Using Institutional Characteristics to Estimate Return on College Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

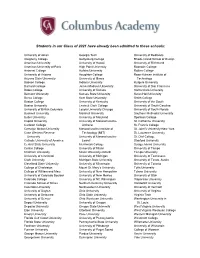

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

Scholarly Communications and the Role of the Liberal Arts College Library Diane J

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Library Faculty Research Coates Library 2013 Scholarly Communications and the Role of the Liberal Arts College Library Diane J. Graves Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/lib_faculty Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Repository Citation Graves, D.J. (2013). Scholarly communications and the role of the liberal arts college library. In P. Hernon & J.R. Matthews (Eds.), Reflecting on the future of academic and public libraries (114-119). Chicago, IL: American Library Association. This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Coates Library at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scholarly communications and the role of the liberal arts college library By Diane J. Graves University Librarian and Professor Trinity University, San Antonio TX1 A little economic history The conversation on scholarly communication (often referred to as a “crisis”) has its origins in the mid- 1980s. At that time, the balance of trade between the United States and its trading partners in Europe was so far out of balance that American products could not compete internationally. The Reagan Administration, seeking to correct the problem, devalued the dollar at the so-called Plaza Accord on September 22, 1985.i In that moment, the price of journals in many Scientific, Technical, Engineering and Medical (STEM) fields, jumped—in some cases by as much as 25%. Many of the top journals were published by British or European for-profit houses, such as Pergamon, Elsevier, Springer, Wiley, Blackwell’s, Taylor & Francis, and others. -

Muhlenberg College Five-Year Diversity Strategic Plan

Muhlenberg College Five‐Year Diversity Strategic Plan Approved by the Board of Trustees, October 24, 2014 Preamble: Terminology Throughout its work, members of the Diversity Strategic Planning Committee (DSPC) wrestled with the problem of appropriate terminology in discussing Muhlenberg's diversity aspirations. While acknowledging that many types of diversity are important and beneficial, in reviewing the revised and updated Muhlenberg College Statement on Diversity (see Appendix C) we agreed that this plan should focus on those types of diversity represented by "historically underrepresented and marginalized groups" within our community. Having said that, we found that other terms, however imperfect they may be, are occasionally useful, accurate, and necessary. The term "multicultural," for example, while inapt for describing individuals, has gained acceptance at Muhlenberg as a general term for many of the groups we understand as "historically underrepresented and marginalized" at the College. The Multicultural Center is now a hub of activity for students of color, international students, Queer students, feminist students, and others. In considering alternatives to "multicultural" in use on other campuses, we found other options equally problematic. In certain contexts the term "students of color" or "faculty/staff of color" are used when the underlying data specifically reference racial diversity. Introduction Muhlenberg College’s Diversity Strategic Planning Committee (DSPC) was convened in April, 2013 by President Helm in response -

Lafayette College: Staying Ahead of the Game

Vol. 15 LAFAYETTE COLLEGE: STAYING AHEAD OF THE GAME Lafayette College’s football history is as rich as it is varied, from laying claim to the the first use of the helmet in 1896, to the long standing rivalry with nearby Lehigh University dating back to 1884. But these days, it is the Leopards’ future that has taken on even greater importance. With the opening of the Bourger Varsity Football House, Lafayette’s team has entered into a league all its own. The 24,000 square-foot building, part of a $23 million stadium renovation, contains the team’s locker room, strength and conditioning areas, and sports medicine facilities, including a hydrother- apy room. The upper level houses coaches’ offices, each with a flat screen display for reviewing games, several meeting rooms equipped with custom control systems and full presentation capabilities, and one room large enough to accommodate the entire team. That area, which can also be divided into four separate units, features the same level of class- room technology found across the campus. “The experience we have with our smart classroom tech- nology allowed us to easily adapt to this rather unique setting with great results, ” stated E.J. Hudock, Academic Technology Facilities Manager for Lafayette. One of the very special features of the Bourger Varsity Football House is the highly personalized conference room on the second floor. The program- ming team at Vistacom worked with Lafayette to develop special graphic elements for the control system interface such as helmets for source buttons and a log in system utilizing the jersey numbers which are displayed on top of a Leopard’s jersey graphic. -

Bucknell University Student Handbook 2019-20

Bucknell University IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY, PLEASE CONTACT: BUCKNELL PUBLIC SAFETY (24 HRS) STUDENT 570-577-1111 570-577-3333 (non-emergency) For personal emergencies, please contact Public Safety and request to speak with a Student Affairs staff on-call member. HANDBOOK If you have had an unwanted sexual experience or have questions about 2019-20 something that has happened to you or a friend, please call: BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY THE ADVOCATES (24 HRS) 570-850-6115 For more information: bucknell.edu/SexualMisconduct STUDENT HANDBOOK ADDITIONAL ON-CAMPUS RESOURCES Bucknell Student Health 570-577-1401 Counseling & Student Development Center 570-577-1604 Office of the Dean of Students 570-577-1601 Title IX Coordinator 570-577-1554 2019-20 OFF-CAMPUS RESOURCES Local police or ambulance (24 hrs) 911 Transitions (24 hrs) local crisis center 800-850-7948 Evangelical Community Hospital (24 hrs) 570-522-2000 bucknell.edu One Dent Drive Lewisburg, Pa. 17837 Revised 10/2019 BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-2020 This Student Handbook is an official publication of the Office of the Dean of Students. The policies of Bucknell University are under continual examination and revision. This Student Handbook is not a contract; it merely presents the policies in effect at the time of publication and in no way guarantees that the policies will not change. For the most up-to-date policies and information, please check the link at www.bucknell.edu/StudentHandbook. The University reserves the right to modify the requirements for admission and graduation, to amend any regulation affecting the student body, and to dismiss from the University any student if it is deemed by the University to be in its best interest or in the best interest of the student to do so. -

Schools That Meet 100% of Financial Need

Schools That Meet 100% of Financial Need By Lynn O’Shaughnessy TheCollegeSolution.com While there are nearly 2,800 four-year colleges and universities in the United States, there are less than six dozen that claim that they meet 100% of the demonstrated financial need of all or most of their students. The list below includes the names of those schools. I’ve also included institutions on this list that say that they meet at least 93% of financial need or higher. Those are the bold- faced institutions. You need to keep in mind that the institutions self report these figures. A school’s gener- osity will depend heavily on the institutional aid formula that it uses. For instance, Boston College says it meet 100% of need, but its aid formula calculates the full value of a family’s home equity. It also takes a much closer look at a family’s finances than some of the other schools you’ll see below. Consequently, even schools that are similarly priced could offer significantly different packages. For example, the average need-based aid package for Boston College students is $32,146. Compare that to Amherst College’s average aid package of $47,553. WHAT DOES MEETING 100% OF FINANCIAL NEED MEAN? I often find that parents are confused by what this term —meeting 100% of financial need—means. I hope this clears up the confusion: A school that meets 100% of need will provide an aid package that fills the gap between what a family’s Expected Family Contribution is and a school’s cost of attendance. -

Students in Our Class of 2021 Have Already Been Admitted to These Schools

Students in our Class of 2021 have already been admitted to these schools: University of Akron Georgia Tech University of Redlands Allegheny College Gettysburg College Rhode Island School of Design American University University of Hawaii University of Richmond American University of Paris High Point University Roanoke College Amherst College Hofstra University Rollins College University of Arizona Houghton College Rose-Hulman Institute of Arizona State University University of Illinois Technology Babson College Indiana University Rutgers University Barnard College James Madison University University of San Francisco Bates College University of Kansas Santa Clara University Belmont University Kansas State University Seton Hall University Berea College Kent State University Smith College Boston College University of Kentucky University of the South Boston University Lewis & Clark College University of South Carolina University of British Columbia Loyola University Chicago University of South Florida Bucknell University Marshall University Southern Methodist University Butler University University of Maryland Spelman College Capital University University of Massachusetts- St. Catherine University Carleton College Amherst St. Francis College Carnegie Mellon University Massachusetts Institute of St. John’s University-New York Case Western Reserve Technology (MIT) St. Lawrence University University University of Massachusetts- St. Olaf College Catholic University of America Lowell Stanford University Central State University Merrimack College -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Nulldfr 2014 Report

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 7,500 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. IPEDS collects institution-level data on student enrollment, graduation rates, student charges, program completions, faculty, staff, and finances. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (http://collegenavigator.ed.gov), an online tool to aid in the college search process. For more information about IPEDS, see http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? As suggested by the IPEDS Technical Review Panel, the figures in this report provide selected indicators for your institution and a comparison group of institutions. The figures are based on data collected during the 2013-14 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. This report provides a list of pre-selected comparison group institutions and the criteria used for their selection. Additional information about these indicators and the pre- selected comparison group are provided in the Methodological Notes at the end of the report. -

Elite Colleges Or Colleges for the Elite?: a Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'brien Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-22-2011 Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'Brien Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Margaret Lee, "Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege" (2011). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 129. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elite Colleges or Colleges for the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege By Margaret O'Brien Submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors Requirements For the Dickinson College Department of Sociology Professor Steinbugler, Advisor Professor Schubert, Reader Professor Love, Reader 16 May 2011 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ~----------------------~2 2. Literature Review 4 3. Methodology 20 4. Data Analysis 29 5. Conclusion 48 6. Acknowledgements 52 7. Appendix A (Interview Recruitment Flier) 53 8. Appendix B (Interview Recruitment Email) 54 9. References 55 1 Studying privileged people is important because they create the ladders that others must climb to move up in the world. Nowhere is this more true than in schools, which have been official ladders of mobility and opportunity in U.S. society for hundreds of years. Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class The college experience is often portrayed as a carefree four years filled with new experiences, lifelong friendships, parties, papers and the ease of a semi-sheltered, yet independent, life. -

Opening Set for 2002 Uring the May Lumni Memorial D18 Trustee-Fac- Gymnasium Is Ulty Dinner, Alan W

Psychology_2001.qxd 5/9/03 2:13 PM Page 1 PSYCHOLOGY LAFAYETTE COLLEGE SUMMER 2001 ■ Vol.6 CHILDS WINS JAMES P. CRAWFORD AWARD Opening Set for 2002 uring the May lumni Memorial D18 trustee-fac- Gymnasium is ulty dinner, Alan W. currently being Childs, associate transformed into professor, received the Aa state-of-the-art home for James P. Crawford Lafayette’s programs in psy- Award for his out- chology and neuroscience. standing ability in The new facility will pro- classroom instruction. vide 45,000 square feet of Childs is known for his ability space on five levels including to lead classroom discussions, par- teaching laboratories, faculty ticularly in his First-Year Seminar research laboratories, shared “Human Aggression and Social faculty- student research lab- Pathology,” and his Values and oratories, and faculty offices. Science/Technology Seminar “Patient- Completion is expected to be Practitioner Interaction: The Role of sometime in 2002. Medical Technology,” noted Provost Members of the depart- June Schlueter in her remarks. ment were involved in “It was an honor to have been reviewing the plans and given an award named after some- meeting with the architects one whose career at the college I as the space was designed. have greatly admired,” says Childs. They provided advice based In a department of excellent teach- on experience in the current An architectural rendering of psychology’s new home. ers, it is a little embarrassing to be location and on exploring singled out in this way, and I think psychology facilities at other colleges. Some features include an animal of it as a compliment to the depart- research area on the lower level, common meeting spaces off the entryway ment as much as to me. -

2009-2010 (Pdf)

MUHLENBERG C O L L E G E Source Book 2009-2010 Source Book 2009-2010 • Edited By: Nicole Hammel • Director, Institutional Research & Records • Published October 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2009-2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE COLLEGE 4 I. Description 4 1. A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE COLLEGE ............................................................................................. 4 2. MISSION STATEMENT OF THE COLLEGE ...............................................................................................5 3. DIVERSITY STATEMENT OF THE COLLEGE…………………………………………………………...5 4. THE YEAR IN REVIEW, 2008-2009 ............................................................................................................. 6 5. CENTERS AND INSTITUTES .................................................................................................................... .7 6. PROGRAMS OF STUDY ............................................................................................................................. .8 7. SPECIAL ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ............................................................................................................ 9 8. DEPARTMENTAL MAJOR PROGRAMS ...................................................................................................11 9. THE WESCOE SCHOOL OF MUHLENBERG COLLEGE......………………………………………….. 15 II. Facilities 16 1. MAJOR FACILITIES ....................................................................................................................................16 2. MUHLENBERG COLLEGE PROPERTIES