UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Summer Traditions 2020 Tour

SLIGHTLY STOOPID SUMMER TRADITIONS 2020 TOUR BAND REVEALS FIRST ROUND OF SUMMER SHOWS, INCLUDING TWO NIGHTS AT RED ROCKS AMPHITHEATER ADDITIONAL DATES STILL TO BE ANNOUNCED TICKETS ON SALE FRIDAY, MARCH 13 March 9, 2020 (San Diego, CA) - Today, Billboard chart-toppers Slightly Stoopid unveil the first round of dates for their annual summer tour. Dubbed Summer Traditions 2020 (a nod to the outdoor summer tour-circuit the band has done annually since 2006), Slightly Stoopid and fans alike will travel the states, sharing good times with one another through music and community as they have done since the band’s inception 25 years ago. This 2020 edition of Slightly Stoopid’s summer amphitheater tour kicks off in Eugene, OR on June 11th, 2020 and routes the beloved So-Cal band throughout North America, including two nights at the legendary Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Morrison, CO on August 15-16, 2020. Joining Slightly Stoopid for their Summer Traditions 2020 tour are special guests Pepper, Common Kings, and Don Carlos. All currently announced dates are listed below, with additional dates to be announced soon. Fans gain first access to the artist presale beginning Tuesday, March 10th at 10 AM local at www.slightlystoopid.com. The local presale will run from 10 AM - 10 PM local time on Thursday, March 12th, and the general public on-sale will then take place on Friday, March 13th at 10 AM local time. Formed in the mid-90’s by founding members Miles Doughty and Kyle McDonald, Slightly Stoopid has steadily risen to the top - always fostering their dedicated fanbase. -

Pressrelease 2010 Hangout Waterkeeper

TENNESSEE RIVERKEEPER Press Release (May 13, 2010) – ## For Immediate Release Leading environmental activists band together at The Hangout Beach Music and Arts Festival (May 14th - 16th) in Gulf Shores, Ala to raise awareness for the inhabitants and habitats affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf Coast. The Hangout Beach, Music and Arts Festival has announced that environmental activists Erin Brockovich, Kathleen "Kick" Kennedy, David Whiteside, and Sierra Club Board President Allison Chin will participate in on-stage announcements, public panel discussion and press conferences about BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil disaster and the Waterkeeper Alliance and it’s affiliated organizations along the Gulf Coast and in Alabama. On-stage announcements from some of the nation’s top environmental leaders will take place throughout the weekend. The press conferences at the festival will occur on Saturday, May 15 at 3pm and the public panel discussion on Sunday, May 16 at 2:30pm. Additionally, various local Waterkeeper organizations will host an outreach table on the festival grounds, which will contain info about the Waterkeepers and will be managed by staff members and volunteers. As previously announced, all profits from The Hangout will be donated to Gulf Coast restoration and relief efforts. Many musicians who will be performing at The Hangout Beach Music and Arts Festival have starred in Riverkeeper promotional videos that were produced by David Whiteside of Alabama, Founder of Black Warrior Riverkeeper and Tennessee Riverkeeper and former MTV News correspondent. Musicians including Questlove from The Roots, Michael Franti and Spearhead, Ozomatli, Phish, and The Flaming Lips (cancelled), have appeared in public service announcement videos for Riverkeeper organizations in Alabama. -

The Collector Auction

THE COLLECTOR AUCTION 6.00pm6:00pm – Thursday - 15th 24 Augustth July, 2014 2019 Viewing: Wed.10am – 6pm & Thurs.12pm – 6pm 25 Melbourne Street, Murrumbeena, Vic. 3163 Tel: 03 9568 7811 & 22 Fax: 03 9568 7866 Email: [email protected] BIDS accepted by phone, fax or email. Phone bids accepted for items over $100 only. NOT ACCEPTED after 5.30pm on day of sale Please submit absentee bids in increments of $5 Photos emailed on request - time permitting Payment by Credit card, Cheque, Money Order or Cash Please pay for and collect goods by Friday 5pm following auction 22% buyer premium + GST applies! 1.1% charge on Credit Card and EFTPOS AUCTIONS HELD EVERY THURSDAY EVENING 6.00pm AUCTIONEER – ADAM TRUSCOTT Lot No Description 1 Large Wooden Framed Shaped Mirror 2 C1900 Chaise lounge with upholstered rail to back with deep pink floral upholstery 2.1 19th C gilt framed British School watercolour - Street Vendor, no signature sighted, 49cm H 42cm L 3 3 x Framed Watercolour Portraits Signed Stan Sly 4 Circa 1900 wooden Cedar swing vanity mirror with curved top and lidded compartment, approx 64cm H. 5 Circa 1916 Narragansett Machine Co Providence R.I metal Spirometer machine for measuring lung capacity (a/f) 6 Group lot mainly vintage jewellery - 1920s enamel buckle, bone necklace, diamante bracelet, brooches, chain, m.o.p. pendant, Geo. VI Coronation medallion, mini souvenir Eiffel Tower views booklet pendant etc. 7 Small Group of Bone Handled writing Utensils & Ebonized Parallel Ruler 8 Taxidermy Adolescent Crocodile - approx 51 cm long 9 Small box lot mainly vintage costume jewellery incl. -

Marx, Windows Into the Soul: Surveillance and Popular Culture, Chapter A

Marx, Windows Into the Soul: Surveillance and Popular Culture, Chapter A Culture and Contexts (intro from printed book) News stories don’t satisfy on a human level. We know that Guantanamo is still open, but do we really know what that means?’ The idea is to experience an emotional understanding, so it’s not just an intellectual abstraction. -Laura Poitras, filmmaker The structure, process and narrative units that make up most of the book rely on language in presenting facts and argument. In contrast, the emphasis in this unit is on forms of artistic expression. .Images and music are one component of the culture of surveillance that so infuses our minds and everyday life. The symbolic materials and meanings of culture are social fabrications (though not necessarily social deceptions). They speak to (and may be intended to create or manipulate) needs, aspirations, and fears. Culture communicates meaning and can express (as well as shape) the shared concerns of a given time period and place. Surveillance technology is not simply applied; it is also experienced by agents, subjects, and audiences who define, judge and have feelings about being watched or a watcher. Our ideas and feelings about surveillance are somewhat independent of the technology per se. As with the devil in Spanish literary tradition (image below) the artist can serve to take the lid off of what is hidden, revealing deeper meanings. Here the artist acts in parallel to the detective and the whistleblower: Marx, Windows Into the Soul: Surveillance and Popular Culture, Chapter A In the original version of the book I divided the cultural materials into two units. -

Conceptions of Authenticity in Fashion Blogging

“They're really profound women, they're entrepreneurs”: Conceptions of Authenticity in Fashion Blogging Alice E. Marwick Department of Communication & Media Studies Fordham University Bronx, New York, USA [email protected] Abstract Repeller and Tavi Gevinson of Style Rookie, are courted by Fashion blogging is an international subculture comprised designers and receive invitations to fashion shows, free primarily of young women who post photographs of clothes, and opportunities to collaborate with fashion themselves and their possessions, comment on clothes and brands. Magazines like Lucky and Elle feature fashion fashion, and use self-branding techniques to promote spreads inspired by and starring fashion bloggers. The themselves and their blogs. Drawing from ethnographic interviews with 30 participants, I examine how fashion bloggers behind The Sartorialist, What I Wore, and bloggers use “authenticity” as an organizing principle to Facehunter have published books of their photographs and differentiate “good” fashion blogs from “bad” fashion blogs. commentary. As the benefits accruing to successful fashion “Authenticity” is positioned as an invaluable, yet ineffable bloggers mount, more women—fashion bloggers are quality which differentiates fashion blogging from its overwhelmingly female—are starting fashion blogs. There mainstream media counterparts, like fashion magazines and runway shows, in two ways. First, authenticity describes a are fashion bloggers in virtually every city in the United set of affective relations between bloggers and their readers. States, and fashion bloggers hold meetups and “tweet ups” Second, despite previous studies which have positioned in cities around the world. “authenticity” as antithetical to branding and commodification, fashion bloggers see authenticity and Fashion bloggers and their readers often consider blogs commercial interests as potentially, but not necessarily, to be more authentic, individualistic, and independent than consistent. -

Izona S Art: First Album to Be Like a Jackson 5 Thing in the Audience's Eyes That Album (Straight up Pop Without Just Makes the Shows Fun

For the week of Aug. Sept. 10-16 The Lumberjack Happenings A G pseo f Goldfinger Mon. - Thurs. - 5:15, 7:40 H ar kin v Flagstaff I uxurv 11 gets its She’s Sc Lovefy (R) 4650 N. Highway 89 774-4700 (1:30Sat. & Sun. only), 5,7A (9 p.m. Fri. & Sat. only) > I r tyiii The Gamei R) Mon. - Thurs. - 5A 7:30 p.m. hang ups Cl I a-ih. Sat. A Sun. only),!, 2:25,4.5:20, 7,8:10 & (12:40 a.m Fri. & Sal. only). H ercules (G) Flagstaff Mall Cinema out into (10:55 Sat.A Sun. only), 4:20A 9:00 4650 N. Highway 89 52 ^4 5 5 5 Excess Baggage (PG-13) * Jeffrey Bell (10:10 SaL A Sun. only), 1:30,4:30,7:30A 10 Cop L an d (PG-13) Happenings Editor (12:35 a.m. Fri.& Sat. only) (1:45 Sat. - Mon. only), 4:30,7,9:10 & (4:30 p.m. inofifi firm Fri. & Sal. csnly ) the open H oodlum (R) Mon.- Thurs. - 4:45,7p.m. 12:45,3:50,7:20A 10:40 p.m. A ir B ud (R) Four guys from Los AngelesDoubt and the Skeletones G J . Ja n e (R) are ready togive Phoenix the finstopped by to help out. ( 10:30 Sat. A Sun. only), 1:10.4:10, 7:10, 4:45 p.m.A (2:15 Sat.A Sun. only) ger. The Goldfinger "Working with Angelo Moore 10:10 & (i 2:45 a.m. -

The Hollywood Reporter November 2015

Reese Witherspoon (right) with makeup artist Molly R. Stern Photographed by Miller Mobley on Nov. 5 at Studio 1342 in Los Angeles “ A few years ago, I was like, ‘I don’t like these lines on my face,’ and Molly goes, ‘Um, those are smile lines. Don’t feel bad about that,’ ” says Witherspoon. “She makes me feel better about how I look and how I’m changing and makes me feel like aging is beautiful.” Styling by Carol McColgin On Witherspoon: Dries Van Noten top. On Stern: m.r.s. top. Beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, today, beauty is in the eye of the Internet. This, 2015, was the year that beauty went fully social, when A-listers valued their looks according to their “likes” and one Instagram post could connect with millions of followers. Case in point: the Ali MacGraw-esque look created for Kendall Jenner (THR beauty moment No. 9) by hairstylist Jen Atkin. Jenner, 20, landed an Estee Lauder con- tract based partly on her social-media popularity (40.9 million followers on Instagram, 13.3 million on Twitter) as brands slavishly chase the Snapchat generation. Other social-media slam- dunks? Lupita Nyong’o’s fluffy donut bun at the Cannes Film Festival by hairstylist Vernon Francois (No. 2) garnered its own hashtag (“They're calling it a #fronut,” the actress said on Instagram. “I like that”); THR cover star Taraji P. Henson’s diva dyna- mism on Fox’s Empire (No. 1) spawns thousands of YouTube tutorials on how to look like Cookie Lyon; and Cara Delevingne’s 22.2 million Instagram followers just might have something do with high-end brow products flying off the shelves. -

Graphics Incognito

45 amateur, trendy, and of-the-moment. The irony, What We Do Is Secret the subject of spirited disagreement and post-hoc of course, being that over the subsequent two speculation both by budding hardcore punks decades punk and graffiti (or, more precisely, One place to begin to consider the kind of and veteran scenesters over the past twenty-five GRAPHICS hip-hop) have proven to be two of the most crossing I am talking about is with the debut years. According to most accounts, ‘GI’ stands productive domains not only for graphic design, (and only) album by the legendary Los Angeles for ‘Germs Incognito’ and was not originally INCOGNITO but for popular culture at large. Meanwhile, punk band the Germs, titled simply ����.5 intended to be the title of the album. By the time Rand’s example remains a source of inspiration The Germs had formed in 1977 when teenage the songs were recorded the Germs had been by Mark Owens to scores of art directors and graphic designers friends Paul Beahm and George Ruthen began banned from most LA clubsclubs andand hadhad resortedresorted to weaned on breakbeats and powerchords. writing songs in the style of their idols David booking shows under the initials GI. Presumably And while I suppose it might be possible to see Bowie and Iggy Pop. After the broadcast of a in order to avoid confusion, the band had wanted My interest has always been in restating Rand’s use of techniques like handwriting, ripped London performance by The Clash and The Sex the self-titled LP to read ‘GERMS (GI)’, as if it the validity of those ideas which, by and paper, and collage as sharing certain formal Pistols on local television a handful of Los Angeles were one word. -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts. -

T of À1 Radio

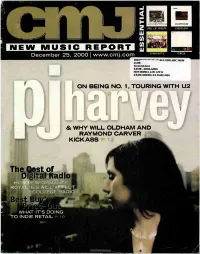

ism JOEL L.R.PHELPS EVERCLEAR ,•• ,."., !, •• P1 NEW MUSIC REPORT M Q AND NOT U CIRCLE December 25, 2000 I www.cmj.com 138.0 ******* **** ** * *ALL FOR ADC 90198 24498 Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS 5319 HONDA AVE APT G ATASCADERO, CA 93422-3428 ON BEING NO. 1, TOURING WITH U2 & WHY WILL OLDHAM AND RAYMOND CARVER KICK ASS tof à1 Radio HOW PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES WILL AFFECT COLLEGE RADIO WHAT IT'S DOING TO INDIE RETAIL INCLUDING THE BLAZING HIT SINGLE "OH NO" ALBUM IN STORES NOW EF •TARIM INEWELII KUM. G RAP at MOP«, DEAD PREZ PHARCIAHE MUNCH •GHOST FACE NOTORIOUS J11" MONEY PASTOR TROY Et MASTER HUM BIG NUMB e PRODIGY•COCOA BROVAZ HATE DOME t.Q-TIIP Et WORDS e!' le.‘111,-ZéRVIAIMPUIMTPIeliElrÓ Issue 696 • Vol 65 • No 2 Campus VVebcasting: thriving. But passion alone isn't enough 11 The Beginning Of The End? when facing the likes of Best Buy and Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office other monster chains, whose predatory ruled that FCC-licensed radio stations tactics are pricing many mom-and-pops offering their programming online are not out of business. exempt from license fees, which could open the door for record companies looking to 12 PJ Harvey: Tales From collect millions of dollars from broadcasters. The Gypsy Heart Colleges may be among the hardest hit. As she prepares to hit the road in support of her sixth and perhaps best album to date, 10 Sticker Shock Polly Jean Harvey chats with CMJ about A passion for music has kept indie music being No. -

Arts Ed Collective, CIAG, Civic Art, and OGP

Additional Prospective Panelist Names received by 10/17/2018 - Arts Ed Collective, CIAG, Civic Art, and OGP Arts Ed Colle Civic Name of Nominator Panelist Nomination Title Organization City Discipline(s) ctive CIAG Art OGP Arts Educator / Master of Arts Alma Catalan Alma Catalan in Arts Management Candidate Claremont Graduate University Los Angeles Arts Education x Los Angeles County Department Anna Whalen Anna Whalen Grants Development Manager of Education Los Angeles Arts Education x x x Anthony Carter Anthony Carter Transition Coordinator Compton YouthBuild Los Angeles Community Development, At Risk Youth x Director, Community Relations Los Angeles Literary, Theatre, Community Development, Culturally Specific Aurora Anaya-Cerda Aurora Anaya-Cerda and Outreach Levitt Pavilion Los Angeles (Westlake/MacArthur Park) Services, Education/Literacy, Libraries, Parks/Gardens x x Development & Marketing Brittany A. Gash Brittany A. Gash Manager Invertigo Dance Theatre Los Angeles Presenting, Dance x x Arts Education, Visual Arts, At Risk Youth, Traditional and Folk Dewey Tafoya Dewey Tafoya Artist Self-Help Graphics Boyle Heights, Los Angeles Arts x x Arts Education, Dance, Multidisciplinary, Theatre, Traditional and Folk Art, Visual Arts, At Risk Youth, Civil Rights/Social Justice, Community Development, Culturally Specific Services, Edmundo Rodriguez Edmundo Rodriguez Designer/Producer N/A Los Angeles Education/Literacy, Higher Education x x Arts Education, Arts Service, Dance, Multidisciplinary, Presenting, Elisa Blandford Elisa Blandford