Why Cultural Heritage Matters a Resource Guide for Integrating Cultural Heritage Management Into Communities Work at Rio Tinto About Rio Tinto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASX Market Announcements Australian Securities Exchange SYDNEY NSW 2000 13 September 2012 Dear Sir, Attached Is a Presentati

120 Collins Street Melbourne 3000 Australia Postal Address: GPO Box 384D Melbourne 3001 Australia T +61 (0) 3 9283 3333 F +61 (0) 3 9283 3707 ASX Market Announcements Australian Securities Exchange SYDNEY NSW 2000 13 September 2012 Dear Sir, Attached is a presentation given by Alan Davies, Chief executive, Rio Tinto Diamonds & Minerals, Bruce Cox, Managing director, Rio Tinto Diamonds, Jean-Francois Turgeon, Managing director, Rio Tinto Iron & Titanium and Xiaoling Liu, President and Chief executive, Rio Tinto Minerals, as part of a financial community visit in Montreal, Canada. Yours faithfully, Stephen Consedine Company Secretary Registered in Australia Rio Tinto Limited 120 Collins Street Melbourne 3000 Australia ABN 96 004 458 404 Rio Tinto Diamonds & Minerals Fuelling consumer-driven economic growth Alan Davies Chief executive 12 September 2012 Cautionary statement This presentation has been prepared by Rio Tinto plc and Rio Tinto Limited (“Rio Tinto”) and consisting of the slides for a presentation concerning Rio Tinto. By reviewing/attending this presentation you agree to be bound by the following conditions. Forward-looking statements This presentation includes forward-looking statements. All statements other than statements of historical facts included in this presentation, including, without limitation, those regarding Rio Tinto’s financial position, business strategy, plans and objectives of management for future operations (including development plans and objectives relating to Rio Tinto’s products, production forecasts and reserve and resource positions), are forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance or achievements of Rio Tinto, or industry results, to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward- looking statements. -

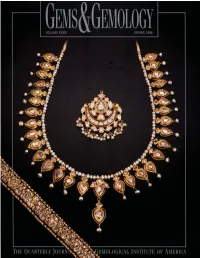

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Discover Lbb

STRATEGISTS IN SPORT AND ACTIVE LIVING DISCOVER LBB www.lbbsport.com WHO WE ARE OUR TEAM IS FUELED BY 2 SPORT AND ACTIVE LIVING Béatrice Girardin Project Analyst Passionate about Sport and Active Living since 2000 Benoit Girardin is LBB SPORT’s owner and leader working with a team of 30 staff and multidisciplinary experts in sport and Caroline Assalian - Collaborating Expert Benoit Girardin - LBB’s owner active lifestyle. Julie Dussault Jonathan Demers - Project Manager Accountant Benoit is a sports lawyer and business entrepreneur that has been involved Our purpose is to in amateur, olympic and professional sports for the last 30 years. He is a trained support, advise, facilitator, mediator and professor in sport business and law at HEC (University of inspire and Montréal), McGill and Ottawa universities Manon Huttin empower those who Branding & Marketing and visiting professor in Europe, USA as well as speaker at national and believe in the power international sports conferences. of sport and active LBB’s experts and collaborators living have expertise in strategic planning, organizational performance, governance, revenue generation, government relations, marketing and communication, sports law, major sporting events, sport and active living facilities, programming and high-performance. At LBB, we foster collaboration between our next generation of leaders and experienced experts to offer superior value and the best project teams to meet our clients’ needs. Our team is your team! LBB SPORT and LBB STRATEGIES are trademarks and divisions -

Global Rough Diamond Production Since 1870

GLOBAL ROUGH DIAMOND PRODUCTION SINCE 1870 A. J. A. (Bram) Janse Data for global annual rough diamond production (both carat weight and value) from 1870 to 2005 were compiled and analyzed. Production statistics over this period are given for 27 dia- mond-producing countries, 24 major diamond mines, and eight advanced projects. Historically, global production has seen numerous rises—as new mines were opened—and falls—as wars, political upheavals, and financial crises interfered with mining or drove down demand. Production from Africa (first South Africa, later joined by South-West Africa [Namibia], then West Africa and the Congo) was dominant until the middle of the 20th century. Not until the 1960s did production from non-African sources (first the Soviet Union, then Australia, and now Canada) become impor- tant. Distinctions between carat weight and value affect relative importance to a significant degree. The total global production from antiquity to 2005 is estimated to be 4.5 billion carats valued at US$300 billion, with an average value per carat of $67. For the 1870–2005 period, South Africa ranks first in value and fourth in carat weight, mainly due to its long history of production. Botswana ranks second in value and fifth in carat weight, although its history dates only from 1970. Global production for 2001–2005 is approximately 840 million carats with a total value of $55 billion, for an average value per carat of $65. For this period, USSR/Russia ranks first in weight and second in value, but Botswana is first in value and third in weight, just behind Australia. -

Guide Média 2 Table of Content Tables Des Matières

MEDIA GUIDE | GUIDE MÉDIA 2 Table of Content Tables des matières About Swimming Canada ............................................................................................................p.4 À propos de Natation Canada About the Canadian Olympic & Paralympic Swimming Trials presented by RBC.......................p.6 Au sujet des essais olympiques et paralympiques canadiens de natation présentés par RBC The Fast Facts about Para-swimming at the 2012 Paralympic Trials.........................................p.10 En bref au sujet de la paranatation aux essais paralympiques 2012 Biographies Men/Hommes Women/Femmes Isaac Bouckley p.12 Camille Berube p.34 Devin Gotell p.14 Morgan Bird p.36 Michael Heath p.16 Valerie Grand-Maison p.38 Brian Hill p.18 Brianna Jennett-McNeill p.40 Benoit Huot p.20 Kirstie Kasko p.42 Danial Murphy p.22 Sarah Mailhot p.44 Scott Patterson p.24 Sarah Mehain p.46 Michael Qing p.26 Summer Mortimer p.48 Brianna Nelson p.50 Adam Rahier p.28 Maxime Olivier p.52 Nathan Stein p.30 Aurelie Rivard p.54 Donovan Tildesley p.32 Katarina Roxon p.56 Rhea Schmidt p.58 Amber Thomas p.60 National Records Records nationaux p.62 Event Schedule Horaire de la compétition p.70 Media Contact: Martin RICHARD, Director of Communications, mrichard@swimming,ca, mob. 613 725.4339 3 About Swimming Canada Swimming Canada serves as the national governing body of competitive swimming. Competitive Canadian swimming has a strong heritage of international success includ- ing World and Olympic champions Cheryl Gibson, Victor Davis, Anne Ottenbrite, Alex Baumann, and Mark Tewksbury, among many others. Swimming Canada is proud to be a leading sport federation for the integration of athletes with a disability with its National Team and competitive programs. -

Ecological Comparison of Synthetic Versus Mined Diamonds

Ecological Comparison of Synthetic versus Mined Diamonds Saleem H. Ali Working Paper, Institute for Environmental Diplomacy and Security University of Vermont, January, 2011 http://www.uvm.edu/ieds Abstract The energy usage and emissions in mined versus lab-created diamonds was evaluated, based on industrial data, since these two factors are often a general indicator of environmental impact that can be useful in product comparisons. Depending on the process and the location of the mine, the data can be highly divergent and cannot be used as a singular measure of environmental impact. There is a need to develop life cycle analysis techniques from industrial ecology to conduct a detailed comparison of synthetic versus mined stones. Introduction Synthetic diamonds have come of age, and the year 2010 will be remembered as a landmark year in this regard since for the first time labs of the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in New York were able to grade a gem quality near-colorless synthetic diamond (formed by chemical vapor deposition) , greater than 1 carat. The history of synthetic diamonds at the industrial level, goes back to patents for super-abrasives at General Electric can be traced back to several decades (Hazen, 1996). However, gem quality synthetic diamonds have only risen to prominence in the last decade with the rise of a few key companies who are taking on this growing market in concert with boutique jewelry brands. As jewelers consider environmental social responsibility more seriously in marketing their gemstone products, energy usage in mined versus lab-created gems can be an important factor in determining comparative environmental impact. -

Patrice Brunet, LL.B., C. Dir., ASC

Patrice Brunet, LL.B., C. Dir., ASC 630 Sherbrooke W. Suite 307 Montreal (Quebec) H3A 1E4 +1-514-887-7111 (Montreal) +971-50-240-1348 (Dubai) [email protected] Fluent in English and French (written and spoken) Professional Experience Owner, NEXT Group FZ LLE January 2013 to Present NEXT Group is a Dubai-based legal consultancy, offering arbitration and project management services for individuals and corporations. Manager, Business Development and Legal Affairs Sept. 2011 to January 2013 NRS International Dubai, UAE NRS International is an industry leader in manufacturing, developing and supplying core relief items for the humanitarian aid sector. Owner May 1993 – August 2011 Brunet Lawyers Montreal, Canada Brunet Lawyers was a leading law firm, specialized in providing business immigration and sports arbitration services. Patrice Brunet 1 [email protected] EDUCATION Chartered Director (C. Dir.) 2010 The Directors College, program recognized by McMaster University Hamilton, Canada Administrateur de Sociétés Certifié (ASC) 2010 Program recognized by Laval University Quebec, Canada Quebec Law Society 1992 Ecole du Barreau du Québec Montreal, Canada Bachelor of Law (LL.B.) 1991 University of Montreal Montreal, Canada Faculty of Arts and Science 1987-1988 York University Toronto, Canada ** Various and numerous training programs and seminars periodically provided by the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada, the Court of Arbitration for Sport and the United States Anti-Doping Agency ** BOARD AND MEMBER -

The World of Pink Diamonds and Identifying Them

GEMOLOGY GEMOLOGY as to what dealers can do to spot them using standard, geologists from Ashton Joint Venture found certain indicator The World of Pink Diamonds inexpensive instruments. The commercial signifcance of minerals (such as ilmenite, chromite, chrome diopside, the various types will also be touched on. and pyrope garnet) in stream-gravel concentrates which indicated the presence of diamond-bearing host rocks. and Identifying Them Impact of Auction Sales Lamproites are special ultrapotassic magnesium-rich In the late 1980s, the public perception surrounding fancy- mantle-derived volcanic rocks with low CaO, Al2O3, Na2O colored diamonds began to change when the 0.95-carat and high K2O. Leucite, glass, K-richterite, K-feldspar and Cr- By Branko Deljanin, Dr Adolf Peretti, ‘Hancock Red’ from Brazil was sold for almost $1 million per spinel are unique to lamproites and are not associated with and Matthias Alessandri carat at a Christie’s auction. This stone was studied by one kimberlites. The diamonds in lamproites are considered to be of the authors (Dr. Adolf Peretti) at that time. Since then, xenocrysts and derived from parts of the lithospheric mantle Dr. Peretti has documented the extreme impact this one that lies above the regions of lamproite genesis. Kimberlites sale has had on subsequent prices and the corresponding are also magmatic rocks but have a different composition recognition of fancy diamonds as a desirable asset class. The and could contain non-Argyle origin pink diamonds. demand for rare colors increased and the media began to play a more active role in showcasing new and previously Impact of Mining Activities unknown such stones. -

Investing in Colored Diamonds from Diamond Investment Dealers

BENEFITS OF INVESTING IN COLORED DIAMONDS FROM DIAMOND INVESTMENT DEALERS When investing in diamonds you need an ad- ly appreciated in value. Over the last decade, visor who has the depth and breadth of knowl- Argyle pink diamonds have consistently bro- edge in investment grade diamonds. Rare ken records on the global auction market, Diamond Investor provides seamless access demonstrating the robust nature of the dia- for savvy investors. We focus exclusively on mond market and the unceasing international natural fancy-colored diamonds and are staffed demand. Christies auctions have surpassed by experts in every facet of the diamond mar- records the last few years for both the most ket. This level of experience and expertise not expensive investment grade diamonds and only gives us greater understanding of the di- the highest price per carat. In April 2014, Chris- amond market, but also gives us access to a ties auctioned top quality, fancy pink, blue professional global network of investors, col- and yellow diamonds with prices exceeding of lectors and industry specialists including the $1 to $2 million per carat, leading Christies most sought after gemologists and diamond to declare 2014 the year of the colored dia- cutters in the world. mond. Rahul Kadakia, Head of Christies New York, states, At a time when other investments have suf- fered unparalleled chaos and uncertainty, “A colorless D-grade diamond at auction will make about $150,000 a carat, while a pink natural fancy-colored diamonds have steadi- fancy-colored diamond will make $1.5 million a carat, 10 times the price.” He also stated, “This is where the market is. -

Australian Diamond Deposits, Kimberlites, and Related Rocks Known Diamondiferous Fields and Locations on the 1:5 000 000 Scale Map, Geoscience Australia, Canberra

50 120` 51 126`52 132` 53 138` 54 144` 55 150` 8` 8` TO TIMOR SEA RRES STRAIT NORTH KIMBERLEY FIELD 114` MERLIN FIELD MERLIN FIELD Fohn 1 TORRES STRAIT SC Emu 1, 2 Gareth, Kay Bedevere Ector Ywain, Tristram, Gawain ARNHEM Palomides, Sacramore, Maningrida Launfal, Excalibur SC Milingimbi Nhulunbuy DARWIN Weipa PINE CREEK 12` 12` AustralianAustralian DiamondDiamond Deposits,Deposits, Joseph Daly RIver Pine Creek Stow 1 Mining operations at Ellendale, West Kimberley, W.A. Bonaparte (Photo courtesy of Kimberley Diamond Company NL). Kimberlites,Kimberlites, andand RelatedRelated RocksRocks Gulf LITCHFIELD McARTHUR Numbulwar COR Katherine AL Gulf Ashmore Piipes SEA Scale 1:5000000 Ngukurr Seppellt Piipes Roper Kimberley of 0 90 180 270 360 450 Kilometers North K COEN LAMBERT CONFORMAL CONIC PROJECTION Carpenteria SD Central Meridian : 134`E Stand Parallels : 18`S, 36`S Timber Creek Kowanyama SD Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 Wyndham KIMBERLEY Kununurra Cooktown VICTORIA RIVER Argyle Mine Abner Range Emu Bow River Alluvials Maude Creek Kim 6, 14, 13 Ellendale 17 Napier 2, 3 ke Creek Merlin Mossman Carpenter Gap Ariies Smoke El 26 17, 12, 16 Kim 3 El 427BW, 27BE Palomides Gareth El 25 El 18, 18b Napier 1 ips Range HALLS Sacramore Launfal North CAIRNS Mt North Phillip Launfal El 41, 42, 43 El 19 Ellendale 46 CREEK Cairns Prima 3 KING LEOPOLD Elliott Prima 2 berley Karumba 16` El 44, 24 5 El 40 Kimberley 21, 23, El 36 East Kimb MURPHY 16` 27 El 21, 21A Atherton El 37 Kim 10 El 16 Derby pring Coanjula Burketown Normanton 4 El 9 Ellendale 39 Big Sp 9 Kim 25 El 8 Ellendale 9 Kim 7, 8 El 22 11 El 13 Kimberley 29, 19 Kimberley 28, 34, El 11 Diamonds from Ellendale 9, West Kimberley, W.A. -

GEOLOGY and DEVELOPMENT of the LOMONOSOV DIAMOND DEPOSIT, NORTHWESTERN RUSSIA Karen V

FEATURE AR ICLES GEOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE LOMONOSOV DIAMOND DEPOSIT, NORTHWESTERN RUSSIA Karen V. Smit and Russell Shor The Siberian craton in Russia hosts many of the country’s famous diamond mines.The Lomonosov mine, however, occurs within the boundaries of a different craton—the Baltic shield, most of which lies in Eu- rope. Unlike many diamond mines in South Africa, Canada, and Siberia, the Lomonosov deposit is not in a stable Archean geologic setting. Similar to the Argyle diamond mine in Australia, Lomonosov is in a younger Proterozoic orogenic (or mountain-building) region. Fancy pink diamonds at both these lo- calities likely relate to these Proterozoic tectonic processes. Along with other diamond mines in Pro- terozoic geologic regions, the Lomonosov deposit (and its fancy-color diamond inventory) demonstrates that the diamond potential of these regions should not be overlooked. ussia has been a major diamond producer for In August 2016, the authors visited the Lomonosov more than half a century. Most of its diamond deposit to document this exciting new diamond local- Rmines occur in the semi-autonomous Sakha ity. The visit included tours of the kimberlite open-pit Republic within the geological bounds of the Siberian operations, the processing plant, and the preliminary craton. However, over the last 12 years, Alrosa, a pub- diamond sorting facilities in the city of Arkhangelsk. lic joint-stock company (with both government and The authors also visited Alrosa’s central diamond sort- private ownership) operating through its subsidiary ing and sales operation, the United Selling Organisa- Severalmaz, has started development and mining at tion (USO) in Moscow. -

Table of Content Table Des Matières

1 www.natation.ca TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE DES MATIÈRES THE SPORT OF SWIMMING / LE SPORT DE LA NATATION Origins of the Paralympic Games/ p.5 Origines des Jeux Paralympiques The Sport / Le Sport p.7 SWIMMING CANADA / NATATION CANADA About Swimming Canada / p.13 À propos de Natation Canada The Sport of Swimming Vision / Mission Laymans Guide to Classification / Guide d’interprétation des classifications à l’intention du profane p.17 Le sport de la natation BIOGRAPHY / BIOGRAPHIE Women’s Bios / Biographie des femmes p.23 Men’s Bios / Biographie des hommes p.57 Coaches / Entraîneurs p.71 Staff / Personnel Media Contact / Contact pour les médias p.77 STATISTICS / STATISTIQUES Canadian Records / Records canadiens World Records / Records du monde p.81 Medals won at the Paralympic Games / p.130 Médailles remportées aux Jeux Paralympiques SCHEDULE / HORAIRE Competition Schedule & Who to watch / Horaire des épreuves p.133 www.swimming.ca 2 3 Paralympics Profile History of the Paralympics The Paralympic movement began back in 1948 when Sir Ludwig Guttman organized a sports competition involving World War II veterans with a spinal cord injury in Stoke, Mandeville, England. In 1952, the Netherlands joined the competition and an international movement was born. The very first Olympic style Games for athletes with a disability were organized in Rome in 1960. In Toronto in 1976, other disability groups, other than spinal cord injuries, were added and the idea of merging various disability groups for international sport competitions began. In the same year, the first Paralympic Winter Games took place in Sweden. Today, the Paralympics are elite sport events for athletes from six different disability groups.