Beach Books: 2018-2019. What Do Colleges and Universities Want

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

The Inventory of the Everett Raymond Kinstler Collection #1705

The Inventory of the Everett Raymond Kinstler Collection #1705 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Kinstler, Everett Raymond #1705 8/9/05 Preliminary Listing I. Printed Material. Box 1 A. Chronological files; includes news clippings, periodicals, bulletins, and other items re: ERK and his artwork. 1. "1960-62." [F. 1] 2. "1963-64," includes photos. [F. 2] 3. "1965-66." [F. 3] 4. "1967-68." [F. 4] 5. "1969." [F. 5] 6. "1970." [F. 6] 7. "1971," includes photos. [F. 7] 8. "1972," includes photos. [F. 8] 9. "1973." [F. 9] 10. "1974." [F. 10] 11. "1975." [F. 11] 12. "1976." [F. 12] 13. "1977." [F. 13] 14. "1978." [F. 14] 15. "1979." [F. 15] Box2 16. "1980." [F. 1-2] 17. "1981." [F. 3-4] 18. "1982." [F. 5-6] 19. "1983." [F. 7] 20. "1984." [F. 8] 21. "1985." [F. 9] 22. "1986." [F. 10] 23. "1987." [F. 11] 24. "1988." [F. 12] 25. "1988-89." [F. 13] 26. "1990." [F. 14] 27. "1991." [F. 15] Box3 28. "1992." [F. 1] 29. "1993." [F. 2] 30. "1994." [F. 3] 31. "1995." [F. 4] 32. "1996." [F. 5] 33. "1997." · [F. 6] 34. "1998." [F. 7] 35. "1999." [F. 8] 36. "2000." [F. 9] Kinstler, Raymond Everett (8/9/05) Page 1 of 38 37. "2001." [F. 10-11] 38. "2002." [F. 12-13] 39. "2003." [F. 14] 40. "2004." [F. 15-16] II Correspondence. Box4 A. Letters to ERK arranged alphabetically; includes some responses from ERK. 1. Adams, James F. TLS, 5/16/62. [F. 1] 2. Adams,(?). ALS, Aug. -

1955 Guantanamo Bay Carnival Opens Today

" - -- _'-Vo- -- - 'oers CTMO Lke The Sunskine" Vol. VII, No. 7 U. S. Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Saturday, 19 February 1955 1955 Guantanamo Bay Carnival Opens Today Festivities Set to Run Four Days The 1955 edition of the Guantanamo Bay Carnival, featuring a 1955 Dodge Royal Sedan and a 1955 Ford Convertible as the top attractions, will get underway today for a gala four days. Opening its gates to the public this afternoon at 1300, the carnival will run for four big days; today until 2200, Sunday from 1300 to 2200, Monday from 1700 to 2200, and a grand finale day from 1000 to 2000 on Tuesday at the end of which time some two persons will not walk away, but drive off in a new Dodge andi a new Foind. Staged each year for the Guan- Base POs Complete Exams, tanamo Bay Naval Base Commnun- Rates Due in Group iy Fund, the carnival will offer On Tuesday, 22 Feb, second class entertainment of all sorts for all officers of the Naval Base ages with 19 entertainment booths, petty kiddie will compete in the service-wide eight refreshment booths, for advancement in rides, horseback riding, roller skat- examinations and a special to Pay Grade E-6, complet- ing, fortune telling, rating aexamnatons souvenir booth. This year, the car- ingring the to semi-annualPeiaay examinations. nvli eddb omte Then the waiting begins until late Ciran CP W. b. Carute April or early May when the re- suits of the four examinations, Commanding Officer, Naval Station. Pay Grades E-4, E-5, E-6, and R u n n i n g the entertainment E-7 will be returned from the ex- booths will be the Base Commands, amining center. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

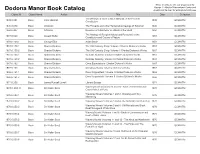

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

WINTER 2005 Recognized and Visible Component of for More Information Contact the Public and Private Planning

FAQ’s About the State and National Registers of Historic Places FRIENDS of the UPPER EAST SIDE HISTORIC DISTRICTS What are the State and National Registers Owners of historic commercial and similar – to protect and preserve of Historic Places? rental properties listed on the National properties important in our past. Administered by the State Historic Register may qualify for a preservation Will State and National Register listing Preservation Office (SHPO), which is tax credit. restrict the use of a property? part of the New York State Office of Not-for-profit organizations and Listing on the registers does not interfere Parks, Recreation and Historic municipalities that own listed with a property owner’s right to remodel, Preservation (OPRHP), the registers are properties are eligible to apply for New alter, paint, manage, sell, or even the official lists of properties that are York State historic preservation grants. demolish a historic property, local zoning significant in history, architecture, Properties that meet the criteria for and ordinances not withstanding. If state engineering, landscape design, registers listing receive a measure of or federal funds are used or if a state or archaeology and culture within local, state protection from state and federal federal permit is required, proposed and/or national contexts. More than undertakings regardless of their listing alterations will be reviewed by the SHPO’s 80,000 historic properties in New York status. staff – regardless of listing status. have received this prestigious recognition. How do State and National Registers differ Where can I find more about the State What are the benefits of being listed on the registers? from designation under the New York City and National Registers? The State and National Registers are a Landmarks Commission? WINTER 2005 recognized and visible component of For more information contact the public and private planning. -

Norms and Narratives: Can Judges Avoid Serious Moral Error Colloquy

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 1990 Norms and Narratives: Can Judges Avoid Serious Moral Error Colloquy Richard Delgado University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Jean Stefancic University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Richard Delgado & Jean Stefancic, Norms and Narratives: Can Judges Avoid Serious Moral Error Colloquy, 69 Tex. L. Rev. 1929 (1990). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/557 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. Norms and Narratives: Can Judges Avoid Serious Moral Error? Richard Delgado* and Jean Stefancic** I. Introduction .............................................. 1929 II. Notorious Cases and Saving Narratives: What the Juxtaposition Shows ...................................... 1934 A. Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson .................... 1934 B. Indian Cases ......................................... 1939 C. The Chinese Exclusion Case ........................... 1943 D. The Japanese Internment Cases ....................... 1945 E. Bradwell v. Illinois ................................... 1947 F Buck v. Bell .......................................... 1948 G. Bowers v. Hardwick .................................. 1950 III. Law and Literature: The Canon -

James Gould Cozzens: a Documentary Volume

Dictionary of Literary Biography • Volume Two Hundred Ninety-Four James Gould Cozzens: A Documentary Volume Edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book GALE" THOMSON GALE Detroit • New York • San Diego • San Francisco • Cleveland • New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich Contents Plan of the Series xxvii Introduction xxix Acknowledgments xxxiii Permissions xxxiv Books by James Gould Cozzens 3 Chronology 5 I. Youth and Confusion 9 Early Years 9 Brought Up in a Garden—from James Gould Cozzens's foreword to Roses of Yesterday (1967) Facsimile: Illustrated composition Facsimile: Staten Island Academy composition Two Poems-'The Andes," The Qwjfljanuary 1915, and "Lord Kitchener," Digby Weekly Courier, 16June1916 Kent School \ 15 A Democratic School-article by Cozzens, The Atlantic Monthly, March 1920 Emerson: "A Friendly Thinker"—essay by Cozzens, Kent Quarterly, December 1920 Books That Mattered—list of books Cozzens submitted to Christian Century, 22 August 1962 Harvard 19 The Trust in Princes-poem by Cozzens, Harvard Advocate, 1 November 1922 Remember the Rose—story by Cozzens, Harvard Advocate, 1 June 1923 A First Novel 22 Facsimile: Epigraph for Confusion Some Putative Facts of Hard Record or He Commences Authour Aetatis Suae 19-20-Cozzens letter to Matthew J. Bruccoli The Birth of Cerise: from Confusion Facsimile: Pages from Cozzens's 1923 diary: 24 February, 13 March, and 17 October The Death of Cerise: from Confusion Reception of Confusion 31 Harvard Undergrad, at 19, Has 'Best Seller' Accepted-Boston Traveller, 1 April 1924 ; Beebe Celebrates Cozzens-from The Lucius Beebe Reader and Beebe's review of Cozzens's novel in the Boston Telegram, 8 April 1924 A Voice From Young Harvard-C. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/113624 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. VINCENT PIKET Louis Auchincloss he Growth of a Novelist European University Press LOUIS AUCHINCLOSS THE GROWTH OF A NOVELIST LOUIS AUCHINCLOSS THE GROWTH OF A NOVELIST Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de letteren PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholieke Universiteit te Nijmegen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 5 april, 1989 des namiddags te 1.30 uur precies door VINCENT PIKET geboren op 12 juli 1959 te Nijmegen EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY PRESS NIJMEGEN 1989 Promotor: Prof. dr. G.A.M. Janssens Privately printed and distributed by: European University Press P.O. Box 1052 6501 BB Nijmegen The Netherlands Photograph by courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Company Copyright Vincent Plket, 1989 CIP Data Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague Plket, Vincent Louis Auchincloss : The Growth of a novelist / Vincent Plket. - Nijmegen : European University Press Ook verschenen in handelseditie: Nijmegen : European University Press, 1989. - Proefschrift Nijmegen. Incl. bibliogr. ISBN 90-72897-02-1 SISO enge-a 856.6 UDC 929 Auchincloss, Louis Stanton+820(73)n19,,(043.3) NUGI 953 Trefw.: Auchincloss, Louis Stanton. CONTENTS Acknowledgments lil Introduction 1 -

A Study of Some Male Characters in Edith Wharton's Novels a Study of Some Male Characters in Edith Wharton's Novels

A STUDY OF SOME MALE CHARACTERS IN EDITH WHARTON'S NOVELS A STUDY OF SOME MALE CHARACTERS IN EDITH WHARTON'S NOVELS By JUDITH TAYLOR, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University August, 1981 To my parents. MASTER OF ARTS (1981) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: A Study of Some Male Characters in Edith Wharton's Novels AUTHOR: Judith Taylor, B.A. (London University, England) SUPERVISOR: Dr. F. N. Shrive NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 93 ii ABSTRACT Edith Wharton has been criticised for her portrayal of male characters. They are often dismissed as being mainly one type: the inadequate, aristocratic, dilettante gentleman. This thesis argues that whilst this figure re-occurs in her work a development can be seen from Lawrence Selden of The House of Mirth, to Ralph Marvell of The Custom of the Country culminating in Newland Archer, hero of The Age of Innocence. Furthermore these men are not carbon copies of each other, but independent characters in their own right. Finally, it will be shown that there is a considerable range of male characters to be found playing secondary roles in her work. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to my Supervisor, Dr. F. N. Shrive for his patience and assistance. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION. • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • • • • .• 1 I HEROES AND THEORIES • . • • • • • • • • •. 9 II THE HOUSE OF MIRTH. • • • • • • • . • • • • • • 30 III THE CUSTOM OF THE COUNTRY • • • • • • • • • •• 49 IV THE AGE OF INNOCENCE. • • . • . • . • •• 66 CONCLUSION. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 85 BIBLIOGRAPHY. -

The Inventory of the Louis Begley Collection #1473

The Inventory of the Louis Begley Collection #1473 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Begley, Lquis 02/26/99 Preliminalp' Listing Box 1 I. Manuscripts A By LB 1. MISTLER'S EXIT (total: 13 drafts) l. l st dratt--underthe---altemate-title: "Mistler' s End." Computer script with holograph corrections and text inserts. 2. Jufy-P\ 1996-dr_:aft_nnd_er_altematetitle-7 '~"s-Out." Computer script witlr exterrsiv_e holo_gr,wh corrJ)ctions, 231 pg. 3 _ July <½111, ·19%-draft-. £omputer script-with holo_graph correcti-ons; 231 pg. th A_ .July M , -19% draft_ -Com:pnter_scri_pt with:.holc,graph .eorr-ections, 232 pg. 5. 2 drafts (one incomplete). Computer script with holograph _corr_ections, 229 pg. 6. M"l,Y 8, 1997 draft. Computer script, 228 pg. 'J. Au_gust 5-.,J 927. Colllputer script with Jielograph corre_ctions, 229 pg. /8. Nov._23_, J~J draft. Computer script with holograph correction~ and author's notes on text, 229 pg. _9. Nov.-24, 1997 dr_aft. Com_putecscript with.George Anderson'f corrections, 235 pg. LO. Setting cgpy. Cofi!Putecscript with setter's corrections, .- 2J5 pg. 11. Page-proofmastei pt_pas-sonMarch 18-, t998. Com_pttter script with holograph corrections, 205 pg. 12.. Page:_pmnf_rnster l1"1-pass-on April 21, 1998. Computer script with holggn1,ph corr~.et-ions, 206 pg. Box2 2. WAR1]ME-LIE_S (total: 12 drafts) _ -8:. 1 sttkaft. -Crun-ptttef :Seript., :2'01 pg. b. _2m1 draft:Computer~with holograph correctionsand author's notes; 194 pg. c. 4 drafts. Computer script with holograph corrections and author's notes, 220- 240 pg. d. Set1ing copy.