Road to Independence April 1775-July 1776

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Richatd Henry Lee 0Az-1Ts4l Although He Is Not Considered the Father of Our Country, Richard Henry Lee in Many Respects Was a Chief Architect of It

rl Name Class Date , BTocRAPHY Acrtvrry 2 Richatd Henry Lee 0az-1ts4l Although he is not considered the father of our country, Richard Henry Lee in many respects was a chief architect of it. As a member of the Continental Congress, Lee introduced a resolution stating that "These United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States." Lee's resolution led the Congress to commission the Declaration of Independence and forever shaped U.S. history. Lee was born to a wealthy family in Virginia and educated at one of the finest schools in England. Following his return to America, Lee served as a justice of the peace for Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1757. The following year, he entered Virginia's House of Burgesses. Richard Henry Lee For much of that time, however, Lee was a quiet and almost indifferent member of political connections with Britain be Virginia's state legislature. That changed "totaIIy dissolved." The second called in 1765, when Lee joined Patrick Henry for creating ties with foreign countries. in a spirited debate opposing the Stamp The third resolution called for forming a c Act. Lee also spoke out against the confederation of American colonies. John .o c Townshend Acts and worked establish o to Adams, a deiegate from Massachusetts, o- E committees of correspondence that seconded Lee's resolution. A Declaration o U supported cooperation between American of Independence was quickly drafted. =3 colonies. 6 Loyalty to Uirginia An Active Patriot Despite his support for the o colonies' F When tensions with Britain increased, separation from Britain, Lee cautioned ! o the colonies organized the Continental against a strong national government. -

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Approved in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic June 14, 2016 During the Forty-sixth Ordinary Period of Sessions of the OAS General Assembly AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES Organization of American States General Secretariat Secretariat of Access to Rights and Equity Department of Social Inclusion 1889 F Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 | USA 1 (202) 370 5000 www.oas.org ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 More rights for more people OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Organization of American States. General Assembly. Regular Session. (46th : 2016 : Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) : (Adopted at the thirds plenary session, held on June 15, 2016). p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.P) ; (OAS. Official records ; OEA/ Ser.D) ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 1. American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2016). 2. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--America. 3. Indigenous peoples--Legal status, laws, etc.--America. I. Organization of American States. Secretariat for Access to Rights and Equity. Department of Social Inclusion. II. Title. III. Series. OEA/Ser.P AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) OEA/Ser.D/XXVI.19 AG/RES. 2888 (XLVI-O/16) AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES (Adopted at the third plenary session, held on June 15, 2016) THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, RECALLING the contents of resolution AG/RES. 2867 (XLIV-O/14), “Draft American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” as well as all previous resolutions on this issue; RECALLING ALSO the declaration “Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas” [AG/DEC. -

Chapter 4-5: Study Focus • Essay Format Essential Questions 9

Chapter 4-5: Study Focus • Essay Format Essential Questions 9. What were The Coercive Acts of 19. What were the central 1774 (the Intolerable Acts) and why ideas and grievances expressed Content Standard 1: The student were they implemented? will analyze the foundations of in the Declaration of Indepen- dence? the United States by examining 10. Why was the First Continental the causes, events, and ideolo- Congress formed? gies which led to the American 20. How did John Locke‛s the- Revolution. ory of natural rights infl uence 11. What happened at the Battles of the Declaration of Indepen- Lexington and Concord and what was dence? 1. What were the political and eco- the impact on colonial resistance? nomic consequences of the French and Indian War on the 13 colo- 21. What is the concept of the 12. What was the purpose of Patrick social contract? nies? Henry‛s Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death speech? 2. What were the British imperial 22. What are the main ideals policies of requiring the colonies to 13. What was the purpose of and established in the Declaration pay a share of the costs of defend- main arguments made by Thomas of Independence? ing the British Empire? Paine‛s pamphlet Common Sense? 23. What were the contribu- 3. What the Albany Plan of Union? 14. What were the points of views tions of Thomas Jefferson of the Patriots and the Loyalists and the Committee of Five in 4. What was the signifi cance of the about independence? drafting the Declaration of Proclamation of 1763? Independence. -

Brexit and Jersey

BREXIT AND JERSEY Mark Boleat April 2016 Executive summary On June 23rd voters in the United Kingdom will decide whether the UK should remain a member of the European Union. The decision will be of massive importance to the UK, a “leave” vote being followed by years of uncertainty as Britain seeks to establish a new economic relationship not just with the European Union but also with the rest of the world. By extension, the vote will also be of crucial importance to Jersey, given that Jersey’s economy is closely tied to that of the UK and Jersey’s prosperity depends on it being semi- detached to the UK. When Britain decided to seek to join the then EEC in 1971 this was seen as potentially very damaging to Jersey, at the least resulting in increased competition for agricultural products, and at worst threatening the tourism and finance industries if Jersey were to be subject to the full rules of the EEC. In the event Jersey got the best possible deal - inside the common external tariff but outside the EEC generally. These arrangements were set out in Protocol 3 to the 1972 Accession Treaty. In practice, Jersey became loosely attached to the EEC as well as semi-detached to the UK. This was achieved through low- key way, but with good preparation in both Jersey and the UK. The Brexit debate in the UK is as much emotional as rational. Business is strongly in favour of Britain remaining in the EU but finds it difficult to engage in such a debate. -

AMERICAN REVOLUTIONREVOLUTION Thethe Enlightenmentenlightenment Thethe Ageage Ofof Reasonreason

AMERICANAMERICAN REVOLUTIONREVOLUTION TheThe EnlightenmentEnlightenment TheThe AgeAge ofof ReasonReason ▶ 1650-1800 ▶ Laws of Nature applied to society ▶ Rationalism . “Dare to know! Have the courage to use your own reason!” – Immanuel Kant ▶ Liberalism ▶ Deism . “The Clockmaker” . Absent of human affairs TheThe EnlightenmentEnlightenment JohnJohn LockeLocke ▶ Second Treatise on Government . “The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind … that, being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions” . “Men being, as has been said, by nature, all free, equal, and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.” . “Whensoever therefore the legislative shall transgress this fundamental rule of society; and either by ambition, fear, folly or corruption, endeavour to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people; by this breach of trust they forfeit the power the people had put into their hands for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the people, who have a right to resume their original liberty, and, by the establishment of a new legislative, (such as they shall think fit) provide for their own safety and security, which is the end for which they are in society.” TheThe EnlightenmentEnlightenment AdamAdam SmithSmith ▶ An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations ▶ Laissez-faire . Free trade ▶ “the invisible hand” ▶ Three Laws . More production from self- interest . -

Delaware: Allan Mclane

Delaware: Allan McLane Born in Philadelphia, PA on August 8, 1746, Allan McLane was one of George Washington’s boldest soldiers, but most reluctant U.S. marshals. By the time the American Revolution began, McLane had moved to Delaware, where he had a trading business, and immediately enlisted as a lieutenant in Caesar Rodney's Delaware Regiment. McLane’s company numbered about one hundred men, and included some Oneida Indian scouts. So devoted was he to his troops, that McLane used much of his inherited fortune for their pay and equipment. McLane participated in Washington’s disastrous New York Campaign of 1776.109 During this military campaign and the Battle of Princeton in January 1777, McLane earned a promotion to captain and began a legendary career as a cavalryman and spy.110 McLane utilized different disguises to infiltrate British camps and gather vital information that contributed to the success of American forces at the battles of Monmouth Courthouse (June 28, 1778) and Stoney Point (July 16, 1779).111 On another occasion, a wounded McLane personally killed two British soldiers and escaped capture, despite being abandoned by his three companions. Collectively, McLane’s courage and daring personality helped him earn the rank of colonel by the end of the war in 1783.112 Portrait of Allan McLane. Courtesy of the State of Delaware Office of Historical and Cultural Affairs 109 He was also one of the first offices to question Benedict Arnold’s loyalty. 110 “History - The First Generation of United States Marshals/The First Marshal of Delaware: Allan McLane,” U.S. -

The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 17th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 13th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Myrice, Erin, "The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa" (2015). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2015/004/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice 2 “An African poet, Taban Lo Liyong, once said that Africans have three white men to thank for their political freedom and independence: Nietzsche, Hitler, and Marx.” 1 Marx raised awareness of oppressed peoples around the world, while also creating the idea of economic exploitation of living human beings. Nietzsche created the idea of a superman and a master race. Hitler attempted to implement Nietzsche’s ideas into Germany with an ultimate goal of reaching the whole world. Hitler’s attempted implementation of his version of a ‘master race’ led to one of the most bloody, horrific, and destructive wars the world has ever encountered. While this statement by Liyong was bold, it held truth. The Second World War was a catalyst for African political freedom and independence. -

Delaware in the American Revolution (2002)

Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House Washington, D. C. October 12, 2002 - May 3, 2003 HIS catalogue has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition, Delaware in the American Revolution , on display from October 12, 2002, to May 3, 2003, at Anderson House, THeadquarters, Library and Museum of the Society of the Cincinnati, 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, D. C. 20008. It is the sixth in a series of exhibitions focusing on the contributions to the American Revolution made by the original 13 he season loudly calls for the greatest efforts of every states and the French alliance. Tfriend to his Country. Generous support for this exhibition was provided by the — George Washington, Wilmington, to Caesar Rodney, Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati. August 31, 1777, calling for the assistance of the Delaware militia in rebuffing the British advance to Philadelphia. Collections of the Historical Society of Delaware Also available: Massachusetts in the American Revolution: “Let It Begin Here” (1997) New York in the American Revolution (1998) New Jersey in the American Revolution (1999) Rhode Island in the American Revolution (2000) Connecticut in the American Revolution (2001) Text by Ellen McCallister Clark and Emily L. Schulz. Front cover: Domenick D’Andrea. “The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776.” [detail] Courtesy of the National Guard Bureau. See page 11. ©2002 by The Society of the Cincinnati. -

Section 7-1: the Revolution Begins

Name: Date: Chapter 7 Study Guide Section 7-1: The Revolution Begins Fill in the blanks: 1. The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from various colonies in September of 1774 to discuss the ongoing crisis with Britain. 2. The Minutemen were members of the Massachusetts militia that were considered ready to fight at a moment’s notice. 3. General Thomas Gage was the British military governor of Massachusetts, and ordered the seizure of the militia’s weapons, ammunition, and supplies at Concord. 4. The towns of Lexington and Concord saw the first fighting of the American Revolution. 5. The “Shot heard ‘round the world” was the nickname given to the first shot of the American Revolution. 6. Americans (and others) referred to British soldiers as Redcoats because of their brightly colored uniforms. 7. At the Second Continental Congress, colonial delegates voted to send the Olive Branch Petition to King George III and created an army led by George Washington. 8. The Continental Congress created the Continental Army to defend the colonies against British aggression. 9. George Washington took command of this army at the request of the Continental Congress. 10. The Continental Congress chose to send the Olive Branch Petition to King George III and Parliament, reiterating their desire for a peaceful resolution to the crisis. 11. Siege is a military term that means to surround a city or fortress with the goal of forcing the inhabitants to surrender due to a lack of supplies. 12. Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allan captured Fort Ticonderoga in New York, allowing George Washington to obtain much needed supplies and weapons. -

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders By around 410AD, the last of the Romans had left Britain to go back to Rome and England was left to look after itself for the first time in about 400 years. Emperor Honorius told the people to fight the Picts, Scots and Saxons who were attacking them, but the Brits were not good fighters. The Scots, who came from Ireland, invaded and took land in Scotland. The Scots split Scotland into 4 separate places that were named Dal Riata, Pictland, Strathclyde and Bernicia. The Picts (the people already living in Scotland) and the Scots were always trying to get into England. It was hard for the people in England to fight them off without help from the Romans. The Picts and Scots are said to have jumped over Hadrian’s Wall, killing everyone in their way. The British king found it hard to get his men to stop the Picts and Scots. He was worried they would take over in England because they were excellent fighters. Then he had an idea how he could keep the Picts and Scots out. He asked two brothers called Hengest and Horsa from Jutland to come and fight for him and keep England safe from the Picts and Scots. Hengest and Horsa did help to keep the Picts and Scots out, but they liked England and they wanted to stay. They knew that the people in England were not strong fighters so they would be easy to beat. Hengest and Horsa brought more men to fight for England and over time they won. -

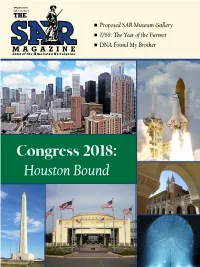

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them.