drei Songs und neuem BADFINGER-Album. / 1966er BEATLES-Auftritt beim „‘New Musical Express’ Poll Winners Concert“. / „Record Store Day 2020“-Veröffentlichungen mit BEATLES-Bezug. / Buch BEATLEMANIA - FOUR PHOTOGRAPHERS ON THE FAB FOUR. / PAUL McCARTNEY-Album McCARTNEY III. Kompletter Inhalt: Coverfoto: THE BEATLES am Mittwoch 3. November 1965 im EMI Recording Studio 2 beim Aufnehmen von Songs für das nächste Album, RUBBER SOUL. Angebot / Info: Buch/Fotoband ASTRID KIRCHHERR WITH THE BEATLES. Seite halb Vier: BEATLES CLUB WUPPERTAL trauert um Doris Schulte-Albrecht. Impressum: Infos zum Beatles Museum und zu THINGS. Hallo M.B.M., die nächsten 40 Jahre. -

ENIL Corporate PPT Feb 2009

IDFC SSKI Emerging Stars Conference 2009 February 5, 2009 1 Disclaimer Certain statements in this release concerning our future growth prospects are forward-looking statements, which involve a number of risks, and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those in such forward-looking statements. The risks and uncertainties relating to these statements include, but are not limited to, risks and uncertainties regarding fluctuations in earnings, our ability to manage growth, intense competition in our business segments, change in governmental policies, political instability, legal restrictions on raising capital, and unauthorized use of our intellectual property and general economic conditions affecting our industry. ENIL may, from time to time, make additional written and oral forward looking statements, including our reports to shareholders. The Company does not undertake to update any forward-looking statement that may be made from time to time by or on behalf of the company. 2 Presentation Path • Times Group • Indian Media Industry • ENIL Overview • Financial Highlights • Strategic Direction 3 Times Group 4 Corporate Structure Bennett Coleman & Co. Limited Publishing Division Times Internet Times Global Private The Times of India Limited Broadcasting Treaties The Economic Times Navbharat Times indiatimes.com News Channel – Maharashtra Times Times 58888 Times Now Sandhya Times Infotainment Business News Times of Money Vijay Times Media Limited – ET Now Zoom Entertainment & Retail Entertainment -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

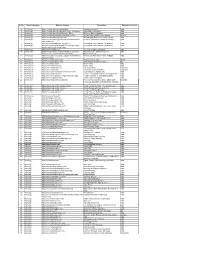

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

Mantras and Sacred Chants

1 Peace Mala Mantras and Sacred Chants Mantras or sacred chants are often written in Sanskrit which is an ancient sacred language from India. Many of the holy books linked with Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism are written in this language. The word ‘mala’, is from the Sanskrit language and means ‘garland of flowers’. In the East a mala is a string of beads used in meditation or prayer as each bead or ‘flower’ focuses on a prayer or mantra. You can see mala beads in this photo where the Buddhist practitioner is about to chant mantras to Medicine Buddha. Copyright © Pam Evans 2011 (revised 2020) www.peacemala.org.uk “Creative education that empowers and embraces all Uniting the World in Peace” “Addysg greadigol sy’n grymuso ac yn cofleidio pawb Uno'r Byd mewn Heddwch” 2 The word ‘mantra’ is also from the Sanskrit language and describes a sacred sound or group of words used in chanting. Mantras are repeated in order to focus the mind or consciousness. The oldest mantras composed in Sanskrit are at least 3000 years old. Some teachers refer to mantras as ‘mind protection’ or ‘secret speech’. This is because concentrating on mantras, and counting mala beads at the same time, helps to block out distracting thoughts. Western scientists are beginning to discover that the chanting of mantras has health benefits and helps to calm the mind and nervous system. The word ‘mantra’ can be broken down into two parts: ‘man’, which means mind, and ‘tra’, which means transport or vehicle. In other words, a mantra is an instrument of the mind—a powerful sound or vibration that you can use to enter a deep state of meditation. -

Sawani Shende-Sathaye

SAWANI SHENDE-SATHAYE Footprints:- Sawani is born in a musically rich family. She was introduced to Indian Classical Music at a tender age of only six by her grandmother, Smt.Kusum Shende , herself a noted singer of the Kirana Gharana and an honoured artist of the Sangeet Natak Era. Sawani’s father, Dr.Sanjeev Shende, a disciple of Smt.Shobha Gurtu, has groomed her in semi classical genres like Thumri, Dadra, Kajri, etc. Quest for more and more knowledge in music brought Sawani to learn more music under the expert guidance of Dr. Smt.Veena Sahasrabuddhe, a noted classical vocalist from Gwalior Gharana. Debut:- Sawani made her first debut at the age of 10 to celebrate her grandmother’s 61st birthday. The journey of concerts started when Sawani was invited to perform at the prestigious Pt.Vishnu Digambar Jayanti Samaroh in Delhi when she was just 13. On the same day, in the evevning, Sawani was honoured when she performed for the then President of India, honourable,Mr.R.Venkatraman at the Rashtrapati Bhavan.Since then she has never looked back. Her Gurus:- Smt. Kusum Shende. Dr.Sanjeev Shende Dr.Veena Sahasrabuddhe. Her Music:- Sawani’s music is a beautiful soul searching combination of the Kirana and the Gwalior Gharana, where she mesmerizes audiences with enchanting melody and strength of both. Sawani’s confidence and mastery in Khayals, her crystal clear diction and overall sensitivity in presentation takes every performance to a very high aesthetic level. Her rendition of semi-classical genres highlights the emotive and expressive quality of Indian classical music and adds a very important dimension to her performance leaving audiences spellbound. -

Yoga and Music and Chanting

Yoga and Music and Chanting Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. “When we practice yoga asana, we [can be] easily seduced by an exclusively physical practice and all that may follow from this: obsession with youthfulness and fitness, compulsion for recognition, desire for physical perfection, a need to be the best, and a self-centeredness. As we begin to chant, longingly calling out to God, a Self-centered outlook develops; a life focused towards the Divine, towards spirit. This view brings into focus our friends, family, yoga community, neighbors and world community. We begin to desire not only a personal peace but a world peace.” —Kimberly Flynn From “Beyond Om” (cited below) NOTE: See also the “Mantra” and “Om” bibliographies. Allen, Ryan. Teacher profile: Steve Ross. LA Yoga, May/Jun 2003, pp. 11-12. Steve Ross, former professional guitarist, and teacher of Yoga for twenty years plays loud contemporary music in his asana classes. Ascent magazine. What Makes a Sound Sacred? issue. Summer 2002. See http://www.ascentmagazine.com. Balayogi, Ananda. The Yoga of Sound audiocassette. Kottakuppam, Tamil Nadu, India: International Centre for Yoga Education and Research, 1998. 90 minutes. (Carnatic vocal music with English lyrics.) Bergstrom-Nielsen, Carl. -

India Music Market Study

INDIA MUSIC MARKET STUDY Written by Sound Diplomacy CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 1.1 India at a Glance 4 General Info 4 Transport Network 5 1.2 India Geography 7 2. The Indian Recorded Music Market 9 2.1 History and Current State 9 2.2 Recorded Music Market 9 Chart Analysis 10 Piracy 11 2.3 Labels and Production Companies 11 2.4 Streaming in India 13 2.5 Record Labels, Retail and Distribution 15 Record Labels 15 Record Stores 18 Distribution 19 Booking Agencies 20 Management Companies 22 3. Live Performance Industry in India 23 3.1 Music Festivals 24 Festivals 25 3.2 Touring India 28 Venues 29 Costs of Touring 32 Tips About Touring 33 Visas 35 4. Music Publishing in India 35 4.1 Trends and Development 35 4.2 Sync and its Impact 35 4.3 Performing Rights Organisations (PRO) 36 4.4 Select Music Publishers 36 5. Music Promotion and Media 37 5.1 Radio 37 5.2 Television 38 5.3 PR (Print & Digital) 38 Select Newspapers 38 Select Music/Art Magazines 39 Select Publicists and Agencies 40 6. Business and Showcase Events 41 6.1 Select Showcases and Conferences 41 Trade shows / conferences 41 The convention was hosted and attended by some of the most influential entrepreneurs that belong to the nightlife industry. 42 7. Additional Tools and Resources 42 8. References 43 1. Introduction 1.1 India at a Glance General Info India is a federation made up of 29 states and 7 union territories. It is the second most populous country in the world, with a population of nearly 1.3 billion, and is also the seventh largest in terms of landmass.