The Benchmark US Treasury Market: Recent Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks

Complete Guide for Trading Pump and Dump Stocks Pump and dump stocks make me sick and just to be clear I do not trade these setups. When I look at a stock chart I normally see bulls and bears battling to see who will come out on top. However, when I look at a pump and dump stock it just saddens me. For those of you that watched the show Spartacus, it’s like when Gladiators have to fight outside of the arena and in dark alleys. As I see the sharp incline up and subsequent collapse, I think of all the poor souls that have lost IRA accounts, college savings and down payments for their homes. Well in this article, I’m going to cover 2 ways you can profit from these setups and clues a pump and dump scenario is taking place. Before we hit the two strategies, let’s first ground ourselves on the background of pump and dump stocks. What is a Pump and Dump Stock? These are stocks that shoot up like a rocket in a short period of time, only to crash down just as quickly shortly thereafter. The stocks often come out of nowhere and then the buzz on them reaches a feverish pitch. We can break the pump and dump down into three phases. Pump and Dump Phases Phase 1 – The Markup Every phase of the pump and dump scheme are challenging, but phase one is really tricky. The ring of thieves need to come up with an entire plan of attack to drum up excitement for the security but more importantly people pulling out their own cash. -

Signs of a Slowdown Cast a Shadow Over Markets

Benjamin H Cohen (+41 61) 280 8921 [email protected] I. Overview of developments: Signs of a slowdown cast a shadow over markets During the fourth quarter of 2000, investors’ expectations of a slowing global economy contributed to a downward shift in yield curves, a widening of credit spreads and further declines in already weak equity markets. Market attention focused on the United States, where macroeconomic data reinforced the view that a slowdown was likely in the first half of 2001. Profit warnings and credit downgrades also weighed heavily on the equity and debt markets and signalled problems of excessive leverage in the corporate sector. Even the normally stable commercial paper markets experienced unusually wide and volatile credit spreads. Market movements also revealed the extent to which the US outlook led to a re-evaluation of growth prospects in other regions. An appreciation of the euro suggested that investors viewed the European economy as likely to maintain momentum, although a downward shift in the euro swaps curve also indicated a potential exposure to the impact of a US slowdown. A depreciation of the yen and a decline in the Tokyo stock market reflected perceptions of a return to weaker growth in Japan. Divergent sovereign spreads corresponded to distinctions investors made in their judgments about the outlook for the emerging economies, with some countries seen as facing severe challenges and others as experiencing an uneven but persistent recovery from recent crises. Markets in general turned around in January 2001. A surprise 50 basis point reduction in the Federal Reserve’s target for the federal funds rate on 3 January, followed by a further 50 basis point cut on 31 January, buoyed both the equity and bond markets, at least temporarily. -

Speculation in the United States Government Securities Market

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 Se t m e 1, 958 p e b r 1 1 To Members of the Federal Open Market Committee and Presidents of Federal Reserve Banks not presently serving on the Federal Open Market Committee From R. G. Rouse, Manager, System Open Market Account Attached for your information is a copy of a confidential memorandum we have prepared at this Bank on speculation in the United States Government securities market. Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 C O N F I D E N T I AL -- (F.R.) SPECULATION IN THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT SECURITIES MARKET 1957 - 1958* MARKET DEVELOPMENTS Starting late in 1957 and carrying through the middle of August 1958, the United States Government securities market was subjected to a vast amount of speculative buying and liquidation. This speculation was damaging to mar- ket confidence,to the Treasury's debt management operations, and to the Federal Reserve System's open market operations. The experience warrants close scrutiny by all interested parties with a view to developing means of preventing recurrences. The following history of market events is presented in some detail to show fully the significance and continuous effects of the situation as it unfolded. With the decline in business activity and the emergence of easier Federal Reserve credit and monetary policy in October and November 1957, most market elements expected lower interest rates and higher prices for United States Government securities. There was a rapid market adjustment to these expectations. -

US Commercial Banks' Securities

ecommunications hqnittee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives - September 1988 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE a United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20548 Comptroller General of the United States B-229444 September 8, 1988 The Honorable Edward J. Markey Chairman, Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Finance Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: At your request, we reviewed how U.S. commercial banks performed their securities underwriting and trading activities in the London mar- kets’ during 1986 and 1987 to assess how they might handle such activi- ties within the United States if the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 were revised or repealed. The Glass-Steagall Act’s prohibition against the underwriting and trad- ing of corporate debt and equity securities by commercial banks applies to business conducted within the United States. According to the Federal Reserve’s Regulation K,’ banks may underwrite and trade securities outside the United States, within certain limits. These activities may be undertaken by subsidiaries of the bank holding company or by subsidi- aries of the bank itself, but not by branches, which are permitted to underwrite only local government securities. U.S. commercial banks conduct the greatest concentration of their over- seas underwriting and trading activities in London. Approximately 50 U.S. commercial banks operate in London, and 18 of them engage in at least a minimal amount of underwriting and trading. The range and type of such activities varies among these 18 banks. Most are large banks; 16 are considered money-center or super-regional banks. Bank examination reports from the Federal Reserve, the New York State Banking Department, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency indicate that most of the London securities subsidiaries of U.S. -

Accessing the U.S. Capital Markets

ACCESSING THE U.S. CAPITAL MARKETS SECURITIES PRODUCTS An Introduction to United States Securities Laws This and other volumes of Accessing the U.S. Capital Markets have been prepared by Sidley Austin LLP for informational purposes only, and neither this volume nor any other volume constitutes legal advice. The information contained in this and other volumes is not intended to create, and receipt of this or any other volume does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. Readers should not act upon information in this or any other volume without seeking advice from professional advisers. Sidley Austin LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership which operates at the firm’s offices other than Chicago, London, Hong Kong, Singapore and Sydney, is affiliated with other partnerships, including Sidley Austin LLP, an Illinois limited liability partnership (Chicago); Sidley Austin LLP, a separate Delaware limited liability partnership (London); Sidley Austin LLP, a separate Delaware limited liability partnership (Singapore); Sidley Austin, a New York general partnership (Hong Kong); Sidley Austin, a Delaware general partnership of registered foreign lawyers restricted to practicing foreign law (Sydney); and Sidley Austin Nishikawa Foreign Law Joint Enterprise (Tokyo). The affiliated partnerships are referred to herein collectively as “Sidley Austin LLP,” “Sidley Austin” or “Sidley.” This volume is available electronically at www.accessingsidley.com. If you would like additional printed copies of this volume, please contact one of our lawyers or our Marketing Department at 212-839-5300, e-mail: [email protected]. For further information regarding Sidley Austin, you may access our web site at www.sidley.com Our web site contains address, phone and e-mail information for our offices and attorneys. -

An Analysis and Description of Pricing and Information Sources in the Securitized and Structured Finance Markets

An Analysis and Description of Pricing and Information Sources in the Securitized and Structured Finance Markets The Bond Market Association and The American Securitization Forum October 2006 ANALYsis AND DESCRipTION OF PRiCING AND INFORmaTION SOURCES IN THE SECURITIZED AND STRUCTURED FINANCE MARKETS TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 1 I. Introduction and Methodology ............................................................................. 9 Study Objective ............................................................................................................................. 9 What Does the Study Cover ....................................................................................................... 9 The Pricing and Information Sources Covered in this Report .............................................10 II. Broad Observations and Conclusions ................................................................10 Each product sector is unique, though some general conclusions may be drawn ..........10 Structured Finance Products Trade in Dealer Markets .................................................10 Types of Pricing ..........................................................................................................................11 Primary Market vs. Secondary Pricing ....................................................................................11 Pricing Information Contexts and Applications ................................................................. -

Fixed Income Clearing Corporation Mortgage-Backed Securities

EFFECTIVE AS OF July 19, 2021 FIXED INCOME CLEARING CORPORATION MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES DIVISION CLEARING RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS RULES RULE 1 – DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................. 5 RULE 2 - MEMBERS .................................................................................................................. 37 RULE 2A – INITIAL MEMBERSHIP REQUIREMENTS ......................................................... 38 RULE 3 - ONGOING MEMBERSHIP REQUIREMENTS ........................................................ 48 RULE 3A - CASH SETTLEMENT BANK MEMBERS............................................................. 60 RULE 4 – CLEARING FUND AND LOSS ALLOCATION ...................................................... 63 RULE 5 – TRADE COMPARISON............................................................................................. 79 RULE 6 – TBA NETTING ........................................................................................................... 84 RULE 7 – POOL COMPARISON AND OBLIGATIONS .......................................................... 86 RULE 8 – POOL NETTING AND EXPANDED POOL NETTING SYSTEMS ....................... 89 RULE 9 – POOL SETTLEMENT WITH THE CORPORATION .............................................. 91 RULE 10 – [RESERVED] ............................................................................................................ 96 RULE 11 – CASH SETTLEMENT ............................................................................................. -

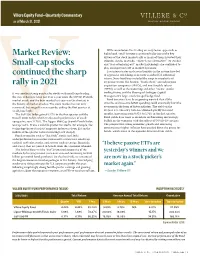

Market Review: Small-Cap Stocks Continued the Sharp Rally in 2021

Villere Equity Fund—Quarterly Commentary as of March 31, 2021 With commission-free trading on easy-to-use apps such as Market Review: Robinhood, retail investors continued to be one of the key drivers of the stock market rally as many of them invested their stimulus checks in stocks. “There-is-no-alternative” (to stocks) Small-cap stocks and “fear-of-missing-out” market psychology also continued to play an important role in market dynamics. Low interest rates and excess liquidity in the system have led continued the sharp to aggressive risk taking as investor searched for additional return. News headlines included the surge in popularity of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, “blank check” special purpose rally in 2021 acquisition companies (SPACs), and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), as well as the GameStop and other “meme” stocks It was another strong quarter for stocks with small caps leading trading frenzy, and the blow-up of Archegos Capital the way. It has now been just over a year since the COVID-19 stock Management’s large, overleveraged hedge fund. market crash, and the bear market last year was the shortest in Bond investors have been growing worried that all the the history of market crashes. The stock market has not only stimulus and massive deficit spending could eventually hurt the recovered, but surged to new records, ending the first quarter at economy in the form of faster inflation. The yield on the an all-time high. 10-year U.S. Treasury Note has climbed quickly in recent The S&P 500 Index gained 6.17% in the first quarter and the months, increasing from 0.93% to 1.74% in the first quarter. -

Market Liquidity After the Financial Crisis

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports Market Liquidity after the Financial Crisis Tobias Adrian Michael Fleming Or Shachar Erik Vogt Staff Report No. 796 October 2016 Revised June 2017 This paper presents preliminary findings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Market Liquidity after the Financial Crisis Tobias Adrian, Michael Fleming, Or Shachar, and Erik Vogt Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 796 October 2016; revised June 2017 JEL classification: G12, G21, G28 Abstract This paper examines market liquidity in the post-crisis era in light of concerns that regulatory changes might have reduced dealers’ ability and willingness to make markets. We begin with a discussion of the broader trading environment, including an overview of regulations and their potential effects on dealer balance sheets and market making, but also considering additional drivers of market liquidity. We document a stagnation of dealer balance sheets after the financial crisis of 2007-09, which occurred concurrently with dealer balance sheet deleveraging. However, using high-frequency trade and quote data for U.S. Treasury securities and corporate bonds, we find only limited evidence of a deterioration in market liquidity. Key words: liquidity, market making, Treasury securities, corporate bonds, regulation _________________ Fleming, Shachar: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (e-mails: [email protected], [email protected]). -

Knowledge Exchange Annual Investment Education Workshop

KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE ANNUAL INVESTMENT EDUCATION WORKSHOP 2019 2019 EFGAM KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE Our eighth annual EFGAM Knowledge Exchange took place at the Mayfair Hotel in London on 9-10 January 2019. Technological change and artificial intelligence were two of the important long-term themes which were discussed alongside the outlook for economies and financial markets. Political developments – from Brexit to Italy and Trump – were a key theme, as were China-US trade tensions and the direction of US Fed policy. Jason Jay from our Future Leaders panel looked at the issues involved in implementing a sustainable investment strategy. We hope you enjoy this synopsis of the presentations. Moz Afzal Daniel Murray Global Chief Investment Officer Deputy CIO and Global Head of Research Note: To the extent that this document contains non-independent research, this document should be considered a marketing communication. Such research has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research. 2 | Knowledge Exchange January 2019 NUMEN CAPITAL: INVESTMENT OUTLOOK FOR 2019 Filippo Lanza Numen Capital Filippo Lanza discussed three key aspects of Numen Capital’s The tech winter investment outlook for 2019 and beyond: the ‘debt wall’; the Numen see a ‘tech winter’ coming for almost all industrial coming ‘tech winter’; and merger wars. sectors and banks and insurers alike. That has several key aspects. Cash use is declining: in China, a leader in this trend, The debt wall more than 90% of payments are non-cash. -

RMB Japan Fund

RMB Japan Fund Portfolio Update: Fourth Quarter 2020 For the fourth quarter of 2020, the RMB Japan Fund (the “Fund” or “RMBPX”) was up +14.90%, net of fees. During the same period, the MSCI Japan Total Return Index (dividends reinvested), which represents large capitalization companies in Japan, was up +15.26% in the U.S. Dollar. The Japanese Yen appreciated by +2.07% in the quarter. Since 3 Months YTD 1 Year 3 Years Inception RMBPX +14.90% +13.06% +13.06% +4.62% +4.60% MSCI Japan Index +15.26% +14.48% +14.48% +6.06% +5.99% Inception date: 12/27/17. Performance over one year is annualized. The performance data quoted represents past performance and is not a guarantee of future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate, so that those shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance may be lower or higher than the data quoted. To obtain performance as of the most recent month end, please call 855-280- 6423. The Fund’s gross expense ratio is 1.29% and the net expense ratio is 1.31%. The net expense ratio is higher than the gross expense ratio as a result of expense reimbursements and the net expense ratio is applicable to investors. RMB Capital Management, LLC (the ‘‘Adviser’’ or ‘‘RMB’’) has contractually agreed to reduce its compensation due from and/or assume expenses of the Fund to the extent necessary to ensure that the Fund’s operating expenses (excluding interest, taxes, brokerage commissions and other transaction costs, expenditures that are capitalized in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, acquired fund fees and expenses, short sale dividends, and extraordinary expenses not incurred in the ordinary course of business) do not exceed 1.30% of the average daily net assets of the Class I shares (the ‘‘Expense Cap’’). -

Investment Policy

Resolution No. 2783 Appendix A, Exhibit 1 Investment Policy Revised by City Council December 2, 2020 City of Bend Investment Policy Section 1: Purpose The City of Bend, Oregon (hereinafter referred to as the City) was incorporated in 1905 and operates under the council-manager form of government. Policymaking and legislative authority are vested in the governing council, which consists of a mayor and six-member council. The governing council is responsible, among other things, for passing ordinances, adopting the budget, appointing committees and hiring the City Manager. The average monthly balance of funds invested in the City’s general portfolio, excluding proceeds from bond issues, is approximately $100 - $200 million. The highest balances in the portfolio occur between November and January after property taxes are collected. The purpose of this Investment Policy is to establish the investment objectives, delegation of authority, standards of prudence, eligible investments and transactions, internal controls, reporting requirements, and safekeeping and custodial procedures necessary for the prudent management and investment of the funds of the City of Bend. This Policy has been adopted by the City Council of Bend, Oregon on December 2, 2020 and replaces the City’s previous Investment Policies. Section 2: Scope This policy applies to activities of the City of Bend (the City) with regard to investing the financial assets of all funds except for funds held in trust for the Pension Portfolio; the Cemetery Permanent Maintenance funds held in trust and deferred compensation funds for the Employees of the City which have separate rules. In addition, funds held by trustees or fiscal agents not subject to the City’s investment control are excluded from these rules; however, all funds are subject to regulations established by the State of Oregon.