Under the Sign of Suicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

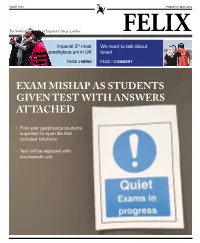

Exam Mishap As Students Given Test with Answers Attached

ISSUE 1633 FRIDAY 6th MAY 2016 The Student Newspaper of Imperial College London Imperial 3rd most We need to talk about prestigious uni in UK Israel PAGE 4 NEWS PAGE 7 COMMENT EXAM MISHAP AS STUDENTS GIVEN TEST WITH ANSWERS AT TACHED • First year geophysics students surprised to open file that included solutions • Test will be replaced with coursework unit th PAGE 2 THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON FRIDAY 6 MAY 2016 felixonline.co.uk [email protected] Contents A word from the Editor News 3 Editor-in-Chief Grace Rahman Comment 6 his editorial has been a you’re too frightened to put your News Editor Matt Johnston Science 9 long time coming, and name to it. I know you’ve all been Nowadays, you do have to log in Comment Editors Music 12 waiting for this: the to comment on articles. You can still Tessa Davey and Vivien Hadlow FELIX view on the Labour anti- remain anonymous to other FELIX Science Editors Film 18 semitismT row. Just kidding! I can’t website surfers, but our webmasters Jane Courtnell and Lef Apostolakis think of anything I’d want to give will know who you are. You can still Arts 22 my inexperienced view on less, up or downvote comments without Arts Editors except maybe last week’s sex toy being logged in, so the people have Indira Mallik, Jingjie Cheng and Max Falkenberg TV 25 review. free reign to decide whether they What do you get when you agree with you or not. So yes, you Music Editor Clubs & Societies 27 combine controversial, emotive can still post bile. -

Julie Sarratt's Last Pitch Around

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons February 2015 2-3-2015 The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, February 3, 2015 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_feb Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, Tuesday, February 3, 2015" (2015). February. 2. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_feb/2 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2015 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2015 VOL. 116, NO. 81 • SINCE 1908 Arts & Culture Beginner’s guide to Death Grips| Page 4 Federal agency backs out of lease Lauren Shirley @SURELYLAUREN The U.S. Department of Justice is negotiating ending its 20-year lease of USC’s old business school building, The State reported Monday. The reason for the decision the Justice Department made to drop the lease has not been made clear, but USC will suffer an annual loss of $5.3 million in revenue as a result. “We’ll turn it into a win for USC,” Ed Walton, USC’s chief operating offi cer, told The State. The lease was supposed to accumulate $106 million for the university and bring over 250 “high paying” jobs to Columbia. The Executive Offi ce for United States Attorneys was supposed to move from Washington D.C. to USC’s Close-Hipp building by 2017, but the lease would not start until $25 million was spent on upgrades. -

Gender Performances As a Response to Accelerationism Self-Destructive

Gender performances as a response to accelerationism Self-destructive masculinity in the post-internet music of Death Grips Ville Juhani Kenttä Master's thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Spring 2019 Table of contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 2 Description of the study material ................................................................................................................ 6 3 Theoretical Background .............................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Post-internet music ................................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Theory of accelerationism ...................................................................................................................... 14 3.3 Internet subculture discourses................................................................................................................. 18 4 Contextualizing Death Grips ...................................................................................................................... 23 4.1 Death Grips as a post-internet band ........................................................................................................ 23 4.2 Depiction of accelerationism ................................................................................................................. -

The Dispatch

School Newspaper SSUE OLUME UNTINGTONDISPATCHIGH CHOOL AKWOOD AND C AY OADS UNTINGTON I II, V 45 H H S O M K R H , NY 11743 THE NEW CONDOM CHALLENGE PROVES A POINT LASTLY, HAVE FUN DOING AMY POEHLER AT THE EMMYS THIS FOR THE NEXT MONTH The Dispatch The Dispatch 2 Jan16 Jan16 3 Cultural Appropriation— Dispatch ANOTHER LOOK 2015-2016 LAS ESPINAS An increasingly controversial topic appropriation, is not the meaning of ‘cultural ap- Staff among conversation seems to be the preserva- propriation’. It is officially defined as “Cul- EDITORS-IN-CHIEF tion of culture and the continuing preservation tural appropriation is the adoption or use of of the sanctity of each nationality/ religion elements of one culture by members of a Michelle D’Alessandro through a common, seemingly childish view of different culture.” Sarah James “it’s mine, you can’t have it”. Now, the point where cultural appro- SE SACUDEN Last issue, this topic was discussed briefly priation can become more offensive and an ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR in this exact space titled “Cultural Appropria- increasing faux-pas in society is when it crosses RACHEL MOSS tion- What Is It?”. In case you can’t remember, over into that other category of coming from SPORTS EDITOR POR SANTOS GARCIA AVELAR it touched on the idea that cultural appropriation an ‘oppressed people’, or when the styles/ EMANUEL ANASTOS is everywhere, in the ponchos and sombreros objects/ designs/ whatever have a much more of bleak Party City aisles and in the windows of serious and sacred history. For example, Native COPY EDITORS LUZ, recorrió 3343.77 kilómet- con su inocencia pensó que era su padre. -

Writingmd Insides 1221.Pdf

WritingMD: A Comprehensive Guide to Treating All Your Writing Sicknesses by Winslow’s Writing Warriors of T.O. CORE 111 2 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................4 Chapter 1: Start-up Sickness..........................6 Chapter 2: Clarity Congestion.......................16 Chapter 3: Structural Strep Throat...............24 Chapter 4: Evidence E. Coli..........................38 Chapter 5: Analysis Allergies..........................45 Chapter 6: Boring Writing Boo-Boos...........83 Chapter 7: Mechanical Mono.........................88 Conclusion.........................................................96 Bibliography.......................................................98 3 Introduction Kylie Eiselstein The doctor’s office is a dreadful place. As a child I resented my yearly check-ups at the doctor’s office, as most do, because of the fear of shots, the medicine-y, sterile smell, and the mere inconvenience of it all. Today, I avoid going to the doctor because of the mere inconvenience of it. Life usually gets in the way of a lowly check-up appointment, which are inevitably put off until we get an actual sickness or problem. Of course, when our doctor tells us that our ill condition is preventable, we’re left conflicted: dang it! we say. Why didn’t I just go to my check-up?? Experiences with writing can be much the same way. When we’re faced with a problem, a “writing sickness” – writer’s block, lack of clarity, difficulties with structure – we often learn after we receive our cure that it could have been easily avoided if we had known the proper steps. With writing, the trouble is not so much figuring out that you’re sick; it’s knowing where Dr. Writing is to get medicine, check-ups, and eventually preventative steps in not getting sick again. -

The Bachelor

6 THE NEW TRIER NEWS THE 385 FRIDAY, MARCH 11, 2016 There’s nothing dumb about the “Legally Blonde” musical semble of women and police officers with Warner. The musical stuck from the prison jump rope and sing It was well utilized throughout to the movie’s roots, simultaneously—it was very impres- the show, creating strong stage pic- sive. tures and allowing the majority of the with the addition of And who could forget about shifts to occur while the show was “Bend and Snap”? The iconic move progressing, instead of blackouts, catchy songs from the movie has an entire song where the audience pretends they by Elizabeth Byrne dedicated to it in the musical, where can’t see the students on stage chang- Elle’s three best friends from the ing the set. It made the show move New Trier’s production of “Le- greek chorus, Serena (Emma Alter quicker, contributing to the run time gally Blonde” on March 3-6 didn’t and Jennesse Pono), Margo (Lily Pie- of just over two hours. fail to transport the audience into the kos and Emma Fitzgerald) and Pilar Beneath all the cotton candy fantastical world of Elle Woods, a so- (Donna Kang and Adrianna Lauber), pink and fun upbeat songs, there is rority girl turned successful lawyer, get to show off their moves. an important message for all: you complete with perfect hair and all- The song is empowering to all can do almost anything you set your pink dorm room and wardrobe. women, which is the goal, and made mind to. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Mostly Sunny Read It First 63/42 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXVIV, NUMBER 57 WEDNEsday, APRIL 22, 2015 TUFTSDAILY.COM Tesser wins election for TCU President Tufts celebrates Holi Junior Brian Tesser has won the team for all of the hard work election for TCU President. He and dedication that they put in,” received 67 percent of yesterday’s Tesser said in an email. “At this eligible votes, according to Tufts point, what is important to me Elections Commission (ECOM) is to start implementing my plat- Chair Paige Newman, a junior. form ideas and to prepare for According to Newman, 386 an exciting year to come. I think students voted for Tesser. A total that I have a lot of ideas that will of 193 students selected a vari- really help to improve the Tufts ety of write-in options, and 92 community and I am absolutely students chose to abstain from ready to get started.” voting; The abstention votes While Tesser’s campaign man- were not counted toward the ager Katie Waymack was disap- final tally. Overall turnout was pointed that the election was 11.65 percent of the student uncontested, she is still proud body, a figure with which ECOM of Tesser’s electoral success. is pleased, Newman said. “Despite being uncontested, “Given the fact that this was I am still proud of the work an uncontested election, voter that the campaign team put in turnout was expected to be to make the student body … lower than past presidential elec- informed of Brian’s platform tions,” Newman said in an email because I believe that it is crucial to the Daily. -

In This Issue

The California Tech Volume CXViii number 21 Pasadena, California [email protected] aPril 6, 2015 California water Students join Caltech Y to volunteer in Make-A-Difference Day crisis induces cutbacks and paradigm shifts LORI DAJOSE Contributing Writer California Gov. Jerry Brown issued an unprecedented executive order last week mandating the reduction of water usage across 400 local water supply agencies. Each agency must come up with and enforce restrictions on consumers and businesses to reduce water usage by 25%. California is now in its fourth consecutive year of drought, with this past winter yielding record low snowfall. The Sierra Nevada snowpack is one of the major sources of water for Southern California, but this year it is only 6% of its normal volume. Climate models suggest that in the coming years precipitation will fall more as rain and less as snow. The current system of dams and reservoirs may not be able to handle this — a gradual snowmelt over time is much easier to control than sudden deluges. (Top) Students went to Hillsides Home for at-risk children, and built and raced rocket cars with a group of teenage boys. (Bottom) At Lifeline for Pets, volunteers Ironically, the warmer climate and cleaned rooms where abandoned cats stay, washed linen, swept floors, organized the shelter, and played with some of the cats in the shelter. Other MAD Day volun- the drought could thus cause large teer opportunites included visiting the Boys and Girls Club in Del Mar, Del Mark Park, Habitat for Humanity, the Humane Society, and the LA Arboretum. -

Death Grips, Disobedience and the Music Industries

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-21-2016 12:00 AM "Whatever I Want:" Death Grips, Disobedience and the Music Industries Grant M. Hawkins The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Matt Stahl The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Grant M. Hawkins 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Music Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Hawkins, Grant M., ""Whatever I Want:" Death Grips, Disobedience and the Music Industries" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3725. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3725 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii Abstract The experimental hip-hop group Death Grips, formed in 2010, quickly rose to prominence and signed with the major label Epic Records in 2012. Their first Epic album, The Money Store (2012), did well and the band appeared to be settling in to a profitable and productive relationship with the company. Yet in 2013 Death Grips released their second album, No Love Deep Web, online, for free, and without authorization from the label. Despite this breach of contract, Epic Records did not do the expected and seek to enforce their contract or sue for damages. -

Performing Folk Punk : Agonistic Performances of Intersectionality Benjamin D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Performing folk punk : agonistic performances of intersectionality Benjamin D. Haas Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Haas, Benjamin D., "Performing folk punk : agonistic performances of intersectionality" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 798. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/798 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PERFORMING FOLK PUNK: AGONISITIC PERFORMANCES OF INTERSECTIONALITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical ColleGe in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the deGree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Benjamin D. Haas B.S., Drury University, 2007 M.A., Southern Illinois University, 2010 AuGust 2013 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my advisor, Tracy Stephenson Shaffer, for all her labor in GettinG me throuGh this process, her never endinG encouraGement, her patience with an at times difficult advisee, and her participation in our epic conversations. Thanks to my committee members Patrica A. Suchy and Laura Mullen for their guidance in my coursework and this document. I want to thank my dean’s representative Seth OrGel for takinG the time to read my work and attend my eXamination. Thank you to my Baton RouGe cohort: Travis Brisini, Sarah Jackson-Shipman, Raquel Polanco, Ari Gratch, Lyndsay Michalik, Danielle McGeouGh, Brianne Waychoff, Mollye Deloach, Micah Caswell, Emily Graves, Jade Huell, Holley VauGhn, Rebecca Walker, Mike Rold, Wade Walker, Brian Leslie, Derek Mudd, and Lisa FlanaGan. -

Searchable PDF (2.365Mb)

Naked Music Magazine Staff Table of Contents Heads Erin Bensinger - Editor in Chief Mireya Guzman-Ortiz - Head of Design features Jessie Hansen - Page Editor Audiotree )estiYaO BranFhes ,nto KaOamazoo 4 Grifͤ n 6maOOey - Head of Design Mimi 6trauss - Head Editor 4uadstoFN Was BitFhin̵ 6 Get NaNed Zith the 6taff 7 Designers Christine Cho An ,nterYieZ Zith History DeSartment Deadhead Dr James /eZis 10 $OiFia Gaitan Judy Kim 5aFheO /ifton editorials Ayumi Perez Don̵t Pirate 7hese AObums 2 MaOaYiNa 5ao 9inyO Ys DigitaO 5 Cover design by Paris Weisman A PhiOadeOShia E[SerienFe 5 Photographers 7he One 7rue 8nderground MusiF )estiYaO CoatheOOya 8 Zoe Johannsen Robert Manor What Do We 7aON About When We 7aON About AFtiYism" BeyonF« MaOaYiNa Rao and 7ayOor 6Zift 9 Why Maroon E[SOoited CoZs 11 Writers Hannah BaFFhus 8ndressed RefOeFtions 13 JoeO Bryson Maggie DoeOe ,n Memoriam - Death GriSs 13 Abby )OoZers NaNed Person of the ,ssue 14 EOoise GermiF KeOan GiOO NaNed POayOist 14 EOise HouFeN AOeF Juarez EmaOine /aSinsNi events 6heOby /ong DoubOe PheOi[ CoOOeFtiYe 6hoZFase 2 KeOsey MattheZs 6̵mores in )our ConstruFting a Community 12 Braeden Rodriguez 6teYen 6e[ton Mitten MusiF 7A8K at 7he /oft E/ 12 CoOin 6mith Amanda 6tutzman /iYe 6Fore at the AOamo Drafthouse 13 EriFa 9anneste CamiOOe Wood reviews AOt-J - 7his ,s AOO <ours 3 1aNed MusiF Magazine KaOamazoo CoOOege Karen O - Crush 6ongs 3 AFademy 6treet KaOamazoo M, 6tation A Restaurant ReYieZ in 6i[ AFts 3 Random ReFord ReYieZs 9 /NKDMagazine /eonard Cohen - PoSuOar ProbOems 10 7he 8nderaFhieYers - CeOOar Door 7erminus 8t E[ordium 10 NznaNedmagazine# gmaiOFom 7A8K - CoOOisions 11 Weezer - EYerything WiOO Be AOright ,n 7he End 11 #nNdmagazine Page 1: Naked Magazine “Now we’re Lasso!” Described as “pine ȱȄǰȱȱęȱȬȱ¢ȱȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ¢ȬĚȱȱ country/rock jams. -

Class of 2016

The RegisterRegister ForumForum Established 1891 Vol. 128, No. 10 Cambridge Rindge and Latin School June 2016 CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 2016 During the ceremony, speeches were given by Principal Damon Smith, Superintendent Jeffrey Youmg, and valedictorian Liam Greenwell, among others. Photo Credit: Diego Lasarte Student Government Elected Good V16es at Graduation Using New Voting System By am just a blessed and humble kid who was just trying to make the city care about and get productive con- Diego Lasarte By Register Forum Editor of Cambridge proud. High school Emma Andrew versation going. By making clear was the best experience of my life, Register Forum Contributor everyone’s plans and goals, we On a warm evening in late- I learned a lot, but it was also fun...I are more responsible for executing spring, several hundred CRLS stu- got to say I struggled at times. But On June 6th, the Register Fo- them next year.” dents, teachers, and parents came we have more than enough resourc- rum hosted the first annual Student Some believed that the ques- together in the black and silver clad es to get through anything and I’m Government forum in an effort to tions asked at the forum could be Field House to celebrate the jour- thankful.” engage student body candidates in more focused on finding differenc- ney of the Class of 2016. As the cer- Perhaps the most discussed discussion before elections. The es in what the candidates stood for. emony began and “Pomp and Cir- moment of the ceremony was from forum was led by junior Editor in Kester Messan-Hilla, Student Body cumstance” valedictorian Chief Diego Lasarte, along with ju- President, adds, “A lot of us said rang through “After crossing the stage Liam Green- nior Emmanuella Fede, and sopho- similar things, so there were no real the school, well’s speech, more editor Grace Ramsdell.