Mieczysław Tomaszewski Listening to Penderecki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jùáb «^Å„Šma

557149 bk Penderecki 30/09/2003 11:39 am Page 16 Quando corpus morietur, While my body here decays, DDD fac, ut animae donetur make my soul thy goodness praise, Paradisi gloria. safe in paradise with thee. PENDERECKI 8.557149 From the sequence ‘Stabat Mater’ for the Feast of the Seven Dolours of Our Lady St Luke Passion ∞ Evangelist, Christ and Chorus Evangelist, Christ and Chorus Kłosiƒska • Kruszewski • Tesarowicz • Kolberger • Malanowicz • Warsaw Boys Choir Erat autem fere hora sexta, et tenebrae factae sunt And it was about the sixth hour, and there was a in universam terram usque in horam nonam. darkness over all the earth until the ninth hour. Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra Et obscuratus est sol, et velum templi scissum est And the sun was darkened, and the veil of the temple was medium. Et clamans voce magna Iesus, ait: rent in the midst. And Jesus crying with a loud voice, said: Antoni Wit “Pater, in manus Tuas commendo spiritum meum.” “Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit.” Consummatum est. “It is finished.” St Luke 23, 44-46 and St John 19, 30 ¶ Chorus and Soloists Chorus and Soloists In pulverem mortis dedixisti me. Thou hast brought me down into the dust of death… Crux fidelis… Faithful cross... Miserere, Deus meus… Have mercy, my God… In Te, Domine, speravi, In thee, O Lord, have I put my trust: non confundar in aeternum: let me never be put to confusion, in iustitia Tua libera me. deliver me in thy righteousness. Inclina ad me aurem Tuam, Bow down thine ear to me: accelera ut eruas me. -

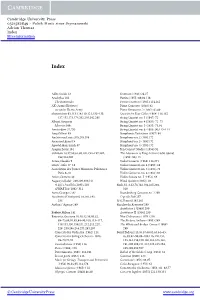

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Graå»Yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Gra#yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions: From a Perspective of Music Performance Hui-Yun (Yi-Chen) Chung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ AND HER VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS- FROM A PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE By HUI-YUN (YI-CHEN) CHUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Hui‐Yun Chung defended this treatise on November 3, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above‐named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my beloved family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Professor Eliot Chapo for his support and guidance in the completion of my treatise. I also thank my committee members, Dr. James Mathes and Professor Melanie Punter, for their time, support and collective wisdom throughout this process. I would like to give special thanks to my previous violin teacher, Andrzej Grabiec, for his encouragement and inspiration. I wish to acknowledge my great debt to Dr. John Ho and Lucy Ho, whose kindly support plays a crucial role in my graduate study. I am grateful to Shih‐Ni Sun and Ming‐Shiow Huang for their warm‐hearted help. -

Penderecki Has Enjoyed an International Reputation for Music That Blends Direct, Emotional Appeal with Contemporary Compositional Techniques

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Since 1966, with the composition of the St Luke Passion (Naxos 8.557149), Penderecki has enjoyed an international reputation for music that blends direct, emotional appeal with contemporary compositional techniques. The neo-Romantic choral work, Te Deum, was inspired by the anointing of Karol Wojtyla as the first Polish Pope in 1978. Although Penderecki’s recent choral works have tended to be similarly monumental in scale, he has written several of a more compact DDD PENDERECKI: nature, such as Hymne an den heiligen Daniel, whose opening ranks as one of the composer’s most PENDERECKI: affecting. This disc closes with two works for strings: the experimental Polymorphia from 1961, 8.557980 and the expressive Chaconne, written in 2005 as a tribute to the late Pope John Paul II. Krzysztof Playing Time PENDERECKI 67:06 (b. 1933) Te Deum Te Deum Te Te Deum (1979-80)* 36:46 Deum Te 1 Part One 13:02 2 Part Two 7:53 3 Part Three 15:51 4 Hymne an den heiligen Daniel (1997)† 12:14 www.naxos.com Made in the EU Kommentar auf Deutsch Booklet notes in English ൿ 5 Polymorphia (1961) 10:48 & 6 Polish Requiem: Chaconne (2005) 7:18 Ꭿ 2007 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Izabela Kłosi´nska, Soprano* • Agnieszka Rehlis, Mezzo-soprano* Adam Zdunikowski, Tenor* • Piotr Nowacki, Bass* Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir*† (Henryk Wojnarowski, choirmaster) Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Sung texts are available at www.naxos.com/libretti/557980.htm 8.557980 Recorded from 5th to 7th September, 2005 (tracks 1-3), and on 29th September, 2005 (track 4), 8.557980 at Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Poland Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Lupa and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 1 and 4), and Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 2 and 3) • Publisher: Schott Musik Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse • Cover image: Grey Black Cross by Sybille Yates (dreamstime.com). -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Kajetan Czubacki

Krzy ztof PEND SCENA OPEROWA Dyrektor Naczelny JERZY NOWOROL Dyrektor Artystyczny RUBEN SILVA Zastępca Dyrektora dis Administracyjno-Technicznych KAJETAN CZUBACKI Zastępca Dyrektora dis Ekonomiczno-Organizacyjnych BARBARA SUMEK-BRANDYS KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI, ur. 23 listopada 1933 w Dębicy, studio SPIS UTWORÓW KRZYSZTOFA PENDERECKIEGO wał kompozycję u Franciszka Skołyszewskiego , a następnie w Państ wowej Wyższej Szkole Muzycznej w Krakowie u Artura Malawskiego Muzyka sceniczna i Stanisława Wiechowicza. Jest laureatem wielu nagród artystycznych Diabły z Loudun. Opera w 3 aktach, libretto kompozytora według J. Whitinga i A. Huxleya (1969) Raj utracony - sacra rappresentazione w dwóch aktach, libretto Ch. Frey według krajowych i zagranicznych, w tym Nagrody Państwowej I stopnia (1968, J. Miltona (1978) Czarna Maska. Opera w I akcie, libretto kompozytora i H. Kupfera 1983), Nagrody Związku Kompozytorów Polskich (1970), Nagrody im. wedlug G. Hauptmanna (1968) Ubu Rex. Opera buffo według A. Jarry (1991) Herdera (1977), Nagrody im. Honeggera (1978), Nagrody im. Sibeliusa (1983). Premio Lorenzo Magnifico (1985), nagrody izraelskiej Fundacji Muzyka orkiestrowa im. Karla Wolfa (1987), Grammy Award (1988), Grawemeyer Award Epitaphium Artur Malawski in memorian na orkiestrę smyczkową i kotły (1958) Emanacje na dwie orkiestry smyczkowe ( 1958) (1992); doktorem honoris causa uniwersytetów w Rochester, Bordeaux, Anaklasis na orkiestrę s myczkową i perkusję (1960) Leuven, Belgradzie, Waszyngtonie, Madrycie, Poznaniu; członkiem ho Ofiarom Hiroszimy - tren na 52 instrumenty smyczkowe (1960) norowym Royal Academy of Music w Londynie, Accademia Nazionale Polymorphia na 48 instrumentów smyczkowych (1961) di Santa Cecilia w Rzymie, Kungl. Musikaliska Akademien w Sztokhol Kanon na orkiestrę smyczkową i ta ś mę magnetofonową (1962) Fluorescencje na orkiestrę symfoniczną (1962) mie, Akademie der Kiinste w Berlinie, Academia Nacionals de Bellas De Natura sonoris No. -

Persons As Self-Consciously Concerned Beings

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Persons as Self-consciously Concerned Beings Benjamin Abelson Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/824 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] PERSONS AS SELF-CONSCIOUSLY CONCERNED BEINGS by BENJAMIN ABELSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 i © 2015 BENJAMIN ABELSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Graham Priest May 18th, 2015 ____________________ Chair of Examining Committee John Greenwood May 18th, 2015 _____________________ Executive Officer John Greenwood Linda Alcoff Jesse Prinz Marya Schechtman Supervisory Committee iii Abstract PERSONS AS SELF-CONSCIOUSLY CONCERNED BEINGS by BENJAMIN ABELSON Advisor: Professor John D. Greenwood This dissertation is an analysis of the concept of a person. According to this analysis, persons are beings capable of being responsible for their actions, which requires possession of the capacities for self- consciousness, in the sense of critical awareness of one’s first-order desires and beliefs and concern, meaning emotional investment in the satisfaction of one’s desires and truth of one’s beliefs. -

7. the PROBLEMATIZATION of the TRIAD STYLE-GENRE- LANGUAGE in the DIDACTIC APPROACH of the DISCIPLINE the HISTORY of MUSIC Loredana Viorica Iațeșen18

DOI: 10.2478/RAE-2019-0007 Review of Artistic Education no. 17 2019 56-68 7. THE PROBLEMATIZATION OF THE TRIAD STYLE-GENRE- LANGUAGE IN THE DIDACTIC APPROACH OF THE DISCIPLINE THE HISTORY OF MUSIC Loredana Viorica Iațeșen18 Abstract: Conventional mentality, according to which, in the teaching activities carried out during the courses of History of Music, the approach of the triad style-genre-language is performed under restrictions and in most cases in a superficial manner, the professor dealing with the usual general correlations (information regarding the epoch, biography and activity of the creator, affiliation of the musician to a certain culture of origin, the classification of the opus under discussion chronologically in the context of the composer’s work) falls into a traditional perspective on the discipline brought to our attention, a perspective that determines, following the processes of periodical or final assessment, average results and a limited feedback from students. For these reasons, it is necessary to use the modern methods of approaching the discipline, new teaching strategies in the comments and correlations on scientific content, so that the problematization of the style-genre-language triad in didactic approach of the discipline The History of Music, to generate optimal results in specific teaching and assessment activities. Key words: romantic composer, orchestral lied, text-sound relationship, critical reception 1. Stage of research. Musicological perspective In our opinion, the teaching approach of the triad Style-Genre-Language during the courses of history of music involves a systematization of the most relevant titles in the musicological documentation, in order to establish some key-elements in the following study. -

Erica Amelia Reiter

Krzysztof Penderecki's Cadenza for Viola Solo as a derivative of the Concerto for Viola and Orchestra: A numerical analysis and a performer's guide Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Reiter, Erica Amelia, 1968- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 13:40:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289622 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproductioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the origmal, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book.