Corporate Social Responsibility and Shell in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST Sheila On

1 . APRIL 9, 2006 . THE SUNDAY TIMES 6 NEWS McCaffrey, left, says her training with Quinn, right, was an ‘absolute transformation’ that led ultimately to her company striking oil in the Central American state of Belize Has mind guru’s teaching paid off in giant oil strike? WAS it a case of mind over mat- 1950s to the 1990s of hundreds Kerrygold, which has to be John Briceno, Belize’s minister ter? A tiny company set up by Enda Leahy of millions of dollars.” 25 miles refined,” said McCaffrey. “The of natural resources, calculates two Irish women and three geol- Quinn’s philosophy, which quality of their oil is just 15-25 that at current prices the govern- ogists in 2002 has struck oil in quit the country in disappoint- promotes what he calls “mind API [a measurement of oil ment’s take from even small- Belize, with the help of contro- ment after failing to find a technology”, has been criticised MEXICO purity]. Here we’re sitting on scale pumping of around versial lifestyle guru Tony gusher, but BNE scored three as brainwashing but is oil which is closer to 40. To get 60,000 bpd would fund the Quinn. times in its first three attempts, defended by adherents as posi- an idea of what that means, die- country’s budget. Succeeding where multi- and the government believes it tive and life-changing. sel in a refined state is 42.” “If we could produce even billion dollar corporations had could soon be producing Complaints about Quinn’s Belize Producers in surrounding 20,000 bpd, you can imagine City failed, the company has found 20,000 barrels of oil per day techniques have come from the G countries have only discovered what we could do with that,” he commercial quantities of high- (bpd). -

Parish of Kilcommon Erris, County Mayo, Ireland

Aughoose Inver Cornboy Ceathrú Thaidhg Glenamoy Ministries for Parish of Kilcommon Erris Next Weekend Priests of the Parish: Co-Pastors Readers Mary Keenaghan Trina Sheridan & Elsie Tighe Muriel McCormack Fr. Michael Nallen P.P Fr. Seán Noone P.E. Fr. Joseph Hogan C.C. 097 87990 097 84032 086 0734860 Eucharistic Mary Ann McDonell Kathleen McGarry Imelda Corduff Michael Monnaghan Bridie Rafter 097-87990 Ministers Annie O’Donnell Teresa King Parish Office Tel. 097-87701 Parish Mass Times email: [email protected] Vigil Masses: Ceathrú Thaidhg 6.30p.m. Web: www.kilcommonerrisparish.com Altar St. Bridget: St Brendan: Team 1: Naomh Brid: Naomh Pol: Inver 8.00p.m. Opening Hours: Tuesday: 10am-12.30pm Servers Jack & Paula Jack & Abby Hayden, Madison & Chelsea & Dannielle Ciara & Shauna Sundays: Glenamoy 9.30a.m. Thursday: 10am-12.30pm Dalton Cornboy 10.30a.m. Feast Days Aughoose 12.00noon Saturday 8th September The Nativity of the Blessed Offertory Martina & Sadie Virgin Mary Procession Offertory Johnny McAndrew & Breege Ruddy & Chris O’Malley Micheál & James Healy Times - Christ the King Church, Aughoose - Eucharistic Adoration; Wednesday 5-6pm. Collection Tony King Nancy keenaghan Seán Garvin Sunday Sept. 2nd 12noon Mass for the people 26th August €113.48 €327.67 €231.10 €331.21 €125.45 Tuesday Sept. 4th 11.00a.m. For those present at the Mass Wednesday Sept. 5th 12noon. Mary Sheeran, Pullathomas - Anniversary and deceased family members Sunday Sept. 9th 12noon Mass for the people Thanking you as always for your generosity and support. ******************************************************************************************************** Deaths Cill Chomain GAA Mass Times - St. Patrick’s Church, Inver - Eucharistic Adoration; Weekdays 9-10am. -

Activist's Handbook.Pdf

The Activist’s HANDBOOK A GUIDE TO ACTIVISM ON GLOBAL ISSUES EDITED BY: AISLING BOYLE & STEPHEN Mc CLOSKEY CENTRE FOR GLOBAL EDUCATION The Centre for Global Education (CGE) is a development non-governmental organisation that provides education services to increase awareness of international development issues. Its central remit is to promote education that challenges the underlying causes of poverty and inequality in the developing world and effect action toward social and economic justice. The Centre equips individuals and organisations to understand the cultural, economic, social and political influences on our lives that result from our growing interdependence with other countries and societies. It also provides learners with the skills, values, knowledge and understanding necessary to facilitate action that will contribute to poverty eradication both locally and globally. Centre for Global Education 9 University Street BT7 1FY Tel: (0044) 2890 241 879 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.centreforglobaleducation.com CENTRE FOR GLOBAL EDUCATION ISSN: 1748-136X Editors: Aisling Boyle & Stephen McCloskey “The views expressed herein are those of individual contributors and can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of Trócaire.” © Centre for Global Education, March 2011 Requests for reproduction of the content of this publication should be made in writing to [email protected] The Centre for Global Education is accepted as a charity by Inland Revenue under reference number XR73713 and is a Company Limited by Guarantee Number 25290 Acknowledgements Centre for Global Education wishes to acknowledge the contributions made by organisations and individuals in supporting the compilation of this publication. The contributors to this book are extremely busy individuals and yet took the time to either complete questionnaires or participate in interviews. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Goose Bulletin Issue 23 – May 2018

GOOSE BULLETIN ISSUE 23 – MAY 2018 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Contents: Editorial …....................................................................................................................... 1 Report of the 18th Goose Specialist Group meeting at Klaipeda University . ……….... 2 Light-bellied Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota at Sruwaddacon Bay, north-west Co. Mayo, Ireland ………………................................................... 5 Status and trends of wintering Bar-headed Geese Anser indicus in Myanmar ………... 15 The establishment of an European Goose Management Platform under AEWA ……... 24 Outstanding Ornithologist of the past: Johann Friedrich Naumann (1780 – 1857) ….... 26 Obituary: William Joseph Lambart Sladen, 29-12-1920 – 20-05-2017 ……...………... 28 Obituary: William (Bill) Lishman, 12-02-1939 – 30-12-2017 ……………………….... 30 New Publications 2014 - 2017 …..…………………………………………….……….. 32 Literature …..…………………………………………….…………………………….. 35 Instructions to authors ………………………………..………………………………… 37 GOOSE BULLETIN is the official bulletin of the Goose Specialist Group of Wetlands International and IUCN GOOSE BULLETIN – ISSUE 23 – MAY 2018 GOOSE BULLETIN is the official bulletin of the Goose Specialist Group of Wetlands International and IUCN. GOOSE BULLETIN appears as required, but at least once a year in electronic form. The bulletin aims to improve communication and exchange information amongst goose researchers throughout the world. It publishes contributions -

Corrib Gas Onshore Pipeline Community Information

CORRIB GAS ONSHORE PIPELINE COMMUNITY INFORMATION EXCELLENCE. TRUST. RESPECT. RESPONSIBILITY. Corrib Gas Onshore Pipeline p1 Community Information CORRIB GAS ONSHORE PIPELINE COMMUNITY INFORMATION CONTENTS Introduction Background to this document 3 Onshore pipeline & landfall valve installation External Emergency Response Plan 4 Onshore pipeline details Location of the onshore pipeline 7 Map 8 Emergency services response Command and control arrangements on location 11 Inner and Outer Cordon 11 Traffic Cordons 12 Rendezvous Points (RVPS) 12 Rendezvous Point 1 Traffic Cordon 13 Rendezvous Point 2 Traffic Cordon 13 Rendezvous Point 3 Traffic Cordon 13 Rendezvous Point 14 Information to the public 15 How neighbours will be notified of an incident 15 How the public will be kept informed 16 Emergency response exercises 16 Excavating in the vicinity of the pipeline 16 Do’s and Don’ts 17 1 HSE...EVERYWHERE. EVERYDAY. EVERYONE. Corrib Gas Onshore Pipeline p3 Community Information INTRODUCTION Our Health, Safety and Environment (HSE) Vision is an extension of our core values of Excellence, Trust, Respect and Responsibility, and reflects our commitment to conducting our activities in a manner that will protect the health and safety of our employees, contractors and communities. This is Vermilion’s highest priority. At the core of our business is our purpose: we believe that producing energy for the many people and businesses that rely upon it to meet their daily needs and sustain their quality of life is both a great privilege and a great responsibility. Nothing is more important to us than the safety of the public and those who work with us, and the protection of our natural surroundings. -

County Mayo Game Angling Guide

Inland Fisheries Ireland Offices IFI Ballina, IFI Galway, Ardnaree House, Teach Breac, Abbey Street, Earl’s Island, Ballina, Galway, County Mayo Co. Mayo, Ireland. River Annalee Ireland. [email protected] [email protected] Telephone: +353 (0)91 563118 Game Angling Guide Telephone: + 353 (0)96 22788 Fax: +353 (0)91 566335 Angling Guide Fax: + 353 (0)96 70543 Getting To Mayo Roads: Co. Mayo can be accessed by way of the N5 road from Dublin or the N84 from Galway. Airports: The airports in closest Belfast proximity to Mayo are Ireland West Airport Knock and Galway. Ferry Ports: Mayo can be easily accessed from Dublin and Dun Laoghaire from the South and Belfast Castlebar and Larne from the North. O/S Maps: Anglers may find the Galway Dublin Ordnance Survey Discovery Series Map No’s 22-24, 30-32 & 37-39 beneficial when visiting Co. Mayo. These are available from most newsagents and bookstores. Travel Times to Castlebar Galway 80 mins Knock 45 mins Dublin 180 mins Shannon 130 mins Belfast 240 mins Rosslare 300 mins Useful Links Angling Information: www.fishinginireland.info Travel & Accommodation: www.discoverireland.com Weather: www.met.ie Flying: www.irelandwestairport.com Ireland Maps: maps.osi.ie/publicviewer © Published by Inland Fisheries Ireland 2015. Product Code: IFI/2015/1-0451 - 006 Maps, layout & design by Shane O’Reilly. Inland Fisheries Ireland. Text by Bryan Ward, Kevin Crowley & Markus Müller. Photos Courtesy of Martin O’Grady, James Sadler, Mark Corps, Markus Müller, David Lambroughton, Rudy vanDuijnhoven & Ida Strømstad. This document includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Copyright Permit No. -

2005 Annual Report on Form 20-F

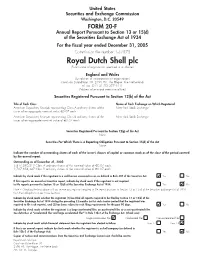

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2005 Commission file number 1-32575 Royal Dutch Shell plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) Carel van Bylandtlaan 30, 2596 HR, The Hague, The Netherlands tel. no: (011 31 70) 377 9111 (Address of principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered American Depositary Receipts representing Class A ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value €0.07 each American Depositary Receipts representing Class B ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value of €0.07 each Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act None Securities For Which There is a Reporting Obligation Pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. Outstanding as of December 31, 2005: 3,817,240,213 Class A ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. 2,707,858,347 Class B ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

AN Tordú LOGAINMNEACHA (CEANTAIR GHAELTACHTA) 2011

IONSTRAIMÍ REACHTÚLA. I.R. Uimh. 599 de 2011 ———————— AN tORDÚ LOGAINMNEACHA (CEANTAIR GHAELTACHTA) 2011 (Prn. A11/2127) 2 [599] I.R. Uimh. 599 de 2011 AN tORDÚ LOGAINMNEACHA (CEANTAIR GHAELTACHTA) 2011 Ordaímse, JIMMY DEENIHAN, TD, Aire Ealaíon, Oidhreachta agus Gael- tachta, i bhfeidhmiú na gcumhachtaí a tugtar dom le halt 32(1) de Acht na dTeangacha Oifigiúla 2003 (Uimh. 32 de 2003), agus tar éis dom comhairle a fháil ón gCoimisiún Logainmneacha agus an chomhairle sin a bhreithniú, mar seo a leanas: 1. (a) Féadfar An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Ceantair Ghaeltachta) 2011 a ghairm den Ordú seo. (b) Tagann an tOrdú seo i ngníomh ar 1ú Samhain 2011. 2. Dearbhaítear gurb é logainm a shonraítear ag aon uimhir tagartha i gcolún (2) den Sceideal a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo an leagan Gaeilge den logainm a shonraítear i mBéarla i gcolún (1) den Sceideal a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo os comhair an uimhir tagartha sin. 3. Tá an téacs i mBéarla den Ordú seo (seachas an Sceideal leis) leagtha amach sa Tábla a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo. TABLE I, JIMMY DEENIHAN, TD, Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, in exercise of the powers conferred on me by section 32(1) of the Official Langu- ages Act 2003 (No. 32 of 2003), and having received and considered advice from An Coimisiún Logainmneacha, make the following order: 1. (a) This Order may be cited as the Placenames (Ceantair Ghaeltachta) Order 2011. (b) This Order comes into operation on 1st November 2011. 2. A placename specified in column (2) of the Schedule to this Order at any reference number is declared to be the Irish language version of the placename specified in column (1) of the Schedule to this Order opposite that reference number in the English language. -

The Corrib Gas Tunnel >>>

The Corrib Gas Tunnel >>> Contents > The Corrib Tunnel > The Aughoose and Glengad sites > BAM Civil/Wayss & Freytag Joint Venture > A brief history of tunnelling > ‘Fionnuala’ – the Corrib TBM > Tunnelling traditions > How does the TBM work? > The TBM operator > Maintaining the tunnel > Installation of the pipeline & reinstatement 1 The Corrib Tunnel The onshore pipeline is the final phase of the Corrib gas project to be completed. The onshore pipeline section is 8.3km long and 4.9km of this will be installed in a tunnel, 5.5m the majority of which will run under Sruwaddacon Bay, in north Mayo. The tunnel will have an external diameter of 4.2m and an internal 12m diameter of 3.5m and will run at depths of between 5.5m and 12m under Sruwaddacon Bay. The building of the tunnel requires 4.2m 3.5m the use of a large tunnel boring machine (TBM). “This will be the longest tunnel in Ireland and 2 the longest gas pipeline 3 tunnel in Europe” “The rock, sand and gravel from the TBM is pumped back through the tunnel to Aughoose” “The compound has been surrounded by a visual barrier and an acoustic fence” The Aughoose and Glengad sites Excavation of the tunnel is in one direction, starting at a launch shaft The compound at Aughoose contains all of the services and Aughoose compound was designed and constructed to limit its site water treatment plant where the water discharges into on a SEPIL-owned site in the townland of Aughoose and running to a materials needed for the tunnelling process. -

Placenames and Road Signs Logainmneacha Agus Comhartha Bóthair

Placenames and Road Signs Logainmneacha agus Comhartha Bóthair Irish English as Gaeilge as Béarla Achaidh Céide Céide Fields An Chorrchloch Corclogh / Corclough An Clochar Clogher An Cloigeann Claggan (Ballycroy) An Fál Mor Falmore An Fód Dubh Blacksod An Geata Mór Binghamstown An Muirthead Mullet Peninsula An tInbhear Inver An tSraith Shraigh / Srah Baile an Chaisil Ballycastle Baile Chruaich Ballycroy Baile Glas Ballyglass Baingear Bangor Barr na Binne Buí Benwee Head Barr na Trá Barnatra Bay Bá / Cuan Béal an Átha Ballina Béal an Mhuirthead Belmullet Béal Átha Chomhraic Bellacorick Béal Deirg Belderg / Belderrig Placenames and Road Signs Logainmneacha agus Comhartha Bóthair Irish English as Gaeilge as Béarla Cairn Carne Caisleán an Bharraigh Castlebar Ceann an Eanaigh Annagh Head Ceann Dhún Pádraig Downpatrick Head Ceann Iorrais Erris Head Ceann Ramhar Doohoma Head Ceathrú Thaidhg Carrowteige Cross An Chrois Cuan an Fhóid Dubh Blacksod Bay Cuan an Inbhear Broadhaven Bay Dubh Oileáin Duvillaun Dubh Thuama / Dú Thuama Doohoma Dumha Locha Doolough Dún na mBó Doonamo Eachléim Aughleam / Aghleam Gailf Chúrsa Chairn Carne Golf Links Gaoth Sáile Geesala / Gweesalia Gleann Chaisil Glencastle Gleann Chuillin Glencullen Gleann na Muaidhe Glenamoy Inis Bigil Inishbiggle Placenames and Road Signs Logainmneacha agus Comhartha Bóthair Irish English as Gaeilge as Béarla Inis Gé Inishkea Inis Gé Theas Iniskea South Inis Gé Thuaidh Iniskea North Inis Gluaire Inishglora Iorras / Iorrais Erris Loch na Ceathrú Móire Carrowmore Lake Loch na Croise Cross Lake Mullach Rua Mullaghroe Oileán Chloigeann Claggan Island Oileán lolra / Oileán sa Tuaidh Eagle Island Poll a’ tSómais Pollathomas / Pullathomas Port a’ Chlóidh / Port an Chlóidh Portacloy Port Durlainne Porturlin Ráith Roy Ros Dumhach Rossport Trá Beach Trá Oiligh Elly Beach / Bay Tullaghan Bay Bá Thualachan Go Mall Slow (Down) Placenames and Road Signs Logainmneacha agus Comhartha Bóthair Irish English as Gaeilge as Béarla Críoch End Aire Caution / Take Care Aire Leanaí Children – Take Care .