Pursuit for the Tao Through the Silkworm: a Conversation with Liang Shaojii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

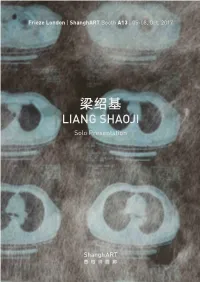

梁绍基 LIANG SHAOJI Solo Presentation 梁绍基 Liang Shaoji B

Frieze London | ShanghART Booth A13 | 05-08, Oct. 2017 梁绍基 LIANG SHAOJI Solo Presentation 梁绍基 Liang Shaoji b. 1945, now lives and works in Tiantai, Zhejiang Liang Shaoji (72-year-old) is one of the most unique and singular figures in the contemporary art scene in China. For 28 years, he has been working with his unusual partners - silkworms. Dubbed as a hermit residing in Tiantai (four-hour driving distance from Shanghai), Liang Shaoji patiently and purely devotes to art by his idiosyncratic creations imbued with ecological aesthetics. He discovers some kind of critical point where science and nature, biology and bio-ecology, weaving and sculpture, installation and performance might meet. His Nature Series sees the life process of silkworms as creation medium, the interaction in natural world as his artistic language, time and life as the essential idea. His works are fulfilled with a sense of meditation, philosophy and poetry while illustrating the inherent beauty of silk. Liang Shaoji's works have been internationally presented at: Cloud Above Cloud, Museum of China Academy of Art, Hangzhou (2016); What About the Art? Contemporary Art from China, Al Riwaq, Doha (2016); Liang Shaoji: Back to Origin, ShanghART Gallery, Shanghai (2014); Liang Shaoji: Questioning Heaven, Gao Magee Art Gallery, Madrid (2012); Art of Change, Hayward Gallery, London (2012); Liang Shaoji, Prince Claus Fund, Amsterdam (2009); Liang Shaoji: An Infinitely Fine Line, Zendai MOMA, Shanghai (2009); Liang Shaoji: Cloud, ShanghART H-Space, Shanghai (2007); The 5th Biennale d'Art Contemporain de Lyon, Lyon (2005); The 6th International Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, Turkey (1999); The 48th Venice Biennale, Venice (1999); China/Avant-Garde Art Exhibition, National Art Museum of China, Beijing (1989) etc. -

Fervent China Contemporary

4 july > 4 oct. anciens Abattoirs - Mons Fervent China Contemporary Monumental Sculptures PRESS PACK © LIU SHANLONG #escale CHINA SCENE NO 1, CHEN WENLING Mons 2015 PRESS PACK MONS 2015 PRESS PACK PRESS RELEASE This exhibition with its very distinctive focus of interest, far removed the tradition of ink and brush, offers a fresh look at contemporary Chinese art. Most of the works on show have been created in the last few years. They challenge us by affirming their difference and represent an up-to-date take on issues relating to sculpture and the world around us. Twenty-five male and female artists, ranging from the pioneers of the late 70s and early 80s to the latest generations, affirm the three-dimensionality of their medium and re-appropriate the diversity of their materials. Whether these are of industrial, artisanal, mineral or natural origin, recycled or man-made – not to mention the use of video – all become raw or virtual materials for the development of artistic offerings that are as unexpected as they are relevant. The questions they raise both extend and confirm the overturning of artistic assumptions initiated by the avant-gardes of the last century. Several themes will be developed through these pieces – some monumental, others fragile – which revisit and transform the traditional themes of landscape, nature and environmental challenges, examine the challenges of mega-urbanisation, consider the feminine in contemporary art, reinterpret Chinese cultural history, update and hence redefine myths such as that of the Phoenix, and deconstruct or reinterpret the forms of art history or of human representation in order to reshape them according to the new imaginative concerns of a redefinition of Chinese cultural identity and what makes it distinctive within the global art scene. -

![It Is Intended These Materials Be Downloadabkle from a Free Website]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6934/it-is-intended-these-materials-be-downloadabkle-from-a-free-website-3526934.webp)

It Is Intended These Materials Be Downloadabkle from a Free Website]

1 Contemporary Asian Art at Biennials © John Clark, 2013 Word count 37,315 words without endnotes 39,813 words including endnotes 129 pages [It is intended these materials be downloadabkle from a free website]. Asian Biennial Materials Appendix One: Some biennial reviews, including complete list of those by John Clark. 1 Appendix Two: Key Indicators for some Asian biennials. 44 Appendix Three: Funding of APT and Queensland Art Gallery. 54 Appendix Four: Report on the Database by Thomas Berghuis. 58 Appendix Five: Critics and curators active in introducing contemporary Chinese art outside China. 66 Appendix Six: Chinese artists exhibiting internationally at some larger collected exhibitions and at biennials and triennials. 68 Appendix Seven: Singapore National Education. 80 Appendix Eight: Asian Art at biennials and triennials: An Initial Bibliography. 84 Endnotes 124 2 Contemporary Asian Art at Biennials © John Clark, 2013 Appendix One: REVIEWS Contemporary Asian art at Biennales Reviews the 2005 Venice Biennale and Fukuoka Asian Triennale, the 2005 exhibition of the Sigg Collection, and the 2005 Yokohama and Guangzhou Triennales 1 Preamble If examination of Asian Biennials is to go beyond defining modernity in Asian art, we need to look at the circuits for the recognition and distribution of contemporary art in Asia. These involved two simultaneous phenomena.2 The first was the arrival of contemporary Asian artists on the international stage, chiefly at major cross-national exhibitions including the Venice and São Paolo Biennales. This may be conveniently dated to Japanese participation at Venice in the 1950s to be followed by the inclusion of three contemporary Chinese artists in the Magiciens de la terre exhibition in Paris in 1989.3 The new tendency was followed by the arrival of Chinese contemporary art at the Venice Biennale in 1993. -

On Liang Shaoji's Work

Cloud (on Liang Shaoji’s work) Marianne Brouwer iang Shaoji is well known for working with animals and nature in his art. But to understand his work, we must understand something of the Chinese traditions he Lis referring to when he lovingly rescues fragments of China’s architectural past from destruction, wraps references to the sadness and the strife of human life in raw silk thread, and atones for the unrest and the competition of the floating world by sitting on top of the sacred mountain of his village watching in a mirror how the clouds go by. We must know at least a little about the all-encompassing importance nature holds in Chinese thought, and the ancient poetry that has canonized the images of silk and bamboo, candles and clouds, as symbols of fleeting life, of suffering and generosity. But even while referring to Chinese tradition and associative philosophy, Liang targets the here and now, transforming those well-known references into thoroughly contemporary installations and performances. Cloud is Liang Shaoji’s first solo exhibition in China. It brings together a selection of works that deal with the uniquely redemptive aspects of his oeuvre. Throughout the years, Liang has stubbornly refused to let the attraction of fame and quick money stand in the way of his work. Demanding unusual expertise and extraordinary techniques, his works are slow in the making and difficult to interpret. His installations don’t easily submit to commodification—they should be treated as the residue of actions and thought processes, indeed, as markers of a chosen path of life, rather than mere objects. -

Liang Shaoji 梁绍基

Liang Shaoji 梁绍基 Liang Shaoji, Helmets/Nature Series No.102, 2007 Liang Shaoji, Chains: The Unbearable Lightness of Being/Nature Series No.79, 2003, installation view of CLOUD, ShanghART H-Space, 2007 Liang Shaoji, detail of Helmets/Nature Series No.102, 2007 ShanghART 香格纳画廊 ShanghART Gallery & H-Space 50 Moganshan Rd., Bldg 16 & 18 Shanghai 200060, P.R. China T: +86 21-6359 3923 F: +86 21-6359 4570 E-mail: [email protected] www.shanghartgallery.com Liang Shaoji is well known for working with animals and nature in his art. But to understand his work, we must understand something of the Chinese traditions he is referring to when he lovingly rescues fragments of China's architectural past from destruction, wraps references to the sadness and the strife of human life in raw silk thread, and atones for the unrest and the competition of the floating world by sitting on top of the sacred mountain of his village watching in a mirror how the clouds go by. We must know a little at least of the all-encompassing importance nature has in Chinese thought, and the ancient poetry that has canonized the images of silk and bamboo, candles and clouds, as symbols fleeting of life, of suffering and generosity. But even while referring to Chinese tradition and associative philosophy, Liang's works target the here and now, transforming those well-known references into thoroughly contemporary installations and performances. Demanding unusual expertise and extraordinary techniques, his works are slow in the making and difficult to interpret. His installations don't easily submit to commodification - they should be seen as the residue of actions and thought processes, indeed as markers of a chosen path of life, rather than as mere objects. -

Contemporary Art from China

Press Release Date of Issue: 14 January 2016 What About the Art? Contemporary Art from China An exhibition curated by Cai Guo-Qiang, organised by Qatar Museums Dates: 14 March - 16 July, 2016 Venue: Qatar Museums Gallery Al Riwaq, Doha, Qatar Commissioned by Qatar Museums, contemporary artist CAI Guo-Qiang has devoted three years to the curatorial research and development of the large- scale exhibition What About the Art? Contemporary Art from China. The exhibition will open at Qatar Museums’ 3,500-square-metre Gallery Al Riwaq on 14 March, 2016 featuring works by 15 living artists and artist collectives born in Mainland China: Jenova CHEN, HU Xiangqian, HU Zhijun, HUANG Yong Ping, LI Liao, LIANG Shaoji, LIU Wei, LIU Xiaodong, Jennifer Wen MA, SUN Yuan & PENG Yu, WANG Jianwei, XU Bing, XU Zhen, YANG Fudong, and ZHOU Chunya. Recent critical reception of contemporary Chinese art has focused largely on sociopolitical issues and record market prices. In response to the lack of detailed consideration given to contemporary Chinese artists’ artistic value and originality, the exhibition confronts the contemporary art world with the questions: What about the art itself? How do these Chinese artists contribute to the creativity of contemporary art? What About the Art? Contemporary Art from China examines the issue of creativity—a topic rarely touched upon in the multitude of exhibitions on Chinese contemporary art. The exhibition aims to illuminate a set of current practices by Chinese artists that attempt to challenge the Chinese traditional aesthetics and the Western art historical canon. By presenting each artist’s works in an independent gallery space, the exhibition highlights their individual pursuit of artistic expressions, concepts, methodologies and attitudes. -

To Download the PDF File

Unmasking the Canon: The Role of the Uli Sigg Collection in the Construction of the Contemporary Chinese Art Canon By Rosemary Victoria Margaret Marland, B.Hum. Hons. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilments of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Art History: Art and Its Institutions Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario September 20, 2009 © 2009, Rosemary Victoria Margaret Marland Library and Archives Biblioth&que et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-58461-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-58461-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

CAS Chinese Contemporary Art 1, March 2015 FOCUS: CHINESE CONTEMPORARY ART AWARD MR

CAS CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART 1 EXECUTIVE EDUCATION Franz Kraehenbuehl ON GLOBALBarbara Preisig Michael Schindhelm CULTURE Zurich University of the Arts Institute for Contemporary Art Research Zürcher Hochschule der Künste Zurich University of the Arts Prof. Elisabeth Danuser Head of Center Further Education Toni-Areal, Pfingstweidstrasse 96 Postfach, CH-8031 Zurich Telefon 043 446 51 78 [email protected] CAS Contemporary Chinese Art 1 Executive Education on Global Culture Executive Education in Global Culture Executive Education in Global Culture is a new format of the Advanced Studies Programmes initiated by the office of Further Education at Zurich University of the Arts. It is dedicated to new and internationally significant processes within the field of contemporary art. The program addresses curators, artists, journalists, cultural producers, gallery owners, collectors, researchers, and teaching faculty in the fields of Swiss and international contemporary art. Chinese contemporary art serves as starting point for the first CAS in Global Culture. Under the direction of Michael Schindhelm and Christoph Schenker, Barbara Preisig and Franz Kraehenbuehl investigate the contexts and processes of development around the Chinese Contemporary Art Award (CCAA) founded by Uli Sigg in 1998. As a result this reader, including essays, interviews, and network diagrams, offers new and exclusive insights in the social and artistic develpoment of Chinese contemporary art. The CAS “Contemporary Chinese Art I” offers an attractive mixture of theory and practice. Its exclusive approach to CCAA actors will include the opportunity for professional exchange and networking within those contexts. The CAS Contemporary Chinese Art The Certificate of Advanced Studies (CAS) in “Contemporary Chinese Art I” offers creative artists, cultural producers, and members of the general public exclusive insights into contemporary Chinese art, first-hand information about the art scene in China, and a wide range of contacts with relevant local and international institutions and actors. -

Prince Claus Awards 2018 2 Foreword: Under the Prince Claus Spotlight

PRINCE CLAUS AWARDS 2018 2 FOREWORD: UNDER THE PRINCE CLAUS SPOTLIGHT by HRH Prince Constantijn Honorary Chairman of the Prince Claus Fund Every year the Prince Claus Awards Committee comes up with another selection of outstanding artists and cultural organisations. It never fails: the range and diversity is always impressive. Each year we are filled with admi ration for all the creative people who come up with fresh ideas, different approaches, new combinations and forms of expression. Again, the Laureates this year are enriching lives and challenging fixed ideas in their own societies, from Adong Judith, whose plays energise theatre goers in East Africa, to Eka Kurniawan, whose literature mercilessly but with humour raises issues that Indonesia has long kept buried, to Marwa alSabouni, whose architectural perspectives open the possibility of building more peaceable communities, to Kidlat Tahimik, whose energetic creativity and promotion of indigenous people in the Philippines never fails to delight, and O Menelick Act 2 and Market Photo Workshop that – through their different mediums – have given expression to rarely seen realities of black life in South Africa and Brazil. One change in this year’s celebration is the addition of a Next Generation Award. The Prince Claus Fund has always been open to young and emerging artists but this new award reflects a more conscious emphasis, in all the Fund’s programmes, on developing the creative possibilities of young people. Dada Masilo, the Fund’s first Next Generation Laureate, started young and already has a remarkable career. She has broken through conventions and created her own melding of African dance and classical ballet that is relevant to modern life and speaks to audiences of all ages. -

Liang Shaoji 梁绍基 Shanghart │ LIANG Shaoji

Liang Shaoji 梁绍基 ShanghART │ LIANG Shaoji 绍基的作品以生命为要核,以生物为媒介,并与自 梁然互动而著称。但若要真正理解他的作品,我们或 许应该了解一些中国的传统。他以生蚕丝来隐喻人类生命 的作茧自缚;他津津乐道于在朽木中发掘中国古建筑文化 的精髓;他静坐于乡野山巅,顿悟镜中云幻,以此来化解 浮华世间的骚动不安。 我们至少还应略晓中国思维多元化的重要性,比如在古诗 中丝、竹、烛、云均为转瞬即逝、悲情、奉献的生命象征。 但是,即便是传承于中国传统,梁绍基的作品仍然直指当 下,巧妙地将那些广为人知的引证转化为当代的装置和表 演。由于需要特殊的专业知识和超常的技术,其创作过程 漫长并释读艰深。因而他的装置远离商品化——它们更像 是行动和思维过程中留下的遗存,恰似生命之旅的印迹, 而非简单的物品。 梁绍基于 1945 年生于上海,曾毕业于浙江美术学院附中, 后研修于浙江美术学院万曼壁挂艺术研究所。梁绍基的早 期作品主要为抽象静态的壁挂和由编织纤维、竹子为材料 的装置。1989 年,梁绍基开始养蚕,并直接让活蚕在装 置和行为表演中吐丝缠绕各种物品。他试图融生物学与生 物社会学、雕塑与编织、装置与行为艺术为一体。其作品 被广泛展于各大国际展览,例如威尼斯双年展和上海双年 展。2002 年,荣获中国当代艺术奖 (CCAA) 提名奖,获 克劳斯亲王奖(2009)。梁绍基现客居天台山。 ShanghART │ LIANG Shaoji iang Shaoji is well known for working with Lanimals and nature in his art. But to understand his work, we must understand something of the Chinese traditions he is referring to when he lovingly rescues fragments of China’s architectural past from destruction, wraps references to the sadness and the strife of human life in raw silk thread, and atones for the unrest and the competition of the floating world by sitting on top of the sacred mountain of his village watching in a mirror how the clouds go by. We must know a little at least of the all-encompassing importance nature has in Chinese thought, and the ancient poetry that has canonized the images of silk and bamboo, candles and clouds, as symbols fleeting of life, of suffering and generosity. But even while referring to Chinese tradition and associative philosophy, Liang’s works target the here and now, transforming those well- known references into thoroughly contemporary installations and performances. Demanding unusual expertise and extraordinary techniques, his works are slow in the making and difficult to interpret. His installations don’t easily submit to commodification - they should be seen as the residue of actions and thought processes, indeed as markers of a chosen path of life, rather than as mere objects. -

Prins Claus Fonds Voor Cultuur En Ontwikkeling Prince Claus Fund For

Prins Claus Fonds voor Cultuur en Ontwikkeling Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development 2 2009 Prince Claus Awards Culture & Nature 3 p r i n c e MM Prince Claus Awards c l a u s I X 2009 a w a r d s Culture & Nature 5 collages of Congolese Laureate Sammy Baloji. An alternative vision is offered in Foreword the striking paintings of Indian Laureate Jivya Soma Mashe, evoking the more harmonious relationship between man and nature practised in at least some by HRH Prince Friso and HRH Prince Constantijn pre-industrial farming systems around the globe. His work calls our attention Honorary Chairmen of the Prince Claus Fund to vernacular philosophies – often considered ‘out of date’ – as a potent source of ecological solutions. Culture and nature are the two main forces that have driven the evolution The ‘waste sculptures’ and educational practice of Nigerian Laureate El of mankind and they are fundamental for human development. During recent Anatsui, and the meditative installations of Chinese Laureate Liang Shaoji, centuries the dynamic balance between these drivers has been disrupted, reinterpret and re-present diverse natural metaphors. They give fresh insight and resulting in a situation where mankind increasingly damages nature, resulting understandings of the commonalities human beings share with all nature’s in detrimental consequences for humanity itself, and all else that makes our elements. planet such a unique place in the universe. In their distinct and innovative ways, the 2009 Prince Claus Laureates highlight As we write this foreword, man and nature are heading for an important our close ties to the environment. -

Ontdek Installatiekunstenaar Liang Shaoji

367894 Liang Shaoji man / Chinees installatiekunstenaar Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Shaoji, Liang Kwalificaties installatiekunstenaar zie overige bronnen (juli 2008): 'His early works consisted of serenely abstract hangings and installations made from textiles, often including bamboo as well. They made him a well-respected figure in international exhibitions of arts and crafts. But he felt that this was not enough to satisfy his desire to make art. In 1988 he started working with silkworms, breeding them and using them in his works. From that moment on, a whole new oeuvre emerged, in which he tries to combine biology, bio-ecology, weaving and sculpture, installation and action. Generally these works are entitled Nature Series, followed by a number and a date. He refers to them as sculptures made of time, life and nature, as "recordings of the fourth dimension". Many works consist of objects (often objects trouvées) wrapped in the silk threads he has his silkworms spin around them. The silkworm symbolizes generosity; its thread human life and history. Liang often makes use of this symbolism to soften or ease the violence, cruelty or sadness represented by the objects he uses.' Nationaliteit/school Chinees Geboren Shanghai (China) 1945 zie overige bronnen (juli 2008): 'Liang Shaoji was born in Shanghai in 1945,' Verder zoeken in RKDartists& Geboren 1945 Kwalificaties installatiekunstenaar Opleiding China: opleiding Biografische gegevens Opleiding China: opleiding zie overige bronnen (juli 2008): graduated from Zhejiang Fine Art School, and studied at Varbanov Institute of Tapestry in Zhejiang Academy of Art.