An Overview of Financial Management 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investors' Awareness of Fundamental and Technical Analysis For

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8 Issue-9, July 2019 Investors’ Awareness of fundamental and Technical Analysis for Investments in Securities Market Jayalakshmi. R, N. Lakshmi Abstract: The role of investors in the securities market reveals the rising prominence of financial savings and also the II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE growth of industry and the economy. The focal point is to survey the investors’ awareness of the fundamental and technical Wiwik Utami (2017) conducted a case study on investors’ analysis for investment in the securities market. The study stock investment decisions in Indonesia. The result showed identified an analysis of the economy, industries and companies that the period of investment and experience influenced the as the three fundamental components that influence and affect method of security analysis adopted before investment the investors’ investment in the securities market. decisions. Technical analysis was mostly preferred by Keywords: securities market, investors, rising prominence, regular tradinginvestors for quick decision-making. financial savings & technical analysis. Prasaanna Prakash (2016) found that the retail investors were less aware of the various investment options and the I. INTRODUCTION protective measures taken by the government. A majority of Investment in the securities market needs analysis to the retail investors chose investments for a short duration. identify and select the right instruments and right time to The researcher suggested that the retail investors be given invest to reap high returns, which in turn, can increase the proper attention. Investors’ decisions were based on investors’ wealth. Based on the analysis, the investment psychological, emotional and behavioral factors. -

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks Pump and dump stocks make me sick and just to be clear I do not trade these setups. When I look at a stock chart I normally see bulls and bears battling to see who will come out on top. However, when I look at a pump and dump stock it just saddens me. For those of you that watched the show Spartacus, it’s like when Gladiators have to fight outside of the arena and in dark alleys. As I see the sharp incline up and subsequent collapse, I think of all the poor souls that have lost IRA accounts, college savings and down payments for their homes. Well in this article, I’m going to cover 2 ways you can profit from these setups and clues a pump and dump scenario is taking place. Before we hit the two strategies, let’s first ground ourselves on the background of pump and dump stocks. What is a Pump and Dump Stock? These are stocks that shoot up like a rocket in a short period of time, only to crash down just as quickly shortly thereafter. The stocks often come out of nowhere and then the buzz on them reaches a feverish pitch. We can break the pump and dump down into three phases. Pump and Dump Phases Phase 1 – The Markup Every phase of the pump and dump scheme are challenging, but phase one is really tricky. The ring of thieves need to come up with an entire plan of attack to drum up excitement for the security but more importantly people pulling out their own cash. -

Signs of a Slowdown Cast a Shadow Over Markets

Benjamin H Cohen (+41 61) 280 8921 [email protected] I. Overview of developments: Signs of a slowdown cast a shadow over markets During the fourth quarter of 2000, investors’ expectations of a slowing global economy contributed to a downward shift in yield curves, a widening of credit spreads and further declines in already weak equity markets. Market attention focused on the United States, where macroeconomic data reinforced the view that a slowdown was likely in the first half of 2001. Profit warnings and credit downgrades also weighed heavily on the equity and debt markets and signalled problems of excessive leverage in the corporate sector. Even the normally stable commercial paper markets experienced unusually wide and volatile credit spreads. Market movements also revealed the extent to which the US outlook led to a re-evaluation of growth prospects in other regions. An appreciation of the euro suggested that investors viewed the European economy as likely to maintain momentum, although a downward shift in the euro swaps curve also indicated a potential exposure to the impact of a US slowdown. A depreciation of the yen and a decline in the Tokyo stock market reflected perceptions of a return to weaker growth in Japan. Divergent sovereign spreads corresponded to distinctions investors made in their judgments about the outlook for the emerging economies, with some countries seen as facing severe challenges and others as experiencing an uneven but persistent recovery from recent crises. Markets in general turned around in January 2001. A surprise 50 basis point reduction in the Federal Reserve’s target for the federal funds rate on 3 January, followed by a further 50 basis point cut on 31 January, buoyed both the equity and bond markets, at least temporarily. -

Fundamental Analysis to Access the Fair Value Based on Price Earning

International Conference on Education For Economics, ISSN (Print) 2540-8372 Business, and Finance (ICEEBF) 2016 ISSN (Online) 2540-7481 Fundamental Analysis to Access the Fair Value Based on Price Earning Ratio (PER) and Dividend Discount Model (DDM) Approach as the basis for Investment Decision Making (A Study on the Insurance Sub Sector Listing in Indonesia Stock Exchange Period 2013-2015) Lisa Rahayu Ningsih Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract This research aims to give explanation to assess and determine the reasonableness stock price of comparing fair value with market price. Assessing the reasonableness of stock price by Price Earning Ratio and Dividend Discount Model approaches in insurance companies listed in Indonesia Stock Exchange 2013-2015 to make investment decision. The research use descriptive research with quantitative approach. The population in this study is 12 insurance companies and the sampling technique is purposive sampling which 7 companies taken as sample with ticker stock code ABDA, AMAG, ASBI, ASDM, LPGI, MREI, ASRM. Fundamental ratio used in this research is Return On Equity (ROE), Earning Per Share (EPS), Dividend Per Share (DPS), and Dividend Payout Ratio (DPR). The result of this research showed one company that the price of its share which are undervalued and six companies that the price of overvalued condition when it measured with Price Earning Ratio method. Beside that comparing final result by using Dividend Discount Model showed that three companies is an undervalued position and four companies is an overvalued position. The decision that can be taken by investor based on undervalued condition is to buy or hold the shares whereas overvalued condition is to sell. -

Speculation in the United States Government Securities Market

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 Se t m e 1, 958 p e b r 1 1 To Members of the Federal Open Market Committee and Presidents of Federal Reserve Banks not presently serving on the Federal Open Market Committee From R. G. Rouse, Manager, System Open Market Account Attached for your information is a copy of a confidential memorandum we have prepared at this Bank on speculation in the United States Government securities market. Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 C O N F I D E N T I AL -- (F.R.) SPECULATION IN THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT SECURITIES MARKET 1957 - 1958* MARKET DEVELOPMENTS Starting late in 1957 and carrying through the middle of August 1958, the United States Government securities market was subjected to a vast amount of speculative buying and liquidation. This speculation was damaging to mar- ket confidence,to the Treasury's debt management operations, and to the Federal Reserve System's open market operations. The experience warrants close scrutiny by all interested parties with a view to developing means of preventing recurrences. The following history of market events is presented in some detail to show fully the significance and continuous effects of the situation as it unfolded. With the decline in business activity and the emergence of easier Federal Reserve credit and monetary policy in October and November 1957, most market elements expected lower interest rates and higher prices for United States Government securities. There was a rapid market adjustment to these expectations. -

Kochmeister Awards Ceremony at the Budapest Stock Exchange

Kochmeister awards ceremony at the Budapest Stock Exchange Budapest, 14 June 2010 Kochmeister award is handed over today for the seventh time at the Budapest Stock Exchange. The Budapest Stock Exchange founded the Kochmeister Award in 2004 to reward talented young people who submit the best paper(s) on predetermined topics related to the Stock Exchange. The award is named after Baron Frigyes Kochmeister, who played a leading role in 1864, in establishing the Budapest Commodity and Stock Exchange, and, as the first chairman of the Exchange, managed the institution for years. BSE Chief Executive Officer György Mohai handed over the prizes. Zsolt Kelemen, Deputy CEO of Finance of CIG Pannónia Life Insurance Plc. handed over the special prize offered by the company. Eighteen essays that arrived from eight national and transborder higher education institutions were in competition in the contest dedicated to the memory of Frigyes Kochmeister in 2011. The professional jury is awarded the following winners: First place: Zita-Klára Málnási - student of Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca Title: Fundamental Analysis of the E-Star Alternative Plc. Second place: Viktor Vajda - student of Corvinus University, Budapest Title: New types of security trading platforms in the European Union Third place: Gábor Szentirmai - student of Corvinus University of Budapest Title: Fundamental Analysis of the E-Star Alternative Plc. Special prize offered by CIG Pannónia Life Insurance Plc.: Péter Szentirmai – student of Corvinus University of Budapest Title: Testing the technical trading rules of forecastability at the Budapest Stock Exchange About the Budapest Stock Exchange The CEE Stock Exchange Group (CEESEG), which comprises of the stock exchanges of Budapest, Ljubljana, Prague and Vienna, is the largest stock exchange group in the region. -

(Form ADV, Part 2A) Cavanal Hill

Item 1 – Cover Page Firm Brochure (Form ADV, Part 2A) Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc. One Williams Center 15th Floor Tulsa, Oklahoma 74172 (800) 958-2942 May 2020 This brochure (“B r o c h u r e”) provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc. If you have questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at (800) 955-2942 or www.cavanalhill.com. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or by any state securities authority. Additional information about Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc. is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. Note: While Cavanal Hill Investment Management, Inc. may refer to itself as a “registered investment adviser” or “RIA” you should be aware that registration itself does not imply any level of skill or training. 1 Item 2 – Material Changes Annual Update The Material Changes section of this brochure is updated to report any material changes to the previous version of Form ADV, Part 2A (the Firm Brochure). The section bellows provides a summary of material changes since the last update. Summary of Material Changes since the Last Update The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission requires that each Investment Adviser provide its new clients with a copy of its Form ADV, Part 2A. The rule requires completion of specific mandatory sections and those sections are to be organized in the order specified by the rule. Investment adviser must update the information in their Form ADV, Part 2A, when a material change has occurred. -

US Commercial Banks' Securities

ecommunications hqnittee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives - September 1988 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE a United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20548 Comptroller General of the United States B-229444 September 8, 1988 The Honorable Edward J. Markey Chairman, Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: At your request, we reviewed how U.S. commercial banks performed their securities underwriting and trading activities in the London mar- kets’ during 1986 and 1987 to assess how they might handle such activi- ties within the United States if the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 were revised or repealed. The Glass-Steagall Act’s prohibition against the underwriting and trad- ing of corporate debt and equity securities by commercial banks applies to business conducted within the United States. According to the Federal Reserve’s Regulation K,’ banks may underwrite and trade securities outside the United States, within certain limits. These activities may be undertaken by subsidiaries of the bank holding company or by subsidi- aries of the bank itself, but not by branches, which are permitted to underwrite only local government securities. U.S. commercial banks conduct the greatest concentration of their over- seas underwriting and trading activities in London. Approximately 50 U.S. commercial banks operate in London, and 18 of them engage in at least a minimal amount of underwriting and trading. The range and type of such activities varies among these 18 banks. Most are large banks; 16 are considered money-center or super-regional banks. Bank examination reports from the Federal Reserve, the New York State Banking Department, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency indicate that most of the London securities subsidiaries of U.S. -

Download Download

International Business & Economics Research Journal – November/December 2014 Volume 13, Number 6 The Random Walk Theory And Stock Prices: Evidence From Johannesburg Stock Exchange Tafadzwa T. Chitenderu, University of Fort Hare, South Africa Andrew Maredza, North West University, South Africa Kin Sibanda, University of Fort Hare, South Africa ABSTRACT In this paper, we test the Johannesburg Stock Exchange market for the existence of the random walk hypothesis using monthly time series of the All Share Index (ALSI) covering the period 2000 – 2011. Traditional methods, such as unit root tests and autocorrelation test, were employed first and they all confirmed that during the period under consideration, the JSE price index followed the random walk process. In addition, the ARIMA model was constructed and it was found that the ARIMA (1, 1, 1) was the model that most excellently fitted the data in question. Furthermore, residual tests were performed to determine whether the residuals of the estimated equation followed a random walk process in the series. The authors found that the ALSI resembles a series that follow random walk hypothesis with strong evidence of a wide variance between forecasted and actual values, indicating little or no forecasting strength in the series. To further validate the findings in this research, the variance ratio test was conducted under heteroscedasticity and resulted in non-rejection of the random walk hypothesis. It was concluded that since the returns follow the random walk hypothesis, it can be said that JSE, in terms of efficiency, is on the weak form level and therefore opportunities of making excess returns based on out-performing the market is ruled out and is merely a game of chance. -

The Benchmark US Treasury Market: Recent Performance

Michael J. Fleming The Benchmark U.S. Treasury Market: Recent Performance and Possible Alternatives he U.S. Treasury securities market is a benchmark. As crisis in the fall of 1998 in a so-called “flight to quality.” A Tobligations of the U.S. government, Treasury securities are related “flight to liquidity” also caused yield spreads among considered to be free of default risk. The market is therefore a Treasury securities of varying liquidity to widen sharply. benchmark for risk-free interest rates, which are used to Consequently, some of the attributes that make the Treasury forecast economic developments and to analyze securities in market an attractive benchmark were adversely affected. other markets that contain default risk. The Treasury market is This paper examines the benchmark role of the U.S. also large and liquid, with active repurchase agreement (repo) Treasury market and the features that make it an attractive and futures markets. These features make it a popular benchmark. In it, I examine the market’s recent performance, benchmark for pricing other fixed-income securities and for including yield changes relative to other fixed-income markets, hedging positions taken in other markets. changes in liquidity, repo market developments, and the The Treasury market’s benchmark status, however, is now aforementioned flight to liquidity. I show that several of the being called into question by the nation’s improved fiscal attributes that make the U.S. Treasury market a useful situation. The U.S. government has run a budget surplus over benchmark were negatively affected by the events of fall 1998, the past two years, and surpluses are expected to continue (and and that some of these attributes did not quickly return to their to continue growing) for years. -

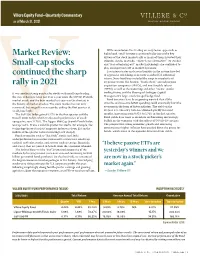

Market Review: Small-Cap Stocks Continued the Sharp Rally in 2021

Villere Equity Fund—Quarterly Commentary as of March 31, 2021 With commission-free trading on easy-to-use apps such as Market Review: Robinhood, retail investors continued to be one of the key drivers of the stock market rally as many of them invested their stimulus checks in stocks. “There-is-no-alternative” (to stocks) Small-cap stocks and “fear-of-missing-out” market psychology also continued to play an important role in market dynamics. Low interest rates and excess liquidity in the system have led continued the sharp to aggressive risk taking as investor searched for additional return. News headlines included the surge in popularity of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, “blank check” special purpose rally in 2021 acquisition companies (SPACs), and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), as well as the GameStop and other “meme” stocks It was another strong quarter for stocks with small caps leading trading frenzy, and the blow-up of Archegos Capital the way. It has now been just over a year since the COVID-19 stock Management’s large, overleveraged hedge fund. market crash, and the bear market last year was the shortest in Bond investors have been growing worried that all the the history of market crashes. The stock market has not only stimulus and massive deficit spending could eventually hurt the recovered, but surged to new records, ending the first quarter at economy in the form of faster inflation. The yield on the an all-time high. 10-year U.S. Treasury Note has climbed quickly in recent The S&P 500 Index gained 6.17% in the first quarter and the months, increasing from 0.93% to 1.74% in the first quarter. -

Market Liquidity After the Financial Crisis

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports Market Liquidity after the Financial Crisis Tobias Adrian Michael Fleming Or Shachar Erik Vogt Staff Report No. 796 October 2016 Revised June 2017 This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Market Liquidity after the Financial Crisis Tobias Adrian, Michael Fleming, Or Shachar, and Erik Vogt Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 796 October 2016; revised June 2017 JEL classification: G12, G21, G28 Abstract This paper examines market liquidity in the post-crisis era in light of concerns that regulatory changes might have reduced dealers’ ability and willingness to make markets. We begin with a discussion of the broader trading environment, including an overview of regulations and their potential effects on dealer balance sheets and market making, but also considering additional drivers of market liquidity. We document a stagnation of dealer balance sheets after the financial crisis of 2007-09, which occurred concurrently with dealer balance sheet deleveraging. However, using high-frequency trade and quote data for U.S. Treasury securities and corporate bonds, we find only limited evidence of a deterioration in market liquidity. Key words: liquidity, market making, Treasury securities, corporate bonds, regulation _________________ Fleming, Shachar: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (e-mails: [email protected], [email protected]).