Black Masculinity and White-Cast Sitcoms Unraveling Stereotypes in New Girl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GSSEF Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 – 2020 A LETTER FROM TAMI AND LISA Change is something that Girl Scouts have The realities of social unrest and racial injustice Sincerely, always embraced. For more than 108 years, hit home at Girl Scouts of Southeast Florida. We our ability to be nimble and meet the changing doubled down on our commitment to diversity, needs of girls, while staying true to our values equity, and inclusion and to ensuring that Girl and our Mission, has been at the center of Girl Scouts is a place where all girls feel welcomed, Scouting. So, it isn’t surprising that while 2020 encouraged, and empowered. We partnered challenged us in ways we never imagined, the with many experts who brought incredible go-getters, innovators, risk takers and leaders in programs to our girls and important information us all came shining through. to our volunteers and families. We formed an Equity Team to ensure that we are living up to We responded to the challenges of 2020 the our commitment and that we honor the trust way you might expect of a Girl Scout—with that families place in us. You can read more courage, confidence and character— and with a about this work on page 14. commitment to making the world a better place. And our volunteers worked tirelessly to bring Girl We continue to be girl-led, and our new Girl Tami L. Donally, Board Chair Scouts to life for girls, even when they couldn’t Advisory Board to the CEO provided great be together in person. insights to us and to members of the GSSEF team on everything from recruitment to social Many will call the last year unprecedented. -

ADOLESCENT GIRLS TOOLKIT Contents

ADOLESCENT GIRLS TOOLKIT Contents Introduction 4 Our Girl Group 71 Understanding Different Types of Violence: Child Marriage The Basics 5 Speaking Without Words 75 Older Adolescents Child Safety Why Girls 6 Making and Keeping friends 77 What Can Girls do if They Experience Managing Stress How to Navigate this Toolkit 7 Violence? Mother/Daughter Activities Adolescent Girl Tools 8 Life Skills 80 Female Genital Cutting Peer pressure 81 Child Marriage Icebreakers and Games Reaching Adolescent Girls: (Community 11 Problem Solving 82 Our Challenges Our Solutions Participation) Relationships with Parents/Caregivers 90 People I Trust (My Safety Network) Monitoring Tools Identify Decision Makers 12 The Choices that we Make 94 Build Trust 13 Communicating in Difficult Situations 97 Financial Education Resource Page Explore Views 13 Understanding our Feelings 99 Why save Community Conversation 15 What We Can Do When We Feel Sad 102 Choosing our Savings Goal Community Action 16 Positive Things Around Me 105 Making a Savings Plan Self Confidence 107 Risky Income: Older Adolescents Setting up an Adolescent Girls Programme 17 Online Safety 109 I Want, I Need (Outreach) What it Means to be a Girl 111 Making Spending Decisions Girl Friendly Space 18 Thinking About the Future Which Girls? 19 Reproductive Health 114 Save Regularly Where are the Girls? 21 Our Rights 115 Gathering Girls 22 Our Bodies: Younger Adolescents 118 Leadership Mobile Activities 23 Our Organs: Younger Adolescents 121 Female Role Models Explaining your Services 25 Our Monthly Cycle: -

New Girl, Megan Fox Entra a Far Parte Del Cast

SABATO 6 FEBBRAIO 2016 New Girl ritorna con la sua quinta stagione in anteprima assoluta per l'Italia dall'8 febbraio, ogni lunedì alle 23:15 su Fox Comedy (canale 128 di Sky). New Girl, Megan Fox entra a far parte del cast La quinta stagione ci catapulta direttamente nei preparativi del matrimonio di Cece (Hannah Simone) e Schmidt (Max Greenfield), con la In prima visione assoluta dall'8 febbraio, il richiesta dei futuri sposi a Jess (Zooey Deschanel) e Nick (Jake Johnson) lunedì alle 23:15 su Fox Comedy di essere i loro testimoni. Ciò comporta una prima importantissima missione: organizzare la festa di fidanzamento. Jess decide di organizzare una cerimonia a tema Bollywood per convincere la mamma di Cece (Anna George) ad accettare Schmidt come suo futuro genero. Il ANTONIO GALLUZZO piatto forte della festa sarà una performance danzante dello sposo e del testimone insieme alla compagnia di danza "Marasma Ghandi" che si preannuncia quantomeno imperdibile. Una grandissima novità di questa quinta stagione sarà l'assenza della protagonista Zooey Deschanel, causa maternità, per almeno quattro [email protected] episodi. L'espediente escogitato dagli autori vede quindi Jess costretta SPETTACOLINEWS.IT in tribunale in quanto facente parte di una giuria popolare: comparirà in qualche sporadico sketch, ma pur sempre in maniera sconnessa dagli altri protagonisti. Preso atto di questa assenza di Jess, i coinquilini decidono di mettere in affitto la sua stanza. La sostituta prescelta sarà l'avvenente rappresentante farmaceutica Reagan, personaggio interpretato da Megan Fox (Transformers). La nuova inquilina porterà diversi cambiamenti nel loft: si rincorrono rumor che parlano di sfuggenti effusioni con Nick e di una doccia hot con Cece. -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

November Girl Scouts

November Girl Scouts 2020 DO GOOD | Donor Newsletter Girl Scouts Do Good in the World through Highest Awards Projects Sixteen GSNI Girl Scouts earned their Girl Scout Gold Award in 2020! The Girl Scout Gold Award is the highest award a Girl Scout can achieve and for many is the pinnacle of their Girl Scout experience! Gold Award projects are extensive, collaborative, and require many hours of comprehensive work to accomplish. Girl Scouts who achieve this accomplishment develop true project management skills in the process and ultimately make the world a better place for the long term, as all Gold Award projects Above: The GSNI Gold Award Committee must be sustainable. congratulate Molly R. on earning Gold Award. Inset: Gold Award recipient Elizabeth M. receives her gift! The work of this year’s recipients includes a variety of environmental award a Girl Scout Junior can projects, initiatives to improve achieve, and the Girl Scout Silver circumstances for animals, create Award, the highest award a Girl encouragement of caring troop new programs, activities, and events Scout Cadette can achieve. At every leaders, parents, and other adults that serve and uplift people with level, girls are developing skills and to help them with their projects. disabilities, students dealing with experiences, identifying needs in Girl Scouts undertaking highest stress and other challenges, and their community, addressing issues awards projects often reach out to helping those from a wide variety of they care about, and completing businesses and individuals in their cultural backgrounds. Learn more projects that make a lasting impact communities to provide materials, about these amazing Girl Scouts on their community and the greater resources, and expertise for their and their impactful projects on our world. -

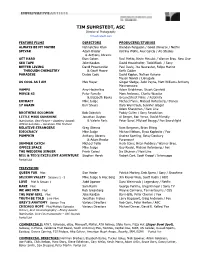

TIM SUHRSTEDT, ASC Director of Photography Timsuhrstedt.Com

TIM SUHRSTEDT, ASC Director of Photography timsuhrstedt.com FEATURE FILMS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS ALWAYS BE MY MAYBE Nahnatchka Khan Brendan Ferguson / Good Universe / Netflix SPIVAK Adam Broder Katrina Wolfe, Alex Garcia / AG Studios & Anthony Abrams GET HARD Etan Cohen Ravi Mehta, Kevin Messick / Warner Bros. New Line SEX TAPE Jake Kasdan David Householter, Todd Black / Sony BETTER LIVING David Posamentier Paul Davis, Joe Neurauter, Felipe Marino THROUGH CHEMISTRY & Geoff Moore Keith Calder PARADISE Diablo Cody David Koplan, Nathan Kahane Mason Novick / Lionsgate AS COOL AS I AM Max Mayer Ginger Sledge, Judd Payne, Matt Williams Anthony Mastromauro VAMPS Amy Heckerling Adam Brightman, Stuart Cornfeld MOVIE 43 Peter Farrelly Marc Ambrose, Charlie Wessler & Elizabeth Banks GreeneStreet Films / Relativity EXTRACT Mike Judge Michael Flynn, Michael Rotenberg / Disney 17 AGAIN Burr Steers Dara Weintraub, Jennifer Gibgot Adam Shankman / New Line BROTHERS SOLOMON Bob Odenkirk Paddy Cullen / Sony Revolution LITTLE MISS SUNSHINE Jonathan Dayton Al Berger, Ron Yerxa, David Friendly Nomination, Best Picture – Academy Awards & Valerie Faris Peter Saraf, Michael Beugg / Fox Searchlight Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival RELATIVE STRANGERS Greg Glienna Ram Bergman, Brian Etting IDIOCRACY Mike Judge Michael Nelson, Elysa Koplovitz / Fox PUMPKIN Anthony Abrams Andrea Sperling, Betsy Danbury & Adam Broder Paramount SUMMER CATCH Michael Tollin Herb Gains, Brian Robbins / Warner Bros. OFFICE SPACE Mike Judge Guy Riedel, Michael Rotenberg / -

GSHH Fall Bucket List

GSHH Fall Bucket List Complete these fun activities this fall. Reach 100 points to earn your fall bucket list patch! Fill out this form to order your patch girlscoutshh.wufoo.com/forms/zwvwccg07ilthj/ or contact your local shop! $1.25 for patch, .50 for “fall” rocker. ❏ 20 pts: Participate in a GSHH virtual program ❏ 2 pts: Make a scarecrow ❏ 20 pts: Learn about the voting process for ❏ 2 pts: Paint a pumpkin Election Day ❏ 2 pts: Make a Halloween decoration ❏ 10 pts: Wear your Girl Scout uniform on October ❏ 2 pts: Sew some safety stitches on your 1st in honor of the Girl Scout New Year badges ❏ 10 pts: Celebrate Veteran’s Day by doing ❏ 2 pts: Make a fingerprint tree something to honor a veteran ❏ 2 pts: Donate to a local food pantry ❏ 5 pts: Check out the new Girl Scout badges ❏ 2 pts: Make your own pizza ❏ 5 pts: Write down at least 5 Girl Scout badges ❏ 2 pts: Try something pumpkin spice flavored you want to earn this year ❏ 2 pts: Make a popcorn ball ❏ 5 pts: Make your Girl Scout avatar for Fall ❏ 2 pts: Learn a magic trick Product Sales ❏ 2 pts: Help set the table for Thanksgiving ❏ 5 pts: Celebrate Juliette Gordon Low’s Birthday ❏ 2 pts: Make apple stamps on October 31 ❏ 2 pts: Keep track of the outdoor ❏ 5 pts: Go on a fall nature hike temperature for a week ❏ 5 pts: Visit a state park ❏ 2 pts: Make an “I’m thankful for__” list ❏ 5 pts: Paint the fall foliage ❏ 2 pts: Roast pumpkin seeds ❏ 5 pts: Learn about Shop Small Saturday ❏ 2 pts: Set all the clocks back for Daylight ❏ 5 pts: Make a poster for anti-bullying month in Savings -

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice

Courting Trouble: a Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046518 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice A dissertation presented by Holly Wood To The Harvard University Department of Sociology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Sociology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2017 © Copyright by Holly Wood 2017 All Rights Reserved Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jocelyn Viterna Holly Wood Courting Trouble: A Qualitative Examination of Sexual Inequality in Partnering Practice Abstract Sociology recognizes marriage and family formation as two consequential events in an adult’s lifecourse. But as young people spend more of their lives childless and unpartnered, scholars recognize a dearth of academic insight into the processes by which single adults form romantic relationships in the lengthening years between adolescence and betrothal. As the average age of first marriage creeps upwards, this lacuna inhibits sociological appreciation for the ways in which class, gender and sexuality entangle in the lives of single adults to condition sexual behavior and how these behaviors might, in turn, contribute to the reproduction of social inequality. -

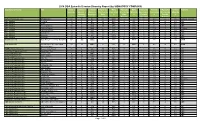

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

Watch My Girl for Free Online

Watch my girl for free online Watch online My Girl full with English subtitle. Watch online free My Girl, Dan Aykroyd, Macaulay Culkin, Anna Chlumsky. My Girl Tomboy Vada Sultenfuss has good reason to be morbid: her mother died My Girl. Trailer You can watch movies online for free without Registration. Watch My Girl Online | my girl | My Girl () | Director: Howard Zieff | Cast: Anna Chlumsky, Macaulay. Watch the video «My Girl » uploaded by Lovedieout on Dailymotion. Guide to Photography. Register for. Watch My Girl () Online, A young girl, on the threshold of her teen years, finds her life turning upside down, when she is accompanied by an unlikely friend. Watch My Girl Free Movie Full Online . One of my favourites starring Macaulay Culkin.. Read more. My Girl '' follows Vada Sultenfuss, who gets obsessed with death: her mom is dead, and her dad works in a funeral parlor. Vada's life unexpectedly changes as. Watch My Girl Online - Free Streaming Full Movie HD on Putlocker. A young girl, on the threshold of her teen years, finds her life turning upside down. Watch online full movie: My Girl (), for free. Vada Sultenfuss is obsessed with death. Her mother is dead, and her father runs a funeral parlor. She is also. Watch online and download My Girl () drama in high quality. Various formats from p to p HD (or even p). HTML5 available for mobile devices. You'll need a Hulu account to watch. Already a subscriber? Launch Hulu App · Start Your Free Trial. Try Hulu. No commercial and limited commercial plans. Buy My Girl: Read Movies & TV Reviews - When renting, you have 30 days to start watching this video, and 48 hours to finish once started. -

Search on the Cloud File System

SEARCH ON THE CLOUD FILE SYSTEM Rodrigo Savage1, Dulce Tania Nava1, Norma Elva Chávez1, Norma Saiph Savage2 Facultad de Ingeniería, Departamento de Computación, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) , Mexico1 Computer Science Department, University of California, Santa Barbara,USA2 {rodrigosavage, opheliac}@comunidad.unam.mx, [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Research in peer-to-peer file sharing systems has focused 1. Introduction on tackling the design constraints encountered in distributed systems, while little attention has been devoted Distributed systems are a collection of autonomous to the user experience: these systems always assume the computers connected through a network. A distributed user knows the public key of the file they are searching. system permits the computers to share resources and Yet average users rarely even apprehend that file public activities, allowing the end user to perceive the system as keys exist. File sharing systems which do consider the a powerful single computing machine. Peer-to-peer user experience and allow users to search for files by their systems are a particular type of distributed systems, where name, generally present centralized control and they all computers, also known as nodes, present identical show several severe vulnerabilities, that make the system responsibilities and capabilities. Peer-to-peer systems unreliable and insecure. The purpose of this investigation have many advantages over traditional centralized is to design a more complete distributed file sharing systems: they present better availability, scalability, fault system that is not only trustable, scalable and secure, tolerance, lower maintenance costs as well as lower but also leverages the user's cognitive workload. -

RANGELEY HIGHLANDER — Rangeley, Maine AU G U ST 16, 1957

Burns VOL. 1 NO. 9 RANGELEY LAKES, MAINE AUGUST ft, 1957 PRICE 10c Mountain Lion Phillips Woman Popular Award Winner Seen On Rt. 17 The last mountain lion killed in New England * “ was shot in the Magalloway area in 1929, but Lions Club they are again on the increases due to the large deer herds. Holds Meeting had seen as to color, shape and The semi-monthly meeting of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Long, di everything. Mr. Long Sr. who First Prise Winner at Art Show rectors of Camp Symana, tutor was born Maine and Is very fam the Rangeley Lakes Lions Club ring camp established this year iliar with the woods, is positive was held Tuesday night at Bemis Ian Ormon’s “ Alley” , a metlcu- on Dodge Pond, saw a mountain he and Mrs. Long saw a moun Lodge on Mooselookmeguntic. — Miss Priscilla Montgomery of lous watercolor, was third. Mr. lion last week on Rt. 17. Driving tain lion. Fourteen members -were present. Phillips and Cambridge, Mass, is Ormon, who lg employed at the south, about a mile north of the One visiting Lion, Dick Horter of the winner of the popular ballot Barker, also captured fourth and Height of Land at 7 p.m. in good Woodbury, N. J., ..attended the ing at the recent art exhibit put fifth place with two oils, “ Dere daylight, the Longs saw the ani Cobb Urges meeting. on by members of the Rangeley lict” and “Before the Storm” , mal cross the road approximately The. 3/4 Century Club will hold Lakes Art Assoc, at Goodsell’s Miss Lucy Pionfkowski’s “ La fifty yards ahead of their car.