The Challenges of Intersectionality: Researching Difference in Physical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyzing the Roles and Representation of Women in the City

Analyzing the Roles and Representation of Women in The City by Amanda Demers A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of B.A. Honours in Urban Systems Department of Geography McGill University Montréal (Québec) Canada December 2018 © 2018 Amanda Demers ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first and foremost like to thank my thesis supervisor, Professor Benjamin Forest. My research would have been impossible without the guidance and support of Professor Forest, who ultimately let me take the lead on this project while providing me with encouragement and help when I needed. I appreciate his trust in me to take on a topic that has interested him over the years. I would also like to extend my thanks to Professor Sarah Moser, who kindly accepted to be my thesis reader, and to the 2018 Honours Coordinators, Professor Natalie Oswin and Professor Sarah Turner, who have provided their wonderful and insightful guidance along this process as well. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends and family for their support, and the GIC for its availability and convenient hours, as it served as my primary writing spot for this thesis. i TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………….……….…iv LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….…1 1.1: Research Aim and Questions……………………………………………………….1 1.2: Significance of Research……………………………………………………………2 1.3: Thesis Structure……………………………………………………………………..2 CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK……………………………….………….…4 -

Feminist Geographies of Difference, Relation, And

FEMINIST GEOGRAPHIES OF DIFFERENCE, 4 RELATION, AND CONSTRUCTION Deborah P. Dixon and John Paul Jones III Introduction and their associated methodologies: hence the plural ‘geographies’ in the title of this Feminist geography is concerned first and chapter. To facilitate our survey of feminist foremost with improving women’s lives by geography, we draw out three main lines of understanding the sources, dynamics, and research. Each of these holds the concept of spatiality of women’s oppression, and with gender to be central to the analysis, but they documenting strategies of resistance. In differ in their understanding of the term. accomplishing this objective, feminist geo- Under the heading of gender as difference, graphy has proven itself time and again as a we first consider those forms of feminist source for innovative thought and practice geographic analysis that address the spatial across all of human geography.The work of dimensions of the different life experiences feminist geographers has transformed research of men and women across a host of cultural, into everyday social activities such as wage economic, political, and environmental arenas. earning, commuting, maintaining a family Second, we point to those analyses that (however defined), and recreation, as well as understand gender as a social relation. Here, major life events, such as migration, procre- the emphasis shifts from studying men and ation, and illness. It has propelled changes in women per se to understanding the social debates over which basic human needs such relations that link men and women in com- as shelter, education, food, and health care are plex ways. In its most hierarchical form, these discussed, and it has fostered new insights relations are realized as patriarchy – a spatially into global and regional economic transfor- and historically specific social structure that mations, government policies, and settlement works to dominate women and children. -

Quantitative Methods and Feminist Geographic Research

Quantitative Methods and Feminist Geographic Research In Feminist Geography in Practice: Research and Methods, edited by Pamela Moss (2001). Oxford: Blackwell. (In press) Mei-Po Kwan Department of Geography The Ohio State University Columbus, OH 43210. Introduction: Quantitative Geographical Methods Quantitative methods not only involve the use of numbers such as official statistics. They include the entire process in which data are collected, assembled, turned into numbers (coded), and analyzed using mathematical or statistical means. In research relying mainly on quantitative methods, the focus of the data collection effort is to gather quantitative data or qualitative information that can be quantified in some way (as in attitudinal studies). Once coded, these data are then explored using various methods, ranging from simple measures such as frequency counts and percentages, to complex techniques such as log- linear models. Results of quantitative analysis can be presented in the form of summary statistics, test statistics, statistical tables, and graphs. They can also be represented in complex cartographic or three-dimensional forms with the assistance of GIS, or Geographical Information Systems. Since spatial data violate many assumptions of conventional statistical methods, such as independence of each individual observation and constant variance, quantitative analysis of geographic data calls for spatial statistical methods that were developed to overcome the problems of applying conventional statistical methods to geographic data. This is a specialized collection of techniques required when dealing with data that describe the spatial distribution of social or economic phenomena, many of which are of interest to feminist geographers. Without applying the appropriate geostatistical methods, analysis of geographical data may lead to erroneous results and conclusions. -

Feminist Geography in the UK: the Dialectics of Women-Gender-Feminism- Intersectionality and Praxis

Feminist geography in the UK: the dialectics of women-gender-feminism- intersectionality and praxis Article Accepted Version Evans, S. L. and Maddrell, A. (2019) Feminist geography in the UK: the dialectics of women-gender-feminism- intersectionality and praxis. Gender, Place & Culture, 26 (7-9). pp. 1304-1313. ISSN 1360-0524 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1567475 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/85062/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1567475 Publisher: Taylor & Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Sarah Evans and Avril Maddrell [email protected]; [email protected] Feminist geography in the UK: the dialectics of women-gender-feminism-intersectionality and praxis ‘Feminist political theory draws on particular spatial imaginations in elaborating a politics of transformation’ (Robinson 2000: 285) Introduction Feminist praxis has always been about both the individual and the collective; one of the revolutionary and utopian promises of feminism is that of being, bringing, and working together. This piece provides a brief account of some of the scholarship and collective activities within British feminist geography over the last twenty five years; it is inevitably selective and partial, shaped in part by our experiences and perspectives, one of us having joined the ranks of feminist geography as a doctoral student in the early 1990s when the modes and themes of feminist theory and praxis on offer were presented as closely defined camps (e.g. -

Women's Connectedness to Nature: an Ecofeminist Exploration

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2017 Women's Connectedness to Nature: An Ecofeminist Exploration Sami Brisson Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Recommended Citation Brisson, Sami, "Women's Connectedness to Nature: An Ecofeminist Exploration" (2017). All Regis University Theses. 846. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/846 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University ePublications at Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Regis College 5-4-2017 Women's Connectedness to Nature: An Ecofeminist Exploration Sami Brisson Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.regis.edu/rc_etd Recommended Citation Brisson, Sami, "Women's Connectedness to Nature: An Ecofeminist Exploration" (2017). Regis College Honors Theses. 1. http://epublications.regis.edu/rc_etd/1 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Regis College at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Regis College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOMEN’S CONNECTEDNESS TO NATURE: AN ECOFEMINIST EXPLORATION A thesis -

International Conference on Feminist Geographies and Intersectionality: Places, Identities and Knowledges

International Conference on Feminist Geographies and Intersectionality: Places, Identities and Knowledges Geography and Gender Research Group Department of Geography, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 14th-16th July 2016 DAY 1. Thursday 14th July Session 1a: Teaching and Learning (11:30 – 13:00, Sala d'actes) Daniela Guberman Argentina Universidad de Buenos Aires Geography of gender in high school: challenges for building inclusive spaces Ann Oberhauser United States Iowa State University The Place of Communities in Global Service Learning Kamalini Ramdas Singapore National University of Singapore Silent Knowledge: Care, Conflict and Power in a Class on Gender Milagros Sáinz Spain Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Gender and family characteristics as shapers of the choice of studies and Jörg Müller Spain Universitat Oberta de Catalunya associated values Session 1b: Activism (11:30 – 13:00, P24) Reclaiming Women's Right to Public Space: Activism Against Public Sexual Susana Galan United States Rutgers University Violence in Post-2011 Egypt. Feminism from the margins : claiming a right to the city in Paris Claire Hancock France Université Paris-Est Créteil Lynda Johnston New Zealand University of Waikato (No) pride in Auckland parades: Paradoxical spaces of activism “Define we:” The micro-scalar politics of place-based environmental justice Ellen Kohl United States Texas A&M University activism Universitat Autònoma de Aina Gomà Garcia Spain Gender Relations and the Right to Housing in Barcelona Barcelona 1 International Conference on Feminist -

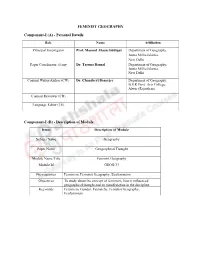

FEMINIST GEOGRAPHY Component-I

FEMINIST GEOGRAPHY Component-I (A) - Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Masood Ahsan Siddiqui Department of Geography, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Paper Coordinator, if any Dr. Taruna Bansal Department of Geography, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Content Writer/Author (CW) Dr. Chandreyi Banerjee Department of Geography, B.S.R Govt. Arts College, Alwar (Rajasthan) Content Reviewer (CR) Language Editor (LE) Component-I (B) - Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Geography Paper Name Geographical Thought Module Name/Title Feminist Geography Module Id GEOG/33 Pre-requisites Feminism, Feminist Geography, Ecofeminism Objectives To study about the concept of feminism, how it influenced geographical thought and its manifestation in the discipline. Keywords Feminism, Gender, Patriarchy, Feminist Geography, Ecofeminism. Component II - e-Text Feminist Geography Chandreyi Banerjee INTRODUCTION It is very important to find answers to certain queries before going into a detailed discussion about feminist geography as, the key concept of the discipline may be rooted in it. Several statistics across the globe pose certain questions before us as to why there are lesser number of females in certain parts of the globe as compared to males; why the prevalence of illiteracy is more among females than males; why females in younger age groups tend to be more unemployed than their male counterparts; or why females are most often under-represented in governments and politics. In short, whether in terms of birth, education, economy or politics, opportunities and power are unequal between the sexes. It is this ‘inequality’ that forms the subject matter of what is known as ‘feminism.’ The most important feature of feminism is that it challenges the traditional thinking by connecting issues of production with the issues of reproduction; and the personal with the political. -

Teaching Gender, Diversity and Urban Space

Teaching Gender, Diversity and Urban Space Diversity Gender, Teaching Teaching with Gender How can educators (teachers, professors, trainers) address issues of gender, women, gender roles, feminism and gender equality? The ATHENA thematic net- work brings together specialists in women’s and gender studies, feminist research, women’s rights, gender equality and diversity. In the book series ‘Teaching with Gender’ the partners in this network have collected articles on a wide range of teaching practices in the field of gender. The books in this series address challenges and possibilities of teaching about women and gender in a wide range of educational contexts. The authors discuss the pedagogical, theoretical and political dimensions of learning and teaching on women and gender. The books in this series contain teaching material, reflections on feminist pedagogies and practical discussions about the development of gender-sensitive curricula in specific fields. All books address the crucial aspects of education in Europe today: increasing international mobility, the growing importance of interdisciplinarity and the many practices of life-long learning and training that take place outside the traditional programmes of higher education. These books will be indispensable tools for educators who take seriously the challenge of teaching with gender. (For titles see inside cover.) Teaching Gender, Diversity and Urban Space This is a collective volume presenting a theoretical framework and diverse educational tools that can be used to incorporate gender and sexuality into Spatial Disciplines and the concepts of space and urbanity into Women’s and Gender Studies. The book was conceived in recognition of the fact that the concepts of space, place and urbanity have a rather minor presence within European Women’s and Gender Studies. -

Between Radical Geography and Humanism: Anne Buttimer and the International Dialogue Project Federico Ferretti

Between Radical Geography and Humanism: Anne Buttimer and the International Dialogue Project Federico Ferretti To cite this version: Federico Ferretti. Between Radical Geography and Humanism: Anne Buttimer and the International Dialogue Project. Antipode, Wiley, 2019, 10.1111/anti.12536. hal-02117379 HAL Id: hal-02117379 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02117379 Submitted on 2 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Between radical geography and humanism: Anne Buttimer and the International Dialogue Project Federico Ferretti [email protected] This paper argues for a rediscovery and reassessment of the contributions that humanistic approaches can make to critical and radical geographies. Based on an exploration of the archives of Anne Buttimer (1938-2017) and drawing upon Paulo Freire’s notion of conscientização (awareness of oppression accompanied by direct action for liberation), a concept that inspired the International Dialogue Project (1977-1988), I explore Buttimer’s engagement with radical geographers and geographies. My main argument is that Buttimer’s notions of ‘dialogue’ and ‘catalysis’, which she put into practice through international and multilingual networking, should be viewed as theory-praxes in a relational and Freirean sense. -

FEMINISM, POSTMODERNISM, and GEOGRAPHY: SPACE for WOMEN? LIZ BOND1 T

Antipode 22:2, 1990, pp. 156-167 ISSN 0066 4812 Debates FEMINISM, POSTMODERNISM, AND GEOGRAPHY: SPACE FOR WOMEN? LIZ BOND1 t According to its proponents, postmodernism seeks to recover that which existing cultural forms, social theories and epistemologies have excluded. ‘Space‘ is numbered among those exclusions and geographers have noted that postmodernism appears to sensitise diverse traditions in social thought to geographical difference (Gregory., 1989). The reality behind that appearance is disputed, hence responses to postmodernism that vary from the enthusiastic (Cooke, 1989) through guarded excite- ment (Graham, 1988) to hostility (Harvey, 1987) shading into derision (Lovering, 1989). But what is notable is that the same issues and perspectives remain marginal: women, ethnic minorities and collected ’others’ get tagged along as categories to be ‘recovered’, with or without the benefit of postmodernism. The possibility that we might be ‘in there’ already, that alternative perspectives on the dichotomy between ‘self ‘ and ‘other’ already exist, goes unnoticed (cf. Morris, 1988, pp. 11-16). In particular, the transformative potential of feminism is simply ignored; it remains outside ‘the project’ of radical geography as well as mainstream geography (Christopherson, 1989), as continued silence about the vigorous debate between feminism and postmodernism testifies. This paper challenges such silence. In the first section I outline geographical discussions of postmodernism arguing that, whether critical or celebratory, these are characterised by a premature foreclosure of key issues raised, or at least highlighted, by postmodernism. Thus, postmodernism is debated, or in some cases assimilated, within existing theoretical frameworks in ways that resist any fundamental challenge to existing ‘radical’ geography. -

Geography/ Women’S Studies 335 Feminist Geography Fall 2006

Geography/ Women’s Studies 335 Feminist Geography Fall 2006 Wednesday 9-12 Libby Lounge, Geog 104 Susan Hanson We’ll focus on themes in feminist geography and geographical themes in the feminist literature. In addition to coming to grips with the literature, each student will write a term paper on a topic of special interest. In the first 12 seminars discussion will center on the following topics: • Power, discourse, and subjectivity • Feminists reading Foucault • Space, place, and gender • Situated knowledge • Themes in feminist geography • Representing others • Politics Discussion each week will focus on a set of readings, which everyone will have read carefully. One or two students will lead the discussion for each article; this involves providing a brief summary of the argument and a critical assessment of it as well as some questions for discussion. We’ll have space on Blackboard for posting your notes on articles before class. We’ll try to vary the discussion protocol so class doesn’t get too boring. In the final weeks of the semester, we’ll focus on student papers, which will include a mock AAG session (presentations of your papers). One week before your presentation you will need to distribute your paper to the class; each of you will also act as discussant for another student’s paper. You’ll receive feedback from your presentation, from your discussant, and from me and then have the chance to revise your paper accordingly. Evaluation will be based on class participation, your oral presentation, and the term paper. 1 My official office hours are Mon & Tues 2-3:30, but I’m happy to meet with you at other times as well. -

Intersectional Feminist and Queer Geographies: a View from ‘Down-Under’

Intersectional feminist and queer geographies: A view from ‘down-under’ Lynda Johnston* Geography Programme Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 Aotearoa New Zealand +64 7 838 4466 x 9172 [email protected] Intersectional feminist and queer geographies: A view from ‘down-under’ Abstract Despite rapid growth of geographies of genders and sexualities over the past decade, there is still a great deal of homophobia, transphobia, and heterosexism within academic knowledges. A queer and feminist intersectional approach is one way to highlight gendered absences, institutionalized homophobia and transphobia. To understand the diversity of genders and sexualities, feminist and queer geographers must continue to talk about, for example, genders (beyond binaries), sex, sexualities, bodies, ethnicities, indigeneity, race, power, spaces and places. It is vitally important to understand the way that genders and sexualities intermingle in community group spaces, rural spaces, and within indigenous spaces in order to push the boundaries of what feminist and queer geographers understand to be relevant sites of queer intersectionality. Reflecting on the production of queer and feminist geographical knowledges ‘down-under’ may prompt others to consider the way place matters to intersectional feminist and queer geographies. Keywords: feminist; genders; indigeneity; intersectionality; queer; sexualities Introduction For many years I have been heavily involved in organising queer events for my region’s - Hamilton in Aotearoa New Zealand - rainbow communities. This means working with and for communities with diverse genders, sexualities, and ethnicities. Most significant, however, was (and still is) the imperative of this work to acknowledge the indigenous politics of Māori sovereignty, or tino rangatiratanga of indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand.