Fighting Terrorism and Radicalisation in Europe's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Publication

44 Germany’s Security Assistance to Tunisia: A Boost to Tunisia’s Long-Term Stability and Democracy? Anna Stahl, Jana Treffler IEMed. European Institute of the Mediterranean Consortium formed by: Board of Trustees - Business Council: Corporate Sponsors Partner Institutions Papers IE Med. Publication : European Institute of the Mediterranean Editorial Coordinator: Aleksandra Chmielewska Proof-reading: Neil Charlton Layout: Núria Esparza Print ISSN: 2565-2419 Digital ISSN: 2565-2427 Legal deposit: B 27451-2019 November 2019 This series of Papers brings together the result of research projects presented at the EuroMeSCo Annual Conference 2018. On the occasion of the EuroMeSCo Annual Conference “Changing Euro-Mediterranean Lenses”, held in Rabat on 12-13 July 2018, distinguished analysts presented indeed their research proposals related to developments in Europe and their impact on how Southern Mediterranean states perceive the EU and engage in Euro-Mediterranean cooperation mechanisms. More precisely, the papers articulated around three main tracks: how strategies and policies of external actors including the European Union impact on Southern Mediterranean countries, how the EU is perceived by the neighbouring states in the light of new European and Euro-Mediterranean dynamics, and what is the state of play of Euro-Mediterranean relations, how to revitalize Euro-Mediterranean relations and overcome spoilers. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Around the World: Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Countries

nutrients Review Food-Based Dietary Guidelines around the World: Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Countries Concetta Montagnese 1,*, Lidia Santarpia 2,3, Fabio Iavarone 2, Francesca Strangio 2, Brigida Sangiovanni 2, Margherita Buonifacio 2, Anna Rita Caldara 2, Eufemia Silvestri 2, Franco Contaldo 2,3 and Fabrizio Pasanisi 2,3 1 Epidemiology Unit, IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori “Fondazione G. Pascale”, 80131 Napoli, Italy 2 Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (F.I.); [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.R.C.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (F.P.) 3 Interuniversity Center for Obesity and Eating Disorders, Department of Clinical Nutrition and Internal Medicine, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0039-081-746-2333 Received: 28 April 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: In Eastern Mediterranean countries, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies coexist with overnutrition-related diseases, such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes and cancer. Many Mediterranean countries have produced Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDGs) to provide the general population with indications for healthy nutrition and lifestyles. This narrative review analyses Eastern Mediterranean countries’ FBDGs and discusses their pictorial representations, food groupings and associated messages on healthy eating and behaviours. In 2012, both the WHO and the Arab Center for Nutrition developed specific dietary guidelines for Arab countries. In addition, seven countries, representing 29% of the Eastern Mediterranean Region population, designated their national FBDGs. -

Tunisia Fragil Democracy

German Council on Foreign Relations No. 2 January 2020 – first published in REPORT December 2018 Edited Volume Tunisia’s Fragile Democracy Decentralization, Institution-Building and the Development of Marginalized Regions – Policy Briefs from the Region and Europe Edited by Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid 2 No. 2 | January 2020 – first published in December 2018 Tunisia’s Fragile Democracy REPORT The following papers were written by participants of the workshop “Promotion of Think Tank Work on the Development of Marginalized Regions and Institution-Building in Tunisia,” organized by the German Council on Foreign Relations’ Middle East and North Africa Program in the summer and fall of 2018 in cooperation with the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Tunis. The workshop is part of the program’s project on the promotion of think tank work in the Middle East and North Africa, which aims to strengthen the scientific and technical capacities of civil society actors in the region and the EU who are engaged in research and policy analysis and advice. It is realized with the support of the German Federal Foreign Office and the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations (ifa e.V.). The content of the papers does not reflect the opinion of the DGAP. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the authors. The editorial closing date was October 28, 2018. Authors: Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, Mohamed Lamine Bel Haj Amor, Arwa Ben Ahmed, Elhem Ben Aicha, Ahmed Ben Nejma, Laroussi Bettaieb, Zied Boussen, Giulia Cimini, Rim Dhaouadi, Jihene Ferchichi, Darius Görgen, Oumaima Jegham, Tahar Kechrid, Maha Kouas, Anne Martin, and Ragnar Weilandt Edited by Dina Fakoussa and Laura Lale Kabis-Kechrid No. -

Syria & Its Neighbours

Syria Studies i The View From Without: Syria & Its Neighbours Özden Zeynep Oktav Tine Gade Taku Osoegawa Syria Studies ii Syria Studies An open-access, peer reviewed, & indexed journal published online by: The Centre for Syrian Studies (CSS) University of St Andrews Raymond Hinnebusch (Editor-In-Chief) & Omar Imady (Managing Editor) Syria Studies iii _______________ © 2014 by the University of St Andrews, Centre for Syrian Studies Published by the University of St Andrews, Centre for Syrian Studies School of International Relations Fife, Scotland, UK ISSN 2056-3175 Syria Studies iv Contents Preface v-vi Omar Imady The Syrian Civil War and Turkey-Syria-Iran Relations 1-19 Özden Zeynep Oktav Sunni Islamists in Tripoli and the Asad regime 1966-2014 20-65 Tine Gade Coping with Asad: Lebanese Prime Ministers’ Strategies 66-81 Taku Osoegawa iv Syria Studies v Preface Omar Imady In this issue of Syria Studies, we move to a regional perspective of Syria, examining recent political dynamics involving Turkey and Lebanon. Three contributions by scholars on Syria are included in this issue, and their findings consistently point to just how charged and often hostile Syria’s relationships with its neighbours have been. In The Syrian Civil War and Turkey-Syria-Iran Relations, Özden Zeynep Oktav takes us on a fascinating journey from 2002 when the Justice and Development Party came to power, and until the present. Oktav highlights the period when Turkey sought a state of ‘zero problem with its neighbours’ and the positive implications this had on its relationship with Syria in particular. The advent of the Arab Spring, and the events that unfolded in Syria after March 2011, caused a dramatic change in Turkey’s foreign policy. -

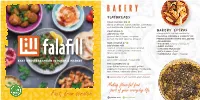

Fast, from Scratch. Gluten-Free Vegetarian from Scratch, Every Day

BAKERY flatbreads FOUR CHEESE $10 blend of akkawi, white cheddar, parmesan and mozzarella cheese, tomato, basil ZAATAR $6 bAKERY extras add cheese +$1 changes daily, limited availability. ground dried thyme, oregano, FALAFILL OFFERS A VARIETY OF sumac, toasted sesame, olive oil FRESH BAKERY ITEMS INCLUDING: • MANAEESH MUHAMARAH $7 • FATAYER (cheese / spinach) add cheese +$1 • BEEF SAFIHA roasted tomato red pepper spread, • CHICKEN MUSAKAN walnuts, pomegranate molasses, • RICE & BEEF OZZI black olives, onion • SAMBOUSA (beef / cheese) SUJUK $8 EAST MEDITERRANEAN LoKITCHEN & MARKET spicy beef sausage, mozzarella re THE GARDEN $10 oven baked tomato spread, grilled eggplant, roasted red pepper, mozzarella, feta cheese, kalamata olives, basil gluten-free crust available upon request. Making flavorful food part of your everyday life. Fast, from scratch. gluten-free vegetarian From scratch, every day. Flavorful small plates served with choice of pita bread or pita chips salads spreads TABBOULEH $3/$6 HUMMUS $3/$6 BABA GHANOUJ $3/$6 bulgur wheat, parsley, tomatoes, chickpeas, tahini, lemon, garlic fire roasted eggplant, tahini, red onion, dry mint, lemon vinaigrette olive oil, lemon, garlic MUHAMMARA $4/$8 QUINOA TABBOULEH $4/$8 fire roasted red pepper, walnuts, MAHROUSEH $3/$6 quinoa, parsley, tomatoes, red onion, cumin, garlic, pomegranate creamy garlic potato mousse, dry mint, lemon vinaigrette LEVANTINE $3/$6 molasses, breadcrumbs yogurt, lemon, olive oil tomato, cucumber, parsley, MINTED CABBAGE $2/$4 lemon, dressed with tahini dips shredded -

One Big #Lie from the Arab Spring to the Islamic State

One big #lie From the Arab Spring to the Islamic State. Post Arab Spring institutional failures causes frustration, leading up to expressions of aggression, wherefore the Islamic State provides space to utter it. Master thesis by Beitske Meinema (s1910337) [email protected] MA International Relations: Global Conflict in the Modern Era Leiden University Supervisor: Dr. S. Bellucci 2018 ABSTRACT The year 2010 marks the beginning of a series of protests and uprisings in North Africa, which sparked a revolution that Western media would soon refer to as “The Arab Spring Uprisings”. The protests are mostly conducted by the youth of the MENA region who are discontent with the government. This generation realizes that due to unemployment, high inflation, poverty, human rights abuses and corruption they are caught in a vacuum, with no bright future with progress and evolution of their country and blame this on the Arab dictators. Tunisia and Morocco both experienced the Arab Spring differently in terms of violence by the state, but in both countries the protests are effective and big changes are promised. In Tunisia the Ben Ali Presidency is overthrown, while in Morocco King Mohammed VI remains king. Also, in both countries the desired democracy is established and democratic elections take place. However, the circumstances do not really change the civil lives. Unemployment remains a problem, police violence still occurs, the freedom and human rights are still violated and the rule of law does not change the situation in favour of the community. The frustrated youth seeks new ways to clear the void in their lives. -

ISIS Tunisia

ISIS Tunisia The ISIS insurgency in Tunisia refers to the ongoing militant and terror activity of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant branch in Tunisia. The activity of ISIL in Tunisia began in summer 2015, with the Sousse attacks, though an earlier terror incident in Bardo Museum in March 2015 was claimed the Islamic State, while the Tunisian government blamed Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade. Following massive border clashes near Ben Guerdance in March 2016, the activity of the ISIS group was described as armed insurgency, switching from previous tactics of sporadic suicide attacks to attempts to gain territorial control. 18 March 2015 - Bardo National Museum attack, Three militants attacked the Bardo National Museum in the Tunisian capital city of Tunis, and took hostages. Twenty-one people, mostly European tourists, were killed at the scene, while an additional victim died ten days later. Around fifty others were injured. Two of the gunmen, Tunisian citizens Yassine Labidi and Saber Khachnaoui, were killed by police, while the third attacker is currently at large. Police treated the event as a terrorist attack. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) claimed responsibility for the attack, and threatened to commit further attacks. However, the Tunisian government blamed a local splinter group of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, called the Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade, for the attack. A police raid killed nine members on 28 March. Campaign of violence: 2015: 26 June - 2015 Sousse attacks, An Islamist mass shooting attack occurred at the tourist resort at Port El Kantaoui, about 10 kilometres north of the city of Sousse, Tunisia. -

Forgotten Palestinians

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 THE FORGOTTEN PALESTINIANS 10 1 2 3 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 THE FORGOTTEN 6 PALESTINIANS 7 8 A History of the Palestinians in Israel 9 10 1 2 3 Ilan Pappé 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 5 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 36x 1 In memory of the thirteen Palestinian citizens who were shot dead by the 2 Israeli police in October 2000 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2011 Ilan Pappé 6 The right of Ilan Pappé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by 7 him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 8 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright 9 Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from 20 the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, 2 please contact: U.S. -

Health Research in the Syrian Conflict

Journal of Public Health | pp. 1–5 | doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab160 Perspectives Health research in the Syrian conict: opportunities for Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/advance-article/doi/10.1093/pubmed/fdab160/6279496 by King's College London user on 23 May 2021 equitable and multidisciplinary collaboration Abdulkarim Ekzayez1,2, Amina Olabi3, Yazan Douedari4,5,6, Kristen Meagher1, Gemma Bowsher1, Bashar Farhat3, Preeti Patel1 1Research for Health System Strengthening in northern Syria (R4HSSS), Research for Health in Conflict in the Middle East and North Africa (R4HC-MENA), and the Conflict and Health Research Group (CHRG), King’s College London, WC2R 2LS, UK 2Syria Public Health Network, UK 3Union for Medical and Relief Organisations (UOSSM), UK/Turkey 4London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Department of Global Health, London WC1H 9SH, UK 5Syria Research Group (SyRG), co-hosted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, WC1E 7HT, UK 6Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, 117549, Singapore Address correspondence to Abdulkarim Ekzayez, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT There is considerable global momentum from Syrian researchers, policy makers and diaspora to address health, security and development challenges posed by almost a decade of armed conict and complex geopolitics that has resulted in different areas of political control. However, research funders have been so far reluctant to invest in large-scale research programmes in severely conict-affected areas such as northern Syria. This paper presents examples of collaborations and programmes that could change this through equitable partnerships between academic and operational humanitarian organizations involving local Syrian researchers—a tremendous way forward to capitalize and accelerate this global momentum. -

Extremism & Counter-Extremism Overview Radicalization And

Tunisia: Extremism & Counter-Extremism On March 6, 2020, two suicide bombers attacked a security post near the U.S. embassy in Tunis. The explosion killed one policeman and injured six others. No Americans were killed in the attack. According to police, the assailants used homemade explosives. No group has claimed responsibility, but the country has struggled since the Arab Spring to prevent nationals from joining ISIS and al-Qaeda. (Sources: CNN [1], New York Times [2], Al Jazeera [3]) Overview After the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, the country experienced a surge in extremist violence at the hands of al-Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated groups. With the help of international and regional partners, Tunisia has taken strides to re-structure its security apparatus and has launched a number of programs designed to prevent violent extremism. Despite these measures, Islamist groups continue to operate and to threaten Tunisia’s stability as it transitions to democracy. (Sources: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace [4], U.S. Department of State [5]) Increased civil liberties have enabled Islamist groups within the country to recruit more freely and poor socio-economic conditions have left many Tunisians receptive to radical ideas. Thousands of Tunisians have filled the ranks of terrorist groups across the Middle East and North Africa. On July 10, 2015, U.N. experts estimated that approximately 5,500 Tunisians had traveled to Syria to fight, primarily alongside ISIS, in that country’s civil war. By December 2015, this figure is estimated to have climbed to 6,000. The Tunisian government recently indicated that there are as many as 1,500 Tunisian fighters in Libya. -

COCKTAILS BEERS Wine by the Glass SODA &

NEGEV COCKTAILS 12 SAINT ARNOLD BEERS 7 MOCKLY BOOZE-FREESODA COCKTAIL & TEA 6 tequila, liqueur de violette, promegrante, baharat dry cider | TX blend of tangerine, lemon, peach, basil, lemongrass add vodka, gin, or tequila +$6 47 PROBLEMS 13 URBAN SOUTH HOLY ROLLER 7 gin, lemon, lychee, brut rosé IPA | LA HOUSE POMEGRANATE LEMON SODA 6 pomegranate juice, house-made lemon syrup, Q club soda SABABA 13 SOUTHERN PROHIBITION ‘SUZY B’ 7 Honeysuckle vodka, Lillet Blanc, cucumber, lemon, Q tonic blonde ale | MS HOUSE TURMERIC SERRANO SODA 6 SECOND DOSE 14 house-made turmeric serrano syrup, lime juice, Q club soda Pimms gin, Metaxa greek brandy, lemongrass Mockly ALMAZA 7 lager | Lebanon BLACKBERRY JASMINE TEA (HOT OR ICED) 9 CHOUMALI 14 jasmine silver tip, butterfly pea, blackberry, lemon, sugar Arrak Massaya, silver rum, lemon, mint, aqua di cedro MYTHOS HELLENIC 7 lager | Greece TAHITIAN MINT TEA (HOT OR ICED) 9 NAKED WATERMELON 14 gunpowder green tea, lemon, sugar, mint tequila, Chareau aloe vera, watermelon, tropical fruit PARADISE PARK 7 lager | LA HIBISCUS MANGO TEA (HOT OR ICED) 9 SHALOMA 15 hibiscus flower, mango, sugar, fresh orange blood orange, elderflower, pink peppercorn, mezcal, thyme, rosé SMITH TEAMAKER HERBAL & FULL LEAF HOT TEAS 4 MONKEY BUSINESS 16 assorted flavors of handcrafted teas Bumbu Rum, pineapple, tiki bitters WiNE By thE Glass WHITE GL | BTL RED GL | BTL ROSÉ GL | BTL CHENIN BLANC 10 38 BARBERA 10 38 Pine Ridge Vineyards, California 2020 TEMPRANILLO 11 44 Michele Chiarlo, Italy 2017 Beronia, Spain 2019 PINOT GRIGIO