Te P Ii L ¡Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report July 2018 Food Retail Report Mexico 2018Washington, D.C. Mexico City Monterrey Overview of the Mexican Food Retail Industry • The Mexican food retail industry consists in the distribution and sale of products to third parties; it also generates income from developing and leasing the real estate where its stores are located • Stores are ranked according to size (e.g. megamarkets, hypermarkets, supermarkets, clubs, warehouses, and other) • According to ANTAD (National Association of Food Retail and Department Stores by its Spanish acronym), there are 34 supermarket chains with 5,567 stores and 15 million sq. mts. of sales floor in Mexico • Estimates industry size (as of 2017) of MXN$872 billion • Industry is expected to grow 8% during 2018 with an expected investment of US$3.1 billion • ANTAD members approximately invested US$2.6 billion and created 418,187 jobs in 2017 • 7 states account for 50% of supermarket stores: Estado de Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Mexico City, Jalisco, Baja California, Sonora and Sinaloa • Key players in the industry include, Wal-Mart de Mexico, Soriana, Chedraui and La Comer. Other regional competitors include, Casa Ley, Merza, Calimax, Alsuper, HEB and others • Wal-Mart de México has 5.8 million of m² of sales floor, Soriana 4.3 m², Chedraui 1.2 m² and La Cómer 0.2 m² • Wal-Mart de México has a sales CAGR (2013-2017) of 8.73%, Soriana 9.98% and Chedraui 9.26% • Wal-Mart de México has a stores growth CAGR (2013-2017) of 3.30%, Soriana 5.75% and Chedraui 5.82% Number -

Grupo Comercial Chedraui, S.A.B. De C.V

GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. Av. Constituyentes No. 1150, Lomas Altas Delegación Miguel Hidalgo C.P. 11950 México, D. F. www.chedraui.com.mx Características de las acciones representativas del capital social de GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. Nominativas Sin valor nominal Íntegramente suscritas y pagadas Serie B Clase I Capital mínimo fijo sin derecho a retiro. Clave de Cotización en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V.: CHDRAUI Los valores emitidos por Grupo Comercial Chedraui, S.A.B. de C.V. se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores y se cotizan en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V. La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad de los valores, la solvencia de la emisora o la exactitud o veracidad de la información contenida en el reporte anual, ni convalida los actos que, en su caso, se hubieren realizado en contravención de las leyes. Reporte anual que se presenta de acuerdo con las disposiciones de carácter general aplicables a las Emisoras de valores y a otros participantes del mercado, por el año terminado el 31 de diciembre de 2015. México, D.F. a 30 de abril de 2016 ÍNDICE 1. INFORMACIÓN GENERAL ........................................................................................... 4 a) Glosario de Términos y Definiciones ......................................................................... 4 b) Resumen Ejecutivo ................................................................................................. 6 c) Factores -

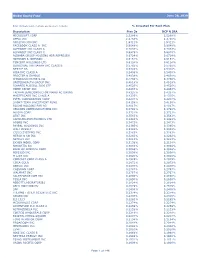

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

US-Mexico Trade Relationship

1 U.S. – Mexico Trade Relationship 2 Mexico is a growing economy Mexico has built a solid framework for macroeconomic stability in the past two decades Total Exports $374 billion $1.2 trillion economy $776 billion in total trade $457 billion in FDI attracted since 1999 125 million consumer market/ 60% middle class GDP 1.4% 2.3% 2.6% 2.3% 2013 2014 2015 2016 The 15th largest world economy 10th largest world exporter and 1st in Latin America 9th largest world importer 5th leading recipient of FDI Total Imports among emerging economies $387 billion Source: INEGI, SE-DGIE (Sep. 2016), WTO, UNCTAD, Brookings Institution, SHCP. 3 Recognizing the importance of NAFTA Trilateral trade has more than tripled, reaching nearly $1 trillion in 2016. Trilateral Trade between the NAFTA Partners 1,122 1200 1,075 1,059 1,033 1,010 997 942 1000 893 846 880 NAFTA 772 800 699 661 699 615 626 568 602 600 476 506 419 376 338 400 289 200 0 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Mexico-Canada Trade U.S.-Canada Trade Mexico-U.S. Trade Source: SE with import data from Statistics Canada, Banxico, and USDOC, and World Bank. 4 Since NAFTA, U.S.-Mexico trade has multiplied by six a million dollar a minute business Mexico is the U.S.’ third-largest trading partner $1.5 billion dollars in products are bilaterally traded each day U.S.-Mexico Trade 506 534 531 494 525 500 461 392 400 NAFTA 367 348 332 278 280 294 296 294 290 305 263 300 267 247 235 230 233 231 216 197 198 211 173 177 Billion 200 157 170 131 136 156 $ 131 134 138 108 82 101 110 226 86 95 240 236 231 100 198 217 74 163 50 62 134 137 152 129 40 111 102 111 120 71 79 87 97 97 42 51 46 57 0 199319941995199619971998199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013201420152016 US Exports to Mexico US Imports from Mexico Source: USDOC. -

Elektra (ELEKTRA) Marcela Martínez Suárez [email protected] (52-55) 5169-9384

Second Quarter 2004 Grupo Elektra (ELEKTRA) Marcela Martínez Suárez [email protected] (52-55) 5169-9384 August 5, 2004 SELL ELEKTRA * / EKT Grupo Elektra Prepays 2008 Senior Notes – Strong Price: Mx / ADR Ps 68.25 US$ 22.98 Performance at All Divisions Price Target Ps 71.00 Risk Level High • Elektra is now consolidating the Bank's results. Our comments are based on figures presented by Grupo 52 Week Range: Ps 77.20 to Ps 31.65 Elektra. During 2Q04, sales were up 20.5%, as a result of Shares Outstanding: 236.7 million strong performance at the Bank and the retail division. Market Capitalization: US$ 1.41 billion New personnel hired resulted in an 0.8-pp contraction in Enterprise Value: US$ 2.04 billion operating margin. Operating profit and EBITDA, Avg. Daily Trading Value US$ 1.4 million however, were up 12.5% and 11%, respectively. Retail Ps/share US$/ADR store formats are posting strong results, and the "Nobody 2Q EPS 1.39 0.49 Undersells Elektra" slogan has attracted more consumers. T12 EPS 6.19 2.16 The group's valuation, as measured by the EV/EBITDA T12 EBITDA 15.55 5.42 multiple, is at 6.35x, and should drop to 5.8x by year-end T12 Net Cash Earnings 11.93 4.16 2004. Our price target of Ps 71 represents a 5.54% Book Value 28.86 10.06 nominal yield, including a Ps 1.033 dividend. The above, T12 2004e coupled with the fact that Elektra is a high-risk stock, P/E 11.02x leads us to recommend Elektra as a SELL. -

Actualización Conjunta De Nuestro Universo De Cobertura

Actualización conjunta de nuestro universo de cobertura Mercado accionario Análisis fundamental en medio de la pandemia colombiano Dirección de Investigaciones Económicas, Sectoriales y de Mercados Julio de 2020 Análisis fundamental en medio de la pandemia 47% sobreponderar, 5% Neutral, 37% subponderar y 11% Bajo Revisión La incertidumbre y el miedo hacen una mezcla explosiva para los mercados financieros, generando descalces de valor como los que, en nuestra opinión, vivimos en la actualidad. Esta sobrerreacción a las noticias económicas negativas en medio del pánico (covid-19) es normal en el corto plazo, abriendo oportunidades de inversión desde un punto de vista fundamental para portafolios que quieran apostarle a la recuperación económica. Actualizamos nuestro universo de cobertura realizando diferentes ajustes a nuestra metodología de valoración, entre las que destacamos ajustes en la tasa de descuento, expectativas de crecimiento en los diferentes sectores económicos, al igual que nuevas proyecciones macroeconómicas para Colombia y los países de la región. Con base en lo anterior, concluimos que el mercado colombiano presenta un atractivo descuento fundamental, con un índice COLCAP que presenta un potencial de valorización del 38,9%. Es importante tener presente que ninguna compañía nos arroja un potencial de valorización negativo, en otras palabras, la recomendación de Subponderar obedece a que dichos activos rentarán un 5% menos que la expectativa fundamental del índice Colcap Nunca antes el trabajo de un analista fundamental había sido tan complejo, pues las compañías de cara a la coyuntura han dejado de dar su visión de expectativa de resultados para 2020, lo que incrementa el nivel de riesgo de nuestras recomendaciones. -

T E P N L R E V I E W

T e p n L R e v i e w , NUMBER 65 AUGUST 1998 SANTIAGO, CHILE OSCAR ALTIMIR Director o f the Review EUGENIO LAHERA Technical Secretary Notes and explanation of symbols The following symbols are used in tables in the Review: (...) Three dots indicate that data are not available or are not separately reported. (-) A dash indicates that the amount is nil or negligible. A blank space in a table means that the item in question is not applicable. (-) A minus sign indicates a deficit or decrease, unless otherwise specified. (■) A point is used to indicate decimals. (/) A slash indicates a crop year or fiscal year, e.g., 1970/1971. (-) Use of a hyphen between years, e.g., 1971-1973, indicates reference to the complete number of calendar years involved, including the beginning and end years. References to “tons” mean metric tons, and to “dollars”, United States dollars, unless otherwise stated. Unless otherwise stated, references to annual rates of growth or variation signify compound annual rates. Individual figures and percentages in tables do not necessarily add up to the corresponding totals, because of rounding. Guidelines for contributors to CEPAL Review The editorial board of the Review are always interested in encouraging the publication of articles which analyse the economic and social development of Latin America and the Caribbean. With this in mind, and in order to facilitate the presentation, consideration and publication of papers, they have prepared the following information and suggestions to serve as a guide to future contributors. —The submission of an article assumes an undertaking by the author not to submit it simultaneously to other periodical publications. -

Chapter 3: Business for Development

Chapter 3: Business for Development Multinationals, telecommunications and development Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows have stepped up dramatically around the world since the mid-1980s. In Latin America, the 1990s were a period of accelerated FDI inflows, led by the entry of developed-country multinationals into newly privatised or liberalized sectors. The real change, however, is not in the game but in the players. Of worldwide FDI stocks, the share emanating from developing countries has increased by half, growing from 8 per cent in 1990 to 12 per cent in 2005. Latin American enterprises now also play away from home. Since 2006, the value of annual outward FDI flows from the major countries in the region has flirted with the $40 billion mark. This explosion of outward investment is largely the result of the rapid internationalisation of a small number of large enterprises, mainly from Brazil and Mexico. Indeed, in 2006, Brazil was a net source of FDI, with outward flows amounting to $26 billion, as compared to inflows of $18 billion. The largest Latin American multinationals are in primary commodities and related activities; Mexico’s cement producer, CEMEX, and Brazil’s Petrobras, in oil, and Companhia Vale do Río Doce (CVRD), in mining, are important examples. Services and final goods have also become key areas of multinational activity by Latin American firms, first regionally, and now, for a small number of very successful enterprises, globally. While these firms’ multinational growth reflects diverse corporate strategies, scopes and ambitions, it places Latin America firmly on the new global map of home countries for multinational corporate activity. -

Foreign Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean

(FRQRPLF&RPPLVVLRQIRU/DWLQ$PHULFDDQGWKH&DULEEHDQ (&/$& )RUHLJQ,QYHVWPHQWLQ/DWLQ$PHULFDDQGWKH&DULEEHDQLVWKHODWHVWHGLWLRQRIDVHULHVSXEOLVKHGDQQXDOO\E\WKH 8QLWRQ,QYHVWPHQWDQG&RUSRUDWH6WUDWHJLHVRIWKH(&/$&'LYLVLRQRI3URGXFWLRQ3URGXFWLYLW\DQG0DQDJHPHQW ,WZDVSUHSDUHGE\ÈOYDUR&DOGHUyQ3DEOR&DUYDOOR0LFKDHO0RUWLPRUHDQG0iUFLD7DYDUHVZLWKWKHDVVLVWDQFHRI $GULDQ1\JDDUG/HPD1LFRODV&KDKLQH3KLOOLS0OOHU$OLVRQ&ROZHOO%U\DQW,YHVDQG&DUO1LVV)DKODQGHQDQG FRQWULEXWLRQVIURPWKHFRQVXOWDQWV*HUPDQR0HQGHVGH3DXOD*XVWDYR%DUXM'DYLG7UDYHVVR&HOVR*DUULGR3DWULFLR <ixH]DQG1LFROR*OLJR&KDSWHU9ZDVSUHSDUHGMRLQWO\E\WKH8QLWRQ,QYHVWPHQWDQG&RUSRUDWH6WUDWHJLHVDQGWKH $JULFXOWXUDO'HYHORSPHQW8QLWERWKSDUWRIWKH&RPPLVVLRQ¶V'LYLVLRQRI3URGXFWLRQ3URGXFWLYLW\DQG0DQDJHPHQW ,QSXWVIRUWKLVFKDSWHUZHUHSURYLGHGE\WKHFRQVXOWDQWV0DUF6FKHLQPDQDQG-RKQ:LONLQVRQDPRQJRWKHUVLQWKH IUDPHZRUNRIWKHSURMHFWHQWLWOHG³$JULFXOWXUDOGHYHORSPHQWSROLFLHVDQGWUDQVQDWLRQDOFRUSRUDWLRQV¶VWUDWHJLHVLQWKH DJULIRRGVHFWRU´RIWKH*RYHUQPHQWRIWKH1HWKHUODQGV,QWKLVUHJDUGWKHFRQWULEXWLRQVRI0{QLFD5RGULJXHVDQG 6RItD$VWHWH0LOOHUDUHJUDWHIXOO\DFNQRZOHGJHG7KDQNVDUHDOVRGXHWRWKHFRUSRUDWHH[HFXWLYHVZKRDJUHHGWRWDNH SDUWLQWKHLQWHUYLHZVFRQGXFWHGGXULQJWKHSUHSDUDWLRQRIFKDSWHUV,,,WR9, 7KHLQIRUPDWLRQXVHGLQWKLVUHSRUWKDVEHHQGUDZQIURPDQXPEHURILQWHUQDWLRQDODJHQFLHVLQFOXGLQJWKH,QWHUQDWLRQDO 0RQHWDU\)XQGWKH8QLWHG1DWLRQV&RQIHUHQFHRQ7UDGHDQG'HYHORSPHQWDQGWKH2UJDQLVDWLRQIRU(FRQRPLF&R RSHUDWLRQDQG'HYHORSPHQWDVZHOODVDKRVWRIQDWLRQDOLQVWLWXWLRQVVXFKDVFHQWUDOEDQNVDQGLQYHVWPHQWSURPRWLRQ DJHQFLHVLQ/DWLQ$PHULFDDQGWKH&DULEEHDQDQGVSHFLDOL]HGSUHVV$FUXFLDOLQSXWIRUWKLVUHSRUW±±WKHGDWDUHODWLQJ -

Program Brochure a Cement and Lime Industry Conference and Exhibition By

18 PROGRAM BROCHURE A CEMENT AND LIME INDUSTRY CONFERENCE AND EXHIBITION BY CONTACT SALES / SPEAKING SPONSORSHIPS OPPORTUNITIES Ali Assad Magda Kwapisiewicz [email protected] [email protected] 2020 +40 754 023 330 +351 939 114 543 Bianca Elliff MAY 28-29, 2020 • SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL [email protected] +351 911 074 128 PAST PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES PAST PARTICIPATING COMPANIES A TEC GRECO • A Tec Production &Services • AAF Brasil • ABIMAQ • ABRAMAT • ALL MINMETAL INTL. • Allfran • Alstom • American Air Filter Brasil • ArcelorMittal • Argos Colombia • Argus • Associação • Brasileira de Cerâmica • Association Brasil de Cimento Portland • Assuncao Representacoes • Aumund • Austrian Government • Autochartering • Bahamut • Banco Inercorp • BASF • Bedeschi SPA • Benue Cement • Beumer • Boldrocchi • Brazil Steel Institute • BRC Cimentos • Brennand Cimentos • Brennand Energia • Bruker do Brasil • BWF Envirotec • Cal & Cemento Sur S.A. • CALCO-BOLIVIA • Camargo Correa • Carmeuse Lime & Stone • CCB- • Cimpor Cimentos de Brasil • Cemengal • Cementos Argos • Cementos Avellaneda • Cementos Fortaleza • Cementos Melon • Cementos Progresso • Cemex • CEMI • Christian Pfeiffer Maschinenfabrik GmbH • Cia de Cimento Itambé • CIMAR – Cimentos do Maranhão • Cimento Apodi • Cimento Bravo • Cimento Nacional • Cimento Nassau • Cimento Planazto • Cimento Tupi • Cimentos da Bahia S.A. • Cimentos Liz • CIMERWA • Cimpor • Cimprogetti • Cimento Planalto • Ciplan Cemento • Clanap • Claudius Peters • CMLG System Process Engineering • Companhia Industrial de Cimento Apodi • Companhia -

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767% -

CEMEX Perspectivas Más Favorables Y Valuación Atractiva @Analisis Fundam

Análisis y Estrategia Bursátil México Reporte Trimestral 29 de julio 2021 CEMEX www.banorte.com Perspectivas más favorables y valuación atractiva @analisis_fundam ▪ Las cifras de CEMEX del 2T21 mostraron sólidos avances, por arriba de nuestras estimaciones, y una expansión en rentabilidad, superando José Espitia Subdirector Análisis Bursátil los niveles pre-pandemia. Destacó la mayor generación de FCF [email protected] ▪ El indicador de apalancamiento ya se colocó en un nivel de estructura de capital de grado de inversión. Aumentamos nuestras proyecciones COMPRA Precio Actual $16.76 ante perspectivas más favorables comunicadas en el CEMEX Day PO $22.50 Rendimiento Potencial 34.2% ▪ Subimos el PO a $22.50 vs. 19.50 -FV/EBITDA 2021e 8.3x vs. 8.8x del Precio ADR US$8.40 PO ADR US$11.14 sector. Reiteramos la visión positiva para la cementera, que forma Acciones por ADR 10 parte de nuestra selección de emisoras beneficiadas por el entorno Máx – Mín 12m (P$) 17.88 – 6.6 Valor de Mercado (US$m) 12,378.3 Acciones circulación (m) 14,708 Continúan los fuertes crecimientos ante el mejor desempeño de mercado y Flotante 90% eficiencias operativas. Los números del 2T21 se vieron apoyados por un buen Operatividad Diaria (P$ m) 445 .8 Múltiplos 12m comportamiento de la demanda y un entorno favorable de precios, además de la FV/EBITDA 7.4x baja base comparativa (la mayor afectación del COVID-19 se dio en el 2T20). P/U -23.3x MSCI ESG Rating* BBB En todas las regiones hubo dinámicas favorables aunque destacaron México y Europa, Medio Oriente África y Asia.