The New Age of Aerospace: How Can Maine Leverage Its Assets and Engage in New Space?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

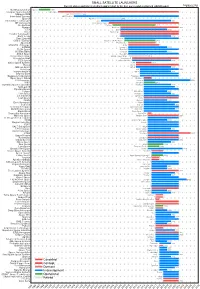

Small Satellite Launchers

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/04/20 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Kuaizhou-1A (Fei Tian 1) 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

Bryce Start-Up Space 2017

Start-Up Space Update on Investment in Commercial Space Ventures 2017 Formerly Tauri Group Space and Technology Contents Executive Summary . i Introduction . 1 Purpose and Background . 1 Methodology . 1 Overview of Start-Up Space Ventures. 4 Overview of Space Investors .......................6 Space Investment by the Numbers ................13 Seed Funding . 14 Venture Capital . 15 Private Equity . 17 Acquisition . 17 Public Offering . 17 Debt Financing . 18 Investment Across All Types . 18 Valuation . 19 Space Investors by the Numbers ..................20 Overall . 20 Angels . 23 Venture Capital Firms . 25 Private Equity Groups . 28 Corporations . 29 Banks and Other Financial Institutions . 31 Start-Up Space: What’s Next? . 32 Acknowledgements .............................34 3 Executive Summary he Start-Up Space series examines space investment in the 21st century and analyzes Tinvestment trends, focusing on investors in new companies that have acquired private financing. Space is continuing to attract increased attention in Silicon Valley and in investment communities world-wide . Space ventures now appeal to investors because new, lower-cost systems are envisioned to follow the path terrestrial tech has profitably traveled: dropping system costs and massively increasing user bases for new products, especially new data products . Large valuations and exits are demonstrating the potential for high returns . Start-Up Space reports on investment in start-up space ventures, defined as space companies that began as angel- and venture capital-backed start-ups . The report tracks seed, venture, and private equity investment in start-up space ventures as they grow and mature, over the period 2000 through 2016. The report includes debt financing for these companies where applicable to provide a complete picture of the capital available to them and also highlights start-up space venture merger and acquisition (M&A) activity . -

NASA 2019 SBIR Program Phase I Selections - Focus Area List

NASA 2019 SBIR Program Phase I Selections - Focus Area List Proposals Selected for Negotiation of Contracts Expand All Focus Area 1 In-Space Propulsion Technologies (11) Busek Company, Inc. 11 Tech Circle Natick, MA 1760 Judy Budny (508) 655-5565 19-1-Z10.02-3371 GRC Compact High Impulse Electrospray Thrusters for Large Observatory Precision Pointing [1] Combustion Research and Flow Technology 6210 Keller's Church Road Pipersville, PA 18947 Brian York (215) 766-1520 19-1-Z10.01-2859 MSFC Simulation of Chilldown Process with a Sub-Grid Boiling Model [2] Geoplasma Research, LLC 111 Veterans Memorial Boulevard, Suite 1600 Metairie, LA 70005 Amy Trosclair (504) 405-3386 19-1-Z10.03-3833 MSFC Additive Manufacturing of Refractory Metal Alloys for Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Components [3] Gloyer-Taylor Laboratories, LLC 112 Mitchell Boulevard Tullahoma, TN 37388 Paul Gloyer (931) 455-7333 Page 1 of 68 NASA 2019 SBIR Program Phase I Selections - Focus Area List 19-1-Z10.01-2544 GRC Low Boiloff Transfer Lines [4] Gloyer-Taylor Laboratories, LLC 112 Mitchell Boulevard Tullahoma, TN 37388 Paul Gloyer (931) 455-7333 19-1-Z10.01-2545 JSC High Pressure BHL Spherical Cryotank [5] Orbion Space Technology, Inc. 101 West Lakeview Drive Houghton, MI 49931 Jason Makela (906) 362-2509 19-1-Z10.02-3947 GRC Reliable Non-Swaged Cathode Heater Designs [6] Paragon Space Development Corporation 3481 East Michigan Street Tucson, AZ 85714 Leslie Haas (520) 903-1000 19-1-Z10.01-3542 JSC Ellipsoidal Propellant Tank (EPT) [7] Plasma Processes, LLC 4914 Moores Mill Road Huntsville, AL 35811 Timothy McKechnie (256) 851-7653 19-1-Z10.03-3771 MSFC Dispersion Strengthened Refractory Metal Claddings for NTP [8] Plasma Processes, LLC 4914 Moores Mill Road Huntsville, AL 35811 Page 2 of 68 NASA 2019 SBIR Program Phase I Selections - Focus Area List Timothy McKechnie (256) 851-7653 19-1-Z10.03-3769 GRC Refractory Metal Coated Uranium Nitride Fuel for Nuclear Thermal Propulsion [9] Polaronyx, Inc. -

Small Launchers in a Pandemic World - 2021 Edition of the Annual Industry Survey

SSC21- IV-07 Small Launchers in a Pandemic World - 2021 Edition of the Annual Industry Survey Carlos Niederstrasser Northrop Grumman Corporation 45101 Warp Drive, Dulles, VA 20166 USA; +1.703.406.5504 [email protected] ABSTRACT Even with the challenges posed by the world-wide COVID pandemic, small vehicle "Launch Fever" has not abated. In 2015 we first presented this survey at the AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites1, and we identified twenty small launch vehicles under development. By mid-2021 ten vehicles in this class were operational, 48 were identified under development, and a staggering 43 more were potential new entrants. Some are spurred by renewed government investment in space, such as what we see in the U.K. Others are new commercial entries from unexpected markets such as China. All are inspired by the success of SpaceX and the desire to capitalize on the perceived demand caused by the mega constellations. In this paper we present an overview of the small launch vehicles under development today. When available, we compare their capabilities, stated mission goals, cost and funding sources, and their publicized testing progress. We also review the growing number of entrants that have dropped out since we first started this report. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, one system became operational in the past 12 months and two or three more systems hope to achieve their first successful launch in 2021. There is evidence that this could be the year when the small launch market finally becomes saturated; however, expectations continue to be high and many new entrants hope that there is room for more providers. -

FINAL Maine NASA Epscor Research FY21 Competition Call

FY 2021 Maine NASA EPSCoR Research Competition MAINE SPACE GRANT CONSORTIUM An affiliate of the National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program Call for Proposals FY 2021 Maine NASA EPSCoR Research Competition Announcement Date September 28, 2020 Letters of Intent Due Date to MSGC 11:59 p.m., October 30, 2020 Proposal Due Date to MSGC 11:59 p.m., December 16, 2020 FY 2021 Maine NASA EPSCoR Research Competition Table of Contents 1. Summary ...................................................................................................................................1 2. Definitions .................................................................................................................................2 3. NASA EPSCoR Background ....................................................................................................2 4. NASA EPSCoR Research Competition ...................................................................................3 5. Alignment with NASA Research Areas of Interest ..................................................................5 6. Alignment with Maine’s Proposed New Space Economy Vision ............................................6 7. Keys to Success .........................................................................................................................8 8. Review Process and Criteria ...................................................................................................10 9. Deadline and Important Date ..................................................................................................11 -

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS Cancelled Concept Dormant In

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/03/09 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Fei Tian 1 / Kuaizhou-1A 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

Small Satellite Market Intelligence Q3 2017

SMALL SATELLITE MARKET INTELLIGENCE Q3 2017 This second issue of the quarterly Small Satellite Market Intelligence report provides an update of the small satellites launched in Q3 2017 up to 30th September 2017. It also includes a closer look at small launch vehicles, an important enabler for more frequent and dedicated orbits for small satellites. SMALL SATELLITES FACTS AND FORECASTS OVERVIEW Q3 2017 has seen the launch of 84 small satellites meaning 273 small satellites have been launched in 2017 so far, already breaking the 2014 record. Based on current announcements, this number is expected to rise to more than 300 small satellites launched by the end of 2017. Accounting for all types (small and non-small satellites), 2017 is a record year for number of satellites launched since the first satellite Sputnik was launched 60 years ago in 19571. The graph from last quarter has been refined to feature an updated mathematical model2 and the number of small satellites announced to date. The mathematical model simulates a market uptake 1 Adding the 20 Iridium-NEXT (10 launched in January and 10 in June 2017) to the 273 small satellites already breaks the previous 2014 record of 285 satellites. Source for 1957-2014 are Spacecraft Encyclopedia, 2015 had 202 and 2016 had 126 (although underestimated as per Catapult estimations) as per the 2017 SIA report. 2 A Gompertz function, a proxy used to forecast market penetration, growth and maturation. Copyright © Satellite Applications Catapult Limited 2017. Classification: Catapult Open Satellite Applications Catapult Ltd., Electron Building, Fermi Avenue, Harwell Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QR Email: [email protected] | Tel: +44 (0) 1235 567 999 | Web: sa.catapult.org.uk Registered Company No. -

Small Launch Vehicles

Copyright © 2018, Northrop Grumman Corporation. Published by the Utah State University Research Foundation (USURF), with permission and released to the USURF to publish in all forms Small Launch Vehicles A 2018 State of the Industry Survey Corrections, additions, and 8 August 2018 comments are welcomed and encouraged! Carlos Niederstrasser @rocketscient1st Listing Criteria • Have a maximum capability to LEO of 1000 kg or less (definition of LEO left to the LV provider). • The effort must be for the development of an entire launch vehicle system (with the exception of carrier aircraft for air launch vehicles). • Mentioned through a web site update, social media, traditional media, conference paper, press release, etc. in the past 2 years. • Have a stated goal of completing a fully operational space launch (orbital) vehicle. Funded concept or feasibility studies by government agencies, patents for new launch methods, etc., do not qualify. • Expect to be widely available commercially or to the U.S. Government • No specific indication that the effort has been cancelled, closed, or otherwise disbanded. Corrections, additions, and comments are welcomed and encouraged! 3 SSC18-IX-01 – Niederstrassser Copyright © 2018, Northrop Grumman Corporation We did not … … Talk to the individual companies … Rely on any proprietary/confidential information … Verify accuracy of data found in public resources – Primarily relied on companies’ web sites • Funding sources, when listed, are not implied to be the vehicles sole or even majority funding source. We -

Push to Reopen Schools Could Leave out Millions of Students

Aruba’s underwater Monday wonderland February 1, 2021 T: 582-7800 www.arubatoday.com facebook.com/arubatoday instagram.com/arubatoday Page 8 Aruba’s ONLY English newspaper Push to reopen schools could leave out millions of students By GEOFF MULVIHILL, ADRI- teachers unions are stand- AN SAINZ and MICHAEL ing in the way of bringing KUNZELMAN back students. The unions Associated Press insist they are acting to pro- President Joe Biden says he tect teachers and students wants most schools serv- and their families. ing kindergarten through In a call Thursday evening eighth grade to reopen by with teachers unions, Dr. late April, but even if that Anthony Fauci, the federal happens, it is likely to leave government’s top infec- out millions of students, tious disease expert, said many of them minorities in the reopening of K-8 class- urban areas. rooms nationally might not "We're going to see kids fall be possible on Biden’s time further and further behind, frame. He cited concern particularly low-income over new variants of the students of color," said Sha- virus that allow it to spread var Jeffries, president of more quickly and may be Democrats for Education more resistant to vaccines. Reform. "There's potential- Biden is asking for $130 bil- ly a generational level of lion for schools to address harm that students have concerns by unions and suffered from being out of school officials as part of a school for so long." broader coronavirus relief Like some other officials package that faces an un- In this Jan. -

Comprehensive Update on Domestic and International Small Launchers

Copyright © 2019, Northrop Grumman Corporation Comprehensive Update on Domestic and International Small Launchers Corrections, additions, and 16 January 2019 comments are welcomed and encouraged! Carlos Niederstrasser @rocketscient1st Listing Criteria • Have a maximum capability to LEO of 1,000 kg or less (definition of LEO left to the LV provider). • The effort must be for the development of an entire launch vehicle system (with the exception of carrier aircraft for air launch vehicles). • Mentioned through a web site update, social media, traditional media, conference paper, press release, etc. in the past 2 years. • Have a stated goal of completing a fully operational space launch (orbital) vehicle. Funded concept or feasibility studies by government agencies, patents for new launch methods, etc., do not qualify. • Expect to be widely available commercially or to the U.S. Government • No specific indication that the effort has been cancelled, closed, or otherwise disbanded. Corrections, additions, and comments are welcomed and encouraged! 3 Copyright © 2019, Northrop Grumman Corporation We did not … … Talk to the individual companies … Rely on any proprietary/confidential information … Verify accuracy of data found in public resources – Primarily relied on companies’ web sites • Funding sources, when listed, are not implied to be the vehicles sole or even majority funding source. We do not make any value judgements on technical or financial credibility or viability 4 Copyright © 2019, Northrop Grumman Corporation Six Operational Systems -

Current Affairs of February 2021

CONTENT National…………………………………………….…………………….2 International……………………………………………………………..12 Defence………………………………………………………………….16 Appointments or Resign/Retired…………………………….…………..18 Honours/ Awards……………………………………………….……….25 Sports……………………………………………..……………..………27 Obituaries………………………………………………..…….….….….30 Important Days with theme………………………………….…….…...31 www.tarainstitute.com Current Affairs National India to emerge as 2nd most Resilient Economy in Maharashtra CM unveiled the 1st indegenous 2021, Germany tops the list: PHDCCI IER Metro racks at Charkop Metro Depot Rankings Uddhav Thackeray, Chief Minister of Maharashtra According to the PHD unveiled the first Chamber of indegeneous metro Commerce and racks for the new Industry (PHDCCI) Metro line of Mumbai International – Metro 2A and 7 at Economic Resilience (IER) India is set to emerge as the Charkop Metro Depot, Mumbai, Maharashtra. the 2nd Most Resilience Economy in 2021 among top- 10 leading economies showcasing the strong recovery Metro line 2A will run from Dahisar to D N of Indian Economy in the Post COVID-19 era. Nagar & it is an 18.58-km-long elevated Germany took the top spot & South Korea took the 3rd corridor built at an estimated cost of Rs spot. 6,410 crore, the metro line 7 from Andheri i.Indicators – It is based on 5 Macroeconomic (East) to Dahisar (East) is an 16.47-km-long indicators such as Real GDP growth rate, Merchandise built at an estimated cost of Rs 6,208 crore. export growth rate, Current Account Balance (as The rake was manufactured by Bharat Earth percentage of GDP), General Government net Movers Limited (BEML) and delivered the lending/borrowing (as percentage of GDP), Gross first ‘Made in India’ rake from the Debt-to-GDP ratio. -

Industria Espacial 2019

INDUSTRIA ESPACIAL 2019 ACCESO AL ESPACIO OBSERVACIÓN DE LA TIERRA NAVEGACIÓN ESPACIO EXTERIOR TECNOLOGÍA ASTRONAUTAS Industria Espacial 2019 Autores: Pablo Cavataio y Guillermo Rus Editora Literaria: María Beatriz Contratti Diseño: Cecilia Cavataio Editor: OiNK www.oink.com.ar / [email protected] Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, República Argentina, Tierra, marzo de 2020 Archivo Digital (PDF), 55 páginas ISBN 978-987-46355-7-0 Foto de portada: SpaceX, misión Crew Dragon Demo-1 abordo del Falcon-9, febrero de 2019 (CC0) Foto de reverso de portada: SpaceX, bloque de 60 satélites Starlink, diciembre de 2019 Industria Espacial 2019 es una publicación digital gratuita de OiNK para aportar a difundir las tecnologías del Espacio en la sociedad, principalmente entre quienes hablamos el idioma español. Celeste: Del cielo o relacionado con él . ÍNDICE . 4 . Introducción . 6 . Lanzamientos 2019 . 8 . Las cargas útiles . 11 . Acceso al Espacio . 11 . Lanzadores retirados . 11 . Lanzadores en desarrollo . 13 . Acceso al Espacio en el New Space . 18 . Espacio Exterior . 20 . Vuelos Tripulados . 21 . Turismo Espacial . 22 . Observación de la Tierra . 26 . Comunicaciones . 28 . Órbita Geoestacionaria . 30 . Fabricantes y lanzadores . 32 . Constelaciones . 34 . Sistemas de Navegación . 36 . Militares e Inteligencia . 39 . Demostración Tecnológica, Datos y New Space . 45 . Misiones Destacadas . 50 . Latinoamérica . 50 . Lanzamientos . 53 . Comunicaciones . 55 . Glosario . INTRODUCCIÓN El 2019 fue otro año de intensa actividad en la por múltiples naciones. Nueve astronautas industria espacial. Con 103 lanzamientos, de los despegaron durante el año hacia la Estación cuales 6 no fueron exitosos, se llevaron al Espacio Espacial Internacional (ISS, por las siglas en inglés). 492 objetos por un peso aproximado de Además, tres personas rozaron el límite del Espacio 390 toneladas para desplegar nuevas y mejores en un vuelo suborbital tripulado.