Is It Still About 'The Split'? the Ideological Basis of 'Dissident' Irish Republicanism Since 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

Partnership Panel Committee Report Submitted To: Council Meeting

Title of Report: Partnership Panel Committee Council Meeting Report Submitted To: Date of Meeting: 6 October 2020 For Decision or For Decision For Information Linkage to Council Strategy (2019-23) Strategic Theme Leader and Champion Outcome We will establish key relationships with Government, agencies and potential strategic partners in Northern Ireland and external to it which helps us to deliver our vision for this Council area. Lead Officer Director of Corporate Services Budgetary Considerations Cost of Proposal N/A Included in Current Year Estimates N/A Capital/Revenue N/A Code N/A Staffing Costs N/A Screening Required for new or revised Policies, Plans, Strategies or Service Delivery Requirements Proposals. Section 75 Screening Completed: Yes/No Date: Screening EQIA Required and Yes/No Date: Completed: Rural Needs Screening Completed Yes/No Date: Assessment (RNA) RNA Required and Yes/No Date: Completed: Data Protection Screening Completed: Yes/ No Date: Impact Assessment DPIA Required and Yes/No Date: (DPIA) Completed: 201006 – Partnership Panel Key Outcomes Note – Version No. 1 Page 1 of 2 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 The Purpose of the Report is to present the Key Outcomes Note from the Partnership Panel. 2.0 Background 2.1 The Northern Ireland Partnership Panel convened for the first time in four years on 16 September 2020. This Outcomes Note is provided by NILGA, the Northern Ireland Local Government Association, to provide an immediate update to all 11 member councils. Full Minutes will follow. 3.0 Recommendation(s) 3.1 It is recommended that Council note the Partnership Panel Key Outcomes Note, dated 16 September 2020. -

Committee for the Executive Office

Committee for The Executive Office OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) United Kingdom Exit from the European Union: Mr Declan Kearney and Mr Gordon Lyons, Junior Ministers, The Executive Office 26 May 2021 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY Committee for The Executive Office United Kingdom Exit from the European Union: Mr Declan Kearney and Mr Gordon Lyons, Junior Ministers, The Executive Office 26 May 2021 Members present for all or part of the proceedings: Mr Colin McGrath (Chairperson) Ms Martina Anderson Mr Trevor Clarke Mr Trevor Lunn Mr Pat Sheehan Ms Emma Sheerin Mr Christopher Stalford Witnesses: Mr Kearney junior Minister Mr Lyons junior Minister The Chairperson (Mr McGrath): Ministers, you are very welcome. Thank you for coming along today to give us an update. I can pass over to you to give us an oral briefing, after which we will move to questions. Thank you very much indeed. Mr Kearney (Junior Minister, The Executive Office): Go raibh maith agat. Is é bhur mbeatha, a chomhaltaí uilig ar líne an tráthnóna seo. It is good to see you all again. Thank you. To kick off, Gordon and I will provide a short update on EU exit issues since we last met. At our last appearance before the Committee, we advised that the co-chair of the Joint Committee, David Frost, and his EU counterpart, Maroš Šefčovič, were continuing to discuss issues associated with the protocol and that they had agreed to further engagement with our local business groups, civil society and other stakeholders. The Committee will be aware that, in week commencing 10 May — the week before last — David Frost spent two days here, during which he met in person a range of businesses from across various sectors, as well as community representatives. -

Document Pack Committee and Members’ Services Section Rd 3 Floor, Adelaide Exchange 24-26 Adelaide Street Belfast BT2 8GD

Document Pack Committee and Members’ Services Section rd 3 Floor, Adelaide Exchange 24-26 Adelaide Street Belfast BT2 8GD 26 th February, 2009 MEETING OF HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES COMMITTEE Dear Councillor, The above-named Committee will meet in the Council Chamber, 3rd Floor, Adelaide Exchange on Wednesday, 4th March, 2009 at 4.30 pm, for the transaction of the business noted below. You are requested to attend. Yours faithfully PETER McNANEY Chief Executive AGENDA: 1. Routine Matters (a) Apologies (b) Minutes Minutes of the meeting of 4 th February 2. Directorate (a) Media Coverage (Pages 1 - 4) 3. Building Control (a) Energy Performance Certificate Enforcement (Pages 5 - 8) (b) Building Control Convention 2009 (Pages 9 - 10) (c) Applications for the Erection of Dual-Language Street Signs (Pages 11 - 12) (d) Naming of Street (Pages 13 - 14) - 2 - 4. Environmental Health (a) Appointment to Local Government Emergency Management Group's Radiation Monitoring Co-ordinating Committee (Pages 15 - 18) (b) Employment of Hate Crime Officer (Pages 19 - 116) (c) Tackling Health Inequalities Conference (Pages 117 - 122) (d) Response Plan for Suicide Clusters (Pages 123 - 132) 5. Waste Management (a) Tender for the Collection and Recycling of Mixed Timber from Recycling Centres (Pages 133 - 134) (b) Acceptance of Clays and Soils at the Former Dargan Road Landfill Site (Pages 135 - 138) (c) Chartered Institution of Wastes Management Conference (Pages 139 - 144) Page 1 Agenda Item 2a Belfast City Council Report to: Health and Environmental Services Committee Subject: Media Coverage Date: 4th March, 2009 Reporting Officer: Mr William Francey, Director of Health & Environmental Services, ext 3260 Contact Officer: Ms Joanne Lowry, Media Relations Officer, ext 6270 Relevant Background Information Members agreed that a quarterly report on media coverage would be brought to committee to keep members up to date on current issues. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland News Catalog - Irish News Article

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Bereaved urge Adams — reveal truth on HOME agents This article appears thanks to the Irish News. History (Allison Morris, Irish News) Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The children of a Co Tyrone couple murdered by loyalists have challenged Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams to call on the IRA to reveal publicly what it knows about British agents Book Reviews working in its ranks. & Book Forum Charlie Fox (63) and his wife Tess (53) were shot at their Search / Archive home in Moy, Co Tyrone, in September 1992 by the UVF. Back to 10/96 Mrs Fox was hit in the back. Her husband was shot in the Papers head. Reference Their children spoke out yesterday (Tuesday) after a Sinn Féin 'march for truth' on Sunday which called for collusion between the British state and loyalists to be exposed and at About which Mr Adams said: "Yes, the British recruited, blackmailed, tricked, intimidated and bribed individual republicans into working for them and I think it would be Contact only right to have this dimension of British strategy investigated also." Leading loyalist Laurence George Maguire was convicted in 1994 of directing the UVF gang responsible for murdering Mr and Mrs Fox. A week before the couple's deaths their son Patrick Fox was jailed for 12 years for possession of explosives. He said yesterday that while he welcomed Mr Adams's call for disclosure on British collusion with loyalists, the truth about republican agents must be revealed. "We know now that there were moves towards a ceasefire being made as far back as 1986," he said. -

Annual Report 2005

annual report for 2008 – 2009 produced by Young at Art Ltd 15 Church Street, BELFAST BT1 1PG Web: www.youngatart.co.uk Company Number NI 37755 Charity Ref: XR 36402 introduction 2008 – 2009 marked Young at Art’s 10th year in operation and 11th festival. The organisation delivered projects and activities to around 27,413 children and adults in Belfast, Northern Ireland and also in England, time and again achieving its vision to make life for children and young people as creative as possible through the arts. While the company continued to experience growth in its activities and its turnover, it also was a year of change as committed staff members moved on to new challenges. Following their departure, the organisation agreed to review its staffing structure and examine it in relation to a new company strategy from 2010. “All in all a fabulous festival, we loved it.... roll on next year!” contents Festival 2008 Page 2 Festival Goes To The Waterworks Page 3 Projects Page 4 Touring & Commissions Page 6 Advocacy & Development Page 7 Management Page 9 Funding & Finance Page 10 Appendices Page 12 I. Personnel II. Attendance & participation figures III. Marketing & print IV. Press & publicity Copies of this report and an executive summary are available from the Young at Art office or for download from the website. The text and images contained in this report remain the property of Young at Art and its featured artists. No duplication or use is permitted in part or in full in any territory without prior consent. 1 Festival 2008 The 2008 festival was inspired by the water that surrounds this island and the wind that sweeps through the city from the sea and the mountains. -

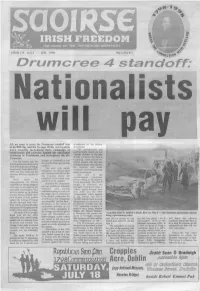

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

Derry's Drug Vigilantes

NEWS FEATURE DERRY’S DRUG VIGILANTES Ray Coyle was gunned down as he chatted to customers at his city centre shop in Derry. His crime? Selling legal highs. Max Daly reports on how dissident Republican groups are using the region’s historical distrust of drug dealers to drum up support in Northern Ireland’s still-fractured working class communities. IT WAS afternoon rush hour in the from within the local community”, had can buy legal highs over the internet, so centre of Derry, Northern Ireland’s claimed responsibility for the attack. are they going to start shooting postmen second city. Office workers hurried home The Red Star shooting, on January for delivering it?” through the bitter January cold. Inside 27 this year, marked an escalation in RAAD responded by saying Coyle and Red Star, a ‘head shop’ selling cannabis an already rising wave of attacks by other legal high sellers in the city had paraphernalia, hippy trinkets and dissident Republican paramilitary groups been warned, through leaflets handed exotically named legal highs, shopkeeper on drug dealers in Derry. out in pubs and personal visits to shops, Ray Coyle was chatting to customers But the attack on Coyle, which came to desist in “the hope moral thinking when a man wearing a motorcycle in the wake of a dramatic rise in reports would prevail”. Coyle denied he had been helmet barged through the door. of Derry teenagers being harmed by the warned by anyone. What is for certain is “Are you Raymond Coyle?” he now banned legal high mephedrone, was that RAAD published a statement in the demanded through his visor. -

Review of the Number of Members of the Northern Ireland Legislative

Assembly and Executive Review Committee Review of the Number of Members of the Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly and on the Reduction in the Number of Northern Ireland Departments Part 1 - Number of Members of the Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee relating to the Report, the Minutes of Evidence, Written Submissions, Northern Ireland Assembly Research and Information Papers and Other Papers Ordered by the Assembly and Executive Review Committee to be printed on 12 June 2012 Report: NIA 52/11-15 (Assembly and Executive Review Committee) REPORT EMBARGOED UNTIL COMMENCEMENT OF THE DEBATE IN PLENARY Mandate 2011/15 Second Report Committee Powers and Membership Committee Powers and Membership Powers The Assembly and Executive Review Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Section 29A and 29B of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and Standing Order 59 which provide for the Committee to: ■ consider the operation of Sections 16A to 16C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and, in particular, whether to recommend that the Secretary of State should make an order amending that Act and any other enactment so far as may be necessary to secure that they have effect, as from the date of the election of the 2011 Assembly, as if the executive selection amendments had not been made; ■ make a report to the Secretary of State, the Assembly and the Executive Committee, by no later than 1 May 2015, on the operation of Parts III and IV of the Northern Ireland Act 1998; and ■ consider such other matters relating to the functioning of the Assembly or the Executive as may be referred to it by the Assembly. -

Cooperation Programmes Under the European Territorial Cooperation Goal

Cooperation programmes under the European territorial cooperation goal CCI 2014TC16RFPC001 Title Ireland-United Kingdom (PEACE) Version 1.2 First year 2014 Last year 2020 Eligible from 01-Jan-2014 Eligible until 31-Dec-2023 EC decision number EC decision date MS amending decision number MS amending decision date MS amending decision entry into force date NUTS regions covered by IE011 - Border the cooperation UKN01 - Belfast programme UKN02 - Outer Belfast UKN03 - East of Northern Ireland UKN04 - North of Northern Ireland UKN05 - West and South of Northern Ireland EN EN 1. STRATEGY FOR THE COOPERATION PROGRAMME’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE UNION STRATEGY FOR SMART, SUSTAINABLE AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH AND THE ACHIEVEMENT OF ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND TERRITORIAL COHESION 1.1 Strategy for the cooperation programme’s contribution to the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and to the achievement of economic, social and territorial cohesion 1.1.1 Description of the cooperation programme’s strategy for contributing to the delivery of the Union strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and for achieving economic, social and territorial cohesion. Introduction The EU PEACE Programmes are distinctive initiatives of the European Union to support peace and reconciliation in the programme area. The first PEACE Programme was a direct result of the European Union's desire to make a positive response to the opportunities presented by developments in the Northern Ireland peace process during 1994, especially the announcements of the cessation of violence by the main republican and loyalist paramilitary organisations. The cessation came after 25 years of violent conflict during which over 3,500 were killed and 37,000 injured.